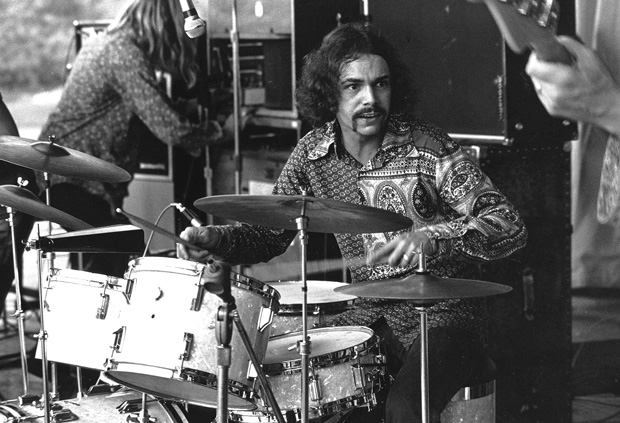

Danny Seraphine <br>Ready For the Next Phase

by Jeff Potter

Danny Seraphine fueled a long list of classic tracks in his twenty-three years as a member of Chicago, inspiring generations of drummers in the process. Since returning in 2006 from a long performing hiatus, he has been grooving in peak form with his current band, CTA, as heard on its latest CD, Sacred Ground. Also recently hitting the shelves are Seraphine’s autobiography, Street Player: My Chicago Story, and instructional DVD, The Art of Jazz Rock Drumming. Danny is honored in Modern Drummer magazine’s Influences feature this month; here he expands upon some of the topics covered in that piece.

MD: You’ve influenced so many drummers, but who influenced you?

Danny: I learned from Gene Krupa, playing along with The Gene Krupa Story. I also played along with records like Cozy Cole’s “Topsy Part 2.” Then I really got into Buddy Rich and, later, Elvin Jones and Max Roach. For rock, I was influenced by Hal Blaine, and later Mitch Mitchell was a guy I really listened to a lot and could identify with—the way he would stretch out with Jimi Hendrix. And Dino Dinelli—I loved his playing and style on those early Rascals records. He had that real swagger.

I loved all of James Brown’s records, especially Live at the Apollo with Clayton Fillyau. Local Chicago funk drummers also influenced me, including a drummer named Dwight Kalb. He had such a great feel. I absorbed that, and I still hear that in my own playing. The “Make Me Smile” groove was a derivative of Dwight’s playing. It’s a groove I picked up in Chicago, and it’s still with me. It’s a part of me—I think it’s one of the better parts of my playing. It gives me the pocket that maybe a lot of chops players don’t have. Advertisement

MD: After your long absence from drumming, you rediscovered what it really meant to you.

Danny: First and foremost, it’s what God put me on earth to do; it’s my calling. To run away from your calling and what you do best for so long…it can be destructive. I always just had an empty feeling. When I play, I feel complete. And when I’ve finished playing I feel complete too. To not have that for so long, I was starved. I want to get out with CTA and spread the music even more, because it’s really a great band.

This band is a true force. Sacred Ground includes some of the best things I’ve ever played on. Unlike the first CD, most of it is original material. It represents the evolution of where we started with CTA—trying to reinvigorate and keep the jazz-rock genre alive, because it’s been badly neglected.

MD: CTA’s debut CD, Full Circle, included reworkings of Chicago classics.

Danny: Some of my CTA bandmates wanted to get away from it, but I embrace it. When I first left Chicago—when I was fired—I didn’t want anything to do with it. I just wanted to be left alone and do something else; I didn’t want to play. I was very bitter and disillusioned with the music business. It’s a very unfriendly, corrupted industry. They’re carnivores: They eat their own. But I’m very grateful for the great career I’ve had up to this point, and I have a lot more music left in me. Advertisement

MD: What were the greatest challenges in returning from the hiatus?

Danny: The physical endurance part was one challenging factor. My confidence was another. That took a while. The Modern Drummer Festival performance of 2006 was a really big thing for me. It was like the drummers of the world welcoming me back, embracing what I’ve done. It made me realize that people hadn’t forgotten me and that I had a lot more to contribute. It was a great, great night for me that I’ll never forget.

The drums are the most physically challenging instrument by far, especially if you play double bass drums. And I love that part of it—keeping in shape, staying healthy. At sixty-five, that can be very challenging. Things do wear out. [laughs] I’m dealing with some ailments; age takes its toll. Nonetheless, I’m going to play until I can’t play anymore. Every drummer that I know close to my age is having physical problems. For example, if you’re playing matched as opposed to traditional grip, you’re going to have troubles in your forearms rather than under your thumb, where you hold the fulcrum in traditional grip.

MD: Has alternating techniques helped minimize the repetitive stress?

Danny: Yes, definitely. I’ve always switched grips, even several times within a song. I love traditional grip. I love the fact that my left hand sounds different from my right. Some people strive for the hands to sound exactly the same with matched grip, but I like the different colorations that you can do with your left hand. It’s important to have traditional grip in your arsenal. It’s a whole other range of colors in your palette. Advertisement

MD: What’s next?

Danny: I feel like I’m about to go into another phase. That’s the great thing about drumming and all music: It’s ever-changing, and there’s always something to learn from someone else. It’s beautiful that, as drummers, we openly share licks and grooves. Each of us has our own DNA, our own stamp on the music. Someone could try to play “Make Me Smile” the same way, but it’s just not going to be the same, and vice versa for me trying to play a Buddy Rich or Mitch Mitchell thing.

It’s a great thing about what we do, the realization that our licks and grooves are just passing through us. Yeah, we might be known for them, but I got my influences from other people, and I’ve influenced a lot of drummers in turn. It’s a gratifying thing when someone says to me, “I started playing because of you.” It makes it worthwhile and gives me fuel to keep going, keep getting better, keep my playing young.

Photo by Tom Copi.