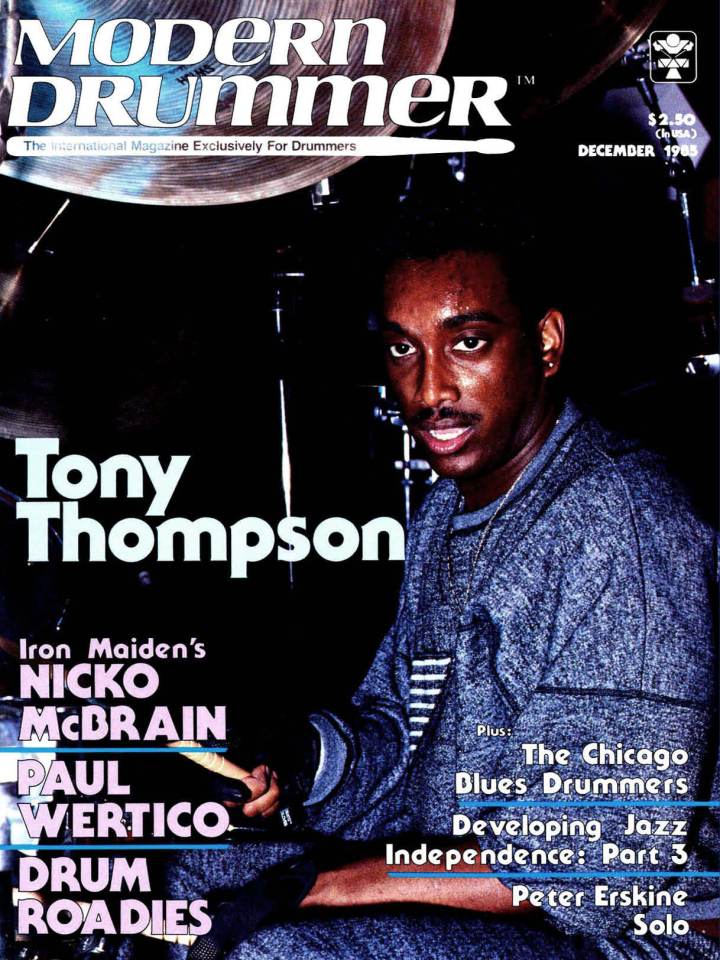

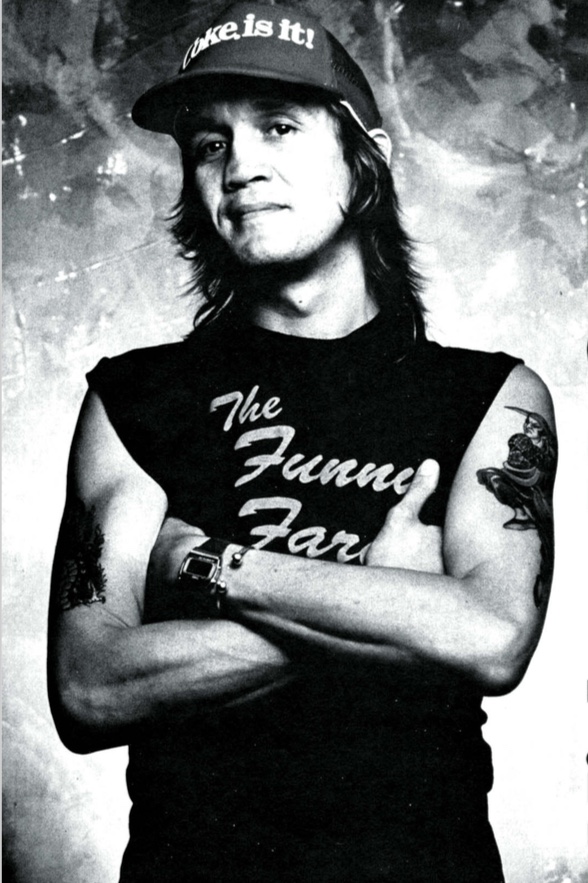

Nicko McBrain — Heavy Metal Perfectionist

Iron Maiden’s Nicko McBrain may refer to himself as “The Thrasher,” adding that he has “no coordination” and “no technique.” Don’t believe him for a minute! Being as modest as he is about his talents, McBrain won’t tell you that his work on Maiden’s recent LP Powerslave, is some of heavy metal’s most definitive drumming. You’II just have to hear for yourself, as McBrain’s love for raw power and aggression drives him to perform with machine-gun precision.

The roots of McBrain’s talents go beyond heavy metal drumming, although he admits that he knows that he will always be associated with the thunderous sounds that he brought to heavy metal when playing with Pat Travers and, now, Iron Maiden. Although this is not well known, McBrain got down to funk grooves when playing in Jim Capaldi’s band in the early ’70s, and when jamming with friend Ted McKenna (who’s known for his roles in The Alex Harvey Soul Band and in Greg Lake’s recent band). McBrain cites his earliest drumming hero as being Joe Morello and explains that, although he plays what he terms “power music,” he has “a jazz feel.”

At age 24, McBrain was cited by England’s Melody Maker as playing in the vein of John Bonham and Keith Moon. McBrain calls that the greatest compliment that was ever paid to him. And it’s no wonder these kind words were written about him. With McBrain, the famous Keith Moon lunacy is definitely apparent, both on stage and off. If you ever have the opportunity to catch one of McBrain’s live performances, you’II see that he does have the overwhelming visual and aural impact of, say, a legendary rock player such as Moon or Bonham. Off stage, although McBrain has a very professional attitude when it comes to drinking and taking care of his health when he’s on the road, he has a zany sense of humor and a laugh so loud that it’s nearly deafening. “I’m a lunatic. You’ve got to be a little crazy to want to bash things all the time and make noises,” he laughs. Advertisement

Even if metal drumming isn’t your cup of tea, you’ve at least got to respect McBrain for being the backbone of the largest rock tour ever. Period. When Iron Maiden finished their World Slavery Tour, they had performed almost 300 concerts in 28 countries over a 13-month period. (And that’s not easy when each show featured their full Egyptian-concept stage production, which was transported in six 45-foot articulated trucks—along with a massive stage set with 120,000 watts of P.A.!) McBrain will be the first one to admit that he was physically exhausted, but in the true drumming spirit, he flew to major cities in Japan and Australia after the tour was completed to promote his specially designed Sonor concert kit.

McBrain’s perfectionist attitude toward mastering his craft has barely left him time for his second love, aviation, or to watch his two-year-old son practice on his Smurf drumkit. But fortunately, he was kind enough to take time out before a sold-out, 35,000-seat outdoor venue in Phoenix, Arizona, to speak candidly with MD. Here are the interesting results.

AR : Why did you choose to play the drums in the first place?

NM : Basically what happened was that, when I was 11 1/2 years old, there was a TV show with Dave Brubeck on it. He did “Take Five” with Joe Morello on drums. Morello did a solo and I thought, “This is what I want to do!” So, I went straight into the kitchen, took two knives out of the cubbyholes, and started beating the shit out of the stove, the washing machine, and anything that I could make noise with. My mother and father came out screaming, “What are you doing?” The paint was chipped off everything, and the wood was all ripped up. Advertisement

It started from there. The very first time that I thought about it or dreamed about it was after I saw Morello on television. My father was into jazz. I think I got my talent from him. He used to play the trumpet during his early life and as a teenager. Then, when the war broke out, he got into aviation, and got into an accident. He lost a lung and had to stop playing the trumpet. He has a keyboard now—a bloody great one. It has a rhythm section—everything but the kitchen sink! Anyway, music runs in the family. My grandfather on my father’s side was an entertainer/comedian on the semi-pro level, so I had a lot of encouragement from my father.

For a year, I played with knives and biscuit tins. Then, I started using my mother’s knitting needles as drumsticks, and she went completely bananas! I drove her mad. Well, a little later, my father and mum asked me what I wanted for Christmas. I said, “I want a drumkit.” My parents weren’t the wealthiest people, and in those days, drums and equipment were very expensive. They still are, aren’t they? So, they bought me a kit a year later, when I was 12 1/2 years old. It was a Broadway John Gray kit. They don’t make them anymore. They were made about as well as Ajax. Oh, this is giving my age away, isn’t it? [laughs]

Anyway, I got my first drumkit on the Christmas before my 13th birthday. My parents said, “This is going to be a five-minute wonder if we ever saw one!” And I said, “No, you’re wrong!” My father said, “I think so, too.” I’ll never forget that. Advertisement

My mother always wanted me to go to college and have a trade, but I was playing in bands. The first gig I did was two weeks after I got this drumkit. I met these guys in secondary school—a guitarist and a singer who thought he was Mick Jagger—and we did a gig at the Russell Vale School Of Dancing in Woodgreen, London. You might well ask why a school of dancing. Well, I had to go to ballroom dancing when I was a little boy. It was one of the things my mother wanted me to do. It was a gig, anyway. They paid us ten Cabbage Flake chocolate bars each. I kid you not; this is very true! We stole about eight boxes as well, [laughs] The guitar and vocals were going through the same little amp sitting up on a chair.

Seriously, though, I always knew that I would be a drummer. It suits my character. I’m a lunatic. You’ve got to be a little crazy to want to bash things all the time and make noises—you know, clank-clank, bang-bang, wallop-wallop. So, it just developed from there, and since my professional career began, which was 11 or 12 years ago, I haven’t looked back. I’ve had some problems, but if I had to live it all again, I definitely would.

AR: What bands were you in prior to joining Iron Maiden?

NM: Before I joined Maiden, I was in a French band called Trust. I did various French tours with this band. Before I even knew Maiden, this band Trust supported them. They had Clive Burr, a very dear old friend of mine. During a tour, both bands became very close. There was a mutual respect and friendship between the two bands. Then Iron Maiden left to do a second Japanese tour, while I did an LP with Trust. But I had problems with the band— circumstances which led me to leave. I had lots of problems with business and attitudes—part of the problem being that they’re French and I’m English, which says it all. One day, I got a phone call. Clive said that he wasn’t happy with Maiden, and that they weren’t happy with him. After four more months—Christmas ’81—it all came to a head, and that’s when I came in. The ironic thing was that, after Clive left Maiden, he made an album with Trust, so we literally played musical chairs. Advertisement

AR: Have you always been in heavy metal bands? If so, where do your jazz influences fit in?

NM: I do have a jazz feel. I have always appreciated the big bands—Krupa’s stuff and Buddy Rich’s stuff. Well, Joe Morello was the one who turned the spark into a fire. When I was a kid, my father was always writing to people like George Shearing, Benny Goodman—people like that. So, I’ve been around it. There was always a bit of influence. I grew up with Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, and The Beatles, to name a few. Then Vanilla Fudge and other groups came along that influenced drumming and music in general.

Ever since I started playing, I was a thrasher—no coordination, no technique, just thrash, thrash, thrash and power. I’m a very thin person. I just have the ability to smash the hell out of a drumkit. That’s the way I’ve always been. At the early stages of my career, I used to audition for local pub bands and pop/rock bands doing cover versions of hits, but I was always being told, “You’re a good drummer, but you play too loud. “And I’d say, “Well, tough for you, man. Turn it up!” In no way would I allow myself to be directed by any of this. I said, “This is my style, and that’s it.” I was always into the raw power. I never tried to discipline myself rudimentally. I’m not a really fine technician. I mean, I’ve got speed and can coordinate things, but I’m not real perfect. I mean, my time slides up and down a bit. I’m not a metronome like Steve Gadd is, or say, Simon Phillips or Sly Dunbar. You know, those guys are excellent with that. I can do it. I have done click tracks before, but it can be a bit of a problem sometimes. But style-wise, I mean, one of the first bands I played with was a group named Streetwalkers. It succeeded the band called Family with Roger Chapman and Charlie Whitney. These guys were rock ‘n’ roll with a touch of funk in it. Well, it had an element of everything in it. It wasn’t heavy metal, although it was power-driving music. It was a drummer’s dream. It was a different style for me.

I even played with Ronnie Lane on one session when I auditioned for his band. I had a nine-piece Hayman drumkit with about nine cymbals, a couple of rides, and six or seven crashes. The first thing Ronnie said to me when I set my kit up was, “You aren’t going to play all those, are you?” [laughs] He said, “What do you need all those for?”—because it’s a different style of music. Ronnie Lane’s style is like country folk/rock. Advertisement

I’ve also played with Jim Capaldi’s band; that isn’t heavy metal. I do like to get down to funk grooves. I feel that I’m not just a heavy metal drummer. I’ve done things that you would not believe are me. I mean, I sold my soul for a little while just to make some bread. It wasn’t what I really wanted to be doing. I just always wanted to play power music and to be an aggressive drummer. I’m an aggressive sort of person. That’s my nature, and that’s the way I play. My style hasn’t really been molded on anybody in particular. The only two people I can say are Bonham and Moonie. Now, I’d hate to try to categorize myself— who I sound like and who sounds like me. There are so many brilliant drummers around—young guys. I look at them and say, “Gee, when I was 22 I knew I was good, but these guys are serious!” The classic example is Tommy Lee. He’s brilliant—a fine drummer. He is like I was when I was his age. But that was my style of drumming—always has been.

AR: Would you guest on an album that wasn’t by a heavy metal artist?

NM: If somebody asked me to guest on an album, I would and it wouldn’t necessarily have to be heavy metal. It’s not likely that somebody would, because people think Iron Maiden/Nicko McBrain, Pat Travers/Nicko McBrain—heavy rock ‘n’ roll. But that’s the path I’ve taken, and that’s the way I’ll go until, God forbid and touch wood, my health diminishes or whatever. The day I can’t take any more will be the end—not the end of my life, but the end of my career. People have asked me what I will do when I get to be an old man. In terms of the age limit in rock ‘n’ roll, when it gets to the point where I’m too old to want to tour anymore, I’ll get myself a big band—not too much into jazz, maybe into blues, maybe rock ‘n’ roll with brass. This is for the future, and as I said, the only way that would stop would be if, God forbid, something happened to my health, or by some act of God, I couldn’t carry on with my career.

AR: Has touring taken its toll on you yet?

NM: Touring kills me every night. Now, I’m physically dying. Let’s put it this way: I feel like I’m dying, [laughs] I mean, it’s been such a heavy tour. This tour has gotten to us now, and I sort of punish myself. It’s a very punishing sort of music to get into. It’s very enjoyable at the same time, but when you do it every night for eight or nine months solid, you become very, very tired. Advertisement

AR: Well, it’s especially that way for a drummer. You have to be the most physically fit member of the band. How do you take care of yourself, especially on the road?

NM:I make sure that I eat at least twice a day. I have breakfast wherever I am, even if I have to make it McDonald’s. At least it’s something inside me. I might leave a hotel at 1:00 in the afternoon and go to sleep on the bus. I get into the hotel at 7:00 or 8:00 in the morning from the night before. Sometimes it’s not possible to get into a restaurant in a hotel or wherever to have breakfast, so I have to find an alternative. I usually have steak and eggs, or something like that. Normally, I eat two hours before a show and then after a show. We usually have steak, spareribs, and beans, but unfortunately, we can’t get good, wholesome cooked vegetables every time, every day. That’s the only problem. You have to have a staple diet. That’s one of the key things to survival. You can survive without a lot of sleep, unless you’re down to only two or three hours a night. I know my limit is five hours a night. I get up and feel like a bear in the morning after only five hours, but half an hour after I’m up, I’m fine. I can carry on a day’s work and perform without feeling totally out of it before I perform. Afterwards, it’s a totally different story, but I make sure I eat twice a day. Also, I try to get as much sleep as I possibly can. So, I have to take the partying as it comes, and sometimes I have to leave it, but the parties are when I run into record company people, business people, and competition. The last thing I want to do after a show is to stay up for two more hours. I like to go back to the hotel, and put my feet up or go to bed. Looking after yourself is important, and that makes for a comfortable inner feeling about yourself. People can work together more easily when they’re taking proper care of themselves. Not taking care of yourself does affect your playing. There’s a lot of discipline involved, besides the discipline you have when you’re behind your drumkit. You can let your hair down two or three nights in a row, but if you go for a fourth and you know you shouldn’t, you’re messing things up for four or five other people. And then you’ve got the audience. You can’t let thousands of people down.

AR: You don’t totally abstain from drinking.

NM: No. I’ll have a couple of beers. I might have a drop of tequila and orange juice, and go completely wild on that. No, I don’t completely abstain. You can’t become a monk. There is a time to party, but what I’m saying is that there is a right time and there is a wrong time. Nine times out of ten, it usually is the wrong time. You have to say, “Okay, I can take this in moderation.” My job is physically demanding, and I’ll feel bad the next day. Although I’ll still give the max and still give a good performance, when my chops aren’t quite together, I’ll say, “Man, I just blew that.” Someone else might say,”What?” Being a drummer is such a personal thing, even if you’re not much of a technician. As I said, I’m not really a technician, but I’m a perfectionist. I don’t like to make mistakes. So, if I go out the night before and make some mistakes, it makes things that much harder. At the moment, I feel really physically drained. The past week, I’ve really stopped late-night drinking. After shows, I go to bed, relax, and get room service for days. My room service bills have been astronomical! [laughs] You have to stay healthy in spirit and mind.

AR: Do you use any electronics?

NM: Electronics? In a word, no. In another word, none. In another word, never again. There’s a big argument going on in the business over the pros and cons of electronic drums. Frankie Banali, who’s a very, very dear friend of mine, has a gift for me that I’m waiting for. It’s one of those pads with a little memory or whatever you call it—a brain. I said, “Frankie, I never thought you’d get into this stuff.” And he said, “Neither did I until I tried it.” So really, I can appreciate that point of view. You can’t knock something until you’ve tried it. But I have tried it. In this studio in Geneva, this guy came up to me, and said there was this brand-new kit I should try out. I didn’t understand it at all. The thing just didn’t feel right. I said to the guy, “I feel like I’m playing pieces of plastic. This feels like playing on the tabletop I used to play on in my mum’s kitchen. They don’t feel right. There’s something about them.” Now, people who are into them will argue all night. Drummers who aren’t actually drummers can program these things to do phenomenal things. Yet these people just couldn’t sit at the drumkit for their entire lives, and play what they played on a machine. By all means, program an electronic drumkit, a Linn machine, or whatever to do what a drummer can do, but don’t program it to do something that you can’t do. These people do that. People program machines to play 16ths. There are people with two bass drums who play pretty fast, but not that fast! Advertisement

I hate them! I hate the whole concept! I’m sorry, but that’s the way I am. If you’ve got a bunch of electronic junk out on stage, and the power goes out on you, what can you do? With my drums, I can carry the show to a certain degree. It’s entertaining. That’s my argument against it. I know it’s a bit weak.

AR: Please describe your current setup.

NM: I use a Sonor. It’s a 9-ply Sonor Phonic Plus kit. There are square-sized shells. They left the bottom heads off for me. I do believe my kit has beech-wood shells. They stopped manufacturing this particular drumkit—this particular line— about three years ago. They found that it wasn’t selling so well, but when I asked them to make me a concert kit, this was what I wanted.

I have an old XK 9212 model. It’s a kit I had in 1979, which has standard concert toms. The head sizes are 6″, 8″, 10″, 12″, 14″, 16″, and 18″. I use a 24×18 bass drum. The old kit has a 24x 14, so I have an extra 4″ on this bass drum, which makes it super. I asked Sonor to duplicate my old 9212 kit, and this is what they gave me, which is not what I asked for, but I’m ever so pleased about it. They said, “Well, we made it for you, but we left the bottom heads off it.” And I said, “Oh, that’s a nice little touch.” Advertisement

I have used Sonor since the first kit I had after my father bought me the Broadway kit. It had a 20″ bass drum, a 16″ floor, 13″ hanging tom, and a little 4 1/2″ snare. I was first introduced to Sonor a long, long time ago, and then when I was with Pat Travers, I approached them to do an endorsement. They didn’t want to do a 100% thing. They gave me a kit at factory cost, which in those days was ridiculously cheap.

The next kit I got was exactly the same, which was the one I was describing that I wanted Sonor to duplicate because it was the old model. They changed the fittings. They revamped the hardware. So I said to them, “Well, look.” They built a white kit for me last year. It’s exactly the same, in the square shells, but with the bottom heads on—twin heads. That was a lovely kit, but the problem with it was that it was a difficult kit to mike live. I’ve never used it in the studio, oddly enough. I know it would be good, but the problem is that you have to mike over the top for the twin heads. You get more sound response from the top skins.

My cymbal setup is very close to the actual vicinity and area of the skins, so to look at my kit, you’d wonder how the hell I hit the drums. There’s not a lot of the drum showing around my ride cymbals, you know. So to mike the drums up, you get too much spillage, even if you try to gate the cymbals or gate the tom. It just doesn’t work. We talked about it, and I said, “I’ll go back to a concert kit for live performance,” which is why they designed it in the first place. Apart from that, the single-headed drums have a little more volume to them. You can get some really sweet sounds out of them. So, that’s what I’m with at the moment. Advertisement

All the hardware is Signature Series, which is the top of the line from Sonor, and the best in the world, I might add. I mean, Pearl and Tama have similar kinds of stands and hardware—very solid, very heavily chromed. A lot of people just dip it once in a zinc or a copper base, and then put chrome on that. That’s what chips off. This is expensive stuff. This is the Rolls-Royce of drums and hardware—the cream.

Apart from the fact that the sound of these drums is amazing, I use a Ludwig Super Sensitive snare drum, which I bought in Manny’s Music in 1974. I’ve had this drum for 11 years. It’s brutal. I call it “The Beast.” When you get it tuned right, it is a phenomenal drum. I’ve used a Ludwig Speed King bass pedal as well and always have. I will never use anything else. I’ve used different kinds of things, but I’ve always gone back to the Speed King and my Ludwig snare drum.

Anyway, Sonor at the moment is manufacturing a free-floating snare for me, because I tried out the Pearl free-floating snare system, and that was a brilliant drum. One problem, though, is that every time you use a Pearl free-floating drum, halfway through the show, the skin ripples very badly around the main beating area, no matter how much you tension it down. The more you do that, the more the tone goes up in the drum, which can become a problem. You can only do one show with that drum. I mean, on other drums, you can get three or four shows out of them before the tension of the skin is completely gone and it won’t stretch anymore. But at the moment, Sonor is developing this free-floating snare drum, so I might go with that instead of “The Beast.” Advertisement

AR: And what about your cymbals?

NM: Cymbals—I buy Paiste. Cymbals are very, very personal to me. I play a combination of Rudes, 2002s, and Sound Creations. So, I’ve got quite a variety of cymbals, a couple of which are really more or less for show. You see, I’ve got a couple of Color Sounds in the back, which are really just for visuals. Maybe once or twice. I’ll use the left-hand side one, and maybe eight or nine times I’ll use the right-hand side one, because the left-hand side one’s a bit hard to get around to. [laughs] I’ve also got a 40″ symphonic gong. It’s badly dented, because I’ve beaten the hell out of it. You don’t do that. You’re supposed to caress it; it’s a symphonic instrument. Someone from Paiste said, “Let’s send it back to Germany after the tour and get the dents beaten out of it for you.”

There is a certain way to play cymbals if you don’t want them to crack. If you want them to last longer, there is a certain angle of attack, and mine are towards me at an angle now. I’ve had to turn them a bit lower towards me over the years. I’ve finally got it to the stage now where I’m not cracking as many cymbals as I used to. It depends on the way you exert the initial force. If you strike against the edge and straight across it, the force is going to go right into the center spindle of the stand, and all the force will go down and be heated through the bell, back down into the edge. It doesn’t let the cymbal wobble, which is how the sound is generated from a cymbal. It’s got to have that movement. It’s got to bend. If you hit it a certain way, it’s going to put weird stresses on your cymbals. The cymbals work harder the longer you have them, and they’ll tend to crack if you keep hitting hard. I’m still hitting them as hard as I was, which proves that the way you set your cymbals can make them last a lot longer, especially Paistes. They’re not as robust as Zildjians.

[Drum roadie Steve Gadd—no relation to the famous Steve Gadd, although he is a drummer—gives the complete details of McBrain’s cymbal setup going from left to right on his kit: a 17″ 2002 crash/ride, a 19″ 2002 medium, a 16″ Rude crash/ride, a 20″ Color Sound, an 18″ Color Sound, a 22″ Sound Creation, a 20″ Color Sound crash/ride, a 20″ Rude crash, a 24″ Novo (China type), two 18″ China crashes, and a 40” China gong.] Advertisement

AR: What kind of sticks do you use?

NM: They’re a Foote C. What we have in England are A’s, B’s, and C’s. I was set with using this Foote C line 14 years ago. Before that, I used Olympic E’s. Then I found these Foote C’s, and I haven’t changed since. I’ve tried other drumsticks, but these are serious drumsticks. They last a pretty long time. They’ll actually wear out before they break. They’re made out of hickory wood.

AR: How many pairs do you go through a night?

NM: About a dozen—an average of ten pairs to a dozen pairs a night. On a very good night, I go through more. I used to have this trick of bouncing them off my crash cymbals, but it’s very dangerous, and with the way people can so easily sue you, you’ve go to be careful. There is always that one-in-a-million chance that it will spin through the air and knock someone’s eyes out. I once hit a girl in the eye and cut her eye up. She could have made my life very unpleasant if she wanted to, but she didn’t do that because it was a genuine accident. So, I’ve had to cool down on that. It looks great. Certain times, the lights will go out at the end of a song. The kids will see the drumstick flying through the air, think, “It’s mine,” and then—oops!—darkness. It’s tricky.

AR: Going through that many drumsticks a night must be costly.

NM: I buy them in bulk. I don’t have a free deal yet, so somebody out there better get sharp, lads! [laughs] These drumsticks cost around $3.00 a pair, which is still pretty cheap, but I buy a thousand pairs at a time. So, I’m putting out three grand a year, and sometimes more than that. The drumsticks are the biggest cost I have to incur. Advertisement

AR: What about your skins?

NM: I’ve used Ludwig Silver Dot Rockers. Bill Ludwig is a very good friend of mine, and he’s wanted me to use Ludwig for years. Haven’t you, Bill? We won’t go on about why or why not, but he’s always given me a very good deal with the skins.

Anywhere I am in the world, Ludwig always makes sure that I get a good deal when I need skins. But I don’t get free skins, and I don’t get free drumsticks. I get free cymbals. Right now, I’m negotiating for another kit from Sonor, but they want me to do a couple of drum clinics, which is fair enough. If someone wants to hear me rambling on about nothing, that’s fine, [laughs] I might be doing one in Tokyo, and I might be doing one in Melbourne or Sydney, Australia, just to reintroduce this line—my drumkit—back into the market. I think there’s been a lot of interest. People always compliment me on my sound, but there are two other reasons for that: our sound engineer, Mr. Doug Hall—who happens to be an extraordinary drummer and who never touches the bloody kit— and a P.A. system called Turbo Sound.

AR: Do you treat any of your drum sounds?

NM: I don’t treat any of my drum sounds. The only thing that we’ve done is gate the tom-toms. And all that means is that, as soon as I hit the tom-tom, I hear the note and then it closes off. It’s only activated when I hit the drum, so the gate snaps in behind to stop any spillage of any kind. I don’t get any snare leaking in the toms, I don’t get any hi-hat leaking into the toms, and I don’t get any cymbal through the tom-tom mic’s. Advertisement

AR: How are your mic’s arranged?

NM: I can’t go into the miking situation right now, because we’ve been changing them around. [An update from Gadd is as follows: SM56 Shures are used on all the tom-toms and the snare drum. M88 Beyers are used on both the bass drum and the gong. The overheads are KM84 Neumanns. RE20 Electro-Voices are on the tubular bells.]

AR: How much do you play when you’re at home?

NM : Hardly ever, strangely enough. The only times I really get to play are when I go out and have a jam with my mates, or go out to the clubs or pubs with my friends and have a blow with them. I always have sticks in the house. I tend to sit down for maybe 20 minutes and just beat the hell out of the floors. But that’s not very good, because my little boy copies me!

AR: Does he play the drums?

NM: Oh, he plays everything. He doesn’t really play. He’s only two years and two months. He picks up the guitar; he strums the guitar; he makes noises; he sings. He’s got a little Casio keyboard that he plays and he makes all these different sounds on—the violin, the viola. Then he’s got his little Smurf drumkit. I’m going to let Sonor put together a drumkit for him later on. They can convert a large floor tom or whatever. Advertisement

My wife got him a guitar and she said, “Do you mind?” I said, “Of course I don’t mind.” Just because I’m a drummer doesn’t mean that he has to be one. I don’t care. I prefer him to be a bloody keyboard player, actually. That way he’ll make more money than I ever will because he’ll be able to write songs. Drummers never get the credit that’s due to them in terms of arrangements and things like that. But to be a successful drummer, you’ve really got to work hard. It does help if you can write and sing. Phil Collins did it. He once asked me, “Would you ever get into singing?” I said, “I can’t sing. I haven’t got the voice.” And he said, “Well, that’s exactly the way I felt until I got into it and started singing. I can put all my ideas together and compose.” And look at him now. He hasn’t looked back, and I love the guy very much. Oh, this was way back in ’76 or ’77. In fact, it was before that. That was the last time I saw him and sat down with him. That was back in my Streetwalkers days. He had just done three nights at the Drury Lane Theatre in Covent Gardens. Genesis did three nights there, and he came out with an acoustic guitar. I don’t remember what song he sang. He said that he never felt so nervous in his life. I couldn’t believe it. It was my hero drummer sitting out there singing songs. And he told me, “That’s what you should do.” He established himself as a fine, fine drummer anyway, but if you’re looking for financial rewards for something like songwriting, it’s fine.

I think I’d encourage my boy to write songs if he wants to be in music. I think it does tend to make a little bit of difference in terms of discipline. But if he wants to be a drummer, he’s going to be, and that’s all there is to it. There’s nothing in the world that I can say to him to change that. He’s got to make his own way. Whatever he wants to do is fine by me. I’m not going to be mad if he ends up playing guitar, bass, flute, cello, or something. If he’s got a talent for something, he’s going to have it.