Secrets Of Motown: The Tracks Of Their Drums

Everyone knows the drum sound of the Beatles was Ludwig, James Brown’s drummers stoked the fires of their funk revolution with Vox, and the names Premier and Keith Moon have become synonymous. But Motown’s casting call for the drumset that would be instantly identifiable with “The Sound Of Young America” wasn’t quite so single-minded. Employing more of a “Rainbow Coalition” approach, Rogers, Ludwig, Gretsch, Slingerland, and half a dozen no-name, pawn-shop brands were all part of the Motown sound.

Everyone knows the drum sound of the Beatles was Ludwig, James Brown’s drummers stoked the fires of their funk revolution with Vox, and the names Premier and Keith Moon have become synonymous. But Motown’s casting call for the drumset that would be instantly identifiable with “The Sound Of Young America” wasn’t quite so single-minded. Employing more of a “Rainbow Coalition” approach, Rogers, Ludwig, Gretsch, Slingerland, and half a dozen no-name, pawn-shop brands were all part of the Motown sound.

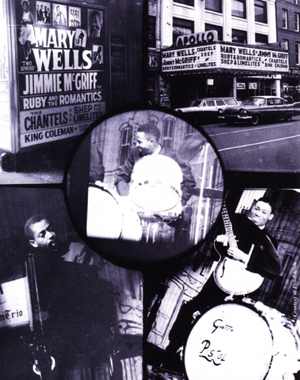

During Hitsville’s early years, the sight of Benny Benjamin or Pistol Allen dragging his own drumkit down the studio steps was a common one. But by late 1963, when Uriel Jones began shifting from the road to “Studio A,” Motown had already purchased a permanent set for the studio. “They were good drums, but they were second-hand,” says Uriel Jones. “They were also a mix of brands. They also had another set of drums down there that they bought a few years later, but those drums were only used when we had a double drummer session. That second set was also just thrown-together stuff.

“See, with Benny,” Jones continues, “you didn’t want to have no big, expensive set of drums down in the studio because he would sneak in from time to time and pawn them. One time we were getting ready to cut a song and Benny was late. Jack Brokensha [one of Motown’s vibists] offered to play the drums until Benny got there, but when he went behind the baffle he said, ‘Where’s the drums?’ Benny had come in the night before and convinced the night watchman that the set was his, and he pawned them.” Advertisement

Because of Hitsville’s constantly evolving studio technology, drum recording techniques down in “Studio A” were always an ongoing experiment. The principal catalyst was the change from Motown’s early 2- and 3-track period to the mid-’60s 8-track era and, finally, to the advent of 16-track technology at the end of the decade. On early recording sessions, like for the tune “Heat Wave,” it was standard procedure for a percussionist to shake his tambourine into a microphone that was already being shared by the snare and hi-hat.

Further complicating the situation was the fact that the drums also had to compete for attention with several other non-percussive instruments that were being simultaneously recorded on the same channel. Crosstalk and bleed were staples of the early sound. The studio’s antiquated Western Electric mixing console only had three tracks (and only two prior to 1961) to accommodate guitars, bass, drums, percussion, keyboards, vocals, and, on occasion, horns and/or strings. However, as the available tracks increased in the mid-’60s, the control over the drum sound was drastically improved because they could now be isolated.

To Benny, Pistol, and Uriel, those changes meant very little. All this talk of channels and tracks was the realm of the room on the other side of the control booth glass. They were more interested in what was happening in the corner of the studio floor where their kit was set up. “We experimented all kinds of ways,” explains Pistol Allen. “We played with the front bass drum head off with some blankets stuffed in it. They’d stick the mic right in there. For the snare, we’d place the microphone right on the head or sometimes on the side near the air hole. For the floor tom, I’d tune it to a G, and then they’d mike it from underneath with a boom stand. Advertisement

“To get the right sound out of the snare drum,” Allen says, “we put electrical tape on the snares on the bottom head. We’d cut two little strips of tape and put one on each side of the strainer to keep the snares as close to the head as possible–you know, to get that tight, crisp sound.”

Jones also recalls duct taping a pad of Kleenex to the top snare head, and he also has a different spin on Pistol’s comments about tuning. “Those drums very rarely went out of tune,” Uriel says, “and besides, the engineers didn’t want us messing around with the tuning anyway. Once in a while if it got really out, you might pull out a drum key and give a half turn or so. But we usually came in and just started playing with what was already there.”

Both Allen and Jones, however, are in total agreement when it comes to the subject of drumheads. “We didn’t care what kind of drumheads we used on the set, and we hardly ever changed or broke them because we didn’t play that hard,” Pistol points out. “It didn’t matter to us what they were. They had tomato catsup stains on ’em, and McDonald’s French fry grease was splattered everywhere. As long as they sounded good, that’s all we cared about.” Advertisement

Reprinted from the July 1999 MD article “The Drummers Of Motown” by Zoro and Allan “Dr. Licks” Slutsky.