Vic Firth: 1930 to 2015

Vic Firth

Modern Drummer was saddened to hear of the passing of Vic Firth. The following profile on the performing and manufacturing giant, written by Lauren Vogel Weiss, first appeared in the July 2013 issue of Drum Business magazine.

Careers in the music business can be fleeting, so to have one last for fifty years is quite a milestone. But to have three jobs in music, each one lasting half a century, is truly remarkable. Add to that first-name, worldwide recognition, and you’ve got someone very special. Drum Business takes a peek behind the curtain with a well-known name in the music industry: Vic Firth.

Born in 1930 in Winchester, Massachusetts, eight miles north of downtown Boston, Firth has been a performer, teacher, and successful businessman in music for more than sixty years. From his five-decade career with the world-renowned Boston Symphony Orchestra, to his years teaching at the New England Conservatory of Music (his alma mater), to the 2013 celebration of fifty years manufacturing drumsticks, Vic still reports to the office on a daily basis, running one of the most successful percussion companies in existence. His dry wit and New England practicality have served him well throughout his career. Advertisement

From Jazz to Classical

Raised in Sanford, Maine, in the southwestern corner of the Pine Tree state, Everett Joseph Firth grew up in a musical family. His father was a trumpet player who taught music in five different schools. The younger Firth started his musical journey on the cornet at the age of four, even though his father had wanted him to play French horn. “By the age of ten, they decided that my embouchure was such a total failure that we’d better look in another direction,” Firth recalls.

“My father had worked in California doing arranging, and that’s what he thought I should be thinking about,” Vic continues. “So I took a theory lesson, a piano lesson, a clarinet lesson, a trombone lesson, and a drum lesson every week, just to get some background—and I loved it! It wasn’t like it was work. I never did anything that wasn’t fun, and those lessons were fun. That’s how I got started musically: in a diversified way.”

Young Firth played a little bit of everything, but soon his talent surfaced in percussion. He played snare drum in the Sanford High School marching band and timpani in the concert band. “There was no orchestra in those days,” he explains. “The high school was made up of about 500 students, and my dad was the band director. He had 125 in the band, which is a credit to my father.” Advertisement

By the time he was fifteen, Firth had formed his own twelve-piece band…and had begun playing under the name Vic. “‘Everett Firth’ sounds like a skin disease,” he says with a laugh, “whereas Vic Firth was a little bit easier to pronounce and print. I wanted a name that would fit the band business. I booked the band all over New England playing dances, and I also had a seven-piece group for smaller occasions. I was very active in the jazz business—that’s where I started out, and that’s where I thought I was going. But I took a wrong turn when I was at the Conservatory!”

Firth performing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the 1960s

Firth had been studying percussion with Salvy Cavicchio in Maine. While still in high school, Vic began making a six-hour round-trip drive to Boston to study snare drum with George Lawrence Stone and keyboard percussion with Larry White, who was teaching at the New England Conservatory at the time. (Although White influenced Firth to pursue his studies at NEC, he left Boston before Vic began his freshman year.) During his second year at the Conservatory, Firth received a scholarship to go to the Tanglewood Music Festival in western Massachusetts, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. “I suddenly saw all this music that I had never heard before,” Firth explains. “I was very taken with it and loved it. So I focused all my time and energy on playing classical music and learning the repertoire.” Firth supplemented his musical education with biweekly trips down to New York City, where he studied timpani with Saul Goodman.

“I started out in music education, because I thought it would be a good insurance policy to have, not knowing where I would go and how fast I’d get there,” Firth continues. “But by the second year, I became a full-time applied major. If I didn’t do an eight-hour day of practicing, something was wrong. I could play more with one hand than I do with two hands now! I worked really hard five days a week and then took the weekend to raise hell. The day before I auditioned for the symphony, I played nonstop for fourteen hours.” Advertisement

At the tender age of twenty, Firth auditioned for maestro Arthur Fiedler and joined the Boston Pops Orchestra. One year later, he auditioned for the conductor of the Boston Symphony, Charles Munch, and joined the BSO in 1952—while he was still a student at the conservatory. “I was the youngest player in the orchestra for about seven or eight years,” Firth recalls. “I joined as a percussionist and worked my way up. Roman Szulc [who also taught at NEC] was the timpanist before me. He made a wonderful sound on the instrument, but when it came to 5/16, he always made it into 6/16. He couldn’t do the contemporary music and asked me to play this piece and then that piece. I soon ended up playing timpani on everything unless they needed a full percussion section. So every door that could possibly open was opened for me, and I was prepared to go through it. I had more nerve than brains in those days!”

Firth was promoted to associate principal, then assistant principal, and finally, in 1956, he earned the coveted position of principal timpanist in the Boston Symphony, a position he held until 2002.

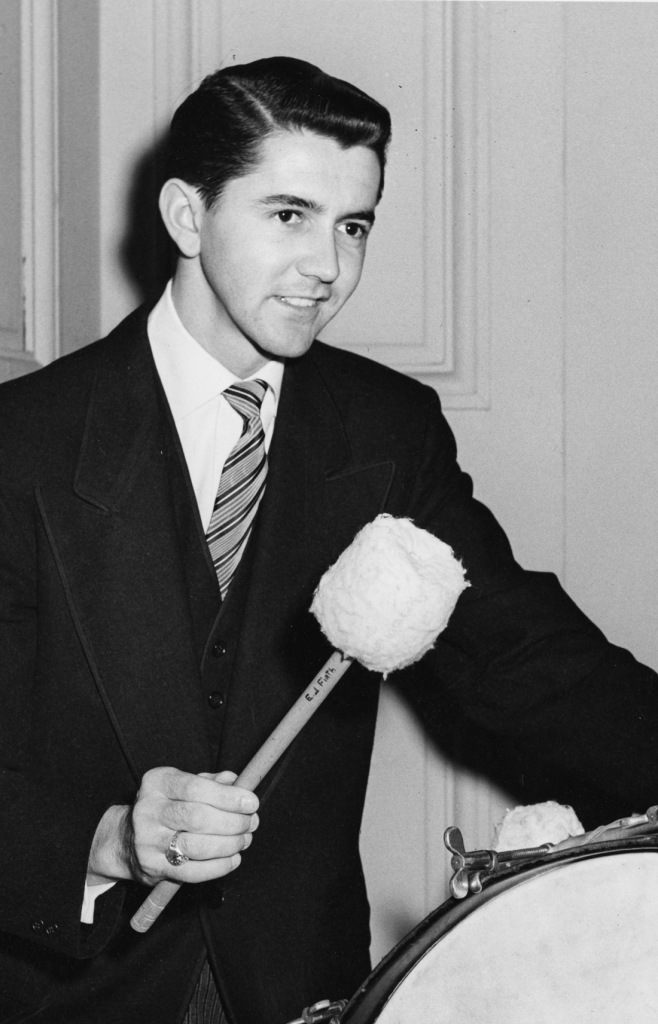

Vic played snare drum in the Sanford High School marching band in Maine in the mid-’40s.

Timpanist and Teacher

Firth performed with the BSO for fifty years, which adds up to approximately 10,000 concerts. “Fifty years is a nice round number,” Vic says with a smile. When asked to name a favorite concert or composition, he demurs. “I had such a long stay with so many great moments, it’s hard to single out any one thing. And there are so many great pieces of music. It’s hard to pick out just one. There were great composers from all the different periods, and I enjoyed them all.” Favorites range from Beethoven (all of his symphonies) to Bartók (Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta) to Stravinsky (The Rite of Spring).

Besides performing all the great orchestral literature of the past three centuries, Firth has worked with some of the world’s most famous musicians. “I’ve played with all the greats,” he says, “including [Jascha] Heifetz, [Gregor] Piatigorsky, [Arthur] Rubinstein, [Vladimir] Horowitz…and the list goes on. The conductors have been [Leonard] Bernstein, Colin Davis, [Leopold] Stokowski, [Eugene] Ormandy, [Serge] Koussevitzky…. It’s like I’m making up a who’s who—how could one person have possibly played with all of those great names”? But he has. Advertisement

Firth in 1952, his first year with the Boston Symphony Orchestra

“I’ve probably played in all the best concert halls in the world several times,” Firth says. “But the best hall in the world is Symphony Hall in Boston!” Modeled after the Musikvereinshaus in Vienna, which seats about 1,700, Symphony Hall has room for about 900 more people. “It’s a magnificent piece of architecture to perform in,” Vic says. “And the other one is in Vienna. Those are the two top halls in the world.”

Another of Firth’s favorite composers is Johannes Brahms. “The first symphony that I played with Boston was Brahms’ Second [Symphony],” he remembers. “It was my first year in the orchestra. During my fiftieth year in the orchestra, we were on a tour of Europe with [conductor] Bernard Haitink, and we played Brahms’ Second. I opened with it and closed with it. And it was just as exciting and thrilling for me to hear it and play it fifty years later as it was the first time. I had a passion for great music and found a great deal of enjoyment from playing it—being part of producing what was on that printed page.

“When I joined the BSO,” Firth says, “it was the golden years of symphonic music. There were fewer people who auditioned, but the standards were much higher. It’s tough for young players today. There are more talented players out there but the same number of jobs that there were fifty years ago.” Advertisement

In 2002, Firth retired from the Boston Symphony, finishing an impressive half-century career with one of the world’s premier musical ensembles. “My dear friend Bob Zildjian used to kid me that the only reason I stayed was because I couldn’t get a job anywhere else,” he says, laughing. But throughout his tenure with the orchestra, Firth walked down the street from Symphony Hall to teach at the New England Conservatory of Music.

Even though he graduated from NEC in 1952, Firth had joined the faculty two years before, first as a teacher in the preparatory department, then as head of the percussion department. He also taught for years at Tanglewood, the same music festival that so influenced his own career in music. When asked to name some of his former students who have gone on to successful careers in the music business, Firth shrugs off the question and dryly quips, “I have students all over the world. So everywhere I go there’s usually somebody there at the airport to pick me up. If I had known that, I would have taught more students!”

Firth was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree—given to individuals who have made significant contributions to the world of music—by the New England Conservatory in 1992, four decades after he received his bachelor’s degree from the acclaimed school. He also holds honorary doctorates from the University of Southern Maine and the VanderCook College of Music. Advertisement

Teaching led Firth to compose more than two dozen works, including popular etude books and ensembles. Students have been performing his solos for decades, and excerpts from his books The Solo Snare Drummer and The Solo Timpanist are still on All-State audition lists across the country. Published by Carl Fischer in 1964, his “Encore in Jazz”—a percussion septet scored for timpani, three snare drums, vibraphone, marimba, bongos, congas, and “dance drum setup”—was one of the first pieces to incorporate jazz into a percussion orchestra format and is still performed by high school and college ensembles today.

Vic inspecting drumsticks at the factory in 2003

Sticks, Mallets, and More

It’s hard to believe in this era of Internet access and overnight delivery that there was a time when finding high-quality percussion implements involved more than a phone call or Web search. But in the 1950s, there were only a few manufacturers making sticks and mallets, and the quality was not always up to the standards of say, the Boston Symphony. “I needed some good sticks for myself,” Firth says, “as well as for my students at the conservatory.” So he designed two models of snare drums sticks—the SD1 General and the SD2 Bolero (with a smaller tip)—and had them custom made by a wood turner in Montreal.

“The orchestra was on tour in Chicago in the early 1960s,” Firth recalls, “and I went to Frank’s Drum Shop. [Owner] Maurie Lishon said, ‘I understand you’re making drumsticks.’ I told him I wasn’t making them for sale, but if he wanted some, I would order an extra dozen for him. Three weeks later he called up and asked for two dozen. And that’s how it began. Advertisement

“Then I started making timp sticks,” Firth continues. “I started off with six or seven models. Then I started to branch out, because I was playing so many contemporary pieces with the chamber music group. I needed things like double-headed sticks, and there were no commercial sticks available. Rather than complain about it, I decided to design some sticks and make them myself, for myself. Well, it grew beyond my wildest dreams. I just tried to make a quality product that I knew drummers would find musically gratifying to play with, and from those twelve pair a week, we now make 80,000 sticks a day in two shifts. How I ever got involved in this is beyond me! But it’s been a great ride.” The Vic Firth company is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary in 2013, yet another milestone for the New England timpanist.

Firth still remembers those early years. “I didn’t formalize anything,” he says. “Everything was done with a handshake, and that’s the way I’ve run it until recently. I was the first one to start rolling sticks and guaranteeing them to be straight. One of my competitors told me I was crazy and was going to ruin the business. ‘You can’t guarantee a piece of wood to be straight, because Mother Nature has a say in it!’ All you do is roll them, and the ones that aren’t straight, you burn them.

“The second thing that I did that turned everybody back on their heels was the pitch pairing,” he continues. “One day, I dropped a bunch of sticks on the floor and it sounded like a xylophone in the high register—all those different plink, plank, plunks. So I sat on the floor, tapping the sticks, and realized that if both of them had the same pitch, they had the same weight and felt the same—and when you struck any surface, they sounded the same. Everybody thought I was nuts. But it turned out there was a lot more to it than we imagined. Today, everybody has to do something to that effect, or you don’t have a pair of drumsticks that are matched.” Advertisement

Today, Vic Firth the company manufactures more than 350 products for drummers and percussionists, ranging from signature drumsticks to marching mallets to hearing protection. Its website, vicfirth.com, is one of the leaders in the industry, emphasizing education. “One of my best talents is being able to pick good people,” Firth says, singling out director of Internet activities Mark Wessels and integrated media marketing manager Andy Tamulynas for their outstanding work on the site. “When I started the business,” Vic recalls, “the right people were just those who were dedicated and sincere and would do the job correctly. Now it’s so technically involved, it goes beyond the jobs I hired people for then.”

Although Firth’s two daughters, Kelly and Tracy, worked in the family business for years, neither of them wanted to take over the company. “Since I had lots of pursuers offer to buy it, rather than just let it go wherever, I picked Zildjian,” Vic says. He describes their 2010 merger as a “good romance.” “And it’s been very successful too,” he adds. “We work with complete autonomy. I run their business the way I used to run my business.” Firth continues to serve as president, attending meetings, visiting the manufacturing plant, and appearing at conventions and trade shows…all well into his eighth decade.

In addition to his successful percussion company, Firth has dabbled in several other ventures. “What you don’t know is that I also ran an art gallery specializing in American paintings and American clocks,” he says with a grin. “And I was a partner in a closed investment partnership. People don’t know about this side of me, because I kept it away from the other business.” Advertisement

One of his sideline ventures that the public may be more familiar with is the Vic Firth Gourmet division. “I bought a new plant to manufacture sticks in the mid-’90s,” Firth explains. “With that factory came a number of businesses, including a gourmet division. The pepper mills were so beautifully designed. I knew nothing about the market, nothing about the players, but I started applying the things that I learned with the drumsticks to the pepper grinders. I immediately got some signature chefs, Mario Batali being one of them, and added a lot of new shapes. It was kind of a diversionary strategy, and it was fun. I took great pride that we made the best pepper grinder and pepper mill in the business. But I recently sold that business to some other Maine folks, so I’m no longer in the pepper mill business.”

Kenny Aronoff wearing Vic’s tie, and Vic wearing Kenny’s glasses, in 2000

Percussion Perspectives

How did Firth juggle playing in the orchestra, teaching at the conservatory, and running the business? “I was a workaholic,” he says. “I didn’t know any better. Everybody said, ‘You’re crazy. How can you do all that?’ The symphony job was number one—you had to have your brain sharp and your wits about you to do a perfect performance every time you played—but I thrived on doing everything. You have to have the energy and enthusiasm to do it…and I did.”

In addition to his “day jobs,” Firth also served the Percussive Arts Society for a long time. He was on the board of directors for sixteen years (1984–1991 and 2004–2011) and held the position of treasurer for four years (1987–1990). He was also a member of the PAS Sustaining Member Advisory Council from 1994 through 1999. In 1995, PAS inducted Firth into its hall of fame at its convention in Phoenix, Arizona. Firth has also been honored with the Modern Drummer Editor’s Achievement Award and the Music & Sound Retailer Lifetime Achievement Award. Advertisement

With so many years in the music business, how does he view the current marketplace? “The percussion industry has grown and expanded in the last twenty years, to where it’s gotten very competitive and very crowded,” Firth says. “Unfortunately, I don’t think the music business itself is expanding enough to accommodate all these new manufacturers. I see some rough sledding and competition ahead for everybody. Those that succeed will get stronger, and a lot of the weaker ones are going to go down. So it’s going to be a tough battle for manufacturing in this country.”

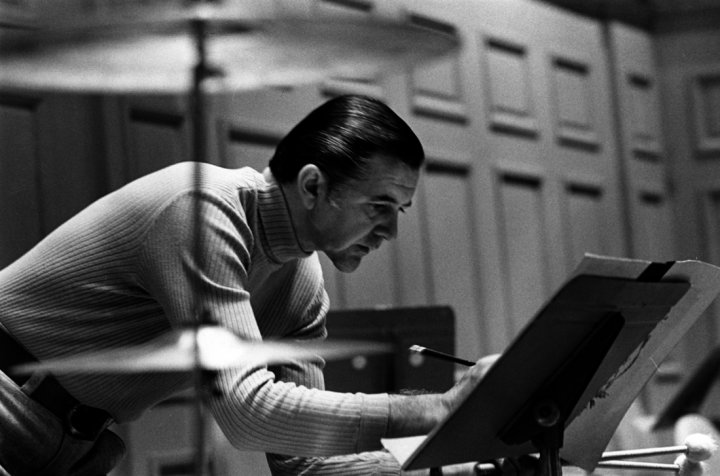

Firth at a rehearsal with the BSO in the ’70s

How would he predict the future for his namesake company? “I see Vic Firth constantly expanding,” he says. “We’ll continue to be the leader in the quality of the products and setting the standards for all of us. That’s the way we all think around here. Right now we’ve got a list of new products that we’re working on that fills a typewritten page.”

As Vic Firth the company looks ahead to the next fifty years, Vic Firth the man looks back on a wonderful career in percussion. “People ask me how it feels to see your name on so many sticks,” he says. “It doesn’t really do anything to me one way or the other. I thought maybe I could contribute something to improving mallet or timpani technique. Since I had all this playing experience, why not put it to somebody else’s use? That’s why I did it. I would like future generations to think of me as someone who was musically equipped at the highest standards. The same standards that applied to anything I did relate to music and musicians.” Advertisement

Even though he doesn’t like to admit it, Firth has left an indelible imprint, on both music and the music industry. What does he think will be his lasting legacy? “Probably my contribution to the Boston Symphony,” he says humbly. “And…that I was a character!” Vic’s laughter fills the room.