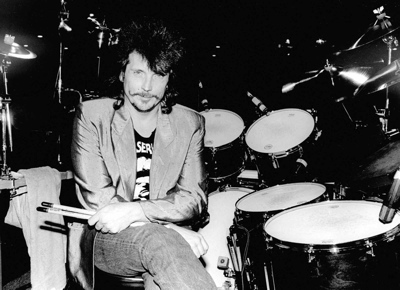

Richie Hayward: The MD Interviews, Part 2

MD Online’s Richie Hayward archival series continues with the recently deceased Little Feat drummer’s October 1995 cover story, in which he talked at length about his playing concepts, his work outside of Little Feat, and the making of the band’s Ain’t Had Enough Fun album.

Interview by Robyn Flans

MD: You have a unique playing style with Little Feat. Can you describe that style and where it came from?

Richie: My style has grown with the band. It started out heavily influenced by blues, rock ’n’ roll, and jazz. Then it got more specific as I got into other kinds of American folk music and other roots music. I discovered New Orleans along the way, and that made a big difference; it loosened me up. I guess I’m a result of everything I’ve heard and how the band has grown in response to all our influences, which are diverse. That’s what makes Little Feat an interesting band. But my playing is just a combination of all the styles I ever heard. I picked up a little of this and that and mish-mashed it all together.

Richie: My style has grown with the band. It started out heavily influenced by blues, rock ’n’ roll, and jazz. Then it got more specific as I got into other kinds of American folk music and other roots music. I discovered New Orleans along the way, and that made a big difference; it loosened me up. I guess I’m a result of everything I’ve heard and how the band has grown in response to all our influences, which are diverse. That’s what makes Little Feat an interesting band. But my playing is just a combination of all the styles I ever heard. I picked up a little of this and that and mish-mashed it all together.

MD: Are there particular drummers who influenced you along the way?

Richie: The first drummer who turned my head was Sonny Payne, who was with Count Basie. It was on some hokey black-and-white TV show, but I was mesmerized. The way he moved was hypnotic, energetic. Playing the drums became a passion for me right then.

Advertisement

Everyone I’ve ever seen has taught me something—whether it’s what to do or what not to do. Sonny impressed me a lot with his passion for the instrument. Other drummers along the line were some of those almost anonymous blues drummers on these old records by people like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. Then, of course, all the jazz monsters like Tony Williams, Elvin Jones, Max Roach, and Art Blakey. I wasn’t really that moved by rock ’n’ roll drumming until the mid-’60s, which is when it got interesting. People like Zig Modeliste, Jim Keltner, and Jeff Porcaro always inspired me.

MD: You said your style evolved with the band, and you’ve mentioned in the past that Little Feat singer/guitarist Lowell George sort of directed and shaped your playing.

Richie: In a way, yes. He helped a lot for sure. He would describe the basic feel he wanted, to the point where I would get started on the idea—then he would suggest something to change it, to make it more like what he had in mind. I would take it from there and try to put all these ideas into some kind of coherent thing and then improvise on it. I always tried to sneak my fills in.

One of the things I do a lot are the fills I play between my left hand and right foot, instead of breaking up the whole feel and doing a fill like it’s separate from the groove. That started happening mainly because Lowell kept telling me not to do fills, because he wanted to keep the feel. The only way I could sneak in the fills that I felt were necessary to progress the tune was by doing things with my left hand and right foot. That way the groove didn’t get completely broken. It turned into something I thought was cool, so I worked it out from there. I’m still trying to work it out. [laughs] Advertisement

MD: What is your concept of using the bass drum within grooves and fills?

Richie: I always thought the bass drum wasn’t just the timekeeper—it’s another part of the instrument. I like the way it feels to use the bass drum as a tom. It expands what you can do with the hat as far as textures go. What I practice are various forms of paradiddles between my left hand and right foot and other combinations of things. It’s really combinations of ones, twos, and threes between the left hand and right foot. I would try all kinds of interplay between the two, and that turned into a whole other bass drum technique. I think it’s important to kick with the bass a lot, but then it’s also interesting to do little flurries around the bass line—within the groove—where you’re not breaking the ride with your right hand but doing little fills with your left hand and right foot on different drums.

MD: The parts in the Little Feat songs seem simple, but at the same time they seem intricately worked out.

Richie: That’s true. It evolves to that, within certain parameters. I always leave myself a lot of room to change and experiment, but the basic part is worked out for that tune and the way the guys play it. Every night we play the songs a little different. It’s interesting to come up with a drum part that’s unique, as opposed to “drum beat number four.”

MD: How do new songs get worked out within the band?

Richie: Whoever writes a particular song will usually come in with a demo tape that has some sort of drum machine pattern and a basic skeleton of a tune. Then we will all start to play it. As each of us separately develops our parts, we listen to what the other guys are doing and we adjust our parts a little bit accordingly. We’ve been working together for so long that this just naturally happens, and each song develops its own little thing that makes it a little different. As everyone works it out, it kind of grows up. A lot of times I’ve lamented the fact that we didn’t play the songs on the road before we recorded them, because they often turn into something much better on the road.

Advertisement

MD: Has the process changed over the years?

Richie: We’ve grown up in that we don’t need to rehearse as many times as we used to. The level of musicianship has risen quite a bit since 1971.

MD: Again, Lowell was such a dominant force….

Richie: On his tunes he was. If someone else had a song, he would have suggestions, but it wasn’t direction with a capital D. We miss him, of course [George passed away in 1979], but we get along a lot better now. Maybe we’ve come to respect each other more and realize how important each of us is to the whole picture. We’re thinking more of the big picture, rather than just reacting to the heat of the moment. So where one of us used to flare up about a certain part, now we’ll bite our tongues and realize it wasn’t necessary anyway; let’s get down to what really matters.

MD: Through the years, your setup has changed quite a bit.

Richie: It’s gotten bigger.

MD: Why do you add particular pieces?

Richie: I’ll add something for more choices in texture in the sound. The notes you play are one thing; the sounds you play are another. The more choices you have for different kinds of sounds, the more you can make it interesting. You don’t necessarily have to pound everything all the time. The second hi-hat came from an experiment when we were working out “Hate To Lose Your Lovin’.” Now the second hi-hat has become part of the kit because we’re always going to do that song. I enjoy the second hi-hat, but I only use it on a couple of songs. I try to carefully pick my spots.

I have found that splash cymbals are a really interesting color, where you can keep the groove going and hit a couple of those things to kind of announce the change from verse to chorus or verse to bridge, without making a great announcement. They’re handy little things. Two, three, or four of them make for different tones, instead of just one that you can only do the same thing with. Advertisement

MD: It seems that your cymbals are clamped down.

Richie: The ride is the only one I really clamp down. The others I clamp a little bit so that the edge of the cymbal will move about four inches.

MD: How does that affect you?

Richie: If your cymbals are moving around too much after you’ve hit them you never get the part of the stick or the part of the cymbal you want. It’s tougher to be consistent, and you have to sort of aim. I don’t like to have to even look at my kit. I like my cymbals to be right where they’re supposed to be when I hit them. You can hit them two or three times quickly and they’re not going to move away from you.

MD: Does it affect the sound?

Richie: Not that much.

MD: You also sit very low at your kit. Have you ever had back problems?

Richie: Never. I like to sit low because my center of gravity is lower, and when both legs are moving all the time, if I’m pushed up higher, I tend to wobble. I don’t feel as secure sitting higher. For me, everything I do comes from the solar plexus area—the center of my chest—and I find that the lower I am, within reason, the more stable that is.

MD: Did you always sit so low?

Richie: I’ve come down over the years. I used to sit up high because I thought that was how you were supposed to do it, since I saw all these old jazz guys sitting up tall. But I play a lot harder than the jazz guys.

Advertisement

The first time I sat at Jeff Porcaro’s drums, he was sitting way down, and I thought, “This is low,” but after I played for a while I thought it felt great. So it’s Jeff’s fault! [laughs] I would think if you’re playing straight out from your chest, arm level, you would have less back problems than if you were hunched over the drums, sitting high and playing down all the time. I’ve been playing for forty-one years, and I’ve never had a problem. I set up my kit to get the most with the least effort, so everything is in a very comfortable place; things are all carefully placed. I don’t have to stretch to get to anything.

MD: Does your road kit differ from your recording setup?

Richie: Not for Little Feat. I record with the whole road kit for Little Feat, except I’m usually armed with fourteen or fifteen snare drums and some different cymbal setups for different songs. That gives the songs unique identities. When I go in with other people, I usually use less stuff.

MD: You also sing with the group. What kind of vocal mic do you use?

Richie: I’m still researching that. I’m using a Shure mic that sits on a boom. I have trouble with long mics because my sticks are flying through that area and I hit them all the time. I even hit the little one I’m using now. I don’t like headsets because the mic is always right there and I make a lot of noises when I’m playing, a lot of grunts and groans and sometimes just plain primal screams. [laughs]

Advertisement

MD: Another challenge of playing with Little Feat must be in working with a relatively large band—seven people. Do you have any tips for playing with a large group?

Richie: Coexistence is very important. You have to listen when someone speaks. Think about what they’re saying and what they’re playing, and try to keep your mind open. It’s really important to pay attention.

MD: There’s a lot of music flying around the stage. Is there something particular you’re usually focusing on?

Richie: That changes from moment to moment. That’s why I say it’s important for me to listen really hard to what’s going on with the other band members. There are more instruments at certain times in a song that are really imperative to tie the groove together. The bass, drums, and percussion will always be the bottom, but there are other instruments that enhance the groove, which will be changing from song to song, part to part.

Other than just playing the groove, I like to kick with the soloist too. Once you get that thing going with whomever is playing the feel, I think it’s really cool for the drums to strike out a little bit and go off with the soloist, as well as keeping it together with the percussion and bass. I got a lot of that from Mitch Mitchell, because he was really able to go out with Jimi and still stay down there. Advertisement

MD: Does the percussionist give you the chance to express more?

Richie: Definitely. Kenny [Gradney, bass] and Sam [Clayton, percussion] are really perfect for me. They like to play it really down the middle, and I like to mess around. [laugh] I love my job.

MD: Do you ever go too far out on a limb?

Richie: Oh, yes. The limb breaks! I’ve learned to recover fast, and hopefully to do so as invisibly as I can. Sometimes you have to just suspend all action for a second, listen, and then come back in as if it were on purpose.

MD: Does that scare you?

Richie: I have a lot of respect for the edge. One of my main rules is don’t practice on the gig. I’ve learned that the hard way. I have to know my limits, although I’m still always pushing just a little bit. You don’t want to play it too safe either. You have to strike a balance. It’s great to take chances, and a lot of my favorite licks were discovered by being so far out in trouble that some accident happened that sounded cool.

Advertisement

MD: How does one play “Dixie Chicken” every night and keep it exciting for so many years?

Richie: We change the arrangement a little bit every year, and we never do it exactly the same twice, especially in the solo parts. What makes it exciting for me is that I never know what Billy [Payne, keyboards] is going to do in his solo, and it’s fun to try to follow it. Sometimes he goes to Venus, sometimes it’s Mars. That’s a challenge. Paul [Barrere, guitar] is the same way.

MD: There must be pros and cons to working with the same musicians for so long.

Richie: You can get insular. You can get to the point where you don’t grow anymore. One of the benefits of this band is that we all play with other people when we’re not working together, so we’re always getting fresh ideas and input from other musicians. Everyone in the band is always looking to grow, and I think that all shows in the music. You have to allow all sorts of outside influences; otherwise you’ll turn into your grandparents.

MD: Little Feat recently added a female vocalist, Shaun Murphy. How has that challenged or affected the way you play?

Richie: It definitely gave the band a tune-up. It’s a whole new direction and approach. I think Shaun’s really exciting. She’s more R&B, blues, and rock rooted than Craig [Fuller, former vocalist] was. He always leaned a little more toward country. Shaun has this knife edge to her performances that’s really exciting. As a person she’s added a whole spiritual uplift to the band as well.

Advertisement

MD: There’s a real urgency and excitement to the new album, Ain’t Had Enough Fun.

Richie: That’s how we feel now. The new material is great, and it’s the most fun I’ve had in a long time. It’s more up my alley. It’s exciting to play, and the band is having a great time with it.

The new album is almost a live album in the way that we recorded it. Most of the instruments, including the vocals and the solos, were recorded at the same time. There are just a few keyboard overdubs that Billy couldn’t do because he only has two hands. Unlike a lot of our other records, it wasn’t cut in a real L.A. studio fashion, where a couple of core instruments cut the track and then everybody sweetens it up.

MD: Are there songs on there that you’re particularly proud of?

Richie: I’m real proud of the whole thing, but there are some I am particularly fond of playing. I really like “Drivin’ Blind.” It’s really fun and has a great drum part. I tried to find a basic pattern for it that was eight bars long and didn’t repeat itself, something that I could basically repeat throughout the song and embellish on in subtle ways. “Cadillac Hotel” is a good return to the old funky Feat stuff. That’s really fun to play. It has the half-beat shuffle thing going for it, which is fun to play. “Romance Without Finance” and “Cajun Rage” are real New Orleans rooted stuff, and that’s always fun to do. You never have to do it exactly the same way twice.

Advertisement

I’m very fond of “Borderline Blues,” because it was written for [artist] Neon Park, who passed away last year. He died of Lou Gehrig’s disease and he hadn’t been able to paint for the last four years. The last painting he was able to do was specifically for our record Representing The Mambo. The new record is in memory of him, but that song in particular was written for him, which is why it is different from the rest of the record. It’s much more somber. The drum part is a combination of the cymbalage that was on “Silver Screen” from the Mambo record and a Peter Gabriel approach for the chorus—no cymbals. I simplified what Manu Katché does with Peter, but I like the way he can establish a really exciting feel with just a tom/snare kind of thing. I can’t play like Manu, so I did my own version.

MD: Of your whole body of work with Little Feat, can you tell us three tracks that would represent who you are within this band?

Richie: I’m real proud of “The Fan.” That was probably the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. Lowell wrote that song in 1971, and we tried for three albums to record it, but it was so difficult we couldn’t play it. We would go into the studio and almost get it, but it wasn’t quite right. There are only two bars of four in the whole song, and it switches time signatures. Then we finally did it live and figured that was the way we could do it. Trying for four years on the song helped us to finally get it. It turned into something. It was really fun to play and it took us to new places every time.

MD: Do you remember how your part came about, other than just playing with the rest of the guys?

Richie: A lot of it had to do with playing with the rest of the band, for sure. One of the challenging aspects of the song was playing the fast 7/8 feel and improvising on it under the solo. There’s one phrase in ten and a couple in what sounds like eight, but it’s really sixteen chopped up into different segments. It got real interesting.

Advertisement

“Cadillac Hotel” on the new record is really what Little Feat is all about. It was that “Rock And Roll Doctor,” “Dixie Chicken” kind of feel. When Billy brought it into rehearsal, it was like putting on a comfortable old pair of shoes that still had a shine on them. It’s not derivative enough of our old stuff to be the same old baked potato—at least we hope not, anyway.

Other tunes that represent us could be either “Rock And Roll Doctor” or “Fat Man In The Bathtub.” They were important stepping stones in my growth because I got to learn different ways to play 4/4 time, different ways to enjoy a backbeat. “Fat Man” was one of my first experiments in second line. It began with that straight Bo Diddley thing you hear in the intro, and through the course of the tune, it changes feel about six times. They’re all at the same tempo, but they feel completely different.

MD: How do you accomplish that?

Richie: I don’t do that alone. The guys all have to be there to help me. I’m thinking about what everyone else is playing and how I can be there with them and tie it together. The big question for me is: How can I be as creative as possible without overplaying? That’s been one of my demons over the years.

Advertisement

I think of all sorts of different things while I’m performing a song. Then I have to sort out what to play. It’s like when you’re trying to talk in front of your parents without cussing—you have to censor what you’re saying. That’s kind of what I have to do when I play, so it’s good if I play about one out of every three or four ideas I get.

MD: Are there other pivotal tracks?

Richie: I like “Mercenary Territory” from Waiting For Columbus too, because the solo toward the end feels like a normal thing, but it’s actually in 10/4. It goes from 10/4 to what sounds like six, but it’s actually eighteen—three bars of six. Then the body of the song is in four. It’s cool because it’s symmetrical in that you can divide it by two. The left hand is doing a backbeat through the whole thing, but everything else is playing these odd times.

“Representing The Mambo” was interesting because it was a style that I had never tried—Latin-infused jazz. That was a whole new pair of shoes to try on, which was fun. I used a piccolo snare instead of a timbale. Since I knew I couldn’t step in there and play it like a real guy, why even try? So I took their influences and applied it to the way I feel. It was an experiment by omission a lot of times, to not play a backbeat at all and still get the feel going, to let it percolate and come up with it here and there. Advertisement

MD: You’ve been spotted playing certain live gigs with the band on a vintage kit. How did that affect your approach?

Richie: I got the vintage kit for our acoustic shows that we did a couple of years ago. New drums were too loud, too live, and just too good for this type of thing. Plus, I felt if I could get an old pre–World War II Radio King drumkit, it would have a deader sound and match more with the tones of the acoustic instruments. It also had a visual impact that made it seem more intimate and casual, which was in keeping with the whole atmosphere.

It seemed like a good idea at the time, but they’re really hard to play because they set up real low. I had to make some adjustments. Plus, I only had one rack tom and two floors. That set me off on a whole different direction. On some non–Little Feat gigs, and even some Little Feat gigs, I try to set up with that little kit and return to my roots for a while. No matter how big your kit is, it’s basically a snare drum, bass drum, and hi-hat. If you keep that in mind, you can keep yourself more centered than if you have five tom-toms and two bass drums and twelve cymbals.

MD: Let’s talk about some of your non–Little Feat performances. You have such a defined style within Little Feat; is it tough when you do your outside work?

Richie: It can be, but I try to go into the outside work with as much of an open mind as I can and try to apply my knowledge to what they want. I don’t go in there and insist that it be my style. I like to go into outside work with the attitude to learn. It’s really good for me to try to get into the other people’s heads and supply what they want.

Advertisement

MD: Jim Keltner mentioned a Ry Cooder album you worked on that blew him and Ringo away.

Richie: It was the first Ry Cooder album. That was in 1970, and he was just setting out. We did a bunch of real eclectic material. We spent a long time in the studio arranging the material. He’d come in with an old Woody Guthrie song, like “How Can A Poor Man Stand Such Times And Live,” and we’d try to put a contemporary, but not modern, arrangement to it. It was a fun record.

MD: Where was Little Feat at that time?

Richie: We were doing our first album. In fact, Ry played on “44 Blues” and “How Many More Years” on our first album.

MD: What three tracks of non–Little Feat material come to mind as ones you’re most pleased with?

Richie: Any of the songs on the Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues album by Buddy Guy. I did that during the Gulf War in London. Working with him was great.

MD: Why?

Richie: Because of the giant, “economy size” respect I have for him as a blues icon, a piece of American history, and an American treasure. It was wonderful. He was playing and singing live, standing eight feet in front of the drumkit, and it was really spontaneous. I got to really get back to my roots. I did two albums with him—Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues and Feels Like Rain, which both got Grammys.

Advertisement

The Robert Plant stuff [Shaken ’N’ Stirred] was interesting—a little less fun than interesting. But it was interesting because I was the only American in an English band. They think differently, both personally and musically, so I had to understand this whole other approach to the music. It’s another culture.

MD: What was the music like for you?

Richie: Robert was obsessed with being modern at that time, which was the mid-’80s. At that time English music had taken this unfortunate twist toward electronic and non-organic music. He wanted to do that, but he had a bunch of guys in the band who were my age and who grew up playing real instruments, so we were making a compromise to be modern for Robert.

I added five Simmons pads to my kit, but I wouldn’t replace the kit. It was a compromise in one way and a challenge in another, which made it a whole new thing. Musically that was really fun, and the guys were great. We had a ball working up the stuff. It turned into something very different from anything I’d ever done. Advertisement

MD: How were the songs presented to you?

Richie: The songs didn’t exist. We worked up the tracks, and Robert made up the lyrics and melodies and sang over them. Then we went in the studio and recorded it. I think we worked the stuff up for six months.

MD: Did you get songwriting credit on that?

Richie: Very little, because the attitude about drummers is always, “Okay, what part did you write”? I didn’t want to get into the fight of it, and I couldn’t care less at this point.

MD: What other outside recording do you want to mention?

Richie: I did a live album with Joan Armatrading that was a lot of fun. It was called Steppin’ Out, and it was early ’79. They called me to do a two-week tour, and they recorded three nights. She called me a week after I’d been in six months of traction, and six months after they cut the body cast off. [Richie had been in a motorcycle accident.] She asked if I was able to play, and I didn’t know if I could or not, but I lied and told her I could. I was using a cane and my right leg was about the size of my arm. I could hardly walk, but I managed to bluff my way through it and we ended up touring for almost two years. That was my physical therapy.

Advertisement

I did a bunch of stuff with Eric Clapton for his most recent blues album, but only one track of mine made it on the record, which I’m playing washboard on, not drums. That was a first for me. And then I had to follow it up and play the tune live with Clapton at Albert Hall, in a suit, which was strange. But for the record, we cut the stuff three or four times, and then after I had gone, he rerecorded it with Jim Keltner. Eric wanted to do it like a real blues record, with live performances. He didn’t want to do any vocal or guitar overdubs, and he was hypercritical of his own performance. He would throw out versions that I thought were great because of one bad note in the vocal, which is not quite the way the blues guys did it. [laughs] But it was great working with him.

MD: When you talk about the life of the session drummer, have there been any tough moments in the studio?

Richie: [laughs] Maybe here and there. In the early days with Little Feat there were some very tense moments in the studio. Those days are over. There are a lot of tough moments in the studio when you’re working out songs and taking chances. It depends on how nitpicky the person you’re working with is. A lot of times you’ll go into a session and the band will start to really cook, but the artist and the producer will take out all the stuff that makes it exciting. It’s hard to bite your tongue and not say anything, but you know darn well they don’t want to hear it from you.

MD: You’ve had some tough moments in life. You mentioned your second motorcycle accident before working with Joan Armatrading. That was a bad time for you.

Richie: I was riding over from a soundcheck from the solo tour that Lowell didn’t make it through. I got forced off the road, and while I was laying on the side of the road, bleeding and with a broken leg, a couple of guys pulled over and said, “We don’t think you’re going to need this,” and they threw my motorcycle in the back of their pickup truck and took off. I think it was really my guardian angel with a sense of humor. I was out of commission for a year—six months in traction and six months in a body cast. It was definitely my lowest point. Two weeks after the accident Lowell died. My first marriage was going down the tubes, and I felt robbed. I wasn’t even able to play the memorial concert for Lowell. I was very down and got into drugs real hard for a couple of years. I was angry.

Advertisement

MD: How do you pick yourself up from that kind of low?

Richie: As long as you’re alive, there’s hope. Having people you love and who love you helps. At the point when I was at my lowest, I got the call from Robert Plant. I wasn’t getting any work here, and he hired me. He hadn’t heard the stories, I guess. I went over there with the determination to put my life back together. I feel real good about life now. So whenever you’re really down, don’t do anything rash, because something great may happen.