Remembering “The Chapin Magic”

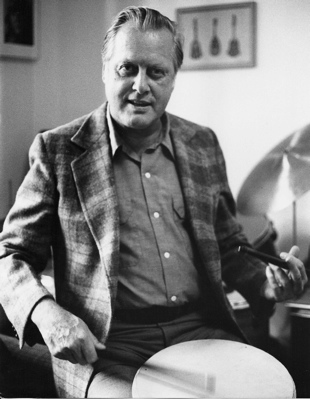

Modern Drummer’s 2011 Readers Poll Hall of Fame inductee is the late drummer/educator Jim Chapin, who passed away in 2009. An anecdote by his friend Rob Birenbaum provides rare insight into the great man’s humanity.

Modern Drummer’s 2011 Readers Poll Hall of Fame inductee is the late drummer/educator Jim Chapin, who passed away in 2009. An anecdote by his friend Rob Birenbaum provides rare insight into the great man’s humanity.

by Rob Birenbaum

Jim Chapin, who died on July 4, 2009, just a few weeks shy of his ninetieth birthday, is known among drummers as “the father of independence” and an expert on the Moeller method. His legendary drumset book Advanced Techniques for the Modern Drummer, first published in 1948 and still in print today, is a bible for our art and was study material for virtually every great (and not so great) drummer for the past sixty years.

Jim was considered one of the most knowledgeable people in the world on drumming and drummers. A conversation with him could cover the teaching techniques of Sanford Moeller, Billy Gladstone, and George Lawrence Stone, while weaving its way through the artistry of Baby Dodds, Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Papa Jo Jones, Max Roach, Joe Morello, Billy Cobham, Steve Gadd, Vinnie Colaiuta, Terry Bozzio, Dennis Chambers, and Jojo Mayer, just to name a few. And if you hung in there, it all made sense! But these words are not about Jim’s technical prowess, his vast knowledge, or his contributions to the art of drumming; they’re about his basic humanness, which I was fortunate to observe and experience many times during our nearly twenty-five-year friendship. Advertisement

I first met Jim in November of 1985, when Dom Famularo, Jim’s longtime student, friend, and confidant, urged me to bring Jim to St. Louis for a weekend to teach privately and present two master-class clinics at Drum Headquarters. When I spoke to Jim on the phone for the first time, we talked about the history of drumming and everything except what he would do when he was in town, which made me unsure as to whether he would be able to handle all we had planned for him. After I got off the phone with Jim, I called Dom and expressed my concerns. I could see the twinkle in Dom’s eyes through the phone line when he said, “You are just beginning to experience the Chapin magic.” Truer words were never spoken.

A few days before Jim’s arrival, I received a phone call from Phill Rock, a customer and local drummer. He told me about another drummer, Clint Rayford, a friend of his and an acquaintance and customer of mine, who was bravely battling the final stages of cancer and was confined to the hospital. Clint, in his late forties at the time, had been one of the top jazz drummers in St. Louis for more than twenty years. He consistently played three to four nights a week during his adult life, while holding down a full-time job at an international chemical company. He continued to play as much as possible well after his treatment began, and his commitment to drumming during this rough period in his life was inspirational to musicians of all ages and styles.

Phill related to me that even though Clint’s condition was deteriorating, he perked up as soon as he heard that Jim was coming to town, and he talked about it often. Phill’s request was small: He wanted me to get an autographed picture of Jim for Clint. I called Jim and explained the situation, and he suggested that instead of a picture he would give Clint an autographed copy of his second book, Advanced Techniques for the Modern Drummer, Volume II, which, at the time, had a retail value of $50. This was the first indication of the kind of person Jim Chapin really was. Advertisement

The next time I spoke to Phill was the day Jim was arriving in St. Louis. I told him that Jim would be bringing an autographed copy of the book. Phill was grateful, but I could tell that there was something else on his mind. He finally said to me, “I know this is asking a lot, but do you think there is any way you could bring Jim to the hospital? I know it would mean a great deal to Clint, because all he’s talked about for the past week is Chapin.” I didn’t know how to respond. All I could say was that I would ask Jim when I picked him up that night.

As I drove to the airport, I ran through in my mind several different ways to present Jim with this unusual request, considering that, at the time, he didn’t know me, Clint, or Phill. I finally decided on the simplest, most straightforward approach. Jim stepped into the terminal, shook my hand, and immediately told me that he’d brought the autographed book. I started to make Phill’s request, and before I could finish, Jim said, “Great, do you want to go to the hospital now”? I explained that it was too late and I would have to arrange it with Phill. Jim said, “You just tell me when, and we’ll do it.” This was the second indication of the kind of person Jim Chapin really was.

We had a grueling schedule planned for Jim: He arrived Friday night, he would teach all day Saturday, present two clinics on Sunday, and fly back home Sunday night. So the only time for the hospital visit was Saturday night. The arrangements were made, and on Saturday night at 7:30 p.m. (after Jim had taught nine one-hour lessons in a row without a break), we left on our mission. Advertisement

We arrived at the hospital about 8 p.m. and were met in the lobby by Phill. He looked shaken and told us that Clint had had a bad day, was a bit out of touch, and had been dozing off. Phill suggested that we not go in, but Jim would have nothing of it. He firmly stated, “I’m here. I want to do this. Let’s go in.”

We walked into the hospital room. Phill roused Clint, and after the obligatory greeting, Phill and I retreated to two chairs in the back of the room. Jim sat down on Clint’s bed and took over, displaying a bedside manner that would humble the most skilled doctor, nurse, or social worker. He presented Clint with the autographed book, a pair of sticks, and a practice pad. Jim and Clint talked about drums, drummers, drumming, and nothing else. Though he was confined to the bed, Clint held the sticks and played the pad. Jim even gave him a few pointers on technique and showed him some exercises he could work on.

When some earlier-administered medication began to take effect and Clint felt the first signs of drowsiness, he said it was time for us to leave. Jim leaned down, embraced Clint, and said, “I love you, man,” and I know he truly meant it. And I also know that for the twenty minutes Jim was in that room, Clint forgot he had cancer. Advertisement

This was one of the most moving and powerful experiences in my life—and I was just an observer! My entire weekend with Jim was memorable, and I had the great fortune of sharing many other special times with him over the subsequent years. But nothing could equal that extraordinary twenty minutes.

Too often, we as musicians are only concerned with a player’s technical ability, and as a result we miss what is most important: the person. Look deeper and you could be pleasantly surprised and richly rewarded. For those of you who had the opportunity to know Jim during his long life, I hope you were as lucky as I was, and that you too experienced “the Chapin magic.”

Rob Birenbaum is the founder and former owner of the Drum Headquarters shop in St. Louis, Missouri, and of HQ Percussion Products, the manufacturer of RealFeel practice pads and SoundOff drum mutes. He is currently the manager of the Five-Star Drum Shops group (an organization he cofounded in 2000) and a consultant to Brady Drums. Advertisement