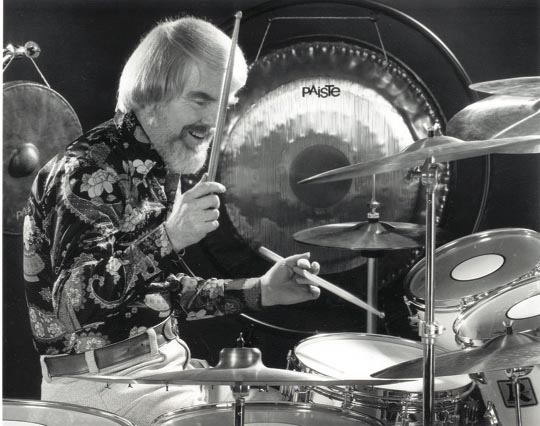

Roy Burns — A Career in Percussion

by Lauren Vogel Weiss

Photos courtesy of Roy Burns

The drum world was rocked by the news of Roy Burns’ passing last Wednesday, May 2. Roy’s connection with Modern Drummer went back decades, to the very beginning stages of the magazine’s history. For twelve years, Burns wrote his popular and long-running Concepts column. He was also an advisor, a confident, and a friend. We will miss everything about him. Here we reprise the last interview he did with Modern Drummer, in 2012.

Roy Burns has been involved in all aspects of the music business for over six decades. From his early days as a big band drummer through his years as a clinician, teacher, and author to his second career as a manufacturer, Burns has done just about everything related to a drum. And that doesn’t even include his penchant for storytelling and his vast repertoire of humorous stories.

From Kansas to New York to Brussels

Roy Burns was born in 1935 and raised in Emporia, Kansas. As a young boy he was enamored of the college band and military recruits doing marching maneuvers. One of the drummers convinced Burns’ mother to get lessons for Roy. “Whoever that unknown soldier was,” Burns reflects, “he’s the reason my parents allowed me to take drum lessons, and that was the beginning of everything.” Advertisement

Burns studied with his high school teacher, and by the age of fourteen he was playing in a local dance band with some former soldiers. “When the drummer left town to go back to college on the GI bill,” he recalls, “I bought his Slingerland drumset.” Burns began to travel by train to Kansas City to study with Jack Miller, his first professional drum teacher.

Roy Burns playing with Teddy Wilson (piano), Arvell Shaw (bass), Benny Goodman (clarinet), and Red Norvo (vibes) on Texaco’s Swing Into Spring, a 1958 TV show celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Goodman’s band

At the age of seventeen, Burns encountered the first of four people he credits as major influences on his career in music. “I met Louie Bellson in a Kansas City studio,” Roy remembers. “He heard me play, and he said, ‘Kid, you’re as good as you’re gonna get if you stay in Kansas. Go to New York or L.A. to study.’ So I took him at his word, and two years later I got on a train with $300 and a drumset and went to New York City.”

Burns arrived in the Big Apple in 1955 and began taking lessons with Jim Chapin and Sonny Igoe. “I met Sonny in Kansas when he went through with Woody Herman’s band,” Burns says. “So when I got to New York, I looked him up and took some lessons. About a year later, he recommended me to Woody Herman. I got the audition and went on the road with Woody Herman’s band, which was my first big professional gig.” Burns credits Igoe as being one of the people who influenced his career, and the two remained lifelong friends until Igoe passed away in March 2012. Advertisement

During a week off from touring, Burns got a call from Benny Goodman. “I auditioned for Benny just playing brushes on some tunes while Mel Powell played piano,” Roy remembers. “And after two hours he said to me, ‘Be at the Waldorf tonight, and wear a dark suit,’ and he walked out. I wondered what the heck was going on! So I went to the Waldorf and sat over in the corner. The band played a dance set, a concert set, and another dance set, and then the manager comes up and says, ‘Benny wants you to play the next concert set.’ So I went down and met [Elmer] ‘Mousie’ Alexander, who was the drummer. He said, ‘Kid, don’t worry about me—I’ve already given my notice, and I’m leaving the band. But this is a hell of a way to audition, in front of a live audience on somebody else’s drums with no rehearsal! I’ll help you all I can.’

“He talked me through the arrangements, and when I finished the forty-five-minute concert, Mel Powell leans in from the piano and says, ‘Congratulations, young man.’ Then Mousie says, ‘Gee, you really listened. You played the show just like I did, on my drums, and with no rehearsal. I hope you get the gig.’ And I did.” Burns played with Goodman for the next three and a half years, traveling all over the world.

Burns circa 1962

“The most famous place we played was the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958,” Burns says. “That concert was recorded, and Westinghouse, which was one of the sponsors of the tour, put out a promotional Benny Goodman album for a dollar, and my solo from ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ was on there. That’s what really established my name. It was a wonderful experience, and playing with Benny was great.” Advertisement

This new high-profile gig brought a bit of a problem, which turned into another opportunity. “When I first joined Goodman’s band,” Burns recalls, “I had a little endurance problem. When we played ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ every night, I only weighed 125 pounds! My arms would get tired, and when we got to the drum solo, I could hardly play it. So I went to Sonny Igoe and asked him what to do. He said, ‘Go see Henry Adler.’ Henry was a famous teacher and had a store, so I went to see him.

“I wasn’t sure if that ‘old guy’ could help me, but he taught me a few drum exercises. I said, ‘Henry, is this it? Because I’ve been playing awhile, and these wrist exercises don’t seem like much.’ He said, ‘Do them for two weeks, and if you don’t see an immediate improvement I’ll give you double your money back.’ And after two weeks, I never had an endurance problem again. “The exercises were simple: snapping your wrist in a very controlled style, turning your wrist back to get a full stroke. But they really worked. I had an idea for a finger-control book. I took it to Henry, and he liked the idea.” Adler published Burns’ first book, Finger Control, in 1960, becoming the third person to have an influential impact on Roy’s career.

In the mid-’50s, Burns became a Slingerland endorser. “Sonny Igoe got me the endorsement while I was still with Woody Herman,” Roy recalls. “Then several drum companies approached me about playing another product when I was going to the World’s Fair in Europe with Benny. But Bud Slingerland had been very nice to me, and I turned down the other offers and stayed loyal because he had been loyal to me. Advertisement

“I remember when the Goodman band was playing the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago,” Burns says with a smile. “I’m getting all the drums set up, and I see this big, tall man, about six-four, with a hat and an overcoat climbing, up over the front of the stage, knocking over the potted palm. He walked up to me and said, ‘Hello, I’m Bud Slingerland.’ He went up to my new calf bass drum head, which had ‘BG’ and ‘RB’ painted on it, took a rubber stamp out of his pocket, and stamped ‘Slingerland’ on the front of my bass drum!”

In the early ’60s, Burns left Goodman’s band and returned to New York City. “I started doing work around town,” he says, “and Sonny Igoe asked me to sub for him on The Merv Griffin Show. Merv had a trio on his afternoon show—bass, guitar, and drums. I was subbing for Sonny when he got the job at CBS playing The Jackie Gleason Show, so I took over The Merv Griffin Show. Once again Sonny Igoe was there to help me.” Burns played with Griffin on four different television shows.

Henry Adler played another influential role in Burns’ life around this time. “The Rogers Drum Company was looking for someone to write a beginning drum book,” Burns explains, “and Henry said, ‘Why don’t you get Roy to write it? He hasn’t written any books that have been associated with any other drum companies besides Rogers. He could write a book for you.’ So Henry published The Roy Burns Elementary Drum Method, which became a bestseller. Much to my surprise, I was an author!” All of Burns’ early books were published by Adler and eventually sold to Belwin, which is now part of Alfred Music. Advertisement

From Drummer to Clinician

With Benny Goodman’s band in 1957

In 1965, Burns was invited to travel to England and give clinics for Rogers Drums. “I asked Merv if I could miss the first six weeks of the show and still come back,” Burns says, shaking his head. “Merv said, ‘Either do our show or do your tour, whichever you decide.’ So I talked to Henry Adler, who had become a mentor to me. I said, ‘Henry, what should I do? My friends tell me I should take the TV show.’ He said, ‘Take the clinics. You play great, kid, but nobody knows you. You need exposure.’ So I took the clinic tour, and it was one of the best decisions I ever made.

“At my first clinic in London, there were 800 people there. I got to the question-and-answer session and some guy asks, ‘What do you think of Ringo Starr?’ I said, ‘I never criticize anyone who makes more money than I do!’ Everybody broke up, and the tour went very well after that.”

Burns began doing clinics for Rogers on a freelance basis but was still playing and touring, this time with Lionel Hampton. “One day in 1968,” Roy recalls, “Rogers called me up and said, ‘Every time we need you, you’re doing record dates or a TV show. And when you have time off, we don’t need you.’ So they offered me a full-time position to be their clinician and in-house artist. And it worked out very well.” Burns and his family first moved to Ohio and then to California so Roy could be near the company’s headquarters. He spent about two weeks each month on the road, giving clinics all over the world, from the Far East to Europe to South America. He even did a clinic in Tasmania. Advertisement

Burns worked for Rogers for twelve years. During this time he greatly curtailed his playing career. “The problem with trying to play at night or do studio work,” he says, “is that I wouldn’t pay attention to my day job and eventually it would fall apart. So I made Rogers my first priority, because I liked doing it and it was giving me a lot of exposure.”

Through his association with Rogers, Burns met the fourth person he credits for influencing his career: Henry Grossman, owner of Grossman Musical Products in Ohio. Grossman had bought the Rogers Drum Company in 1953 and, along with design engineer Joe Thompson, modernized the firm. “I was in Henry’s office one day,” Burns recalls, “when his publishing manager came in and said, ‘Roy, if you wrote more drum books, your name would sell them.’ I replied, ‘I won’t do that. I can’t write a drum book unless I think I have a good idea and feel it would serve a need.’ After he left, Henry—who was a tiny little man but a very strong one—walked up to me and said, ‘Young man, you’re right. Always go for quality, and in the long run you’ll win.’ And I always took that very much to heart.”

For a while, Burns continued to play, but not as much as during his early years. “I was the house drummer for the Monterey Jazz Festival for nine years after we moved to California,” he says. “It was fun playing with all those great artists. People like Ray Brown [bass], Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison [trumpet], Gerry Mulligan [sax], Billy Taylor [piano], Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis [sax], and Dizzy Gillespie [trumpet]. I played with so many of them over a period of time that I can’t recall all of them.” Advertisement

In addition to giving clinics and attending trade conventions—he’s been to every NAMM Show since 1960—Burns had a host of other duties. “I wrote the catalogs for both Rogers and Paiste,” he explains. (Rogers was the U.S. distributor for the Swiss cymbal company at the time.) “I came up with sales programs. I worked with the sales reps for their dealer presentations—basically all the things involved in marketing. Plus traveling with the salesmen and teaching them about the products. And that’s what gave me the basis to start Aquarian.”

From Rogers to Aquarian

During his time at Rogers, Burns met Ron Marquez, a contractor for Rogers who owned a powder-coating company called Aquarian Coatings Corporation. One day Marquez asked Burns to tell him about an idea he had, and, in 1980, Aquarian Accessories was born. “That way, when we answered the phone, no matter which business it was, we’d be saying Aquarian,” Burns explains with a grin. And thirty-two years later, he’s still in the office every morning at 8 o’clock.

How did Burns make the transition from player to manufacturer? “It all started at Rogers,” he says. “When they were having trouble getting things done, I said, ‘Well, I could write a catalog’ or ‘I could write an ad.’ Out of necessity I became more and more involved in working with the reps, and I got a great education about the music business in general. So when we put Aquarian together, I was in charge of the marketing and sales and my partner was in charge of the manufacturing. And it’s been a great partnership.” Advertisement

Their first product was a revolutionary cymbal spring. “It mounts on top of a cymbal stand,” Burns explains, “so when you hit a cymbal hard, the spring allows the cymbal to move so you won’t break it. We still sell a lot of them today.” Aquarian also sold graphite drumsticks, although the popularity of that product waned over the years, as well as stick bags and cymbal bags.

“One day Ron and I were talking,” Burns says, “and I asked if he would like to make drumheads. Ron’s the engineer; he copied the general shape and design of the calf drumheads that I brought in, and we started making drumheads in 1989. Those soon became our most popular product.

“We have all the standard single-ply and double-ply drumheads,” Burns continues. “And we recently came out with some heads called the Power Trio. The Force Ten tom-tom head is two 10-mil plies. Usually the 2-ply heads are two 7-mil, but we were able to successfully mold two 10-mil together with a vacuum process that’s a trade secret. We can get the air bubbles out between the plies so they’re very resonant as well as consistent. At the same time we came out with a snare drum head called the Triple Threat—it’s three plies of 7-mil. No one has ever made a three-ply snare head before. Then the product that probably put us on the map was the Super-Kick bass drum head, which has an internal muffling ring and two 10-mil plies, so you don’t have to put a pillow in the bass drum. The Power Trio series has been very successful for us.” Advertisement

Burns has seen many changes in the industry over the decades. “When large corporations entered the music business, they depersonalized it,” he says with a sigh. “It’s harder to have relationships like we used to have. I tell dealers I’m an old-fashioned guy. I remember when the dealers and the manufacturers were partners, because they had the same end customer—not so much an adversarial relationship but more a cooperative one. And that’s what we still try to maintain at Aquarian.

“Drumsets have gotten so expensive that now they’re hard to sell. So it’s mostly accessories that are keeping the door open for a lot of stores. We happen to be in the accessory business, so we’re fortunate in that regard. There are fewer stores, but there are more companies, so it’s a buyer’s market.

“Old-time dealers like Frank’s Drum Shop in Chicago had a huge mailing list, which was their mail-order business. Today the internet is just electronic mail order, but it affects what local dealers do. Drum shops that don’t have an internet aspect will probably lose out.” Advertisement

Burns still fields calls from customers, both satisfied ones and those having problems. “I want our customers to know that one of the owners of the company is available to talk to any drummer at any time if he has a problem or a question,” he says. “I want them to know that to us, the drummer is the most important person in this whole operation. Our job is to help drummers play music, not to trick them into buying a product. If we keep that attitude, then we’ll do okay. After all, music is what brought us together, and that’s what’s important.”

After almost half a century behind the drumset, Burns made the difficult decision to retire from playing. “I couldn’t ride two horses at once!” he says with a laugh. “Running the company while practicing and trying to keep my skills up was getting more and more difficult. I realized I had to make a choice. If you’re going to play, you have to commit to playing. And if you’re going to run a company, you have to commit to that. I realized that I satisfied almost all my desires in playing, so my last performance was for the Modern Drummer Festival in 1997. That was my swan song.” In this special showcase by the Percussion Originators Ensemble, Burns was joined by Vic Firth, Herb Brochstein, Don Lombardi, and Modern Drummer founder Ron Spagnardi.

From Author to Raconteur

Roy Burns and Ron Marquez

After penning more than a dozen drum books, Burns added yet another category to his résumé: magazine columnist. “I had written a book called Natural Hand Development,” he explains. “It was a correspondence course for Dick Grove’s music school. I had a chapter in each lesson called ‘It All Starts in Your Head,’ which was basically about attitude and problems that everybody deals with. That gave me an idea to write a column, so I called Ron Spagnardi at Modern Drummer. He told me to send him a couple of articles to check out. When he called me back, he told me it would be perfect for their Concepts section. So I started writing the column, and I did it for twelve years.” Advertisement

When asked if he had a favorite installment, Burns pauses before answering. “Not really,” he replies. “I enjoyed all of them. But the most important thing was the reason behind it. One day my son was playing his guitar in the garage and my drums were set up in there, so I went in and played a tune with Steve. We played some blues together, and we both got a kick out of it. At dinnertime, I told my wife, ‘You know, Steve has never played with anyone older than he is. When I started out, I was the youngest guy in the big band, and the older guys would give me hints or helpful ideas that helped my playing.’ So that was the approach that I used in the articles—I became that older musician trying to help the young guy.”

Burns once stated that he wouldn’t write a book unless he had something to say.…and he still does, with three new books out in 2012, through Kendor Publishing. “Some of these books I’ve had on my mind for forty years,” he explains, “and I finally have a chance to put them into print. The first book is Solo Secrets of the Left Hand and Bass Drum. It’s quite an original book with all the patterns you can play between the left hand and right foot. We’ve gotten great reviews on it. The second book is Relaxed Hand Technique, which explains how I developed my technique over a period of years. Even though I wasn’t very big, I could still play louder and longer and faster than the other guys. It was because of the techniques I developed with the aid of Jack Miller back in Kansas City. The third book coming out later this year is Creative Drumset Workbook, which has a lot of solos for snare drum. But a student can re-voice the accents for the drumset, so he becomes part of the creative process. I’m interested to see how that book will do.”

When he’s not working at Aquarian or writing a book, Burns is always ready to tell a story about his colorful past. “I’ll tell you my favorite Benny Goodman story,” he says with a grin. “We were playing in Brussels at the World’s Fair—a sextet number with eight guys doing it. Don’t ask me how we did that! But Zoot Sims, the famous saxophone player, said, ‘Roy, you’re playing the brushes on “Flying Home,” and we can’t hear you down in front. So play with sticks. It will help hold us together.’ But I knew that Benny wanted it with brushes, so I said, ‘I’ll play it with sticks but a little softer, and maybe he won’t notice.’ Well, the trick was to get back to the hotel, change out of your band uniform, get out through the front of the hotel and go to dinner without running into Benny! Sure enough, he runs into me and says, ‘Hey, kid! What are you playing on the sextet number?’ I said, ‘Sticks, but real soft.’ He said, ‘Why are you doing that?’ I said, ‘Well, I thought it might help hold it together, since we’re spread apart.’ I can’t tell him that Zoot told me to do it! Benny said, ‘You don’t have to do that. I like the brushes.’ Advertisement

“A couple of weeks go by and the guys are complaining again, so I said, ‘Okay, I’ll play the sticks real soft, and he won’t notice.’ Well, Benny runs into me in the lobby of the hotel right after the concert, and he says, ‘What are you playing on the sextet number?’ I said, ‘Sticks, but real soft.’ He said, ‘Why are you doing that?’ I said, ‘Don’t you remember the last time we talked? I was playing with brushes and you said play with sticks, just keep it down.’ He said, ‘I did?’ And I said, ‘Well, Benny, you know I wouldn’t do it if you didn’t say so.’ Then he said, ‘Kid, you’re doing a great job. Keep up the good work!’”

Burns erupts in laughter. “I had to get off the hook somehow, you know! But Benny Goodman was the greatest musician I ever played with. He would wail like there were 10,000 people out there, even if it was rehearsal. It was like electricity. He was also very consistent—he didn’t make mistakes, and he expected the same from you. He really was the greatest, and I learned a lot of from him. I’ve never played with anybody like that.”