In the Studio: Making inFAMOUS

This piece originally ran in the March 2010 issue of Modern Drummer.

by David Ciauro

How a hot new video game inspired one of the coolest percussion-oriented soundtracks in recent memory.

The video-game industry has become a major moneymaking machine. And it’s likely to continue to grow, possibly surpassing the movie and music industries in terms of revenue. (Working drummers, take note.) Companies such as Sony invest a lot of time and funds in creating original scores for games, using top studio musicians and composers to create musical landscapes that enhance the gaming experience.

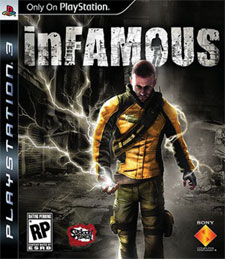

Talking with Jonathan Mayer, longtime drummer and music manager at Sony Computer Entertainment America Inc., about the eccentric drum-centered score for the original version of the PlayStation 3 exclusive inFAMOUS (a sequel, inFAMOUS2, was subsequently released with a different soundtrack), we were surprised to learn how much emphasis SCEA placed on ensuring that the soundtrack was as interesting and unusual as the game itself. The scenery in inFAMOUS is that of a decimated city, and the composers wanted to match the music to the landscape. This required a cacophonous hybrid of unconventional percussion instruments and electronica.

Talking with Jonathan Mayer, longtime drummer and music manager at Sony Computer Entertainment America Inc., about the eccentric drum-centered score for the original version of the PlayStation 3 exclusive inFAMOUS (a sequel, inFAMOUS2, was subsequently released with a different soundtrack), we were surprised to learn how much emphasis SCEA placed on ensuring that the soundtrack was as interesting and unusual as the game itself. The scenery in inFAMOUS is that of a decimated city, and the composers wanted to match the music to the landscape. This required a cacophonous hybrid of unconventional percussion instruments and electronica.

Enlisting the collaborative efforts of underground electronic musician Amon Tobin, world-renowned composers James Dooley and Mel Wesson, and electric cellist Martin Tillman to score the music and cinematics, Mayer spearheaded the project, while also assuming the role of drummer/percussionist for the sessions. The end result is a creative and imaginative score that’s brooding, spacious, and rife with percussive anarchy. Advertisement

Hearing the soundtrack, it’s nearly impossible to decipher exactly what you’re listening to, even when you have pictures of the studio setup in front of you. The innovative thinking and unique instrumentation, used in conjunction with the dark, atmospheric electronic score, the mutilations and manipulations of live drum patterns and grooves, and an overall cinematic melancholy, makes for one fascinating experience. We spoke with Mayer for more on how it was all put together.

MD: How did you get the idea of using real-life objects as percussion?

Jonathan: The temporary score provided by Sucker Punch, the game’s developer, consisted of tribal-sounding drum loops. We thought that was a good direction, but typical. So looking at the game’s apocalyptic landscape, we thought of using refuse and rubble as our instruments.

MD: How did you achieve that?

Jonathan: Both Amon and Mel have backgrounds in electronic music and an ability to create dark, cinematic atmospheres. It became a very collaborative process, with Amon as the driving force in the studio as the producer.

Advertisement

MD: Since you strayed from conventional percussion instruments, how did you find which objects and sounds worked best, and how did you go about selecting them?

Jonathan: It took a bit of experimentation. Before we started recording, we went out one day with a metronome, a bag of sticks and mallets, and a nice field-recording unit. We spent about twelve hours at a scrap yard where they crush cars, rummaging through junk and hitting things and recording what seemed to fit the mood of the game. Of course, everything we really loved sonically was far too big and unwieldy to ever bring back to

the studio.

MD: Anything in particular?

Jonathan: There was an old thirty-foot-long street lamppost that was hollow. We miked the inside of it, and it sounded great when played with xylophone mallets. Amon used our field recording of that all over the soundtrack. We also miked the insides of some cars that were to be scrapped and, using various implements of destruction, smashed the cars to pieces and got some great destructive sounds recorded.

MD: What are some of the objects you brought into the studio?

Jonathan: We used trash cans and lids, terra-cotta pots, buckets, water jugs, and broken glass that we fashioned into scrapers and shakers. We also used a euphonium, a trumpet, a Chinese zither, and some stringed instruments in ways that players of those instruments would consider quite offensive.

Advertisement

MD: How did you configure the gear?

Jonathan: I envisioned a big cage rack, so I drew up my idea and sent it to Gibraltar. They sent me the pieces I needed to build it. Once we put it together, the trial and error of learning how to play our creations began. I played the euphonium with wire brushes, and that became our go-to hi-hat sound. We basically tuned the strings of the cello so they resonated harmoniously, and I beat the poor thing senseless with sticks or a bow. The zither is a huge feature in the score, and I pretty much tortured that too, playing it with sticks and dropping objects on it from various heights.

MD: What real drums and percussion instruments did you use?

Jonathan: We had Octobans, concert toms, bass drums, taiko drums, two drumsets, and a slew of cymbals. Amon was very creative about ways to manipulate and play the drums. He thought of stretching bungee cords across the heads of the concert bass drum, and we essentially made a giant banjo out of it. Plucking the bungee cords made an intense bass sound that provided a bunch of the low hits heard throughout the soundtrack. We also drummed on the bungee cord with sticks for another interesting texture. Amon poured dried beans onto the batter head and the beans rattled, making a giant snare-like sound that we used a lot too.

One of the drumsets I used was a six-piece Pacific kit—10″, 12″, and 14″ toms, 16″ floor, 22″ kick, and 5×14 snare—and Amon had me strap cymbals to the batter heads, ones that matched the sizes of the toms and snare. It produced a very brash, trashy, explosive sound. I also used my own kit, which is a five-piece Yamaha Maple Custom, for more standard parts. Advertisement

MD: What type of cymbals did you use?

Jonathan: I’ve been into handmade cymbals in recent years, like Istanbul and Bosphorus. They worked really well on this project because they’re very dark and have weird overtones. We also had a huge array of Zildjian cymbals, which sounded beautiful—but we weren’t really going for a “beautiful” vibe, so we used the handmade cymbals most.

MD: How did you track everything?

Jonathan: Being that I was the only drummer, I would just go from station to station playing various grooves, rhythms, and polyrhythms to a click. An ensemble sound was created via overdubs. Those recordings were then sent to Amon and James to be chopped, shaped, and manipulated to fit their arrangements.

MD: Since you were going for unconventional sounds, did you use odd microphone setups?

Jonathan: Some standard drum mics were used, like an Audix D6 for the kick and Seinheiser 421s for the toms. We also used two stereo-pair DPA omnis and an Earthworks three-piece drum-miking kit. Amon really liked the sound of a stereo pair placed really low over the kit, basically just above my head. It produced a dry, tight recording.

Advertisement

For the trash cans and percussion oddities, we made use of several contact mics. We found that recording trash cans with good mics sounded too much like a trash can. We wanted an artificially dramatic sound, so the contact mics worked best.

We also found that leaving all the mics and contact mics on—no matter what we were recording—picked up some great resonant sounds. That created an awkward resonating chamber that added to the bizarreness of what we were doing.

MD: How long did the scoring take?

Jonathan: Ten months, averaging about eight to ten hours a week of studio time. We ended up with 160 minutes of finished source music, custom written for the game. The game itself can take anywhere from eight to thirty hours to play, depending on how much exploring you do, so we made several remixes and variations on the source material, making things more intense or less intense, for example, and we shipped 400 minutes of music with the game.

Advertisement

Working with the programmers over at Sucker Punch, we developed a system that uses playlists instead of individual music cues, so anytime a player hits a checkpoint in the game, there are several choices the game can make musically. That keeps the player from hearing the same music at the same parts every time he or she plays.