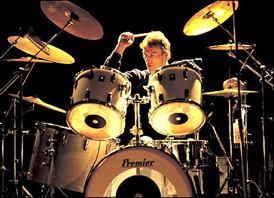

Rick Buckler

There have always been certain British rock bands who’ve been treated like deities at home, but who failed to translate to the American market. The Move, The Smiths, and The Wedding Present immediately come to mind. The Jam, who between 1977 and 1982 toured incessantly behind a series of hugely influential albums, certainly have to be considered near the top of that particular list.

There have always been certain British rock bands who’ve been treated like deities at home, but who failed to translate to the American market. The Move, The Smiths, and The Wedding Present immediately come to mind. The Jam, who between 1977 and 1982 toured incessantly behind a series of hugely influential albums, certainly have to be considered near the top of that particular list.

When singer/songwriter/guitarist Paul Weller expressed his desire end the group while they were at the apparent pinnacle of their critical and popular success, fans were dumbfounded–as, understandably, were bassist Bruce Foxton and drummer Rick Buckler. While Weller went on to a successful solo career–much less so in the States, it should be noted–Foxton and Buckler found it difficult to revisit their past glories, with Buckler eventually dropping out of professional music-making altogether. A couple years ago, however, the drummer returned to his great love, first with the live Jam-oriented band The Gift, and now with an outfit dubbed From The Jam, which, in addition to Foxton, features singer/guitarist Russell Hastings and multi-instrumentalist Dave Moore. MD jumped at the opportunity to chat with Rick Buckler during the band’s recent string of live dates.

How have the shows been going?

We’ve had some pretty good crowds and some pretty good reactions, which has been a pleasant surprise because it’s an unknown quantity after twenty-five years. The crowd is a mix of Jam fans who remember us from a long time ago, and people who are checking us out after having never seen us at all. It’s been great seeing the younger audiences.

Advertisement

What’s it like touring today as compared to the early days?

Back in the day we were under a lot more pressure to sell records and whatnot. So in a way it’s a lot more enjoyable.

Was it hard getting back on the horse, so to speak, when you got back into drumming a few years ago?

It was a bit of a struggle. I had to do three or four months of serious practicing to get myself back up to speed. It’s a little frustrating when you think, I want to do this drum roll, but your body just doesn’t want to know about it. [laughs] But it’s just about getting the old muscle memory back. Once I got over that period, it started turning into a lot more fun.

What were you most looking forward to about playing again?

One of the things I really wanted to do was revisit the Jam songs. When we did the last show in The UK in 1982, and we were going through the set, I remember thinking, This is probably the last time I’ll play these songs. So it was great having the opportunity to revisit them with The Gift, which was the band that sort of started this. I got together with Russell Hastings and Dave Moore in 2006 and did that for a year. Then we found ourselves on the same bill with Bruce on a couple occasions. He came up a do a couple numbers with us, and the reaction was fantastic. So we decided to put this on a more firm footing and go out and do it. We didn’t go out with the initial intent of re-forming the band; it just seemed to be the right thing to do at the right time.

Though The Jam were linked to the Mod revival in England, your records–and your drumming–were very diverse.

We did make a specific point during The Jam that we didn’t want to get stuck in any musical rut. I think that was where our second album came across some criticism. I think most people really expected In The City Part 2, and they didn’t get that. We changed for This Is The Modern World, which is very different from the first album. We were evolving as a band, exploring different things. We really felt for our own credibility that we should push the boundaries. Each of our albums took a different path.

Advertisement

Songs like “Funeral Pyre” and “Precious” have really interesting drum parts, not what you’d usually hear in a pop song.

If you’ve got a great song, you can really feed off of what it’s about. You find something in there that reflects that song, and rather than basing it purely on a musical style, you can start to explore other things that suit that particular song. A song like “Absolute Beginners” is a hundred miles away from “Funeral Pyre” or “In The City.”

How about songs like “A Town Called Malice,” which is so tied to the Motown style, or the Who covers that you did? When you were presented with these songs, did you consciously think about staying away from what Keith Moon did, for instance, or did you just play what sounded right to you?

How about songs like “A Town Called Malice,” which is so tied to the Motown style, or the Who covers that you did? When you were presented with these songs, did you consciously think about staying away from what Keith Moon did, for instance, or did you just play what sounded right to you?

We just did it the way we felt we could do it. There’s no point in trying to copy something. You have to make it your own and leave your mark on it. And I think that’s a much more satisfying way to do it. Take our cover of The Kinks’ “David Watts.” The original is quite slow, not so beat-oriented. We obviously recognized it was a really great song, but wanted to do something that represented us more. Strangely enough, The Kinks re-recorded that song after we released our version, and they spun it more like we had: That was quite smashing in a way! And “A Town Called Malice,” it wasn’t long after that when Phil Collins released his cover of “You Can’t Hurry Love.” We were recording at the same studio as Phil at the time, so whether he had heard what we did, or we were all just doing the same thing at the same time, I don’t know. But it did seem to be a bit of a coincidence. [laughs]

What are your feelings about Paul’s reasons for splitting up the band?

When we first got together, we simply wanted to play music. But when we first got signed, people were like, Do you want to do this tour, do you want to do this thing—? And of course we said yes to everything. We even released two albums in that first year. I know Paul felt a great deal of pressure having to come up with the songs to meet the schedule, and I think that might have been a contributing factor to why he wanted to step away from it. And I can understand that; there was a lot of pressure. We were almost silly taking on that amount of work. On the other hand, that was the reason we were doing it in the first place: We wanted to play. We were victims of our own success, if you like.

Advertisement

Paul also seemed to think that we had gone as far as we could go, that there was no more exploration to do, no more musical avenues that we could go down. Bruce and I didn’t feel that way, though. So it was a shame that we split up. I think we could have gone on changing and exploring. We’re hoping to look at some new material now, and we don’t know what direction it might take us. It certainly won’t be a million miles away from the Jam sound, though.

What kind of music and drumming did you listen to before the Jam?

There was some really great drumming going on at that time, people like Ian Paice with Deep Purple, John Bonham with Led Zeppelin, Paul Hammond with Atomic Rooster. They were all a big influence on me. I knew I couldn’t play that way–there was no way I could be as good as Ian Paice [laughs], you know what I mean? But I still loved to listen to what they were playing. And I suppose like most musicians you pull off little bits: I like that—I’ll have a go at that—. You figure out your own way to do them.

Even though these drummers were in what was referred to as progressive rock bands, I still loved the song thing–the three-minute single, which was a lot more engaging than a fifteen-minute rock classic. Even then I thought that was a bit overblown. People started to go back to what I think really matters–a great song from a great band. Advertisement

Why did you drop out of music for a period?

One reason was that during the late ’80s, early ’90s, there was a lot of electronic music coming into the pop word–drum machines, sampling, and that sort of thing. And it didn’t really fit into what I thought a band ought to be. A band should be something that goes out and actually plays. So I thought, I’ll take a break from this for the moment. It turned out to be a longer break than I initially thought. I actually stopped playing for about twelve years. I had to have a bit of a talk with myself: Look, if you’re going to get back into playing, you better do it now before it’s too late–before you get too old. [laughs]

For more on Rick Buckler and From The Jam, go to www.fromthejam.net and www.waterstoneguitars.com.