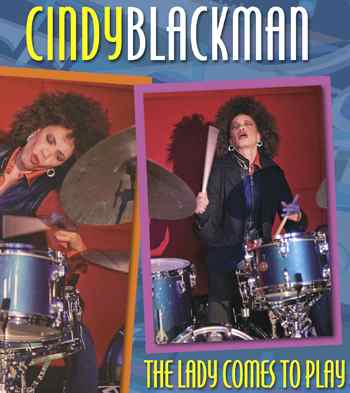

Cindy Blackman: The Lady Comes To Play

by Ken Micallef

Last year, drumming dynamo Cindy Blackman left behind her big-ticket rock gig with Lenny Kravitz to unleash the jazz devil inside. Her drumming prowess is simply astounding–and is now finally on full display.

Serial jazz and rock drum killer Cindy Blackman is the kind of ultra-talented, well-trained, and dynamically inspired musician who could only exist in the new millennium. Her tenth, double CD, Music For The New Millennium, shows a creative force to be reckoned with, revealed in the album’s amalgam of late-’60s Miles Davis–inspired compositions (in classic quartet format) fired by drumming that could fairly be described as jazz toxic shock therapy.

Undaunted by pedigree, gender, or era, Blackman takes on a challenge many drummers have taken on but few have risen to. Describing her hero Tony Williams as “the technology of the drumming world,” she goes about making his innovations her own. Blackman makes no bones about her total fascination and admiration for the heroic figure who not only inspired some of Miles Davis’s greatest recordings but who practically invented jazz-rock (i.e., fusion) with his 1969 album, Emergency! Her drumming reflects everything (and every era) that Tony Williams had to offer. Advertisement

Performing recently with her crack quartet at New York’s Jazz Standard, Blackman came on like a whirlwind, driving her group’s atmospheric treatments with fulminating flam combinations, outrageous single stroke–roll meltdowns, and full-set phrases all within a boiling pulse. Never saying a word, Blackman looked fierce on her small Gretsch set, kicking her quartet with explosive drumming that left nothing to the imagination. Music For The New Millennium extends the music heard at the Jazz Standard, with Blackman coupling blast furnace drumming styles modeled on Believe It, Four & More, and Million Dollar Legs with an abstract melodic and compositional approach.

That Blackman would become a Tony Williams disciple wasn’t a sure thing when she was growing up in Hartford, Connecticut. Attracted to the instrument early on, she became active in the local Forestville Fife & Drum Corps at age eleven, studied at the nearby Hart School Of Music during high school, then enrolled at Berklee School Of Music, where she studied classical snare drum, harmony, and drumset (eventually with legendary instructor Alan Dawson). It was during her later high school years that Blackman was exposed to Tony Williams, an epiphany that inspires her to this day.

“When I first heard Tony on Miles Davis’ Four & More, I was trippin’,” she recalls from her Brooklyn apartment. “A friend who played it for me told me Tony was sixteen when he recorded it. He was my age and playing like that?! Then he put on Miles’ Live In Europe. I was completely hooked into Tony from that moment on.” Advertisement

Post Berklee, Blackman headed to New York in 1982 where she became a first-call player, working with Sam Rivers, Jackie McLean, Joe Henderson, George Benson, Wallace Roney, Patti LaBelle, and Rachel Z. Her first solo album, 1987’s Arcane, proved her talent went well beyond drumming. To expand her horizons further, Blackman donned an Afro wig and a fierce countenance for what was to become a fifteen-year association with Lenny Kravitz, joining the retro rocker’s band in the early ’90s. But her jazz allegiance never waned, as further albums Code Red, The Oracle, and Telepathy adhered to post-bop logic and terrific Tony stylings.

Cindy Blackman’s Brooklyn loft is evidence of someone who knows how to enjoy the finer things in life. A beautiful ’50s-era Gretsch round-badge Broadkaster set sits in one corner, across from an otherworldly looking, $100,000 high-tech sound system. Her good taste is evident in every aspect of the loft’s design, from Moroccan styled tile work to a multi-volume Miles Davis DVD collection. But Blackman’s drumming remains first and foremost in her consciousness, and every ounce of her being is focused on advancing her art. There’s no doubt about it, Cindy Blackman comes to play.

MD: Whether you’re playing rock or jazz, you always project a great sense of presence on the drums. You are there to play.

I once heard Ron Carter ask, “What do young musicians have to do other than play their instrument and be ready to play when they’re called upon”? I never forgot that. What else do you have to do but that? If you have something else to do, then maybe you’re in the wrong field. Advertisement

MD: How do you maintain that level of energy and exuberance? You sound like you’re ready to go full bore every time you sit at the drums.

Cindy: Just by loving what I do. I love playing the drums and playing music. When I think that I’m chasing the legends of Art Blakey, Tony Williams, and Elvin Jones, I’d better be ready. You better smack those drums, because those cats weren’t messing around. I’ve seen Art Blakey play and the whole stage shake. I’ve seen Elvin play with brushes and the snare drum popped off the stand. I’ve seen Tony play and everything bowled over like a big Mac truck.

MD: Is that insistence on laying it down missing in some younger players, or is it that they just didn’t get the chance to experience those masters?

Cindy: That is missing sometimes. There’s an urgency that drummers and musicians and people in the ’60s had, and it’s to do with what’s happening socially. In the ’60s when all those people that I mentioned had their incredible bands and playing situations, the times were very tumultuous. That lends itself to everyone having a certain kind of urgency when they play. The ’60s is my favorite period. The music was on edge and cutting. People knew they had to do individualized thinking and get away from the norm. And that was reflected in the music. I love that energy, and I think about that a lot. I tap into that.

Read the rest of this interview with Cindy Blackman in the June 2008 issue of Modern Drummer available at your favorite music store, bookstore, and newsstand in May 2008.