AUDIO DEMOS: Creative Compression Techniques: 4 Ways to Pump Up the Excitement in Your Drum Tracks

This excerpt is taken from the complete article that appears in the September 2015 issue,

which is available here.

Electronic Insights

Creative Compression Techniques

4 Ways to Pump Up the Excitement in Your Drum Tracks

by Mark Parsons

If I were limited to a single tool for processing drum tracks, I’d pick the compressor over equalizers, reverbs, gates, delays, and other effects. There’s so much that compressors can do to tame, tighten, or just plain twist your performances. Yet I often see drummers avoiding them, unsure of how to best use compression to improve their recordings.

At its most basic, a compressor is a device designed to limit the dynamic range of the signal passing through it. It was originally used as a utilitarian tool to prevent the music from overdriving the tape. But engineers soon realized compressors could do more than just control levels for technical reasons, and they began to use the devices creatively, to change the sonics of their tracks and add a feeling of energy and excitement. Let’s take a look at some different ways to use compression on drums, both in an everyday fashion and for more adventurous sounds.

Serial Approach

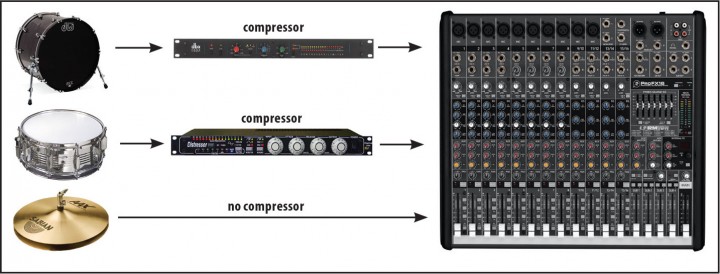

Serial compression simply means you’re processing the entire signal. To get a feel for how this works, add a compressor to your snare track and dial up the different parameters. You’ll want to experiment, but good starting points might be a fairly fast attack (around a millisecond), a fast release (100–200 milliseconds), and a medium ratio (4:1). Pay close attention to the processed signal, and gradually lower the threshold (the control that determines how much compression you’re applying). Listening for how the leading edge of the attack pops up and is followed by the compressor clamping down on the signal to give you a fuller, fatter, longer fundamental sound. Lower the threshold until you get a sound that excites you. Once you find the tone you want, add make-up gain to get the level back to where it belongs. (Part of the magic of compression is that it allows you to raise the perceived volume of the signal, because there’s less discrepancy between the peak and the average level.) Advertisement

You can apply the same methodology to your kick drum signal. You may end up with slightly different settings and perhaps less overall compression than you used on the snare, since you’re looking to retain more of the point of the beater attack while keeping the boom under dynamic control, in order to get a punchier and more consistent sound.

In the demo below, you first hear the dry (uncompressed) signal, then with the kick and snare compressed, and then in a mix with other rhythm instruments.

Parallel Chain

This technique has been around for a while but is becoming more and more popular, especially in harder-hitting situations. (Parallel compression was once called “New York compression,” as it was used famously by East Coast engineer/producers like Ed Stasium, who worked on Living Colour’s Vivid, among many others.) Advertisement

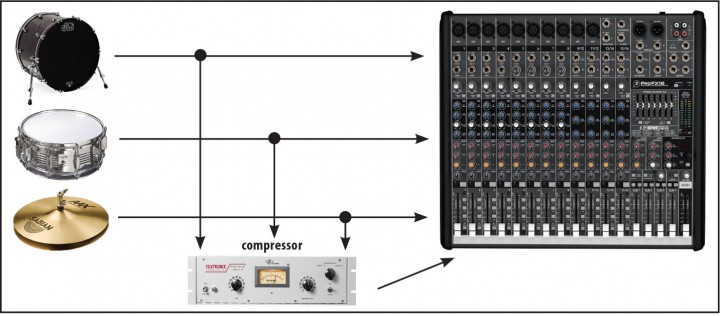

In parallel compression, you’re sending some of the signal to be processed (compressed) while leaving some of it untouched. You then blend the wet signal with the dry to taste. The advantage of parallel compression over serial processing is that you’re able to retain the original dynamics of the uncompressed signal while also being able to add the fuller, fatter sound of the compressed transients. This allows you to have an infinite variety of choices between a fully realistic and a completely crushed sound, while maintaining the best qualities of both.

There are multiple ways to accomplish parallel compression. If you’re working in a computer, you can simply clone the parts you want to parallel process, squash the cloned parts with a compressor, and combine that with the dry tracks. Another option is to set up an effects channel with a compressor, buss your tracks over to be compressed, and use the effects-channel fader to blend in some of the effected signal.

Regardless of which technique you use, the overall methodology will be a little different from using serial compression. When you adjust the amount of compression on the wet side of the equation, you’re looking for qualities that—when added to the dry signal—will yield the overall tone you’re after. This means that instead of going for a moderate amount of compression, you may choose to go for a seriously slammed sound to blend with your dry tracks. Advertisement

The demo below demonstrates parallel compression. First you’ll hear the dry signal, then just the highly-compressed signal, then the dry signal blended with the compressed signal, and then in context.

Squashed Room Mic

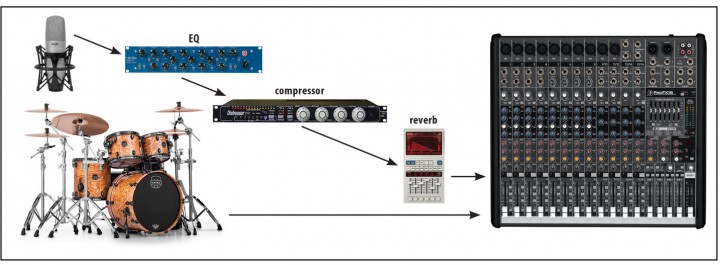

Among other things, compression brings down the transient (initial drum hit) in comparison to the sustain. Bringing up the shell tone on a close-miked drum can thicken a snare, for example, but if you want to have the room itself come up in the mix after the initial note, the best way is to apply compression to a room mic so that the room “blooms” after the initial strike. This will make your room sound much bigger and energetic—it’s one of the secrets to the coveted Led Zeppelin drum sound.

Experiment with the mics you have available, but I’d ultimately recommend using a large-diaphragm condenser or a ribbon mic. Walk around the room and listen while someone else plays the drums. You’re looking for a spot where the reflective buildup is prominent. Place the mic there, and track it along with your usual close mics and overheads. Advertisement

Slam the heck out of the room-mic signal, and then add that to your overall mix as a spice. The difference between this and the methods already discussed is that the room-mic compression will sound almost like adding a special kind of reverb to the mix that ducks down the instant a drum is hit and then adds some boom as the room rings. If you tweak the attack and release settings a bit, you can even get the compression to pump in time with the music.

The demo below was made using just three mics on the drums (Glyn Johns arrangement in a fairly lively room) plus a mic placed across the room, with no reverb on any of the drum tracks. First you hear just the dry three-mic arrangement, then just the compressed room mic, then a blend of the dry with the compressed room, and then all mics in context.

For more on this topic, including how to tweak the tone using EQ and reverb, check out the complete article in the September 2015 issue, which is available here.