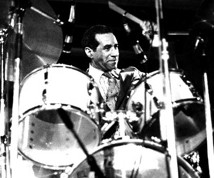

Max Roach: Setting Standards And Raising Bars

If you were to ask any jazz historian to name who they feel is most responsible for setting the standards in bebop drumming, 99.9% of the time you’re going to get one name: Max Roach. Roach wasn’t the first drummer to play in the bebop style. Some scholars argue that it was Kenny Clarke who made the ride cymbal the primary source for timekeeping, and others trace the genre’s origins back to Chick Webb, Papa Jo Jones, and Sid Catlett. But Max was unquestionably the most prolific and widely recognized drummer of the era. This is largely due to his close association with bebop’s forefathers: trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, and saxophonist Charlie “Yardbird” Parker.

If you were to ask any jazz historian to name who they feel is most responsible for setting the standards in bebop drumming, 99.9% of the time you’re going to get one name: Max Roach. Roach wasn’t the first drummer to play in the bebop style. Some scholars argue that it was Kenny Clarke who made the ride cymbal the primary source for timekeeping, and others trace the genre’s origins back to Chick Webb, Papa Jo Jones, and Sid Catlett. But Max was unquestionably the most prolific and widely recognized drummer of the era. This is largely due to his close association with bebop’s forefathers: trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, and saxophonist Charlie “Yardbird” Parker.

In fact, it was a series of recordings that Max made with Parker between 1947 and 1949 (on the Savoy and Dial labels) that solidified his position as bebop’s guiding light. On those records, Roach displays all the techniques that have since become the status quo for small-group jazz drumming. Super-tight tunings, a legato ride cymbal feel, syncopated left-hand injections, unexpected bass drum “bombs,” thematically constructed solos…it’s all there.

And while those classic records are still being studied today, there’s much more within Max’s body of work that’s made a lasting impact on how we approach the instrument, especially in regards to the drum solo. For instance, Max was one of the first drummers to explore the melodic possibilities of the drumset, and he was the first to solo over bass accompaniment, on the track “Jodie’s Cha-Cha” from his 1958 release Deeds, Not Words. Plus, Roach’s explorations in drumset composition helped elevate the drum solo as a legitimate form of musical expression. Two of his most famous pieces, “Blues For Big Sid” and “The Drum Also Waltzes,” which appear on the drummer’s 1966 record Drums Unlimited, have been particularly influential. The latter tune was even revisited by rock artists like Bill Bruford, Neil Peart, and Steve Smith. Advertisement

In the mid ’50s, the ensemble Max co-led with trumpeter Clifford Brown was one of the most exciting of its time. In addition to playing superhuman tempos, this group also helped expand the rules of jazz arranging to include extended vamps, odd-time phrasing, and unexpected tempo shifts.

Over the next two decades, Max’s artistic focus mirrored the musical and political unrest that had swept across America. Many of his albums during this time, like 1960’s We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, were strong statements against racial inequality, while his 1978 duets with saxophonists Anthony Braxton (Birth And Rebirth) and Archie Shepp (The Long March, Pts. 1–2) reflected the drummer’s growing interest in free improvisation. Roach also spear-headed several recordings in the late ’70s with M’Boom, a contemporary percussion ensemble made up of jazz drummers.

Towards the latter part of his career, Roach continued to perform solo and duo concerts, and he dug deeper into the world of classical chamber music. Two of Max’s recordings, 1985’s Easy Winner sand 1986’s Bright Moments, were arranged for his Double Quartet, which featured the drummer’s standard jazz group plus his daughter Maxine’s Uptown String Quartet. Advertisement