Kenney Jones: British Drumming Royalty

by Adam Budofsky

Among the most dynamic of all the groups who came out of England in the mid-’60s was the Small Faces, featuring singer/guitarist Steve Marriott, bassist Ronnie Lane, keyboardist Ian McLagan, and drummer Kenney Jones. After a number of popular R&B-influenced singles, the Small Faces developed a distinct sound on the 1968 album Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake, which many rock scholars rank alongside the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, the Who’s Tommy, and the Zombies’ Odessey And Oracle on the list of great art-pop records.

Kenney Jones’ warm but tough drumming approach supported the band through all their great musical advances, including their post-Marriott incarnation as the Faces, featuring vocalist Rod Stewart and guitarist Ron Wood. Eventually Stewart’s ascending solo career overshadowed the band’s albums, and the Faces ground to a halt in the early ’70s. Kenney, however, would be back on the map by the end of the decade, replacing the late Keith Moon in the Who, successfully touring with the band through a difficult time and recording the albums Face Dances and It’s Hard.

Jones’ drumming career doesn’t stop with the Faces and the Who, though. He’s racked up an impressive list of other credits, with artists as diverse as ’80s pop chanteuse Sheena Easton, the Moody Blues’ John Lodge, early rock heroes like Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis, and his own band, the Jones Gang, who released a self-titled album and toured the States in 2005. That year Modern Drummer talked with Jones about many of the great recordings he’s made during his illustrious career. We began by asking Kenney about the self-titled 1966 debut by the Small Faces. Advertisement

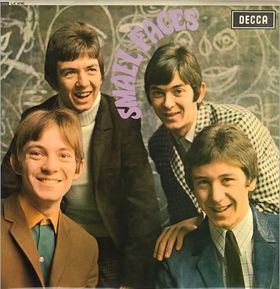

The Small Faces The Small Faces (1966)

The Small Faces The Small Faces (1966)

Glyn Johns was our engineer right from the word go. I was very fortunate, because at that time Glyn was known as the best engineer in England, if not the world. He was an expert at getting great drum sounds. Basically it was a very simple setup: just a couple of overheads and a snare mic’. You really get the ambient sound of the drums that way. Glyn would experiment with sound as well—echoes and sustains and stuff.

Also, I don’t know what it is, but I’ve got a completely different sound from most other drummers. For rock gigs I play with my left stick turned around the other way [butt end]. I also hit the drums a lot harder than most players—or so I’m told—and my tuning is completely different from most drummers’.

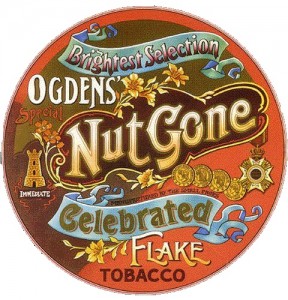

The Small Faces Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake (1968)

That was a fantastic album to record. People say it took us a year to make it, but it didn’t. The actual recording didn’t take long at all. But by that time we were doing lots of gigs, and we had to fit recording in between. Ogden’s was the first concept album of its type. It was innovative, and it took us somewhere else. One of the things that was probably in the back of Steve Marriott’s mind at the time—which made him decide to form Humble Pie—was the fact that we were all feeling the same: “How do we follow this”? We were all young, and we shouldn’t have been so impatient. But I’m reworking it into a full-length animated film, redoing the soundtrack as well. Pete Townshend is involved in the writing. Advertisement

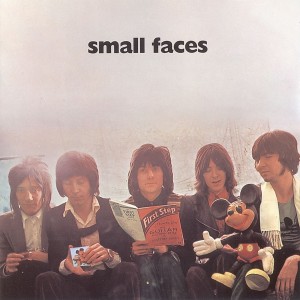

The Small Faces First Step (1970)

After Steve Marriott left, we were all desperate to get rid of our pop image. We were a completely new band, with Rod Stewart and Ron Wood on board. We were much more blues-oriented now, and a lot heavier, and we could go into a different musical atmosphere. We were quite excited about that. We hadn’t played a lot together, though, other than jamming and stuff like that, and we didn’t have a lot of songs. So we had to literally write songs on the spot. So that album was when we first started discovering each other.

My drumming approach did have to change, as did everyone’s. It was very loose one minute, very tight the next, and very blues-oriented the next. It was quite strange, and I only realized that recently, when we did a tribute to Ronnie Lane at the Albert Hall. Pete Townshend came on and did a song, and so did Ron Wood. One of the songs we did in rehearsal was “Flying,” though Woody wasn’t there for that one. As we started it, I realized it didn’t feel the same. It was quite strange. I said this to Woody last week, and he said, “Ah, that’s because you needed me there, you needed the Faces to do that.” That song is something only the Faces could do. It sounds incredibly simple on record, but the minute you go and play it with someone else, it doesn’t happen. The Faces are unique in playing so laid back.

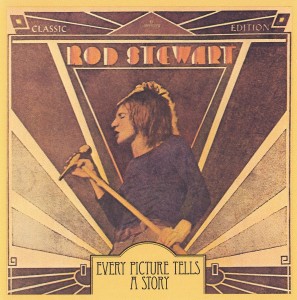

Rod Stewart Every Picture Tells A Story (1971)

Rod Stewart Every Picture Tells A Story (1971)

We used to do some of Rod’s songs live with the Faces, and “I Know I’m Losing You” was one of them. I’ll never forget when we recorded the studio version of that. I was watching a film at home and Rod called up and said, “We’re in the studio, can you come and do ‘Losing You’ for me”? Luckily it was only five minutes away. So I drove to the studio, got on the drumkit, did the track with the drum break in it, and finished. Then I went back to my house and watched the end of the film. That’s how quickly we did that one. Advertisement

The song was never meant to have a drum solo, just a drum break that Rod would chant over. But in time the drum break got longer and longer, eventually turning into a bit of a solo. I never view it as a drum solo, though. If I were to choose to do a solo, it wouldn’t be that kind of rhythm, and it wouldn’t be that tempo, although I’ve gotten used to doing it by now. There’s lots of press rolls and triplets with the bass drum. Oddly enough, while I was doing it I kept thinking about “Let There Be Drums.”

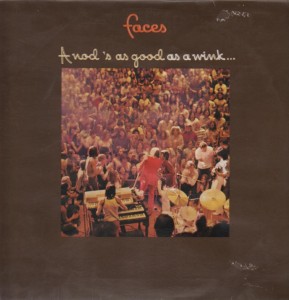

The Faces A Nod Is As Good As A Wink…To A Blind Horse (1971)

“Stay With Me” from that album is actually difficult to play, as we found out when trying to do it in my band. It’s 16ths on the hi-hat all the way through, and in order to get the groove right you have to get the tempo bang-on. Tempos could be a nightmare in the Faces, because you didn’t know what everyone had been up to the night before!

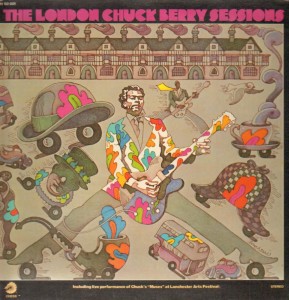

Chuck Berry The London Sessions (1972)

Chuck Berry The London Sessions (1972)

Chuck was great to work with. He’s one of my heroes. I think that was the sessions where we did “My Ding-A-Ling.” A funny old song, that one. [The tune, a huge latter-day hit for Berry, is included on the album, but in a live version featuring Robbie McIntosh on drums.] Chuck loved playing with us British musicians. It’s funny, I remember he kept getting his fingers stuck in the strings. I thought, “Man, he’s got big fingers.” But he was as great to work with as I expected. You hear all these horror stories about Chuck Berry, and I know some of them are true, but we didn’t see any of that at that time. Advertisement

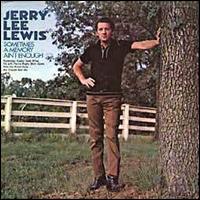

Jerry Lee Lewis Sometimes A Memory Ain’t Enough (1973)

That was a similar thing to the Chuck Berry session. Jerry Lee came to London to record, which seemed to be the fashion at the time. He was great to work with too. It was lovely, because it’s nice having someone like that, one of your heroes, appreciate your drumming. But he did lose it one day in the studio when this young record exec came in and said, “Oh Jerry, you’re fantastic. Love to have you here, here’s a bottle of champagne….” “Well then we better drink that straight away!” Apparently he wasn’t supposed to drink at that time. He had one glass and it was like someone turned a switch on. He just kept picking on this young guy, “I can whip you around the block!” and all this crap.

It was never difficult playing with guys like that, though, because a lot of them were my influences anyway, so I played in their style naturally. Booker T. & the MG’s was always on my record player, for instance. Al Jackson will remain my hero till the day I’m gone. He’s definitely the man who knew his place as a drummer. Alongside all that was the Shadows, Gene Vincent—but Chuck Berry especially, because I loved his lyrics. And he had great beats to play as a drummer. I also loved Ray Charles, Jimmy McGriff, Mingus, and all that. Before anything else, I was very much influenced by jazz. People don’t realize it, but I play jazz quite a bit. From a drummer’s point of view it’s the only way to get your rocks off. And to be honest, in order to play proper rock ’n’ roll beats, you must have a swing to it. Rock ’n’ roll beats come from the jazz, really.

Kenney Jones “Ready Or Not” single (1974)

I did that just because I needed to know if there was another side to me, that I could do it if I wanted to. And I found that once I did it and got it out of my system, I didn’t need to do it anymore. Advertisement

The Rolling Stones It’s Only Rock ’N Roll (1974)

You have gates in London leaving Richmond Park to different parts of the city: I lived on Kingston Gate, Mac lived on Sheen Gate, Woody lived on Richmond Gate. The park is massive, there are thousands of acres. And you had to drive all the way around it at night if it was closed. Woody would always call up just as I was getting into bed at about midnight or something and say, “Kenney, we haven’t got a drummer.” In those days you never know who was going to be in the studio. One day Bob Dylan was there, so we just had a play; another time I go there and Clapton was there. This time it was just Woody and Mick Jagger.

Woody had just got all this new equipment for the studio, so he was in there twiddling knobs and pissing about, and he left me and Jagger sort of playing together. Mick was playing guitar and singing a bit. I just played along and he said to me, “That’s nice, do that.” And I said, “It’s only rock ’n’ roll,” and he said, “Yeah, but I like it.” And then we started to sing it. We just played that riff and it kept going. Then Woody recorded it and put guitar on it. Now, it was only supposed to be a demo. Later I found out that they went in to try to record it properly but couldn’t capture the feel, even with Charlie, which I found strange. So they put it out the way it was. I felt so guilty, so when I saw Charlie I said, “Charlie, I’m told they kept my drumming. I’m really sorry, it’s not the way I wanted things to work out.” He said, “Ah, it sounds like me anyway.” He’s great, brilliant!

Tommy original motion picture soundtrack (1975)

Tommy original motion picture soundtrack (1975)

I was on a lot of Tommy. One of the funniest things that happened during the recording was when Moony came to see me record. He was a friend anyway. Tony Newman did a couple things on there as well. So one time when the three of us were in the studio Moony just locked all three of us inside—and no one could get in. There was a bar up inside the studio, and we were drinking in front of the control room window, just getting pissed in front of everyone else for an hour or so, which was driving them nuts. They were two nutty drummers, I’ve got to tell you. Tony Newman was worse than Moony! Advertisement

Joan Armatrading Show Me Some Emotion (1977)

That’s another one Glyn Johns engineered. The first time I met Joan she couldn’t remember any of the musicians’ names, so she’d talk through Glyn: “If you could tell the bass player…and tell the drummer….” Eventually Glyn turned around to her: “Do you realize who all these people are? They’ve all come to help you out here, and you don’t even know their names!” Later I realized that she was just incredibly nervous, and once she broke through that, she was great. I adore her. She knew exactly what she was on about—very dynamic in her way of playing, and very positive in her voice.

Pete Townshend Empty Glass (1980)

When I joined the Who, Pete was doing his solo album Empty Glass as well. “Rough Boys” was one of the tracks we did. I said to Pete, “Ah, this should really be a Who song.” There’s actually a couple of songs on there that I think should have been Who songs. But he kind of went, “Ooh, I don’t know.” I think I said the wrong thing, but I meant it.

They got a nice drum sound, too, but it wasn’t like the Who stuff, which is the sound I would have preferred. But then again, I had just joined the Who and I didn’t know quite how the band was thinking about their sound then. Pete said to me when I first joined the band, “Now we have an opportunity to be completely different.” So I thought, Okay, maybe that’s the way they want to go. But it was kind of weird. Advertisement

The Who Face Dances (1981)

Playing with the Who…you can call it unique. The bass player was my foot, and I was playing in the middle of two lead guitarists. One “guitarist” had the bass end of it and one had the high end to it, and I had to fit in somewhere in the middle. That’s when I started to learn different bass drum techniques and ended up having the fastest foot in the industry at one point, without using two bass drums. I also started to deliver a punchier feel; I got fitter and my arms got bigger. You had to be 110% fit to play with the Who, because it was like three and a half hours of non-stop drumming. The only rest I got, really, was on “Behind Blue Eyes.”

Playing live with the Who was probably the best part of being in the band for me. We toured quite a lot, and I got stronger and more with it. “You Better You Bet” in particular was a good recording. Changing the backbeat between the snare and the tom was just my handle on it.

The Who It’s Hard (1982)

The Who It’s Hard (1982)

I liked playing “Athena” mainly because when it got to the middle there was that “rababababa” part. I like those types of things that were different. “Eminence Front” I quite liked as well because that was different for them. There are some tricky bits on there on the bass drum. At that time there was a fad of that kind of beat going around. I just had to do it slightly different from everybody else. Advertisement