Gavin Harrison: The Rhythmic Illusionist Is Now Elevating Two Bands, Porcupine Tree And King Crimson

by Ken Micallef

by Ken Micallef

“I stopped focusing on the muscles in my arms and started focusing on the big fat muscle in my head. That’s where the good stuff comes from.”

Forty-five-year-old Gavin Harrison has led a drummer’s dream life. He’s played funk with Incognito and Level 42, enjoyed pop stardom as a member of UK vocalist Lisa Stansfield’s band, performed indie art rock with bassist Mick Karn and keyboardist Dave Stewart, and even took a stab at solo success with his own Dizrhythmia project.

Of course, you probably know Harrison as the mighty prog rock rebel behind the fabulously popular Porcupine Tree and currently as half of the dynamic drumming duo behind prog legends King Crimson. He has a line of best-selling instructional books and DVDs. And he’s been voted the best progressive rock drummer by Modern Drummer readers the last two years. But for all his success, Gavin Harrison has only ever really wanted to be one thing: A working drummer.

“It’s a miracle to make a living out of playing music these days,” Harrison says from his home in Bushey, near London. “I have the utmost respect for any drummer out there, be it in a wedding band, a theater, or on a ship, because I’ve done all those things and I was really happy to be doing them. As a kid I didn’t want to be the greatest drummer in the world. I just wanted to be playing the drums, making a living, surviving, paying the rent–it’s a miracle that we can do that, doing something that we really love.” Advertisement

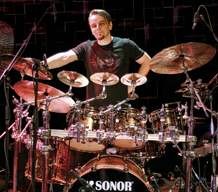

At a recent blistering performance with King Crimson at New York’s Nokia Theater, Harrison plied his dual talents as profound technician and mighty groove monster, revealing a true love for his life’s work. As attendees at this year’s Modern Drummer Festival heard, Harrison is that rare drummer who places groove, feel, and timing on par with technique–and combines it all, effortlessly, and progressively. Harrison’s groove is so seamless, concentrated, and focused that you’d almost swear it’s a machine, not a man.

King Crimson brought out almost the best in Harrison, whether duplicating Bill Bruford’s signature parts, trading orchestral flurries with elder Crimson drummer Pat Mastelotto, or wailing some fiendishly incomprehensible tom/cymbal pattern via his increasingly elaborate setup. His double pedal work was also inspiring and clear within the KC chaos.

But even if you’ve heard Harrison blasting bullets with Porcupine Tree or King Crimson (still on tour as of this writing; a live Porcupine Tree DVD is in the works), those gigs won’t prepare you for the rhythmic impossibilities Harrison delivers in his collaboration with guitarist/drummer O5Ric on their debut recording, Drop (available at BurningShed.com). Harrison’s popular books Rhythmic Illusions and Rhythmic Perspectives and his DVDs Rhythmic Visions and Rhythmic Horizons explain his concepts in mind-blowing detail, but Drop is the soul of the drummer, plain and not so simple. Advertisement

With every drummer of note, you can point to a record where he truly arrived. Where he owns it. It might not be that drummer’s most popular recording, but it’s the one where he innovated techniques that literally put him on the map. Steve Gadd = Steely Dan’s Aja. Tony Williams = Miles Davis’s Four And More. Dave Weckl = Bill Connors’ Step It. Vinnie Colaiuta = Frank Zappa’s Joe’s Garage. Philly Joe Jones = Miles Davis’s Milestones. Drop is the record where Gavin Harrison’s well-earned technical skills and good-foot grooves become one, as he dances through polyrhythmic madness, odd-metered overkill, and illusions realized with both mind and body.

With Harrison’s first cover slot in Modern Drummer, expect dazzling and thorough explanations, for sure. But more surprising is his palatable joy at playing the drums. This guy would be happy playing drums for a weekend warrior bar band, only be sure to let him rethink the approach for every tune–for the better. Even when drumming on the top of a bus–his first gig, dressed up as a loaf of bread–Gavin Harrison sees drumming as life, and life as music.

In The Court Of Robert Fripp

MD: The King Crimson gig at the Nokia Theater in New York was the result of how many days of rehearsal?

Gavin: About twenty-two days just before the start of the tour. And, of course, I did weeks of study at home, listening to and writing out the material, playing along to the music, trying to think about what I could do with it. Advertisement

MD: How did you get the gig with King Crimson?

Gavin: Robert Fripp did guitar soundscapes as a support slot for Porcupine Tree in 2005, and again last year. He would often stay and watch our gigs. He got to see me play a lot, and I asked him to play on the record I did with O5Ric. So he got to hear some different types of playing that I do. And then, out of the blue, he called me up and said he’d like me to join the band. Robert was keen to find a good time slot to put it in, as he wasn’t asking me to leave Porcupine Tree.

MD: Fripp is an enigma to most of us. How did he ask you to join the band?

Gavin: He just called up and said he’d had an idea that Crimson should get back together to celebrate their fortieth anniversary. He felt the double drumming thing was still something he wanted to explore, as they had with Bill Bruford and Jamie Muir and then later with Bill and Pat Mastelotto. Robert said he thought I was the right guy to do it. He did say, “You’ll probably live to regret it,” but I haven’t so far, I’ve enjoyed it.

MD: We’ve heard much about Fripp from Bruford in the past; is Fripp demanding on drummers?

Gavin: Not in my experience. He said, “I want you to play whatever you’ve always wanted to play in a rock band but were never allowed.” He played me some tracks, including one called “Level Five,” where there are a lot of drum tracks and loops going around and Pat playing over the top. I said, “What can you imagine me playing along to this”? It sounded really full to me. He thought for a while, and said, “More.” That was the only piece of advice he gave me. Oh, and he once asked me, “When playing a drum fill, where should it end”? “Uh…” I said. “Anywhere but 1,” he replied, and walked away. Advertisement

At one point I did ask him, “Shall I learn Bill’s parts”? He said, “Don’t learn the drum parts. Just learn the structures of the songs and do whatever you want.” Not demanding at all, really.

Read the rest of this interview with Gavin Harrison in the January issue of Modern Drummer on sale now in print and digital.

Check out these other articles from Modern Drummer about Gavin Harrison:

https://moderndrummer.com/2004/05/gavin-harrison-2/

https://moderndrummer.com/2006/12/gavin-harrison/