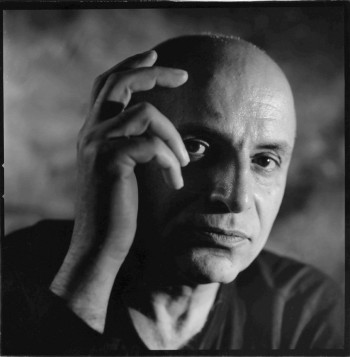

Paul Motian: 1931-2011

Photo by Robert Lewis.

He showed us new ways to think about jazz drumming. There will never be another like him.

by Michael Parillo

On a dark night at the Village Vanguard, the audience snakes slowly down the long staircase and settles in at tiny tables, squeezed together nice and tight. In such close quarters, strangers exchange greetings, knees bumping. Soon the house lights go down and the stage lights come up, the back curtain casting a lush red glow on the Gretsch kit out front. Along with his bandmates for the week, Paul Motian—bald with tinted glasses, lithe, stylish, cool—weaves his way from the green room through the cheering crowd, with all eyes on him, and eventually reaches the stage. As the applause dies down, a hushed sense of anticipation takes its place. The Motian veterans in the house practically feel uneasy. What’s going to happen? What will it sound like tonight? No one knows.

With the occasional shoveling of ice by the bartender in the back now providing the only sound in the room, Motian picks up his sticks and glances at his comrades. Then he extends his right arm, and—clang!—he hits a cymbal, once, with authority, shattering the silence. Starting to create a loosely knit web of rhythm, he plays a brief, wide-open roll on the snare and brings the hi-hats together a few times with his left foot. The nervous energy at the tables deflates a bit; the magic is beginning. The other players join in, and they’re off. The spell won’t be broken for around seventy-five minutes, when the band takes a bow. Advertisement

Great drummers play at the venerable Vanguard every month, but in recent years the shabby-chic basement room was Motian’s turf. Starting in the mid-2000s, Motian, who passed away this past November 22 at age eighty, figured out a way to maintain a productive career without leaving Manhattan, and the Vanguard was the venue that hosted him and his varied groups most often. The drummer and composer made serious music, but the little club on Seventh Avenue South was his playground for fifty years.

BEGINNINGS

Stephen Paul Motian was born in Philadelphia on March 25, 1931, to Armenian parents and grew up in Providence, Rhode Island. In a 2005 MD interview with Burt Korall, Paul offered insight into the Middle Eastern–sounding themes in many of his compositions by saying, “As a kid, Arabic- and Turkish-derived melodies and rhythms got me dancing around the parlor.”

Taking up the drums in earnest around age twelve after a brief fling with the guitar, Motian found his life’s work. After high school, he played in the U.S. Navy band; he was stationed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1953 and ’54, studying with the famed Radio City Music Hall percussionist Billy Gladstone, among other teachers. Bebop pioneer Kenny Clarke, whom Motian often credited with inspiring his wonderfully sensitive brush playing, was a major influence around this time, as was Max Roach. Once Motian got out of the service he moved to Manhattan’s East Village. Advertisement

Just as jazz was really blossoming in the ’50s, so too was Motian’s drumming, as Paul played tirelessly and made his first significant recordings in the middle of the decade. He gigged briefly with pianist Thelonious Monk, whose tunes he would later cover frequently—and whose angular presence seems to lurk in the background of some of his own compositions. And then he joined forces with pianist Bill Evans.

Evans’ groundbreaking trio, which also featured bassist Scott LaFaro, remains one of the most heralded units in jazz history. Rather than supporting Evans as subordinates, Motian and LaFaro blended with the pianist as equals, nurturing a fresh style that was rooted in tradition but branched out into new modes of improvisational interplay. Motian said his favorite album with this group was Portrait in Jazz, a studio session released in 1960, which he preferred to the more famous—and more understated—live recording from 1961, Sunday at the Village Vanguard. (A second album from the same June 25 date at the Vanguard, Waltz for Debby, was released in 1961, and a three-CD box set, The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings, 1961, was issued in 2005.) Tragically, LaFaro was gone mere days after the legendary performance, killed in a car accident on July 6, 1961, at just twenty-five. Motian remained with Evans until 1964, when he quit and went home in the middle of a tour. By then, Paul told MD in 2005, “We played so softly, we were hardly moving.”

“That original trio made such an indelible mark on the jazz world and trio culture,” says bassist Eddie Gomez, who played with Evans for eleven years starting in 1966 and joins Motian and keyboardist Chick Corea on the new double-disc Evans tribute Further Explorations, which was recorded over two weeks in May 2010 at the Blue Note in Manhattan. “Bill chose the musicians for the kind of interactive play that Scott and Paul developed. Scott and Paul were very contemporary in the sense that they were looking to expand the music back then, in the ’60s. Miles’s band was exploring that too, in a different way, with Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter. Those bands were opening up the language of trio playing.” Advertisement

In the mid-’60s Motian worked with pianists Paul and Carla Bley and with saxophonist Albert Ayler, before joining another far-reaching trio, this time with pianist Keith Jarrett, who was just bursting onto the scene, and bassist Charlie Haden, who’d been in saxophonist Ornette Coleman’s band. This group made many recordings, including Jarrett’s debut as a leader, Life Between the Exit Signs (1967). Motian pointed to Jarrett’s The Survivors’ Suite (1976), which augmented the trio with saxman Dewey Redman, as his favorite album by the unit. Starting in the late ’60s, Motian and Jarrett also spent time in sax/flute player Charles Lloyd’s group. And Paul famously backed Arlo Guthrie at Woodstock in 1969.

As the ’70s dawned, the always feisty drummer took up a new challenge and began his parallel career as a composer and bandleader.

BRANCHING OUT

Motian did his writing on the piano—and his first set of keys was most likely a charmed one, as he bought it from Keith Jarrett. Motian’s 1972 debut as a leader, Conception Vessel, kicked off a fruitful, albeit interrupted, association with the ECM label and features Jarrett and Haden, plus Becky Friend on flute, Leroy Jenkins on violin, and Sam Brown on guitar. Notice the presence of the guitar, an instrument that would continue to take on heavy significance in Motian’s musical endeavors.

For his 1982 release, Psalm, Motian was joined by Ed Schuller on bass and Billy Drewes on sax, plus two men around twenty years his junior who would be counted among his very closest musical accomplices for the rest of his life: saxophonist Joe Lovano and guitarist Bill Frisell. “I was a huge fan of Paul’s,” Frisell says. “The day he first called me, it was a complete surprise that he would ask me to come over and play. I had his Conception Vessel album sitting there facing me on the floor, and the phone rings and he says, ‘Hi, this is Paul Motian….’ I just about had a heart attack. We played together ever since. It’s just gigantic, the importance of him in my life—even if I hadn’t played with him.” Advertisement

For a drummer who made a habit of flouting expectations, Motian was perhaps at his most unpredictable with Frisell and Lovano. The trio’s recorded output runs the gamut from beautiful ballads to dreamy cloud-watching soundscapes to flaming barn burners, all heightened by sharp listening and a unified sense of melody among the bandmates—as well as by a rare ability to ditch the past and live in the moment.

“Paul made me feel like I was discovering everything I was playing for the first time,” Frisell says. “He was allowing me to be myself, and I could just go full force, as far as my imagination could go. I credit him with giving me the confidence and the experience of really finding my own voice.

“I’m playing with him and I think, Wow, I just had this great idea,” Frisell continues, “but then I realize later that there was a lot of telepathy stuff going on, almost like he was transmitting his ideas into me. Like we’d be on a train somewhere, and I would be singing some song in my head that we had played the night before, and then he would start singing it right at the exact same moment, at the same point, in the same key. You just get into a zone of being connected in this amazing way.” Advertisement

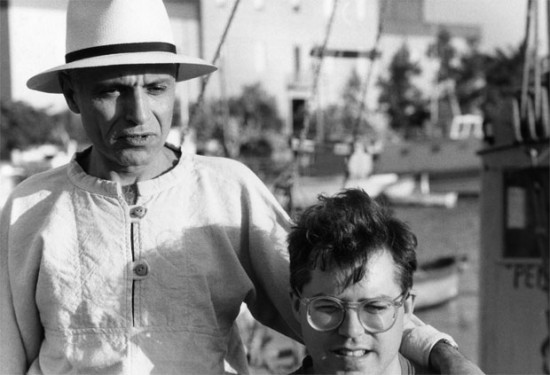

Motian and Bill Frisell in Cagliari, Italy, July 1986. Photo by Agostino Mela.

The Motian/Frisell/Lovano trio played all over the world, always coming home to the Vanguard for at least a couple of weeks a year. Its discography, sometimes with special guests, includes Monk in Motian (1988), three volumes of On Broadway (1989, 1993), Motian in Tokyo (1991), Trioism (1994), At the Village Vanguard (1995), I Have the Room Above Her (2005), and Time and Time Again (2007).

DEEPER AND DEEPER

By the ’90s Motian had enjoyed a long career and was already something of an elder statesman, even if the word elder never quite fit him. He was free to mix in his pieces with time-honored standards that could either be deconstructed or served straight up—whatever he felt at that moment. “I’m into me now,” he told Ken Micallef in a 1994 MD interview, after being told that he sounds like no one else. “That’s what I play. I don’t give a shit if it’s this or that or whatever. I’m just playing from what I’m hearing and turning myself on and getting myself from myself!” Motian laughed, but it’s clear he wasn’t joking.

As for the drummer’s compositions, Frisell says, “He would sometimes write very specific harmony—real dense, unusual harmonies—but there were also ones that were super-open, where I could make up my own stuff. Some songs are maybe just a major scale, and then others are sort of odd, chromatic, ‘puzzle’ things. There was a lot of variety in the stuff he wrote, and it always sounded like him somehow.” Advertisement

Motian performed with so many combos in his last two decades that it’s hard to make sense of it all. In 1993 he released Paul Motian & the Electric Bebop Band, an album of standards featuring two guitarists, Kurt Rosenwinkel and Brad Shepik. In the lineage of packs of young lions led by big-cat drummers, which includes Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and Elvin Jones’s Jazz Machine, the Electric Bebop Band was something of a training camp for emerging musicians with a searching soul (although in this case the leader was neither the largest member of the pride nor the one with the biggest mane). In recent years the group changed its name to the Paul Motian Band. Its very fine last album, the stylistically and dynamically varied 2006 set Garden of Eden, features Chris Cheek and Tony Malaby on sax, Jerome Harris on bass, and Ben Monder, Steve Cardenas, and Jakob Bro on guitar.

Fittingly, much of Motian’s last great work was done in trios, and his final week of gigs, in September 2011, was at the Vanguard with saxophonist Greg Osby and pianist Masabumi Kikuchi. Paul’s 2010 album, Lost in a Dream, which earned a perfect five stars from Modern Drummer, finds the drummer on stage—at the Vanguard, of course—with pianist Jason Moran and saxophonist Chris Potter, playing mostly ballads. And this year’s aforementioned Further Explorations, with Chick Corea and Eddie Gomez, is the ideal document of late-era Motian accompaniment.

“Paul had an almost orchestral-percussion-section sound,” Gomez says. “And his sound is his. It’s like composing all the time, the way he plays—and it’s also improvised. I’ve always loved approaching music so that it breathes and has the components that make it sing, dance, and touch your heart. And Paul has all that. He makes the music just kind of vibrate. He’s very subtle, and he also has all that energy and swing that you want.” Further Explorations’ opening number, Bill Evans’ “Peri’s Scope” (first heard on Portrait in Jazz), offers a prime example of Motian’s straight-ahead swinging, with a crisp hi-hat shuffle and singing ride cymbal work, plus crafty little solo breaks. Advertisement

Speaking of soloing, like everything else Motian did it his way. He sometimes mentioned a dislike of drum solos, yet it wasn’t as if his arm needed to be twisted to get him to play a few choruses by himself. Besides, he was so skilled and creative—not to mention so musical, keeping the form and melody alive—that he always found something compelling to say during his brief showcases. Listen to the Lost in a Dream reading of his haunting tune “Abacus.” After the sax and piano take turns stating the melody, Motian downshifts into a solo. He takes his time developing his ideas, as always, slowly building on his own minimal foundation. He begins with a cymbal, some bass drum, and a bit of hi-hat, and starts adding his throaty snare and rumbling, deep-voiced toms, getting contrast by playing on the rims as well. Over the course of around three minutes, he allows his sound to grow until he’s whipping up a frenzy, like a storm starting far off at sea and building force as it crashes to shore. Just at the high point, he hits a resounding accent, and his mates reenter for one last triumphant pass through the melody, with Motian still rolling and tumbling around the kit. It’s a deep, spine-tingling solo that tells a story—in the way that only Motian’s drums can.

HONORING THE MUSE

Motian often talked about being an accidentalist, saying he just let things happen in the music, without discussion or forethought. “He was always on the edge,” Bill Frisell says. “I think that’s why we were able to play so long and it always felt new. He never settled into a safe zone—he was always reaching for something he’d never played before.”

Part of the reason why Motian was so successful at subverting expectations and demolishing any clichéd concept of what “the jazz drummer” should be is because he had a firm grasp of tradition; he possessed the ability to follow any rule that he might also gleefully break. Paul could come at you with a style that challenged your idea of traditional timekeeping, but it’s equally true that he could lay it down simply and solidly with the best of ’em. He often blended both approaches within a piece, showing that traditional and avant-garde jazz simply represent points along a continuum. Advertisement

“Some people say he didn’t play time, or something,” Frisell says. “That’s absurd. He had the deepest beat of anyone I ever played with. Some of the stuff I read about him, they talk about how he’s ‘abstract,’ or this or that, but they miss that he did play with Oscar Pettiford and Coleman Hawkins. That’s all in there. I think they have to listen a little harder.”

“I think Paul is one of the grand artists of the twentieth century, certainly on the instrument,” Eddie Gomez says. “But I don’t know that he gets enough credit. I think his art makes him less accessible to others. If you only like to hear a kind of playing that’s driven either by technique or by certain stylistic ways, Paul isn’t going to come up on your radar, because he’s so understated and artistic and special. He heard music in a different way and opened up all kinds of possibilities.”

Motian would probably just blow off the subject of “in” versus “out,” straight up versus abstract, with a wave of his hand. “I believe that ‘time’ is always there,” he told Scott Kevin Fish in a 1980 MD interview. “I don’t mean a particular pulse, but the time itself. It’s like a huge sign that’s up there and it says time. It’s there and you can play all around it.”

Advertisement

THE MAN HIMSELF

“Paul was a lot of fun to be around,” Gomez says of his weeks spent with Motian at the Blue Note playing the Bill Evans–inspired material that comprises Further Explorations. “Honestly I had no idea he was ill. He seemed so perfectly healthy and full of life, and he played that way. We got a chance to hang out and kid around a lot and talk about older times. He was a great spirit.”

After spending thirty-plus years making music with Motian, Frisell offers rare insight into a man who could seem a bit prickly to the outside world but who also often wore a wide smile. “He was protective of his own space,” the guitarist says. “He lived alone, and his whole life was about music. He just wanted to stay in the music, I think. He was super-sensitive, and sometimes people like that have to put up a little bit of a barrier, just to keep themselves from getting trampled on. But he was so generous with people too, and if he let you in, he really let you in.”

When Frisell is asked about Motian’s sense of humor, he responds, “Paul had this real intense thing, but I was looking at a bunch of old pictures, and there are millions of ’em where he’s just laughing and laughing. He always tried to lift things up. He wouldn’t stay down in some dark place for long. He had that effect on people, and certainly on the music. It was very serious and it was never a joke, but there was joy in it.” Advertisement

This piece originally ran in the May 2012 issue of Modern Drummer magazine, which is available as a back issue or on the Apple iTunes Store.