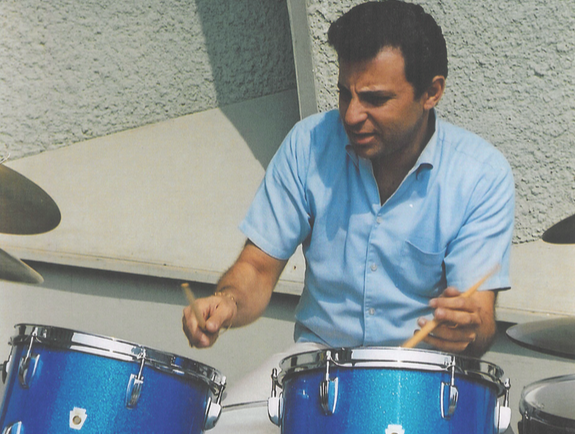

Web Exclusive: Hal Blaine

by Dennis Diken

The July 2017 Modern Drummer is a special theme issue about the birth of classic-rock drumming. In it we examine the work of some of the most famous and influential players of the time, including the Beatles’ Ringo Starr, the Doors’ John Densmore, and Vanilla Fudge’s Carmine Appice. But the drummer who likely played on more hit records in 1967 than anyone else was studio king Hal Blaine, who also found the time to record his own, appropriately wild-and-crazy solo album that year. Here Smithereens drummer and rock historian Dennis Diken continues the discussion he had with Blaine that appears in the issue.

MD: Hal, you explained earlier that you always tried to get the motivation behind a song before recording.

Hal: I actually learned that when I used to work as an actor. All the great actors, like Sal Mineo and Yul Brenner, would talk to me about their motivation all the time. But when it came to recording, it all depended on the song. When I’d hear a song, that was my motivation.

But I started thinking that way long before I ever started in film. When I was working nightclubs, these gals’ music had drum parts that were three to five pages of music. And we were just a piano, trumpet, and drums trio, that was the band in these strip joints. That’s all they would pay for. Advertisement

They did their dance to do the three songs—slow, medium, and fast—and they were off. But I used to try to do cymbal swirls and play with dynamics. If the girl was doing a certain movement and I was playing my floor tom, they’d love that! I wasn’t just sitting there playing buzz rolls on 1 and 2 like they did with so many strippers.

And those gals would come to me, very nice gals. Because in those days it was not pornographic. They were dancers, most of them. Many of them were married with children at home. Anyway, I’m with this stupid little three-piece band and they would say, “I [work] with the big orchestras but there’s something about the way you play for me. I really appreciate what you’re doing. You’re making my music sound like music.”

But for me, going to school all day and playing all night, sight reading, it was great basic training, obviously, for a drummer.

MD: Looking for motivation was probably the key to your success. Because you really cared; it wasn’t just about showing up, getting the job done, and grabbing a paycheck. You put your heart and soul into it. Advertisement

Hal: Also, it depended on the time of day, which studio we were in, who the producer was, what mood you were in…. Maybe you just came from a divorce hearing. Like a good policeman or a good referee, I tried to come in with a clean slate.

MD: A typical downbeat was 8 a.m.?

Hal: Well, I usually walked in by a quarter-of to grab a coffee and make sure I was in the right place. My tech, Ricky Foucher, already had my drums set up for whatever session it was. If the music was already passed out, I’d take a look at the chart. If the producer was there, and they usually were, I’d talk with them or ask the engineer to play the demo or whatever we were going from. Maybe the songwriters were there, and maybe they had ideas. We would talk about it and that was it. We’d go in and kick it off.

Almost all of the stuff was union at the time, three-hour sessions. But they could hold you for an extra thirty minutes if necessary. If it was a commercial, it was a one-hour call, but they could hold you for, I think, fifteen minutes over. But it all depended on what your schedule was. Advertisement

If you weren’t working after the date you [could stay] if they wanted to continue on for overdubs or anything else. You could do an extra hour, and a three-hour session would become a four-hour session. A jingle might become an hour and a half. It all depended on what was going on in the minds of the people that were making the record. Because it was like a committee, especially when you did commercials. We would go in, knock out a commercial within fifteen, twenty minutes.

There were five or six advertising agency guys sitting there and they all had something to say. The first would say, “I think it’s too slow,” the second guy would say, “It’s too fast,” the third guy would say, “It’s too busy,” and the fourth guy would say, “It’s not busy enough.” Everybody had an opinion. They weren’t really musicians, they were guys who were working and trying to do the best they could, and if they had nothing to say they could lose their jobs. So they had to say something to justify their existence.

MD: You were always the guy who broke the tension at sessions and kept a positive outlook.

Hal: I remember going out once and having a talk with the guys, around the time I started contracting—which meant I was calling musicians for work. I’d be at a date and the guys would start arriving. One time this one guy in particular, who will remain nameless, walked over, looked at the music, and said, “The same old shit, every day.” Now, all the microphones were on, and the producers or the ad agency guys or whoever were in the booth. It didn’t usually happen with jingles, but it happened with records, and I told his guy, “Listen, man, you don’t realize it, but all the microphones are on, and that producer heard you say what you said. Now he’s going to come to me and say, ‘I never want to see that guy on another date of yours.’” And that would be it. I’d say, “Do you like your new house? Do you like your new car? Do you like your new set of golf clubs? Do you like the fact that your kids are going to a great college?” So I started that whole thing: “If you smile you stay around a while. If you pout—you out!” Advertisement

MD: That’s true of everything in life.

Hal: Exactly. Attitude means a lot. You know, I used to tell the guys, when you take a five-minute break, especially on records…I mean, unless you’ve got to go to the bathroom real bad or something, or there’s an emergency, act like you enjoyed what you just did. Come in and say, “My God I love this song!” or, “I think we could do a better one.” Or if you made a mistake, tell somebody. Don’t let them find out when they start to mix two hours later or two or three days later. Show some interest in what you’re doing.

They never did that with Frank Sinatra or Andy Williams or Johnny Mathis or those kinds of people. It just wasn’t said or done that way. Everybody was kissing ass, for one thing, depending on who the contractor was. Because the contractors were like the Adolf Hitlers of the union. It took them a long time to become contractors, and they were absolutely Nazis. They’d sit out there and watch and listen, and if you made a mistake they put a little check next to your name. And you’d never get another call from these people. They expected absolute perfection, and that’s all there was to it.

If you were late two minutes coming in, I don’t care if it was raining out…unless you had a motor accident or something and you were in a cast, there was just no excuse for being late.

That’s why R and R—rock ’n’ roll —came to stand for Responsibility and Reliability. The guys started smiling. And we were so lucky because every songwriter wanted us to record their songs. And these producers came from every city in Europe and South America and Mexico, everywhere! Advertisement

MD: Well ,that attitude you’re talking about comes through in the music.

Hal: They trusted us. Arrangers used to tell us, “Listen, guys, don’t even look at your part, just do your thing.” They wanted a hit record, and they knew that everything we were doing was becoming hits. It was a brand-new genre, this rock ’n’ roll thing.

MD: Can you recall how things changed in the business since the time you started out?

Hal: You know that there used to be two unions? There was a black union and a white union.

MD: I didn’t know that.

Hal: A lot of people don’t know that. Eventually it all came together.

MD: When did they merge?

Hal: It was probably in the early to mid ’50s.

MD: You often talk about Rick Foucher, your tech, and how he came up with innovative ideas.

Hal: If I wasn’t using one of my sets, it would be in Ricky’s backyard being completely torn apart. He took off every piece of hardware, like the tuners on the tom-toms, and wrapped them with moleskin.

I remember being at RCA one time. The studios there were gigantic. When you hit a drum, they all sang together with sympathetic vibrations. I was personally not very happy with that. And Ricky made them became absolute perfect for recording. Engineers went nuts, they loved it! Advertisement

And the cymbals created leakage. Phil Spector was the only guy who loved that, but one of Ricky’s tricks was that he would take my cymbals and bury them in the sand for a week or ten days if I was on vacation. And I didn’t know this! He did that on his own. In his backyard there was something in the chemistry or the chemicals of the sand and the dirt, and it killed that terrible curse of the overtones.

MD: That’s fascinating.

Hal: I know! And I bought those cymbals in the ’40s. As a matter of fact, the new Zildjians has a new line called Avedis, they’re all being sandblasted.

MD: I have a set of those too, I just love them.

Hal: I have my new DWs, which I just love. Still with Zildjian, still with Remo. It’s very fulfilling.

MD: With the current issue of Modern Drummer focusing on 1967, do you have any specific recollections about that year?

Hal: Yes. Mike Nesmith of the Monkees was a sweetheart. Of course a lot of people don’t know about his background. He was a multi-millionaire and he was born with a silver spoon. His mother invented White Out. He came to me one day and he said, “My attorney says that I’ve got to get rid of about $50,000. And I want to do a session—I want you to be crazy and get fifty trumpets, fifty saxophones…” and on and on and on. I said, “Mike, I’ll do whatever you want to do,” and we did this great session for a week or so at the biggest studio at RCA and made an album called The Wichita Train Whistle Sings. And when we played the last note of music, Tommy Tedesco took his white Fender guitar and threw it up as high as it would go. It almost hit the ceiling, and as it came down everybody was standing there, holding their ears, as this beautiful guitar hit the floor and smashed into a thousand pieces. Eventually it went into a frame and was hanging in Tommy’s house for many years. Those were some of the crazy things that happened.