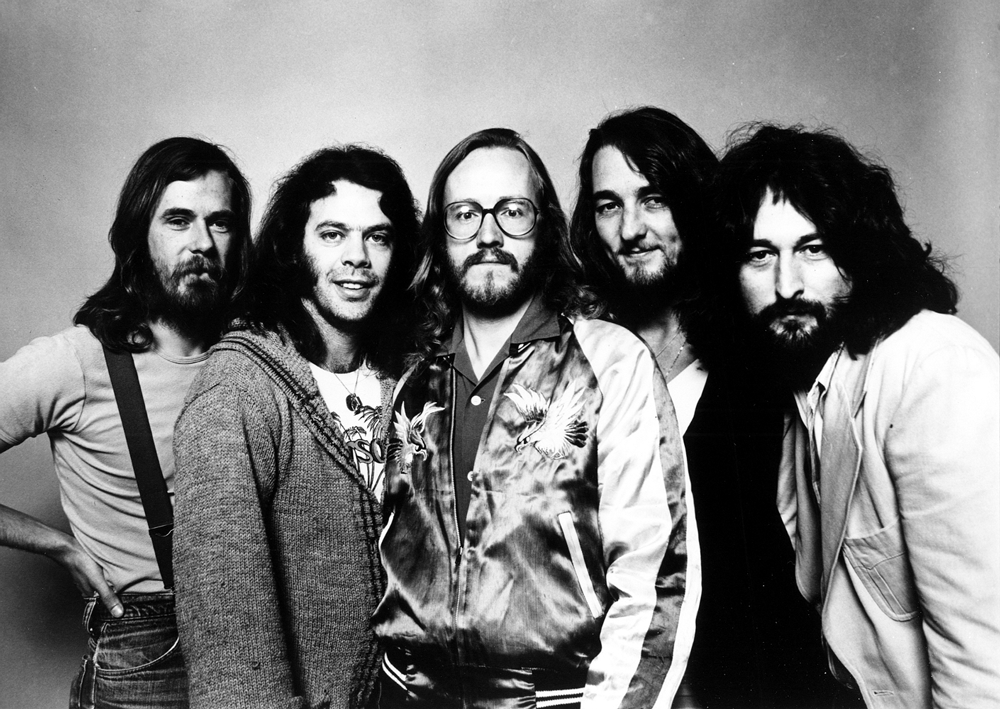

Supertramp’s Bob Siebenberg

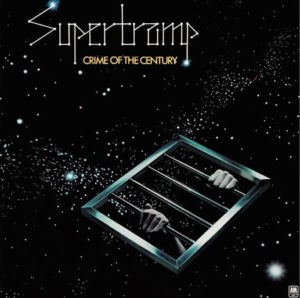

Reflecting on the fortieth anniversary of the band’s classic Crime of the Century album

by Adam Budofsky

Supertramp has always been tough to categorize. Is it a pop band with a fondness for complex arrangements, a progressive-rock band with impeccable pop smarts, or something else entirely? One thing’s for sure: Difficulties categorizing the group seemed not to hurt its popularity, as a string of hit albums, including Even in the Quietest Moments (featuring the hit “Give a Little Bit”) and Breakfast in America (“The Logical Song,” “Take the Long Way Home,” “Goodbye Stranger”) kept Supertramp at the top of the charts throughout the mid and late ’70s.

The group’s breakout album, 1974’s Crime of the Century, has recently been remastered and fleshed out with a second disc containing a 1975 concert at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, mixed from the original tapes by on-the-night engineer and regular Supertramp studio guide Ken Scott, who’d previously worked with the Beatles, David Bowie, and Mahavishnu Orchestra, among many others. Modern Drummer asked drummer Bob Siebenberg—whom Supertramp followers know from album credits as Bob C. Benberg—to reminisce about the recording, which still sounds remarkably vital today.

MD: It’s difficult to avoid superlatives when discussing Crime of the Century. The songs, the sounds, the performances, and the ideas are all so strong. At the time did you feel that you were on to something special and making a leap forward as a band?

Advertisement

MD: It’s difficult to avoid superlatives when discussing Crime of the Century. The songs, the sounds, the performances, and the ideas are all so strong. At the time did you feel that you were on to something special and making a leap forward as a band?

Advertisement

Bob: The band was brand new. [Singer-songwriters] Rick Davies and Roger Hodgson had recorded two albums previously with two different lineups, without much success. There was a real feeling of optimism in the new lineup, and we jelled right away. We knew we had an interesting cast of characters and totally believed in ourselves. This was the first record with the new lineup, and it felt like we could do something special. The ingredients were all there. We had label support and tons of enthusiasm.

MD: Your playing is always graceful, yet your parts are often unexpected. The main drum beat of “Dreamer,” including how it sort of slips in during the buildup, is not typical. The removed backbeats in the verses of “Bloody Well Right” are really cool. The floor tom and delayed-snare bit in “Hide in Your Shell,” the offbeat cymbal crashes during the dual-vocal section of “Rudy,” those big flammed fills when you enter the title track—so many cool approaches. Did you make a habit of trying significantly different ideas when you were arranging your parts in the studio or rehearsal room?

Bob: Thanks for saying so. I appreciate it. The drumbeat in “Dreamer” evolved from an idea by Roger. He always had unorthodox ideas about drums, and sometimes it would turn out really cool. These ideas would get sent through my filter and feel and come out the other end. What you mention on “Bloody Well Right” was just how I heard it. It followed the feel of the riff. And, yeah, I was always in pursuit of being creative and solid. My job was to provide a steady but interesting backbone. If it didn’t need a fill, don’t do one; the transition setups could be served by just an extra bass drum kick or flick of a stick. If it needed a fill, make it count. Make it meaningful and keep the pulse seamless. Advertisement

All these examples you have chosen came pretty naturally. It’s always a process of simplifying, listening back and deciding whether it was cool or not. It starts in rehearsal. We used to tape our rehearsals on a two-track and sit and listen and find the form. Things would evolve right through the backing-track stage in the studio. Once we get in there and hear the sounds, things can change.

The “Hide in Your Shell” piece you refer to was a production idea. By that I mean it’s not what I originally started to play. Roger and Ken pulled that one out on a particularly zany night. I’m [actually] playing it pretty straight in there. It’s a cool beat that sits up and hovers and always sits back down on the 1.

Supertramp in the early ’70s, featuring, from left, bassist Dougie Thomson, drummer Bob Siebenberg, sax/woodwind player John Helliwell, singer/guitarist Roger Hodgson, and singer/keyboardist Rick Davies

Advertisement

MD: There’s such clarity to your stick work. Did you have rudimental training when you were coming up?

Bob: I would have to admit I’ve had no rudimental training. It’s all seat of the pants. It’s how I learned to play—listening, emulating, and feeling. I grew up playing in bands. I never lived anywhere where I could practice.

MD: More than many drummers, you really work the floor toms into your creative ideas. The fills leading into the choruses of “Asylum,” for instance, are so powerful. And the way they’re treated with reverb there makes them sound even more dramatic. One could imagine these types of moments being the result of discussions between the band and Ken Scott. Was that the case?

Bob: Well, to begin with, we were so fortunate to have Ken at the helm. There was and is no one better in the studio as a producer/engineer than Ken. And that’s not to take anything away from our good friend and producer/engineer Peter Henderson, who we worked with on several records later in our career, including Breakfast in America. But it was a different time and stage in our career with Ken. He was totally absorbed and working hard to create something that would blow people away. He set the tone for what our records had to be for the rest of our career. Advertisement

In the case of “Asylum,” those were the fills I had cooked up in rehearsals and modified ever so slightly in the studio. Ken recorded them and made them sound the way they do. There was always interaction between us in the studio. We were all in this together, and we had respect for one another and were all willing to take direction. Ken included.

MD: The sound quality of Crime is as good as anything being released today, forty years later, and it seems to really benefit from a spaciousness in the mix. Do you recall any details about the recording in terms of miking or mixing?

Bob: The arrangements to these songs are very streamlined and very well thought-out. Rick and Rog were totally absorbed in the process—as we all were—but these were songs they’d been cooking up for quite a while, and they had a pretty good idea how they wanted them to come off. As for the mixing, it was an all-hands-on-deck affair. Everyone had a job to do. All pre-automation, pre-digital—totally handmade. Advertisement

MD: Do you recall what gear you used on the sessions?

Bob: I had brought over my drums from Los Angeles when I moved to London in 1971. [Siebenberg, the lone American in Supertramp at the time, had previously played with the popular British pub-rock band Bees Make Honey.] I had bought them in 1965. They were champagne sparkle Ludwigs. I used a 26″ Ludwig bass drum, with two on the top, one on the floor. I had picked up a Rogers 16×18 in London. My snare drum was a wooden Gretsch.

My cymbals were pretty raggedy from years of dragging everything around, and they were all Zildjians except for the main ride, which was a Zyn I had picked up somewhere while playing in Bees Make Honey. All of them except for the hi-hats were replaced after recording the album and there were a few bucks around to hit the road.

MD: Several of the tracks on Crime have dramatic drum entrances, sometimes a couple minutes after the song begins. When you play those songs live, are you really raring to go as the tension builds up to those entrances? Advertisement

Bob: Well, yes, I guess you could say that. Being on the stage with Supertramp back then was a totally focused affair. I was always listening and inside the tune. I would start playing along in my head as my spot approached, and my body would start to move as if I was already playing, and bang. So I was totally in before I actually started. It’s a great band to play in. The band was always very, very focused on the music.