Faith No More’s Mike Bordin Discusses Sol Invictus and His Hard-Hitting Playing Style

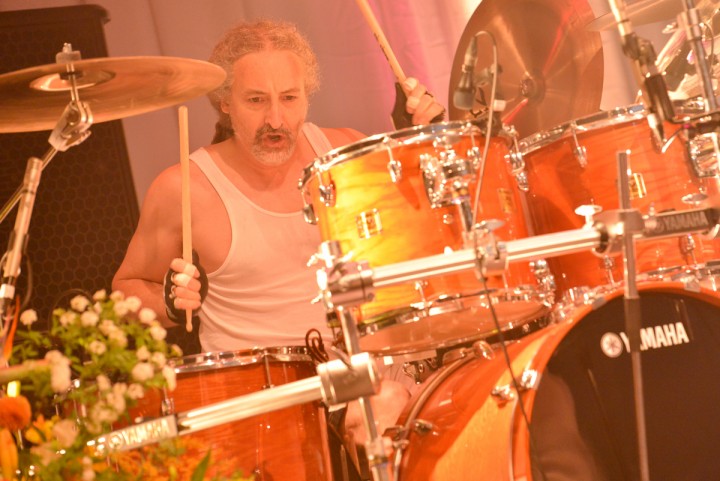

Photo: Ross Halfin

by David Jarnstrom

Any respectable list of the hardest-hitting drummers of all time simply must place Mike Bordin at or near the very top. Even at fifty-two years of age, the dude is an absolute warrior—an imposing pile of dreadlocks draped down his back, flexed arms ever uncrossed for maximum clearance and velocity, batting gloves gripping tree trunk–sized sticks, butt ends raised to the sky. His kit, too, looks like it was built for all-out battle. Massive ride and China cymbals tower to the left of a metallic tank-like snare, while perfectly flat, impossibly deep tom-toms sprout upward from a cannon of a kick drum. Most drummers tape their set list to their hi-hat stand. Bordin tapes his to the inside of rack tom number two—and his bands play a lot of songs, you dig?

Bordin not only drums with otherworldly levels of power and intensity, but also an understated and utterly unique sense of musicality, stemming from his myriad influences and distinct approach to the kit. A southpaw playing open-handed on a right-handed setup (sans the aforementioned cymbals), Mike was reared on punk and metal, but made his bones dishing out devastatingly deep grooves that, paired with manhandling bassist Billy Gould, would come to define the elastic yet airtight foundation for Faith No More, one of the alt-rock era’s most stylistically ambitious and inimitable groups.

Best known for their smash hit “Epic” from 1989’s breakthrough album, The Real Thing, Faith No More would prove over the ensuing decade to be so much more than a passing funk-metal gimmick. The versatility of vocalist Mike Patton—anchored by the pop sensibility of Gould and keyboardist Roddy Bottum—emboldened the Bay Area quintet to spread its wings and experiment voraciously. Subsequent releases Angel Dust (1992), King for a Day…Fool for a Lifetime (1995), and Album of the Year (1997) found Faith No More blurring the lines between disparate genres with cocksure aplomb—and complete irreverence to a mainstream music industry that hadn’t a clue how to market them. Advertisement

And while Bordin lived out his childhood dream playing sideman to Ozzy Osbourne in the decade-plus following Faith No More’s seeming late-’90s demise, there’s little doubt that FNM is the band in which he was born to bash. For proof, listen no further than Sol Invictus, the band’s shockingly superb reunion record, and their first new material in over eighteen years. From the no-holds-barred bombast of “Superhero” and soul-soaked odd time of “Sunny Side Up,” to the operatic grandeur of “Matador” and campfire Kumbaya of “From the Dead,” Bordin and company have seamlessly updated their mutant strain of hook-laden hard rock for the new millennium, and have been hard at work spreading their gospel to the worldwide masses all summer.

During an all too brief tour break, Bordin took a moment to talk to Modern Drummer about why Faith No More got back together, the DIY ethos that drove the making of Sol Invictus, how he manages to deliver such a physical set every night, and much more.

MD: Sol Invictus sounds so organic and inspired—the music doesn’t feel forced, like reunion records often do. It’s familiar in the sense that it sounds like Faith No More, but it’s clear you weren’t deliberately trying to replicate anything you’ve done in the past. Advertisement

Mike: Well, it was made for the right reasons. If we were struggling or stressed or grabbing at straws—well, we wouldn’t have made it in the first place. But if we had, it wouldn’t have been this. It wouldn’t have been, as you say, organic or unforced. And that was very important to us. It sounds kind of cliché, but we’re really trying to keep it clean and focus on the music rather than all the other stuff that bands can get sidetracked with.

MD: What was the impetus to get the band back together for the Second Coming Tour back in 2009?

Mike: Our manager called the core of us together and said, “Look, there’s a lot of people who are interested in seeing Faith No More—have you guys considered it”? Every one of us had a job, and I mean that in the best possible way. I was playing with Ozzy, Mike has a million bands, Roddy has Imperial Teen and he’s scoring films and TV shows, Bill is playing in bands and producing records. So honestly, we’d never even considered it. Everybody was pretty good with where they were, but that definitely got the conversation started.

We didn’t have a big plan. We just got together in a rehearsal room and it felt good, so we did some shows. And when the shows started getting into the couple dozen, and the band started getting pretty strong, we were like, “Okay, now either we’re done, or we’re going to have something else to say.” Because if you don’t have something new to say and you just keep carrying on, it becomes nostalgic. Nobody was here to do nostalgia. No one was here to recreate a time when we had less gray hair and more brain cells, you know? [laughs] Advertisement

So new music came. It came honestly, it came gradually, and in my opinion, it came correctly. A lot of people will do it the opposite: “Well, you’re doing a reunion tour, you’ve got to have a new album to promote.” But if you haven’t played together in fifteen years, how the hell are you supposed to be comfortable with each other? We have our own language and it’s not only musical—it’s emotional and physical, as well. It’s a unique thing and we had to give it time to work. And that’s what happened. It’s been a crazy, cool gift to have a second chance to do this again with more experience and more perspective under our collective belts.

MD: The physicality with which you play certainly hasn’t diminished.

Mike: I don’t think so, no. We play for real, you know? We know how to deliver live music in an energetic and compelling fashion. And we’re not too old to where we physically can’t do it. On the contrary, I feel I work smarter, which allows me to be even stronger than before. At my age and the amount of shows that I’ve done, I know when to push and when not to push. But I still give you everything I have, and I mean that. Every single thing I have every single night. That’s what I do. That’s my role and I’m very happy to do that. There’s no drug like it.

MD: Are you doing anything differently in terms of diet or exercise or routine to stay in shape these days?

Mike: Well, I’m not one to go out and go ape-shit crazy on tour. What I do is mentally and physically protect myself, because I know that I’ve got a show to do and that’s my focus. That’s my primary consideration, just making sure my batteries are charged up enough so I can drain them out completely at the show. And that’s never changed. It’s a lot of quiet time, it’s fluids, it’s eating well, it’s getting plenty of rest—all that stuff. Advertisement

MD: I always get a kick out of seeing your tech dump water over your head or give you a mid-song drink.

Photo: Ross Halfin

Mike: [laughs] Well, the guys don’t really like to stop between songs. They like to keep the momentum going and let our music speak for itself. It was different with Ozzy because he would spend time talking to the audience. But that’s not how we do it here, so I need to keep cool on the fly. Between songs, it might only be enough time to go “1-2-3-4,” and boom—you’re right back in it.

MD: It reminds me of a boxer or a marathon runner refueling without stopping—and really, it’s an athletic endeavor, drumming as hard as you do.

Mike: I feel so. And to me, that’s what live music should be; it should be physical, it should be in your face, it should be compelling and energetic and powerful. Otherwise, you might as well sit at home and watch it on your computer. I want some hair on it where it needs to be. And certainly all of our guys have that same approach. That’s just sort of where we come from. It’s that punk rock ethic. Musically I feel like I’m as much Black Flag as I am Black Sabbath, you know?

MD: Watching you play, it’s clear that you still just live and breathe drumming, like you were born to do only this. How old were you when you started?

Mike: I was thirteen years old. It was 1975 and I was sitting in my friend Cliff Burton’s bedroom and he said, “Hey man, I’m going to play bass.” And I said, “Okay, I’ll play drums.” It was a total knee-jerk reaction. It was completely unthought-out. And from the moment I started playing it kind of took over for me. It was an obsession, but it was positive. It was something that kept me out of trouble and defined those middle years where I could’ve gone way off the rails and gone the wrong direction. When I first met Ozzy I told him, “You don’t know me, but Black Sabbath saved my life.” And that’s the power of music. That’s the beauty of it. It’s transformative. Advertisement

MD: Wow. Cliff Burton.

Mike: Yeah, we’d already been friends for three years or so—at that time that’s like a third of your conscious life! And we just loved music, all kinds of music. A major turning point was when the two of us saw the Sex Pistols at Winterland. Would you have guessed that judging by where Cliff ended up professionally? Maybe you would, but the point is, we were open-minded. We were open to evolution. Evolution is important. You’ve got two choices: you’ve got to roll with it or it’s going to roll right over you.

MD: Were you self-taught?

Mike: Well, yes and no. I learned the basics from a guy who was one of the satellite teachers for this dude Chuck Brown, a pretty renowned drum guru and old-school badass here in the Bay Area. We worked out of Charles Dowd’s Funky Primer and Benjamin Podemski’s Standard Snare Drum Method, stuff like that. Then a few years later I studied with this dude from Ghana in a class at Berkeley that was a group percussion ensemble that had nothing to do with the drumkit. He would dance and sing and talk in different rhythms, and clap his hands in different formations and patterns. At the same time I was listening to guys like Paul Ferguson from Killing Joke and Pete de Freitas, who played in Echo and the Bunnymen—guys who played these amazing tom patterns. So I would say that I walked up to the banquet table and tried all the different things in the smorgasbord and sort of took what worked for me, you know?

MD: How did the songs for Sol Invictus come together? I know “Matador” was being performed live for some time on the reunion tour.

Mike: “Matador” was very important because that was the first new song. Bill brought in a demo with some ideas and we all worked it out—face-to-face, all of us together—and then took it on stage. We didn’t advertise it, we just played the song. At that point I think we all felt that maybe we did have something more to say. From there, people brought in more demos and songs emerged from jams. But “Matador” was the first one, and I think it turned out beautifully on the record. Advertisement

MD: There are shades of Angel Dust on “Matador” and also “Separation Anxiety,” with that dark atmosphere and powerful, hypnotic grooving. The tension builds so patiently and perfectly in those songs, and there so much space throughout the record. That’s something that always set you apart from so many other hard rock bands.

Mike: Well, thank you. My favorite part on “Separation Anxiety” is in the chorus, or the “B” part, I guess, when the downbeat sort of flips. The guitar changes at that point and kind of plays against the rhythm, which is really fun. I love the bass line on that song, too. It’s just smoking— especially in the outro. We’ve always been cognizant of leaving plenty of room for each other’s parts. I just try to lay down something good and solid and I trust that the other guys will have something good to say on top of it. I’m not trying to fill in every single nook and cranny, you know?

MD: Do most songs come from you and Billy working out a groove, or is it different for every song?

Mike: It’s different for every song, but at the end of the day, the bass and drums are pretty prominent in this band. It’s sort of counter to the norm, but it’s just…Bill and I were never put on a leash, you know? There were never any rules. We were always given leeway to take up a lot of sonic real estate. Songs like “We Care a Lot” and “Epic,” for instance, both of those just popped while Bill and I were jamming. But no, Mike writes songs, Roddy has written a few on this album. Jon [Hudson, guitar] is always bringing in cool stuff. Advertisement

MD: Are there any other new songs that you’re particularly fond of from a drumming perspective?

Mike: I could say something good about every song, to be honest with you. Overall, I love the drum tracks because I think they sound very fluid and natural, and I still recognize them after they’ve come out of the other end of the mixing and mastering meat grinder. They still sound like the drums I played. They don’t sound too dressed up, or changed, you know? They feel honest to me, which is great.

Specifically, I really like “Black Friday” because I think it’s quite different—it’s something we haven’t done before. It’s got a good, brisk tempo with lots of acoustic guitar. I love “Superhero” because I like the power and the drive. A lot of times when you do something loud and aggressive in the studio, it can come off sanitized or flat, but I think that song is the opposite of that. To me it sounds like it’s going to jump through the speakers and grab you by the throat. “Cone of Shame” is just awesome. I love the way builds and explodes. And it doesn’t really repeat. It’s not a typical verse/chorus arrangement. It builds and builds and then it just blows up.

MD: What was drum tracking for Sol Invictus like? Did you do it all in one shot?

Mike: Just the opposite—it was a progressive process. We were set up in our rehearsal studio, which was fabulous because it was just us, mainly just Bill and myself. It was very comfortable to have my rhythm section partner also be the producer. And if Bill added a section or Mike altered a melody, I had the opportunity to rerecord a part that was sympathetic to those changes. So it was really an evolutionary process in the best sense. It wasn’t like back when the studio cost us three grand a day, and we’re borrowing the money from the record label and everyone’s like, “We’re going to need you to do all of your drum tracks in three days—hurry!” [laughs] Advertisement

We did whatever the hell we needed or wanted to do to make the best record possible. Corners weren’t cut because of the label, because of MTV, because of getting a song on the radio, because of any other crap that doesn’t necessarily have to do with the music you’re making. That stuff has more to do with selling your music or marketing it, you know? Because we didn’t have that, it felt exciting, it felt energizing, it felt positive—all of those good things.

MD: Did you have negative experience in the past with producers? You were able to put out some pretty weird music on major labels.

Mike: [laughs] Yeah, exactly. Well, the answer is no, because Matt Wallace, a family member of ours, did the records with us and he was always on board with what we were doing. But the answer also is yes, because after the records were done the label would say something like, “The Real Thing is a really great pop record. This is what you are, so you have to do that again.” And we were like, “F**k you, we already did that.” The Real Thing, Angel Dust, King for a Day, Album of the Year—they’re all really different, you know? And every time we finished one, we encountered resistance based on what we’d done the last time. It would take a while for people to digest what we’d done, and then the next record confused them because they couldn’t put it in the same box. But that’s the nature of evolution. It’s what we do, you know? We’re not going to repeat ourselves. We’re not going to imitate ourselves, because we think it’s boring and dishonest.

MD: Your parts are structured pretty specifically. How much room do you leave for improvisation?

Mike: Well, the parts are the parts. I want my grooves and my patterns to be compelling enough to where I don’t feel like I have to justify my existence in the space of four counts between the verse and the chorus. So I always try to make my time really count and not just sort of say, “Well, now there’s singing so I’m not really going to do anything.” I always want my time to be interesting and make that the meat of the meal, you know? So there’s a definite road map, and I’m going from point A to point B, but certainly there are different points along the way that I may take a corner at a different speed or be in a different lane on the freeway, so to speak. Advertisement

MD: You’ve always been a Yamaha guy. Which line of drums do you use these days?

Mike: The album was recorded on my practice kit, which are Absolute Maples—14″, 15″, and 16″ toms with an 18×24 power-sized kick. Live, I’m using a Custom Oak kit—same sizes. Those oak drums are just phenomenal. They’re so weighty, and I get so much tone and projection out of them, especially the kick drum.

MD: You also have a signature Yamaha snare.

Mike: Yeah, that’s such an awesome drum. The shell is a 2-mm chunk of copper, which I believe is almost twice as thick as their other copper snares. It’s 6.5×14 and the bottom half is hand-hammered by an old Japanese dude with a ball-peen hammer. That gives it a warmer tone than your typical metal snare. I just love it. It’s versatile as hell.

MD: Did you use it on Sol Invictus?

Mike: Absolutely, the whole way. At times I tried to put up a different drum to see if it sounded any better and it never did, so I just kept going with it.

MD: Speaking of signature gear, your giant rack toms and the way you position them perfectly flat is iconic. How did you arrive at this setup?

Mike: Well, with the big sizes I think it goes back to being younger and playing shows without a P.A., or playing shows on an un-miked kit set up on the floor, you know? You want something that’s going to cut through, something that’s going to give you weight. And with big drums, especially in loud, aggressive music, you’re going to get more weight behind you. And I like how you catch a little rim on your tom when they’re flat like that. It gives you a bit of additional percussion. I used to use a 14×26 kick, and that even got the toms up higher. And they used to be 15″, 16″, and 18″ toms! [laughs] I’d rather hit the drum less but have it stay hit once I hit it, you know? It’s a quality over quantity thing, and that goes back to the parts. Faith No More is pretty rhythmic, you know? And Bill and I always wanted to make our parts interesting and meaty—we weren’t concerned with crazy, gaudy fills and embellishing the music in that regard. Advertisement

I’m also a left-handed person playing a right-handed kit. If you’re a right-handed drummer, your go-to drum is your floor tom, and you can ride on that with your right hand, you know? So it always made sense for me to start with a big drum because that number-one rack tom in some ways corresponds to a right-handed person’s floor tom. I’m starting bigger, rather than winding around backwards. Ultimately, it was kind of an experiment. I just figured out how to make these tools work for me in my own way rather than worry about what everyone else said I was supposed to do with them.

MD: Just by virtue of you being a lefty playing open on a righty kit, it makes your parts idiosyncratic. Even though they’re not overly splashy, a righty playing a righty kit can’t duplicate them verbatim.

Mike: I know, a lot of people say that and it drives them nuts. [laughs] But it’s not on purpose. I’m not trying to be tricky or confuse other drummers. It’s just how I turned out, you know?

MD: Does playing open-handed enable you to hit harder and get those crushing downbeats?

Mike: Absolutely. That was the whole point, to not be limited by the underside of your top arm. I was always looking for power. I was looking for that satisfaction of smacking the shit out of something and having a sound good. There’s a certain way that you’ve got to hit a drum to make it sound the way it should. You can’t go too soft. You certainly can hit it too hard, I get that. But you can’t hit too soft. So no question, keeping my hands open has influenced that. Advertisement

MD: How often do you change heads? And how many sticks do you go though on a given show?

Mike: The snare head gets changed every day; the toms are every second show. Back in the day, it was several snare changes a show. I mean, like four or five a night. Especially with Ozzy and his long sets. Now there are no snare changes unless, knock on wood, something happens. And the same with sticks—I used to do eight or ten pair a night. Now I’ll break two or three pair at most.

MD: You’re one of the all-time great flammers.

Mike: [laughs] Thank you.

MD: Along with your tribal tom grooves, that’s always stuck out to me when listening to your playing. What’s the secret to achieving a Mike Bordin-sized flam?

Mike: You know, it’s nothing I ever worked on or thought about really. My flams are always a little bit open. Certainly you can hear it’s not the same note—it’s not one on top of the other. And how I play them is just…that’s kind of my fingerprint. That’s just how I feel it. It’s certainly driven recording engineers nuts back in the day with the editing block and the 2″ tape. They’d be like, “Well, shit, there’s not one snare hit, there’s two! That doesn’t compute. What am I gonna do”? [laughs] A flam is like a fist smacking you in the face. It’s like typing in all caps or something. It’s just always been a way for me to punctuate or accentuate a snare beat.

MD: You’re being emphatic and economic at the same time.

Mike: Totally! I’m not playing faster or playing more notes or anything. But I’m certainly going “Baahhh!” [laughs] It’s just more emphasis. And I’ve got a bass player who likes to hit his bass. He hits it, and you can hear that. So flams work well with the physical nature with which Bill plays. Hopefully I use them where it’s appropriate. Because it’s a seasoning, you know? You’re throwing in a dash of cayenne pepper where you need it, rather than spilling it everywhere. Advertisement

MD: You’ve played with a number of monster bass players in your time. But you and Billy obviously have a special connection. Is it just sort of an unspoken understanding at this point?

Mike: It always kind of has been. You know, starting with Cliff—what a gift. Playing with Robert [Trujillo] and the great Geezer Butler, who’s the king of everybody—again, what a gift. But with Bill there’s just this weird language that we use to relate with one another. And I don’t think that particular language is very common, it’s unique to who we are as a rhythm section. And when it works well, in a collaborative sense, it’s really great because the result is more than just two people. It’s like the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. And like I said, to get a second chance to play with Bill and all the guys—it’s just so special. I really treasure it.