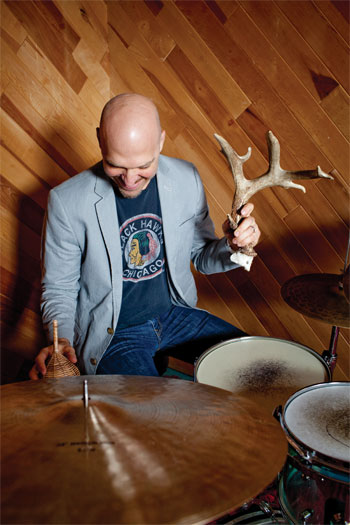

Dave King of the Bad Plus: Web-Exclusive Interview

by Michael Parillo

To read the Dave King cover story from the October 2012 issue of Modern Drummer, pick up a back issue or order a copy from the App Store.

“I’ve always been attracted to the mystery of things, not just the road map,” says Dave King of the Bad Plus, MD’s October 2012 cover star. And indeed, King sometimes resists analyzing his own wide-ranging music on a technical level, letting the sounds and the feelings they evoke resonate within each listener in a personal, individual way. But he’s always happy to open up about the creative process and the many artists who have inspired him. Here, in this Web-exclusive companion to our print feature, King talks about his musical upbringing and sheds more light on the Bad Plus—which, in addition to the drummer, includes bassist Reid Anderson and pianist Ethan Iverson—and its new release, Made Possible. (Under his own name, King has also recently put out an album of mostly standards, I’ve Been Ringing You, with bassist Billy Peterson and pianist Bill Carrothers.)

“Anything that can be a challenge or a complex emotion, we’re at least interested in it,” Dave says of the Plus’s inclusive mindset, where jazz mingles freely with a host of other concepts, including rock, minimalism, electronica, and twentieth-century classical music. “It’s always like: Yeah, let’s do it.”

MD: You play high-concept music, but nuts and bolts help construct it. You clearly put in your time getting things like speed, smoothness, and dynamics, and you can reference so many styles.

Dave: My life experience comes from checking out everybody. I checked out Vinnie Colaiuta and Dennis Chambers right alongside Beaver Harris, Tony Williams, Billy Higgins. I mention Beaver Harris or Sonny Murray or Rashied Ali—all my quote-unquote free heroes—but I checked out Dennis Chambers and Steve Gadd right alongside my Elvin fixations, or whatever. My heroes from the generation or two before me, the Joey Barons, or you can go further back to Jack DeJohnette and Billy Hart, they’re always the quirkier musicians. These guys have tons of technique, but when you strip away the obviousness of technique it’s like modern movements in art—you’re getting to some other, very sophisticated space. Advertisement

Fusion guys are inside me just like African drumming is inside me. I always want to be a modern-thinking improvising musician, but I also play rock music, pop music. I’ve done studio work. I’ve played on film soundtracks. I don’t have the Milford Graves creed; I’m not this pure life force of free jazz. I also dig ’80s John Scofield records, you know what I mean? I like Dio—I like Vinny Appice as much as I like Elvin Jones. For real.

MD: It’s not as if Vinny necessarily comes out, but you obviously draw from all sorts of places.

Dave: I really respect the idiosyncratic musician, and I don’t care what school of music, from Chuck Berry—who to me is very eccentric and idiosyncratic, with a mysterious rhythmic feel that’s unbelievable—to Bill Frisell to, of course, all the jazz giants. It’s always the ones that were bent away. John Coltrane was a bent musician. It wasn’t like he found what he could do better than anybody and did it; it was a constant search, turning his back on certain fandom and critical acclaim to go completely free. I always want that personality involved, no matter what the music.

My biggest complaint about lots of rock music today is: Where are those totally personality-driven drummers? Where are those Stewart Copelands and Keith Moons? Or Pete Thomas—what an unbelievable personality on the drums. Where’s the twenty-four-year-old Pete Thomas? I’d love someone to hip me to it. And I don’t mean chops. I mean personality, feel, style. Advertisement

MD: So you listened to jazz, as well as rock, early on?

Dave: Growing up in Minneapolis I was able to see so much great music coming through, from the Walker Art Center to the great jazz clubs. By the time I was in my teens I was checking out all the jazz that would come in, and I saw so many great drummers, from Elvin to Tony. I saw Tony Williams play the old Artists’ Quarter in Minneapolis when I was fifteen.

I will say that the heaviest thing for me was getting to grow up in the city where the great drummer Eric Gravatt lived. He still lives there. He was in Weather Report and also played with McCoy Tyner in the ’70s. Then he moved to Minneapolis and had a family and played on the scene there and became a prison guard, where he was for twenty-some years. He retired a few years ago and went straight back to McCoy.

He’s truly one of the heaviest drummers of all time. Gravatt is unbelievable. He’s a contemporary of Tony Williams. I would go see him play from age fifteen on, religiously, and I’d grill him, question him, take whatever form of lesson I could from him. Advertisement

I was studying with another great drummer from Minneapolis, Joe Pulice, who turned me on to Eric, and through that I learned so much about presence. Eric has a huge personality and presence on the instrument and plays very hard, Tony Williams style. And he has an unbelievable, legit swing and from-the-era feel but is also this incredibly modern-thinking musician and composer, and to be around that was so heavy for me. I can’t thank him enough. Every time I play I feel some form of influence from him. And of course from Paul Motian.

But when you’re in your early teens, when you become aware that stuff is in the world—beyond, you know, TV and rock radio—you’re soaking it in, and it’s the text of your life. At the same time I was listening to the Who and whatever, I was wanting to hear something else, and progressive rock led to jazz. I can’t give it up to Gravatt enough as a major influence on my playing. Drummers know that he’s one of the folk heroes of a certain era of drumming.

The Bad Plus’s Made Possible

MD: What was the preproduction process for Made Possible?

Dave: We worked up the music, playing some of it live. It was one of the shorter periods of getting the music together and then recording it. We usually play the music live for at least several months before we record, to really live in it. It’s rare that we bring in a piece even near recording without having played it live. The only time we did that was [the 2008 all-covers set] For All I Care. We hadn’t performed live with Wendy [Lewis, singer] before we made the record; we’d only rehearsed the music. With Made Possible there were a few that we’d only played a few times. Advertisement

In fact, there was a little bit of sweating going on with some of it. With the Bad Plus there’s so much ownership of it and conceptual thinking going on—it’s not like you put a chart in front of someone and nail it. Everyone can read and do the session-guy thing; the reason we’re doing this is so our music doesn’t sound like we’re just reading something down. It’s almost like method acting—everyone really wants to know the character more.

It ended up being a very good session, and we did it in two days when we had four. We kind of messed around and played a few improvised things—we ended up doing the Motian tune “Victoria”—and on the third day we made some extras, bonus tracks based on some improvisations and things. We ended up feeling really good about what we were able to do in the two days. It’s the classic thing with that band—everybody sweats something, and then it just rolls.

MD: How many days did it take to record your previous album, Never Stop?

MD: How many days did it take to record your previous album, Never Stop?

Dave: Similar, two to three days. I don’t think we’ve ever tracked more than three days for a record, including For All I Care. The vocals took a little longer; Wendy sang scratch tracks, and then…. You know that record, right? Advertisement

MD: I do. In fact, your take on Milton Babbitt’s “Semi-Simple Variations” has been knocking my socks off.

Dave: Awesome. Thanks, man. We’re bringing out the sexy groove in Milton Babbitt. [laughs] You’ve seen the video with the girls, right?

MD: No, I haven’t.

Dave: Oh, man! One of the greatest things we ever did. Go to YouTube and check it out. We made a video with three Mark Morris dancers, dancing to Milton Babbitt. They choreographed it, and we filmed it in New York, in a loft. And Milton Babbitt saw it before he died, and he loved it! He was supposedly so amused by people playing his music that way and then having girls dance to it.

MD: Do you treat recording differently from performing live?

Dave: I attempt to put myself in a setting to get into a good performance vibe when I make a record, like finding a great live room where you can play the acoustics and it’s not just this isolated situation with headphones, which can be very difficult with sensitive, dynamic music. I’ve found that one of the great challenges of my career is to make that definitive version of a song that’s different every night. It’s trying to be in a great headspace and a comfortable physical environment. We always go for the first take, because they start to go down after that.

I definitely try to make it like a great live show, because it ultimately is live music. Getting out of your head, out of knowing that this is the definitive version of something that you’re quite close to, you just gotta let go at some point: “That’s it; I’m not gonna do it any better than that.” And maybe I did it better than that in Cleveland six months ago, and man, I wish I had that version…. [laughs] Advertisement

MD: If you’re pretty sure you didn’t get it on the first take, will you move to another tune and get back to that one later, or will you do a second take?

Dave: A lot of times we’ll do a second take and sometimes a third take. If people aren’t feeling it, then we’ll come back. But most improvising musicians totally misjudge the happening shit in the moment. We recorded “In Stitches,” and none of us, without listening, thought we got it. And we couldn’t do another one right away, because that’s one of those epics. Then, two hours later, we listened to it, and we were looking at each other, like, “Oh my God—we could have gotten the best one we’ve ever played.”

Sometimes you just get it right off the bat: “That’s it.” You go in and listen, everything’s cool, and you move on. There’s no greater feeling when you’re making a jazz or improvised music record than getting to move on. [laughs] Because the nature of the music is to play it and be done; it’s not to labor over an overdubbed chromatic tambourine part.

The Boys in the Band

MD: The Bad Plus has been together for a long time now. Are you guys pals?

Dave: Oh, yeah. Reid and I have been playing together since 1985. We met when we were fourteen, and we played in high school. The first time the three of us ever played together was 1990, in Reid’s parents’ living room. Ethan was like sixteen at the time. We kind of grew up together as musicians, and throughout the ’90s, when they moved to New York and I was living in L.A., I would come to New York with different things and we would play on and off with each other and were fans of each other’s groups. So we were always in each other’s corner. Advertisement

Ethan and I did some trio stuff in the mid-’90s, and we’d always start talking about how the three of us had to play together, because Reid and Ethan were playing together a lot in New York. We came together in 2000 and played, and it was an immediate hookup. We knew there was something there that we had to pay attention to.

We’re still very good friends. There isn’t really a dysfunctional member, like one guy doesn’t show up one night or is in trouble with drugs or whatever. Everyone really wants to take care of the music, ultimately. Everyone can get in their own spaces; we’re different enough that we don’t smother each other.

This is our music and we share it, and we know we want to do a good job. That helps you in the moments where you’re tired or whatever—you know at least these guys are gonna throw down tonight. It’s like, “I disagree with you about that record you’re making fun of!” and then later that night they’re playing some incredible stuff and you just look over and smile and go, “Man, this guy’s got my back.” Advertisement

Photos by Cameron Wittig.