Steve Hackett Re-Revisits Genesis

The bandleader and longtime guitarist with the legendary British band discusses the great drummers he’s played with, as well as his latest release, Genesis Revisited II.

The bandleader and longtime guitarist with the legendary British band discusses the great drummers he’s played with, as well as his latest release, Genesis Revisited II.

MD: It’s amazing how Phil Collins was able to make all of the odd-time rhythmic stuff work in Genesis. How did he do that?

Steve: I don’t know how, because at times I think the [music] didn’t always swing. Sometimes half of the band is going its own sweet way and the rhythm section is doing something else entirely. In the latter-day progressive world, people often think you have to have a tricky time signature from the word go, but we really just fell into those things. I often think too much punctuation and not enough statement can get in the way of [songwriting]. I don’t think everything works [in Genesis’s music], but I’d say a good 80 percent of it stands the test of time.

MD: John Shearer’s playing is reminiscent of Phil Collins’, particularly on a song like “Clocks—the Angel of Mons” from your 1979 solo record, Spectral Mornings. What’s your take on Shearer’s drumming?

Steve: I loved working with John, and he was immensely popular with audiences. He was a tremendous showman. We recorded the solo at the end of “Clocks” within a large studio facility in Holland [Phonogram Studios in Hilversum], and I think we had every mic in the place going on there. We used to call the drum sound “elephants,” because if you got anywhere near the kit you felt as if you were being trampled by elephants, because he had a double bass set in those days. Really, he was the first full-time drummer I was working with for my solo stuff. I was very proud of that early band and the album we made, Spectral Mornings. It was a great thrill for me to walk out of Genesis into an era of potential insecurity and be able to work with great players like that. Advertisement

MD: Were you present for the drum tracking for Genesis Revisited II?

Steve: I wasn’t able to do that, because I was wearing a lot of hats in order to bring this thing in on time. I often think that with drummers it’s best to stay out of the way. That doesn’t mean I’m uninterested in what they do, but I don’t understand enough about the drummer’s craft to possibly be able to say, “Do this.” I don’t know anyone who’s a nondrummer who can choreograph drums. I had this conversation with Bill Bruford many years ago when I worked with Evelyn Glennie and I was required to write an hour’s worth of music for her. Bill said, “There’s no point writing a drum solo. You just can’t.” Bill was proven right. It was a lot of improvised stuff. So, an hour’s worth of music ended up being written on the back of an envelope. If you write a part for a drummer, you do so at your peril.

MD: For your album Highly Strung, you worked with Ian Mosley, prior to his joining Marillion.

Steve: Ian is a phenomenal drummer; phenomenally fast.

MD: As a member of Marillion Ian doesn’t so much blow you away as impress you with his economy of beats. Would you agree?

Steve: That’s true. Funnily enough, Marillion has a really interesting new album at the moment [Sounds That Can’t Be Made], and the playing is very clever rhythmically, especially the first track [“Gaza”]. I think he’s become a more economical player within the context of that band. But he’s done some seriously fast licks. There’s a track we did together on Highly Strung called “Always Somewhere Else.” The drums are in a fast 7/8 and every bit the equal to Phil Collins’ economy on that one. I seem to recall it was recorded in a room that had metallic walls. God knows how [Mosley] managed to keep time in there, because the sound must have been deafening. It was a studio in London called Marcus [Marcus Music & Redan Recorders].

Steve: That’s true. Funnily enough, Marillion has a really interesting new album at the moment [Sounds That Can’t Be Made], and the playing is very clever rhythmically, especially the first track [“Gaza”]. I think he’s become a more economical player within the context of that band. But he’s done some seriously fast licks. There’s a track we did together on Highly Strung called “Always Somewhere Else.” The drums are in a fast 7/8 and every bit the equal to Phil Collins’ economy on that one. I seem to recall it was recorded in a room that had metallic walls. God knows how [Mosley] managed to keep time in there, because the sound must have been deafening. It was a studio in London called Marcus [Marcus Music & Redan Recorders].

MD: A few years ago Simon Phillips [Pete Townshend, Toto] said he was cutting tracks with you and Chris Squire of Yes. Did you end up using that material?

Steve: I didn’t get to work with Simon as much as I would have liked to. That got lost in the politics. Sometimes these things go that way. But Simon is on my record Beyond the Shrouded Horizon, and he played wonderfully on it. Chris is on it as well, and you get an idea of what that trio would have sounded like. Advertisement

MD: You used rhythmic programming for your 1981 solo record, Cured. Did you make this decision based on budgetary concerns?

Steve: You’re absolutely right. Strangely enough, I had this same conversation with Bill Bruford around that same time. We each had bands, and even though we were a success on paper, in the bank we were in the red. Suddenly, the Linn [drum computer] seemed like a short-term answer to an awful lot of financial problems. But I still believe that to play with a virtuoso drummer is the ideal situation. Out of the fifty or so albums I’ve done, that’s the one I say “Ouch!” when I look back on it. Not that the record isn’t interesting in other ways, but in terms of production techniques, I have warmed to that record the least.

MD: A few different drummers make appearances on Genesis Revisited II. Will you be touring with more than one drummer?

Steve: That was suggested, but we’re doing it with one, Gary O’Toole. During my time with Genesis, of course, having two drummers became part of the approach. In the 1971-through-1975 period, and on record, it was always one drummer and percussion tracked up. Gary is a phenomenal drummer in his own right, and I’m working with the team I’ve got—Lee Pomeroy on bass, Nad Sylvan on vocal, Amanda Lehmann on guitar and vocals, Roger King on keyboard, and Rob Townsend on all things blown and percussion. It’ll be me on guitar trying to avoid vocals, so that I can concentrate on those difficult guitar parts.

Will Romano

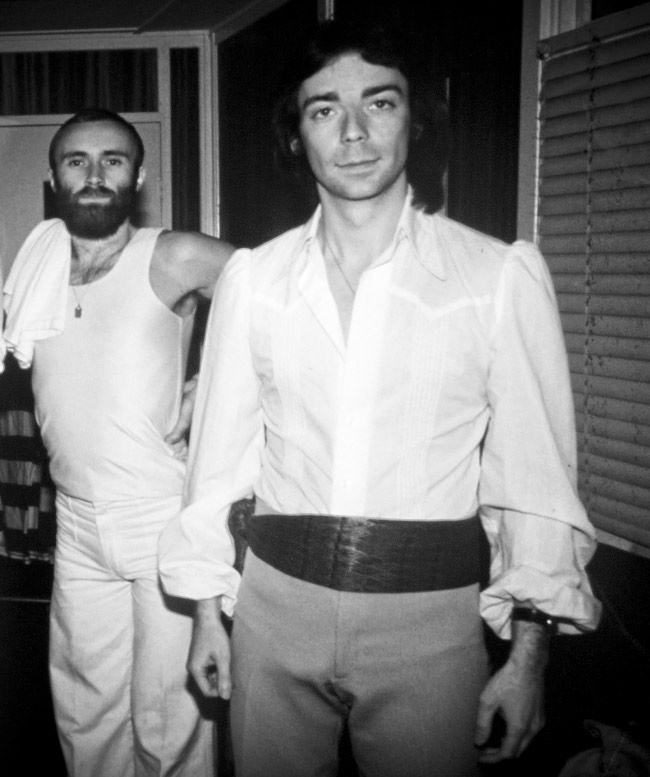

Photo of Phil Collins and Steve Hackett in 1977 by Armando Gallo. To read more with Steve Hackett, check out the April 2013 issue of Modern Drummer magazine here. Modern Drummer is also available on iTunes/iOS and Android/Amazon. Advertisement