Queen’s Roger Taylor Interview October 1984

A big part of any successful interview is the preparation that’s done before the actual interview takes place. It’s during this stage that the interviewer gets a fix on the interviewee. But trying to size up Queen’s Roger Taylor proved to be no easy task. As the drummer for one of England’s biggest rock bands of the ’70s—to date, Queen has sold well over 50 million records—it was Taylor’s view of his profession that caused me the most problems. Taylor, I sensed, didn’t like to view himself as a drummer, even though that’s what he’s been since his childhood days. In addition, he sort of hinted that he didn’t know much (or care to know much) about the technical elements of drumming, even though he’s always been a highly respected and wonderfully proficient drummer. But the clincher was that Taylor, at least from what I’d heard from friends in the business, didn’t even like to talk about the drums. Yet he consented to speak with Modern Drummer, of all magazines. A difficult interview? It sure seemed that way.

On the way over to the Manhattan hotel where Taylor and the rest of Queen were lodging, I conjured up a mental picture of Taylor dismissing my questions. If he didn’t want to talk about drums or drumming, what then would he want to talk about? The assumption that most people who listen to rock either love Queen or hate it? Perhaps we’d discuss the problems Queen has had with the rock press over the years. There was always Freddie Mercury, the audacious and often brazen lead singer of the band. Maybe the interview would revolve around the joys of being a rock star? Who knew? Whatever the case, I braced myself for a long afternoon—or a short one, depending on how I looked at it.

As it turned out, Roger Taylor proved to be a most interesting subject. The things I had previously heard or read about him were, for the most part, on target. However, Taylor answered all my questions—even the detailed drum questions—and did so in such a warm, affable manner that it was impossible not to feel comfortable with him. It’s true, Taylor doesn’t like to consider himself a drummer in the traditional sense of the term. And he doesn’t especially like talking about the inner secrets of his instrument and the way he plays it. But he has his reasons, and those, I think, were what made the conversation so interesting. Advertisement

RS: You’re a drummer who not only plays drums, but sings, writes songs and plays a very active role in the direction that Queen takes. Some drummers might think that’s an awful lot of responsibility. Is it?

RT: No, I don’t think so. I think drummers suffer from a misrepresentation of image too often. Traditionally, drummers have been regarded as the stupid ones in rock bands. It’s a bit unfair, and because of it, being a drummer is a thankless task sometimes. There’s responsibility involved in what I do, but it’s nice to broaden one’s horizon. These days it’s funny, because I think of myself much more as a musician than a drummer.

RS: Why the change?

RT: Well, it’s because I’ve been spending a lot of time in control rooms, I suppose. Also, half my job in Queen is drumming; the other half is singing. I started off as a drummer and then all these things like singing and writing sort of followed. Advertisement

RS: How do you balance your singing and writing with drumming?

RT: Strangely enough, singing and drumming never bothered me, although I know of drummers who do have problems with the two. See, back when I was in school, the singing bit was forced on me one day when the lead singer in the band I was playing with suddenly picked up and left. We had to do the gig and I had to sing. That’s basically how I became a vocalist.

RS: It sounds as if it was a very spontaneous thing.

RT: In a way, yes, it was. But before that I used to do some backup singing. I found singing and drumming much easier than I expected. Mind you, that was a long time ago. I never had a time problem, so that was a big plus. But physically speaking, it was very exhausting. I mean just playing drums itself is very demanding.

RS: Do you do anything in particular to keep in shape?

RT: I wish I did. I’m thinking of getting a bit of gym equipment to keep at home because I’m getting older. It’s definitely time to start shaping up.

RS: How did you get involved with writing songs? Did you always write?

RT: No, I didn’t. When we first started Queen and I first met Brian [May, Queen’s guitarist], I wasn’t really good enough on the guitar to write. You can’t really write if you just play drums; you need something else, like the guitar. I enjoyed playing the instrument, and eventually I taught myself to write by watching and listening to other people. It wasn’t easy at first, and in the beginning, the songs were far from great. Advertisement

RS: How accomplished are you on guitar?

RT: Well, I really don’t know how good I am on guitar. I know I have a good sense of rhythm. I wouldn’t say I was accomplished on the instrument, but I’m not bad.

RS: How do you go about composing a song? Is there any personal methodology you use?

RT: These days I find it much easier to write melodically on keyboards because the piano is more geared, I think, for songwriting than any other instrument. The guitar is quite a difficult instrument, actually, when you’re trying to compose melodically. You have to have all your chords together, and then you need to put something on top. With the keyboards, you can write the whole song right there. So what I’ve been doing is using a sequencer or something, and keyboards to write material.

RS: How many instruments do you play?

RT: Guitar, keyboards and drums. That’s it really, although I do a lot of knob twiddling with electronics. I recently got a Simmons sequencer. Sequencers are quite good. I’ve been using a Simmons mixed in with my regular drumkit for quite some time now. The trouble with doing that is that you’ve got to treat them; you’ve got to put them through a lot of boxes to make the drums sound good.

RS: You wrote the single off Queen’s latest LP, The Works, “Radio Ga Ga.” It’s quite an interesting song. Where did the idea to write it come from?

RT: I liked the title, and I wrote the lyrics afterward. It happened in that order, which is a bit strange. The song is a bit mixed up as far as what I wanted to say. It deals with how important radio used to be, historically speaking, before television, and how important it was to me as a kid. It was the first place I heard rock ‘n’ roll. I used to hear a lot of Doris Day, but a few times each day, I’d also hear a Bill Haley record or an Elvis Presley song. Today it seems that video, the visual side of rock ‘n’ roll, has become more important than the music itself—too much so, really. I mean, music is supposed to be an experience for the ears more than the eyes. Advertisement

RS: It’s no secret that songwriters and bands are writing songs with videos in mind, more so than the actual musical ingredients.

RT: That’s right. But it’s wrong. It’s upside down, isn’t it? It’s really a bit silly, not to mention ironic, because nowadays you have to make a big, expensive video to promote your single.

RS: Back to the album for a second. Besides “Radio Ga Ga,” did you play a major role in the creation of any other songs?

RT: Well, all the members of Queen contribute in one way or another in the arrangement of songs.

RS: In 1981 you released a solo album, Fun In Space. From a drummer’s point of view, what was the solo record experience like for you?

RT: That album was a bit of a rush job, actually. I thought I’d run out of nerve if I didn’t move on it quickly. And I did it much too fast. I spent most of last year when we weren’t making The Works, making another solo album. It’s in a much different class than the first one. It’s a much, much better record.

RS: In what ways? Can you be specific?

RT: Well, for one thing, I took a year in making i t . I made sure the songs were stronger and simply better. I threw out a lot of songs in the process. I also did two cover versions of other people’s songs that I’m quite happy with. I did a version of “Racing In The Street” by Bruce Springsteen. I’ve always loved that song. I did it kind of mid-tempo, hopefully the way he would have done it, if he decided to do it mid-tempo. His version, of course, is very slow. The other cover tune is a very old Dylan protest song which I did sort of electronically. The song is “Masters Of War.” Strangely enough, a lot of the lyrics hold up quite well today. This one is done slower than “Racing In The Street,” but it’s very electronic. I use a Linn on it. It works quite nicely. Advertisement

RS: What prompted you to get into solo recording in the first place?

RT: Well, I felt I was getting more creative, and I wanted a bigger outlet for it than Queen gave me. I wanted, I suppose, to be more than just a member of the band.

RS: When you write a song, how do you decide if the song should be a Queen song or one that belongs on a solo album of yours?

RT: It depends on what we’re doing at the time. If I get a song on paper and the others like it, it’ll go to Queen.

RS: Have you ever agonized over, say, giving a song to Queen which you knew would have been perfect for a solo record?

RT: That sort of thing hasn’t really affected me yet because I’ve only done the two solo albums thus far. My output has never been that big with Queen. I’ve never had more than a couple of songs appear on any one album. I try to keep the more personal songs for myself, I suppose. “Radio Ga Ga” would definitely have been on my own album if that was what I was doing at the time.

RS: You said before that you enjoy fooling with knobs and dials. Is this something new for you?

RT: We [Queen] got a studio in Switzerland, and I very much enjoy playing with all the new toys that are coming out. I’m certainly more up to date with all the new gadgets out on the market today than I ever was a few years ago. I’m also a lot more open-minded about them. For instance, when electronic drums first came out, I didn’t really like them very much because I never liked the sound of the bass drum. But I’ve found that the LinnDrum is much better in this department, and I enjoy using it. One of the things I came to find out is that when people say you can’t get a “human” sound out of the Linn, they’re simply overstating the situation. Of course, there’s some truth in it, but most drummers who still hold out against electronic drums are only doing so because they’re fearful of losing their livelihood. It is a threat, because now the drums are really good, I mean you can even program in the slight timing discrepancies that come with non-electronic drums. You can even push the beat or lay it back. It’s all there, and you can do it quite easily. You can make it sound human, and because all this technology exists, you simply can’t ignore it. One can’t be retrogressive in this business. It’s like the musician’s union in England; the union took a ridiculous stand and tried to ban synthesizers. That’s like standing in the way of an express train. You can’t stop it.

RS: Is it conceivable for you to think that one day you’ll be playing nothing but electronic drums?

RT: I think it’s quite possible. I mean the solo album I’ve been working on has a hell of a lot of electronic drums on it. There’s also a track on The Works in which we’ve illustrated that quite well, I think. It’s called “Machines.” Basically, it starts off where everything’s electronic—electronic drums, everything. And what you have is the “human” rock band sort of crashing in. What you wind up with is a battle between the two. Advertisement

RS: When you’re composing songs, how do you set about constructing the drum tracks?

RT: Very often I start out electronically and then overlay the acoustic drums. Of course, every track is different, but usually I’ll begin with a Linn with a Simmons sequencer on it. It doesn’t always work, though. Sometimes it’s a disaster.

RS: Can you give me an example of a failure using this approach?

RT: Well, if you have one of those snappy tempos which is done with a box and then you put real drums on top of it, it could very well wind up sounding dreadful. Actually, it all comes down to miking. Today, it’s not uncommon to overmike drums. I mean, putting 15 mic’s around the kit is absurd. All the best drum sounds I’ve ever got came from using four mic’s or five.

RS: You mentioned before your interest in the activities in the recording studio control room. What brought on this interest? Was it just a matter of staying on top of your profession?

RT: Not necessarily. I just found that I was really getting good results on the board. And obviously, I’ve spent half my life in the last 12 years in control rooms, so I just got to know more about their potential. I couldn’t help but take an interest in what goes on inside the control room. But I think recording studios are in the process of changing. Whether people like it or not, the control rooms will ultimately wind up three or four times bigger than what they are now, and the actual studio part will be three or four times smaller. Advertisement

RS: Then surely you must advocate that young drummers coming up in the business learn as much about the recording process and what goes on in the control room as possible, rather than sitting back and letting someone else in the band soak up all the knowledge.

RT: They’re going to have to. Of course, it depends on how broad you want your knowledge to be. If you want to be a drummer and only play drums, fair enough. But I find that very narrow-minded. I could never just sit back and be the drummer, if you know what I mean. Young drummers really should learn the technical side of their profession. If you don’t, you’re going to miss out. And one owes it to oneself and one’s talent to make the most of things.

RS: Why do you think England has been in the forefront when it comes to using electronics?

RT: I don’t know. It’s certainly true, but I don’t know why. Perhaps the answer can be found in the attitude of some musicians there, or in the way kids are brought up there. Generations coming up are sort of force-fed popular music from the age of zero. But then again, I guess that’s true of America as well. The English see the music business as a form of release because the standard of living in England is low—vastly lower than what it is in the United States. For instance, no one has air conditioning in England. In America you can’t go anywhere in the summer without feeling it. Americans take air conditioning for granted. In England, it’s almost unheard of. Advertisement

RS: Queen began in 1971—some 13 years ago. What were you doing just prior to the formation of the band?

RT: Freddie [Mercury] and I were trying to scrape a living. I was at college, but I wasn’t attending very often. However, I was getting a grant and financing a shop where Freddie and I sold artwork. We sold his work and things friends of his did at the art college. That’s how we kept the band going in the beginning.

RS: Were you an artist as well?

RT: Not really. I studied dentistry and then did a degree in biology. I never did get a degree in dentistry.

RS: Were you in any other bands with Freddie Mercury before Queen?

RT: No. I was in a band with Brian, though, and Freddie would sort of run around with us in those days. He had a couple of bands that he was in, but he’s always had such a forceful personality that he forced himself to develop, because he wasn’t such a good singer back then. He’s a great singer now—immensely confident. I couldn’t believe it. We had a jam session with Rod Stewart and Jeff Beck, and Freddie was about four times louder. He has marvelous projection. Anyway, Brian and I played together, like I said. It was a three-piece band called Smile. When it split up, Freddie, Brian and I decided to form a band in 1970. That’s how Queen started.

RS: At the time, what drummers inspired you? Who were you listening to?

RT: I always liked John Bonham, although in England he wasn’t that fashionable. But to me, he was the best rock drummer who ever lived. I’m sure lots of people tell you that when you interview them. Advertisement

RS: More people say Bonham than any other rock drummer.

RT: Well, it’s true. There’s no one able to touch him in the rock world. He was the innovator of a particular drum style. He had the best drum sound, and he was the fastest player. Simply stated, he was the best. Although he wasn’t the easiest person to get on with, his influence was great. He’d do things with one bass drum that other drummers couldn’t do with three. He was also the most powerful drummer I’d ever seen. Led Zeppelin was actually more popular in America than they were in England, you know. You had to be a drummer to realize how good John Bonham actually was. The average person on the street probably couldn’t really know the difference between John Bonham and the next flash heavy metal merchant, or whatever.

RS: Why is that?

RT: The average person can’t understand the subtleties of drumming or just how difficult some of the things he used to do were.

RS: At that time, how much of an influence did he have on you and your drum style?

RT: A lot. I think there are a bunch of drummers in bands today who are nothing but poor Bonham copies. There are so many, and they have nothing of their own style. It’s just John Bonham’s style, but unfortunately, they can’t come close to his sound.

RS: How do drummers make sure that, when they’re heavily influenced by other drummers, they don’t wind up merely as imitators?

RT: Well, that’s up to the individual, really. You have to develop your own style. If you’re any good, you’ll realize which bits work best for you. And I suppose the thing to do is develop them. Advertisement

RS: What did you do to prevent becoming a John Bonham copy?

RT: Well, I didn’t want to sound like him because I knew there was no point in sounding like someone else even back then in those days. This is true no matter how much you admire what they do. So I just tried to incorporate certain aspects of his style into my own.

RS: Anything in particular?

RT: Well, obviously the bass drum. I mean, he invented the whole school of playing the bass drum in a heavy manner. I learned so much just by listening to the first couple of Led Zeppelin albums.

RS: What are your feelings on Keith Moon?

RT: Well, Keith Moon was great. In the early days, he was absolutely brilliant. He had a totally unique style; he didn’t owe anyone anything. The first time I saw him perform was with the Who in ’64 or ’65. It was just great. The Who was an outrageous band—real energy, real art. I loved them. I mean, to actually destroy your instruments— it was the most unheard of thing in music.

RS: When did you start playing the drums?

RT: [Pause] I can’t remember exactly. Can you believe it? I’ll guess and say nine or ten. I remember banging on my mother’s saucepans with her knitting needles. Then, my father found an ancient snare drum in a storage bin where he worked. It was an old brass and wood thing. I started with that. Then I got a real snare drum, and then a cymbal. You just didn’t get a drumkit in those days. I wouldn’t have known what to do with a whole kit even if I had one. The big moment for me was when my father redid up a cheap set of old Ajax drums. It consisted of one tom-tom, one bass drum, one snare, and one minute Zildjian cymbal. It was about two years or so later that I got a hi-hat. Drums were something I naturally felt kind of good at. I found the guitar a lot more difficult to pick up. With drums, you either have time or you don’t. If you don’t have it, there’s no chance that you’ll ever be any good, really. You can’t teach a person time. I found it very easy to pick up and play things like “Wipe Out.” That was the thing to do at the time. But I’ve never been into the very technical sides of drumming. Advertisement

RS: I assume you never took lessons?

RT: No, I never did. But I actually used to give them, believe it or not! [laughs] I couldn’t even read.

RS: And you still can’t read today?

RT: Very slowly, but not to play. I’ve always found it totally irrelevant. I just always felt that what came from within was what I ought to play. Every time I see Carmine Appice he’s going on about all sorts of amazing things. He might as well be talking about cupcakes. No, I’m not really into the technical aspects of playing drums at all.

RS: Where did you go after getting your first kit?

RT: My friends and I started a band at school. We were terrible—really terrible. We didn’t have any worthwhile equipment. It just sort of built up from school until, finally, the bad bands became good bands. I was always the leader of those bands, for some reason. I must have been a pushy one. We won a few band contests in the mid-’60s, which was kind of a break through for me. Then, eventually, I started singing as well. My career just sort of went on from there.

RS: Why the drums?

RT: Well, I used to walk around my bedroom with a tennis racket pretending it was a guitar. But the drums were noisy and I found out that I was better at them. Plus, I enjoyed them more.

RS: Did the Beatles have a significant impact on you as a kid?

RT: No, not at all. When they first broke, you just couldn’t get around them. Everything was the Beatles. But I was never crazy about their music until the release of Revolver. Then they got me. That album was just brilliant and it really affected me rather strongly. But before that I preferred the Who and the Yardbirds—real seminal British bands. Advertisement

RS: With such early influences as the Who and Yardbirds, do you find it odd that you play in what many people consider a “commercialized art-rock band”?

RT: No, not really. It’s difficult to step back and view the band the way other people view it. What’s the public’s mental image of the band? Do they see a string of album covers? I really don’t know. I know I don’t see Queen as an art-rock band. When I think of art rock, I think of Roxy Music.

RS: Queen has had it tough with the press, especially American press.

RT: Yeah, that’s true.

RS: What do you think brought about the friction between the two? I recall some pretty abrasive articles in such magazines as Rolling Stone a few years back.

RT: I can’t stand that magazine. They’re so arrogant—and so are we! That, I suppose, is the problem. I mean, we are a fairly arrogant band. We have had our moments when we were overtly tasteless. But we were also accused of being a manufactured band, which is so untrue. We were just self-generated really. Nobody ever manufactured us. At one point, we were also accused of being fascists. That was during the time of “We Will Rock You.” Some people said it was a cry of manipulation. -It was no more fascist than Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say.” One time Rolling Stone tried to write a political piece on us. I think the guy was deaf or his battery had run out. But it was very creepy. They have this very superior pseudo-intellectual approach to everything. They don’t approach anything with their senses. They were very nasty, and I wrote them a very nasty letter back, which they did print.

RS: In terms of nonmusical decisions made within Queen—the business decisions, the organizational decisions, things like that—how much of a role do you play?

RT: Queen is very democratic. It all comes down to a vote. If it’s three to one, the three win, unless the one says, “I object to this” or “I won’t do this.” Then we don’t do it. Advertisement

RS: The band has survived quite a long time under that system. That’s unusual.

RT: Queen wouldn’t be Queen if one of us left the band, or if we did things differently. The sense of unity has kept us strong. It’s the same band today that it was when we started. I think that’s good. I think that’s important. There’s an old saying: “The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” That applies to Queen.

RS: When Queen goes into the recording studio to record an album, what’s your role?

RT: I’m totally elastic. The whole thing is down to the song. “What does the song need?” is the main question. Whatever it needs, I’ll do it. If it needs a heavy sound, we’ll put the mic’s in the right places, but we won’t use too many of them. The size of my kit is important, too. Sometimes I just use a snare, bass drum and hi-hat. But other times I’ll use a big kit with a lot of tom-toms. I try to remain flexible.

RS: So you don’t have one particular or favorite set of drums that you usually use in the studio?

RT: No. I have kits I tend to use more than others. I have an amazing Gretsch kit in our studio over in Switzerland. It’s got three toms, a snare and a bass drum. It’s a great sounding kit. Some kits sound great; others don’t. Advertisement

RS: What kit do you use on stage?

RT: It changes all the time, but I use Ludwig because they’ve been sending them to me for quite some time. I have a single bass drum and a selection of toms from small to big. I’ve always tended to use very big drums, which is something I’m getting away from.

RS: Why’s that?

RT: They’re so difficult to mike. They tend to be somewhat unclear and less defined than smaller drums, I think. Stewart Copeland sort of proved the value of small drums. He gets a nice, snappy sound out of those small drums. It’s something I’ve always argued with Ludwig about. They made their drums wide, but they never made them deep. Today, virtually all the drums are as deep as they are wide. The depth of the drums is important. I also usually use a Simmons kit sprinkled around my kit. I use a couple of RotoToms as well. Instead of using them as toms, I use them as timbales because they seem to cut through real nice. As for cymbals, I use Zildjian and a few Paistes. I always change my cymbals around on each tour to sort of suit the mood.

RS: What’s your philosophy when it comes to using cymbals?

RT: It seems to be very fashionable these days to say, “Oh, I didn’t use any cymbals on this record.” I love cymbals. I think they’re great. They provide wonderful dynamics. Quite often I’ll overdub very specific cymbals. Freddie Mercury has a cymbal fetish as well. Cymbals are very important; you have to know which ones to use in which places. Advertisement

RS: On stage, it seems as if you play your drums extremely loud.

RT: I do in the studio as well, unless a song calls for something else, of course. I’m not, however, one of these telegraph pole merchants. I don’t believe you need those massive sticks, because if you’ve got decent wrists, which I think any decent drummer should have, the snap comes from there. That’s what makes it loud. Also, you’ve got to be able to do perfect rimshots. That’s what makes the drums loud, not eight-foot long telegraph poles.

RS: On the song “We Will Rock You,” your beat is loud and hard. What kind of sticks did you use on that song?

RT: Everybody thinks that’s drums, but it’s not. It’s feet. We sat on a piano and used our feet on an old drum podium. It’s rather hard to explain in words what we did, but what you hear isn’t drums. We must have recorded it, I don’t know, 15 times or so. We put all sorts of different repeats on it to make it sound big. There’s a catch though. When we do “Rock You” live, I have to do it with drums, so every thing is slightly delayed. Everything is to suit the song. To have just one way of working would result in the inability to change or adapt. A good drummer must be flexible. It’s imperative.

RS: As in the case of successful studio drummers?

RT: Yeah, but at the same time those people are flexible, but only in terms of the material. What they tend to do is use exactly the same equipment all the time. Their kits have probably got tape on them which hasn’t been removed for years. I’m not knocking them, but in an important way, they’re not flexible. They’re good at one particular thing because that’s what they do all the time. They might be with Kenny Rogers one week and Motorhead the next, but it’s still the same for them. Advertisement

RS: Have you ever done, or considered doing, session work?

RT: I used to do the odd session when the band was starting out just to bring in the extra cash. When I could get it, the session was usually just a percussion thing, you know, standing there and shaking something. But session work in England consists of a select group of musicians. It’s very difficult to get into that inner circle. You have to be as good as Simon Phillips to crack it these days.

RS: Why is it like that? Are there so few gigs to go around?

RT: No. It’s like a little mafia, I suppose. There are a few key people who handle most of the work. Hopefully, that side of the business—the Tin Pan Alley mentality— is dying. The new bands with synthesizers and all, don’t really need session musicians to appear on their albums.

RS: Is there anything you can do to get the bright tones out of your drums when you need them, and the subtle, soft tones when you need them?

RT: Well, I don’t like using thick drumheads. That I can tell you. As far as I’m concerned, you might as well be hitting a barrel of lard. Heads should be bright and responsive, and for that, you need a thin head. Some drummers use thick heads and just batter them. What’s the point? That’s not my approach at all, although I do play hard. I like to hear the sound of the drums. That’s why I use the thin heads. But you’ve got to pay constant attention to tuning them. I have to retune constantly throughout a concert. After every song, I retune my snare drum. It’s absolutely mind-blowing. When it’s just right, it’s just right. Amazingly, a lot of drummers don’t tune their drums—or can’t. Advertisement

RS: How did you learn to tune your drums?

RT: I simply taught myself. I always remember what Keith Moon said years ago, because he was very good at this. The early Who records have great drum sounds on them. He used to say, “Just make the bottom skin a little tighter than the top skin.” That’s how you get that ringing sound. I hate hitting loose skins. Live, it all depends on what hall you’re playing. Like at the Forum in L.A., it’s easy to get a great drum sound. But, on the other hand, it’s hard to get a great drum sound in Madison Square Garden in New York.

RS: How much do you play your drums when you’re not on tour or in the studio?

RT: Well, years ago I used to play them a lot. But ever since we’ve really been successful, I almost never play them. I don’t really practice, but I know I should. However, last year I did a little bit of work with Robert Plant. I had to practice for that because I had to learn the material. But that was the first time I actually sat down and practiced for a long, long time.

RS: Do you find it difficult to get back in the swing of things once you have to go back in the studio or on the road?

RT: Oh yeah. It’s a horrible shock. I usually wind up saying, “Oh my God! I’ve forgotten how to do this!” But then it all comes back. You never lose the ability to play, but you forget arrangements and things like that. Advertisement

RS: What about the quality of your drum playing?

RT: Oh that’s affected too. I always need a few days of rehearsal before we get into playing seriously. It always comes back, though. As for touring, the hardest thing is building up stamina. In the future, I plan to prepare myself physically for touring to make it a bit easier. But there are no exercises a drummer can do to get tuned up to perform except to play. You develop certain muscles when you play the drums, and no exercise seems to work them fully that I know of. This is especially true of the legs. Skiing and tennis are very bad for drum mers; unfortunately, these are two activities I enjoy doing. But they work against the development of one’s drumming muscles for one reason or another.

RS: What are your feelings toward touring?

RT: Sometimes I love it; sometimes I hate it because it’s incredibly tedious. We usually have a good time on the road. That always helps.

RS: For a drummer like yourself who has achieved success, is it difficult for you to carry on that special sort of relationship, or lack of a better term, with your drumkit? In other words, is your drumkit your instrument or your business tool?

RT: I know Carmine Appice is just in love with drums to a much greater degree than I am or ever will be. As a kid, I just used to love my drums. Now, it’s just more and more, a tool, to use your term. That’s probably bad. But I must say, I also find it quite difficult to talk about drums, because what I know about them I probably learned quite a long time ago. I never did get kicks out of talking about, say, the latest foot pedals. I find it incredibly boring. I just know what I like, so I don’t really think about it. Advertisement

RS: But how you perceive your drums is really what I’d like to get from you.

RT: Well, sometimes I hate the sight of the damn things! [laughs] Other days I look at them sort of lovingly. I mean, I’m not Charlie Watts, who’s still in love with his Gretsch kit after all these years. One of my problems is that I change kits too often. This makes me figure that my latest kit is just another kit—that’s all. See, it all goes back to what I said early on. I don’t really see myself as a drummer in the pure sense. My love of drums has been taken over by my love of music. In fact—talk about ironies— I collect guitars. When I was a kid, I always wanted a lovely drumkit. But I could never afford one. Now I have tons of money and they keep giving them to me. It’s crazy. So I collect guitars. I have a reasonable collection of very old Fenders. I love Fender guitars. I actually get more pleasure out of looking at the guitars than I do the drums. I do, however, have a room full of drums at home. This is all probably sinful to say since this is a Modern Drummer interview, but it’s true.

RS: Do you ever exert pressure on yourself to sound better than the night before, or set out to outdo your efforts in the studio, or are you beyond that sort of thing?

RT: I used to do that. But I think I’ve matured in that I concentrate on the overall sound of the band now. I know when I play well. On tour, I constantly have to play well. If I have a bad night, I feel terrible about it. But usually I can kick myself to get it together even when I’m not having a great night. But my main thing is to look at the effect the whole band is having on the audience. I’m really more concerned about that than anything else. That’s the most important thing when you really get down to it.

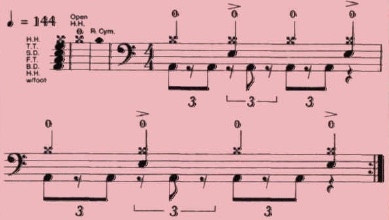

Drumming: Taylor-made

Roger Taylor’s drumming is one of the major factors in Queen’s success. His style can be characterized as straight and strong, yet musical and clever through Queen’s intricate rock arrangements. The examples below demonstrate Roger’s work on some of Queen’s major hits, along with an excerpt from his current solo album. Advertisement

- “Bohemian Rhapsody” (final sections)—Queen; A Night At The Opera, Elektra 7E-1053, recorded 1975.

- “We Are The Champions”—Queen; News Of The World, Elektra 6E-112, recorded 1977.

- “Bicycle Race”—Queen; Jazz, Elektra 6E-166, recorded 1978.

- “Another One Bites The Dust”—Queen; The Game, Elektra 5E- 513,recorded 1980.

- “Radio Ga Ga”—Queen; The Works, Capitol ST-12322, recorded 1984.

- “A Man On Fire”—Roger Taylor; Strange Frontier, Capitol 4X1- 12357,recorded 1984.