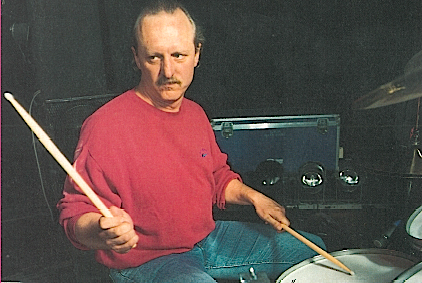

Butch Trucks: 1947–2017

In a week that was already rocked by the deaths of Can’s Jaki Liebezeit and Spooky Tooth’s Mike Kellie, the drum world was shaken for a third time by news this morning of the passing of founding Allman Brothers Band sticksman Butch Trucks.

The Allman Brothers Band, initially led by keyboard player/vocalist Gregg Allman and his older brother, the late guitarist Duane Allman, was one of the most important groups in the history of rock ’n’ roll, successfully infusing American roots music like country and R&B with long improvisations inspired by modern jazz, which were fueled by a dual-lead-guitar/dual-drummer lineup. Among their highly regarded recordings are the 1971 double album At Fillmore East, which contained live renditions of two of classic-rock’s most famous jam vehicles, “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” and “Whipping Post”; 1972’s Eat a Peach, which featured the FM staples “Melissa,” “One Way Out,” “Trouble No More,” and “Blue Sky”; and its follow-up, ’73’s Brothers and Sisters, which boasted the hits “Ramblin’ Man” and “Jessica.”

Trucks and his longtime kit partner, Jai Johanny Johanson, aka Jaimoe, were first featured in Modern Drummer magazine in their May 1981 cover story. The pair were interviewed once again in March 1991, on the heels of the Allmans’ 1989 reunion tour and the release of its first studio album in nine years, Seven Turns. Despite some turmoil within the group, including the loss of founding guitarist Dickey Betts, the group remained a hugely popular working unit until formally calling it quits in 2014. Here we present some choice Butch Trucks quotes from the 1991 story. Advertisement

The group’s 1989 reunion tour

The purpose was to see if we could still do things with the music that we used to do. Epic, our new record company, wanted us to go right into the studio. They were convinced that within two weeks on the road we’d split up. But we had three new guys in the band, and we had to see how that would turn out. Plus we wanted to see if the music was still viable and whether there was still some communication going on. As soon as we realized that the music was happening, the goal was to go into the studio and make a new record.

We told Epic that if we were going to make a record, we were going to do it on our terms. We told them we didn’t want any input from them about the music, the producer, the studio—whatever. We wanted complete freedom to do things the way we wanted to do them, or else we weren’t interested. They said fine.

We wanted to go back to our original philosophy and play the kind of music we wanted to play—with no thought to commercial success. The one thing I wanted to avoid at all costs was any further compromise. That was my biggest anxiety. I wanted to be quite sure we were serious about this, that everybody was committed to the band and willing to bare their guts once more. In the early ’80s it had gotten to the point where we were playing it safe and not taking any chances. We were just making the money and going home. Advertisement

It took Jaimoe and I about forty-five seconds to get our groove back. We started playing ’In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,’ and once we hit the jam, tears just started rolling down my cheeks. I said to myself, ’So this is what’s been missing from my life.’

After the 1982 breakup

I tried to be a businessman in Florida. I raised about $3.5 million in investments and financing and built a recording studio called Pegasus. It was a great studio, but it didn’t last. I wasn’t the businessman I thought I was. [laughs]

I also taught some classes at a local community college. The course that was the most fun to teach was called The Business of Music. When I heard that the Allman Brothers Band had gotten screwed down the line, I wanted to find out what was going on. I figured if I offered a course about the music business, I’d learn about it—and I did. It was the best thing I ever did. The other classes I taught were music history courses, and I gave something of a contemporary viewpoint to the stuff being taught. Advertisement

On the lack of bands that adopt a two-drummer rhythm section

There aren’t a whole lot of drummers that can play together. This type of music generates a lot of very big egos. You have to have people who are musicians instead of personalities. They have to be interested in playing music rather than padding their own nest. When two drummers sit down to play together, it usually turns into a competitive thing: “I’m better than you are, so I’m going to play more.”

Origins of the Allmans’ double-drummer lineup

Back when Duane came to Jacksonville, Florida, to put together a band, he came with Jaimoe. Originally it was going to be a trio: Duane on guitar, Berry Oakley on bass, and Jaimoe on drums. They were going to call it the Duane Allman Band. They came to Jacksonville, and we just started jamming. It didn’t take us long to realize that we had something going on that was real special. One day we were over at the big old house that Berry and Dickey Betts had. We started jamming—Berry, Dickey, Duane, me, Jaimoe, and Reece Wyans, who was with Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble. We started this shuffle that went to a slow blues, then to a 3/4, and then to a funky thing. This jam lasted a couple of hours; we just kept playing. I mean the stuff was flyin’! You’d get chill bumps up and down your back one minute, you’d be crying the next—at least I was. I was feeling things that I never before felt behind the drums.

When we finally finished I looked over at Jaimoe and said, “Man, did you get off on that?” He had this grin that went from ear to ear and said, “Yeah.” Duane went to the door and said, “Anybody in this room who’s not going to play in my band is gonna have to fight his way out of here.” It was something that just happened. Advertisement

Me and Jaimoe, right from the beginning, began doing things on the drums that we had never done before. We were pushing everybody who was playing with us to much greater heights. And that’s just the way it’s been ever since.

The 1990 comeback album, Seven Turns

We decided to go back to doing things the way we’d done them originally. We spent a month in Nashville rehearsing. During rehearsals new songs would be introduced. Whoever was responsible for the song would come into the studio and play it for the rest of the band. We’d listen and then react to it, playing things that we thought should make up the song.

Basically our approach has always been to search out the right feel, the one that’s going to make the song go. We’ve never been big on overdubs or any of that studio stuff. We’d set up, play, and record. We’d do it all live. There was very little overdubbing. Even the solos were played live with the track. But that’s where the communication comes from. You can’t communicate with a tape. Playing music is like a conversation. You’ve got to have both sides talking, or else nothing is said. And it worked. I think this record is the best studio record we’ve ever made. Advertisement

Keeping dual drumming from becoming too busy

We just listen. We don’t talk about it. When we’re first working up a song, we might say something like, “Well, in this part of the song I’ll play the 2 and 4 and you play the 3.” Other than that, it’s a matter of being a musician rather than just a drummer. You listen to the song and to all the parts and how they fit, and you make sure you communicate—not only with your partner, but also with the bass player. I try, for instance, to always have my bass drum follow the bass as much as possible. But Jaimoe and I, we don’t work out parts. Essentially we play what we want to play. Hopefully what we want to play is what’s going to work.

I don’t ever notice myself getting in Jaimoe’s way, or vice versa. It’s like a sixth sense we’ve both developed over the years. I intuitively have a feel for what Jaimoe’s going to be playing. I mean, I’ll think to myself, I’ll play a fill here because I know he won’t, and he’ll think the same thing. But maybe think isn’t the right word. You can’t think about something like this. It has to be intuitive. I’m sure of that. The music is going too fast. It’s like having an in-depth conversation with somebody. It just flows. You start thinking about what you’re saying, and all of a sudden you’ve got gaps in the dialogue.

Drum solos

Jaimoe and I have been doing drum solos since we started. Not playing solos would be like making love and not kissing. Solos are fun to play, and they seem to be one of the highlights of the evening for the fans, if you consider the reaction we get when we play them. There are things Jaimoe and I do during the solos that really get the crowd going. Advertisement

It has to do with the way we set the whole thing up. I’ll play a solo, and it’ll be okay. Then Jaimoe will play a solo, and it’ll be okay. But then we start soloing together. We trade fours and build up and get things really rolling—and then cut it off, just like that. We’ll reach that climax point, and then zap! We’ll just cut it off. And the crowd goes nuts.

For years and years I’d get into a feel or basic pattern and then be scared to change it. But I’m starting to get to the point that I’m able to turn it loose, to play a little freer with the rhythms and toy with new concepts. Jaimoe’s always been able to turn it loose. Boy, he goes this way and that way, and it always seems to work.

The influence of jazz on the Allman Brothers Band

When we first started playing together we’d have these long jams. The jams, in the beginning, were built from songs like “Hey Joe.” But within two weeks, Jaimoe turned us on to Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and that’s about all we listened to for a long time. We didn’t listen to any rock ’n’ roll at all. That had a big impact on us; we started getting a little more complex. We started experimenting with rhythms and melodies. Advertisement

As a kid I listened to too much Joe Morello [of the popular jazz group the Dave Brubeck Quartet]. I had to get over that. Then there was Elvin Jones [John Coltrane] and Billy Cobham. Billy’s awe-inspiring. We did some tours with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and God, it was hard to get on stage after they were through playing. It used to piss me off because the crowd would boo them. Good gracious, they were good.

On critics who accused the Allmans of being stuck in the past

That’s their problem, not ours. That’s asinine. Look at Beethoven. He came up with a new way of expressing himself in music. But it was pretty much the same after that. He did it for forty or fifty years. He did it better and better, but it was still Beethoven.

The Allman Brothers Band came up with a form of music that is uniquely our own. Nobody else plays music quite like we do. It would be ridiculous to say that we’ve got to reinvent the wheel every five years. The music that we play is the best music that we can pull out of ourselves. If we try to do or play anything else, it just doesn’t work. Advertisement

Original interview by Robert Santelli. Photo by Barry Goldenberg.