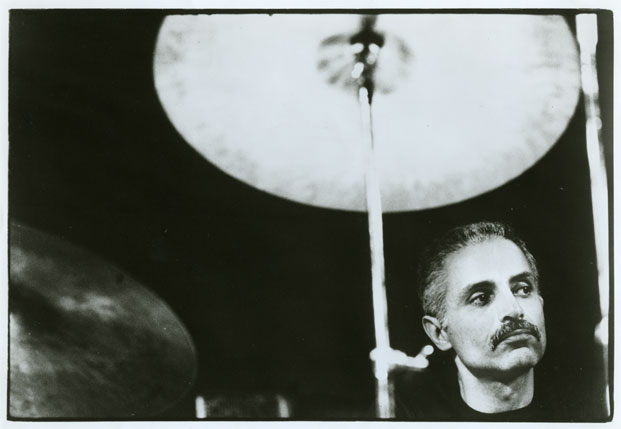

Paul Motian: Embracing The Past, Forging the Future

by Burt Korall

Following is an interview with post-bop master Paul Motian, which ran in the April 2005 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.

Paul Motian’s place in jazz drumming history is secure. His classic performances in the 1960s with mainstream modern pianist Bill Evans, or with highly adventurous and advanced artists like bassist Gary Peacock, trombonist Roswell Rudd, and pianist Paul Bley, are impressive. They document the drummer’s seemingly total lack of fear when it comes to taking chances.

Today, even at the age of seventy-four, Motian remains a key, major musical figure. The reason is clear. He’s never allowed himself to stylistically stand still, either as a drummer or a composer. Strongly motivated, Motian has continued to grow by remaining open to all kinds of music. And by insisting on not closing off any path of possibility—and getting sharply positive musical results—Motian is an undeniably hip role model for today’s developing drummer. He plays new and old things in a manner that is thoroughly convincing and true.

While most drummers his age have turned away from performing, claiming the need for rest or complete retirement, Motian remains deeply involved with the instrument. “Music is what makes life interesting and challenging,” he says. “If I didn’t play and compose, I don’t know what I’d do.” His latest release, I Have the Room Above Her, featuring Joe Lovano and Bill Frisell, is another excellent showcase of Motian’s formidable talents. And this is just the first of a number of recordings he’s recently made for ECM. Watch for two trio discs: one with Bobo Stenson and Anders Jormin, and another with Enrico Rava and Stefano Bollani. There’s also a recording of Motian’s Electric Bebop Band coming down the pike. Advertisement

Motian’s playing experience has been an uninterrupted, flowing, historical matter. And he believes playing and writing music is a matter of all you know. “All idioms are connected,” Motian insists. “My work as a drummer and composer has been affected by all I’ve heard and thought about.”

When asked about possible retirement sometime in the foreseeable future, Motian chuckles, as he has a habit of doing. Recalling Duke Ellington’s answer to a similar inquiry, he asks, “To what”?

Motian’s connection with music began early. His Armenian parents had originally immigrated to Philadelphia, where Paul was born. Then the family moved to Providence, Rhode Island, bringing their music with them.

“As a kid, Arabic- and Turkish-derived melodies and rhythms got me dancing around the parlor,” Motian recalls. His most important link to music, however, was established between the ages of twelve and thirteen. “I hung out with a drummer in the neighborhood,” he says, adding, “I listened to the guy practice and was completely taken with the instrument. I played the guitar briefly and quit. The drums had what I wanted and needed.” Advertisement

Motian initially became involved with swing and the big bands. He listened to Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, and Sidney Catlett. “Sid could create more music in four bars than anyone,” Motian recalls. Jo Jones’ approach with Count Basie, particularly his work on the hi-hat, left a lasting impression. A bit later, Motian became fascinated with Max Roach and Kenny Clarke, and he recognized the intense musicality of Dave Tough and Shadow Wilson.

Getting beyond the attraction to technical aspects of playing, Motian became increasingly involved with what drummers were saying when playing, how they went about projecting who and what they are. “Krupa was a show business icon; he played well and was quite visual,” Motian points out. “I loved Kenny Clarke. His beat was irresistible. And Max’s solos and the manner in which he played—how he related to the music—were certainly important to my generation.”

Out of great interest in music generally comes an intense need to learn as much about it as possible. Motian became a drum student and spent time in Rhode Island working with George Geer and Emilio “Yank” Ragusa, and in New York with Fred Albright, Eldon Bailey of the New York Philharmonic, and the widely admired Billy Gladstone, the famed Radio City Music Hall percussionist. Advertisement

“I went through a variety of drum instruction books, developing my hands and reading ability,” Paul recalls. “I did a lot of practicing and received the sort of training that is most applicable if you want to play with a symphony orchestra. I can’t say this sort of studying wasn’t helpful. It was. But my interests were elsewhere; they were in jazz.

“Lacking in my drum studies,” he continues, “was information regarding song structure, harmony, and things of that sort. I didn’t fill in those blanks until I started playing with all kinds of people.”

Motian recalls especially enjoying his studies with Billy Gladstone. “During the Korean War, when I was in a Navy band in Virginia, I’d come up to New York for lessons with Billy. He had unbelievable hands. They were almost perfectly controlled. He really knew the instrument. Many drummers came to the Music Hall specifically to see and hear him and went away thoroughly impressed. His roll was absolutely terrific. Billy liked jazz. He took me to hear Zutty Singleton, the great traditional jazz drummer, for the first time. I remember that!” Advertisement

Motian’s musical education included listening to countless recordings. It was part of the process of developing an acute awareness of what was going on in jazz. Going to hear music live was also crucial to expanding his knowledge of how to deal with the instrument.

When he was sixteen, Motian’s father bought him a car. Almost immediately the young drummer drove to New York for a weekend to make the rounds of the clubs. Motian fell in love with the jazz capital, hearing a lot of jazz on New York radio—most of it played by the famed jazz disc jockey “Symphony Sid” Torin. The primary excitement, however, was provided by the live music, for which there is no real substitute. The Dizzy Gillespie big band played opposite the George Shearing Quintet at Bop City, a club once called the Hurricane, in the Brill Building on Broadway. Motian was also uplifted by an all-star band including Miles Davis, Fats Navarro, Bud Powell, Max Roach, and others at a downstairs club, also on Broadway. Overall it was an adventurous trip.

Motian’s life continued to be obsessively centered on music. During the Korean War, he played in a Navy band. After being released from the service, he came to New York. The year was 1955. He studied at the Manhattan School of Music, but had to give it up because work began streaming in—first with the excellent jazz pianist George Wallington, then with almost everyone—Jerry Wald (where he met pianist Bill Evans), Tony Scott, Gil Evans, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, Art Farmer, Eddie Costa, Paul Bley, Thelonious Monk, Stan Getz, Morgana King, Charles Lloyd, and other interesting players, many of whom are identified with the so-called avant-garde, such as bassist-composer Charlie Haden, trombonist Roswell Rudd, and composer-theorist George Russell. Advertisement

Obviously there was something in Motian’s playing that appealed to players across the board. That “thing” was his ability to get deep into the music, simultaneously provoking and bringing a sense of comfort and relaxation to players, regardless of style or inclination.

“How I got to play with Monk for the first time was a fortunate accident,” Motian says. “I was living on Ninth Street and Third Avenue, and one night I dropped in at the Open Door, a club in the area. Drummer Art Taylor couldn’t make the job. So producer Bob Reisner asked me to play the session. I ran home as quickly as I could and got my equipment. I remember talking briefly to Monk. The subject of rushing tempo came up: ‘Hitting the drummer on the side of the head is an excellent cure for rushing,’ Monk commented.”

Motian’s need to play was so intense after he got to New York that sticks or brushes were seldom out of his hands. From the mid ’50s to the late ’60s, he played every day in a variety of circumstances. “Three hundred sixty-five days a year,” the drummer insists. That’s just one of the reasons for his impressive and wide-ranging résumé. He learned what to play and what not to play from some great teachers—from Roy Eldridge to Arlo Guthrie (at Woodstock), from Coleman Hawkins to Bill Evans, from Stan Getz to Paul Bley, from Lennie Tristano to Morgana King, from Mose Allison to Charlie Haden, from Joe Lovano to Charles Lloyd, from Bobby Hackett to John Coltrane, and from Bob Brookmeyer to Don Cherry. Advertisement

For all his diverse experiences in music, Motian is most frequently remembered for his work with pianist Bill Evans, particularly the trio featuring the extraordinary bassist Scott LaFaro. The trio was notable for three-way improvisatory interaction and a loosening up of the playing process. LaFaro became famous for his performances with that trio. His work was an extension, on a smaller instrumental scale, of what bassist Jimmy Blanton had done with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. The trio was also a major step forward for Motian. The group was no longer just a pianist and two accompanists. It was more like three equal individuals, feeding and inspiring one another.

Motian played quietly, commenting when he felt it necessary, playing his own “interpretive” version of time. He was making his way to his own view of ultimate freedom that would emerge in years to come with his own bands and with many advanced players.

After six years, Motian felt compelled to leave the Evans trio. “We played so softly, we were hardly moving,” the drummer says. “By this time [1964], Scott had died in an auto accident. And I needed more freedom and stimulation. So I left, although Bill pleaded with me to stay on.” Advertisement

Motian found what he needed in his own bands, and with musicians who thought the way he did. This is best documented on a number of ECM recordings—those Motian made with Bley and Gary Peacock, as well as pianists Marilyn Crispell and Keith Jarrett. Particularly of note are Jarrett’s Survivors’ Suite and At the Deer Head Inn, as well as four Motian CDs—Conception Vessel, Dance, Paul Motian—Rarum (selected recordings), and It Should Have Happened a Long Time Ago. Motian is brilliant throughout.

Motian has become internationally known for his “advanced” work as a drummer and composer. He is essentially a self-taught composer who works carefully until he achieves what he wants at the piano. “I’m not exactly Cole Porter,” he explains, chuckling again. “But I generally find what I’m going for.”

Everything he is doing both as a drummer and writer these days is an outgrowth of all he has done throughout his career. Motian makes records and works with a trio with Joe Lovano and Bill Frisell. He does dates with his Electric Bebop Band—put together “to destroy bebop,” because Motian felt there was no one around who could play the music. But the group turned out to be a far more positive experience than the negative one he had anticipated. The band includes two tenors, two guitars, drums, and electric bass. Motian also plays with other groups and individuals who aren’t ashamed of trying to move music in various interesting directions. The music might be difficult to assimilate, but it’s worth the effort. Advertisement

Paul Motian came to music in the years of bebop and has since played with people who preceded him on the scene and others who are a generation or so younger. It doesn’t seem to matter to him. It’s all just music, and he calls on multiple experiences and responds to all of it with no preconceptions as to how it should be played.

Certainly Motian’s career in music has been anything but circumscribed. What will he do next? Considering the evidence of over a half century, his work will not be retrogressive, or concerned with nostalgia. He will remain cutting-edge.