Ben Riley: Power of the Lion, Patience of the Ages

Story by Ken Micallef

Story by Ken Micallef

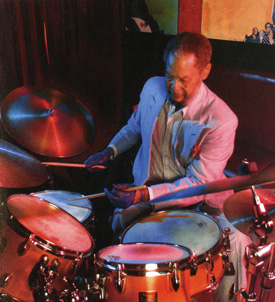

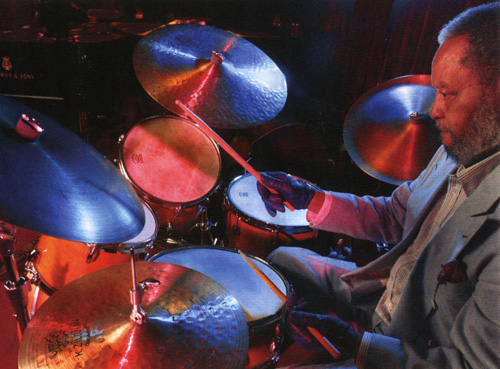

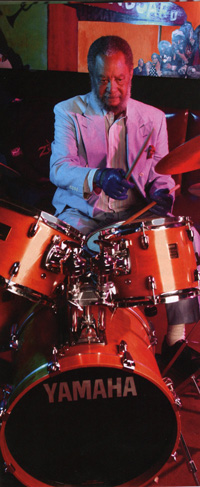

Photos by Paul La Raia

This article orginally ran in the February 2005 issue of Modern Drummer magazine. For access to all of the great editorial from MD’s first twenty-six years of publication, check out our Digital Archive.

At a recent reunion performance featuring members of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Ben Riley provided the rhythmic fire to the band’s hard-bopping melodic flash. Assembling at New York’s Iridium jazz club on the anniversary of Blakey’s birth (October 11, 1919), the Riley-led all-star group that included bassist Lonnie Plaxico, pianist John Hicks, alto saxophonist Bobby Watson, and tenor great Gary Bartz was finding its feet. While the musicians displayed strong conviction as soloists, the unison lines and group playing were less than perfect—at least at first. If not for Riley’s firm hand, the night might have devolved into a jumble of casual ensemble playing, missed cues, and irresolute endings.

Ben Riley commands respect from the moment he hits the bandstand. While he is best known (and beloved) for his years spent in Thelonious Monk’s quartet at the peak of that master’s powers, Riley has also recorded and performed with many other jazz greats. His flexible artistic demeanor and powerful time feel, coupled with a talent for finding unique solutions for practically every situation, has kept the drummer busy for the thirty-plus years since leaving Monk’s services. Advertisement

Riley’s résumé is a who’s who of jazz: Andrew Hill, Hank Jones, Barry Harris, Junior Mance, Nina Simone, Alice Coltrane, Abdullah Ibrahim, Barney Kessel, Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz, Chet Baker, Johnny Griffin, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and Sphere, the Monk tribute group that features some of Riley’s best drumming. All this from a musician whose first exposure to the drums was the marching brass bands he heard as a toddler in Savannah, Georgia.

Now seventy-one years old, Riley looks like a gentle lion behind the drums. His gaze falls somewhere beyond the audience as he concentrates, whipping the cymbals and jabbing the snare drum in constant motion. With the Messengers, Riley took a different tack for each soloist, applying unique colors to the musicians’ personalities and approaches.

Playing classic Blakey numbers like Wayne Shorter’s “One By One,” Freddie Hubbard’s “Up Jumped Spring,” and Benny Golson’s “Whisper Not,” the group shifted gears as Riley altered the groove. His drumming was fluid, soulful, and endlessly inventive. Behind Bartz’s roaring tenor, Riley drew a tart attack. For Watson, the drummer’s sound turned silky and streamlined. For Hicks, piano and drums became pointed and aggressive, matching melodic twists with muscular jabs. Advertisement

Throughout the night, Riley’s cymbals shifted from autumnally dark to bossa nova cool, from dry and hard to liquid and sensual. All of this out of two ride cymbals and a 21″ China. Occasionally leaning into the cymbals when extra punch was needed, Riley exuded all the strength of a ’70s Cadillac cruising with the top down, the road ahead serene, secure, and smoking.

Like all of the greatest musicians, Ben Riley is a storyteller. That holds true for his skills of verbal communication as well as his musical accompaniment. And his album as a leader, Weaver of Dreams, shows him to be just as resolute as his hard-touring band, the Ben Riley Group, is in concert. Though his energy has been slightly curtailed by bouts with diabetes and lung problems, Riley maintains a schedule as intense as any young jazz musician. No wonder Monk hired him without an audition, and ten minutes into the opening song of his first gig shouted, “Drum solo!” Afterwards, Monk nudged Riley, “How many people could have done what you just did”?

For sure, there is only one Ben Riley.

MD: You have been affiliated with so many leaders, and you’ve remained busy through the years. What are the elements of your drumming that keep you in demand?

Ben: I came up in an era of accompaniment. We all had to learn how to do it—not only solo, but accompany. I enjoy that more than soloing, because each person I’ve worked with has had different attitudes, songs, and styles of playing. It makes me very aware of trying to enhance whatever they are doing. I never come on a job thinking, “I’m going to play this or play that.” I wait to see what they’re going to do and then fit into that picture. Advertisement

MD: Did each leader bring out different facets of your drumming?

Ben: Yes. I had different styles to think about every time I played. When I came to work it was like going to school. I never knew what was going to happen next, so I was bright-eyed and bushy-tailed.

MD: How would you approach Junior Mance differently from, say, Johnny Griffin or Alice Coltrane?

MD: How would you approach Junior Mance differently from, say, Johnny Griffin or Alice Coltrane?

Ben: Junior and I worked together quite a bit. I could understand what he was going to do and anticipate different ways he was going to go. Griffin was more wide open because he wanted you to really flow along with what he was doing. With Alice, it was a totally different environment for me. Playing with her, I had to find a rhythm out of what she was doing and play that against whatever was going on.

I couldn’t stay in one place with Alice. I had to accommodate what she was doing. One of the hardest things I ever did was play some music of hers with the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra that they had already recorded. I had to overdub the drums after the orchestra had already recorded their parts. Advertisement

MD: Did they use a click track?

Ben: No. Alice gave me some clues about what she wanted to hear. The orchestra played in numbers rather than tempos. Their tempos varied between different sections and different instruments. So I had to find something that would fit all of the sections. It was fantastic. I also overdubbed on some things that John Coltrane had recorded without drums.

MD: I understand you were scheduled to record with Coltrane.

Ben: Yes, we were supposed to record as a duo just before he passed. We never got to it because he had taken ill the day we were to begin. We never had the opportunity.

MD: Then there is your work with Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and Johnny Griffin, the Tough Tenors. Your spirit really comes out on those records. You sound a little like Billy Higgins at times—not so much in what you’re playing, but in that positive spirit of the swing, that bounce.

Ben: Higgins and I interpreted a great deal alike. We liked some of the same people, like Kenny Clarke and Shadow Wilson. I started out playing a bit like Max Roach, but once I heard Kenny and Shadow, I thought that fit me a little better. I even played a little bit like Roy Haynes for a short period. Advertisement

MD: The Tough Tenors’ records sound so joyous and musical.

Ben: And that’s playing in three different styles. Junior played one way, Lockjaw played another, and Griffin played yet another. I had three different things to deal with, so it was always interesting. I had to be alert.

MD: You mention Junior Mance. Your album with him, Live at the Village Vanguard, is soulful and funky.

Ben: He and I developed a really good relationship in that band. We had played together in a trio before. I was accustomed to how Junior approached music. He was into a heavy Chicago blues style. He was even like Kansas City sometimes, with the rolling of the piano notes like Jay McShann. I played with him too.

MD: You also recorded with Duke Ellington [Solos, Duets, and Trios].

Ben: Yes, I recorded with five piano players on that recording—Duke, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Billy Taylor, Earl Fatha Hines, and, of course, my girl, Mary Lou Williams.

MD: I understand that you lived around the corner from Roy Haynes in New York for a while in the late ’50s, when you first started your career.

Ben: I lived at 148th right off Broadway, and Roy was at 149th. We became friends. That neighborhood was something. Billie Holliday was on 147th, and Mel Lewis was across the street. Many of the residents of Harlem moved up to what we called Sugar Hill. It’s from 145th to 155th. That’s where Manhattan starts to get more hilly. Sonny Rollins and Art Taylor came out of that neighborhood. Advertisement

MD: What one drummer had the biggest impact on your drumming in those formative years?

Ben: Kenny Clarke. I could be walking down 52nd Street past all the clubs and know which one he was playing in. I would sit at Birdland on Monday nights when Kenny was playing with Miles’ band. I’d stay there all night. Then when I got home, I would play, but I would interpret it my way rather than the way he played it. I was overwhelmed by Kenny, but I wanted to do it my own way.

MD: Back to the Tough Tenor records. You sound like you were all having a ball. How did that come together?

Ben: I was working with a lot of singers and piano trios at that time, including Nina Simone. I played with her for a year. Then I was up at the Newport Jazz Festival with Kenny Burrell and Major Holley, who I had worked with for a long time. Johnny Griffin came to the festival with no rhythm section, so he used Ray Bryant, Major Holley, and me. After that gig Griffin told me that he and Lockjaw had a band and he wanted me to be in it.

MD: Some of those tracks are very fast and quite long, and you play the standard ride cymbal pattern with no variation, which is harder than breaking it up.

Ben: When we played that fast it got to the point where I would not look at my hands. I just had to beef up mentally and not think about the tempo. Actually, playing with singers got me accustomed to singing melodies to myself. When I played very fast like that, I would always keep the melody in my mind so I wouldn’t be thinking of the tempo. Advertisement

MD: When we spoke with Bill Stewart a few months ago [August 2004 MD], he commented on how jazz musicians don’t play as many fast tempos as they used to back in the bop or post-bop days.

Ben: For one thing, it’s very difficult! [laughs] And with the freeform way of playing that most groups use today, playing fast tempos would be like going to war. You’d be clashing, because no one person is seemingly responsible for the time. Everybody is contributing their idea of what the song is supposed to be rather than keeping time. We used to do the same thing, but we would always mark beat 1 so everybody knew where we were. We also had a real sense of camaraderie. Today, a lot of the musicians don’t play melodically. They just play rhythmically, playing lines whether they fit or not.

MD: Is the lack of camaraderie among today’s jazz musicians due to the economy? Perhaps they don’t have as many US touring opportunities and can’t develop that closeness.

Ben: Back in the day, it would be nothing to see five drummers going out to hear another drummer. We always hung out together and exchanged ideas. I don’t see that today. That’s how the music became strong, because we all had our own approaches, and we shared them. Too many players today are being petty and thinking so much about money that they forget they are there to play.

Years ago, sometimes we only made ten dollars a night. But we were learning how to play—from 9:00 p.m. to 4:00 a.m.—and then we would go to an after-hours joint and jam and make some money off the tips. But we never put money in front of learning. The first thing that gets asked today is, “How much do I get paid”? They don’t ask about the music. Advertisement

MD: The knowledge drummers like you and Roy Haynes have is not always disseminated as it should be.

Ben: I just did a master class at Yale with Jackie Williams, Tootie Heath, and Ed Thigpen. We did a three-day master class and then a concert. We taught brushes, mallets, sticks, hands, and tambourine. We showed rhythm melodies from the drums. The audience didn’t want us to leave.

MD: What did you focus on?

Ben: I focused on the two different ways I use brushes. For the most part, I play brushes the same way I play sticks, except for the left hand, which I slide around for different sounds. I showed the students many brush patterns, like how I slide the left and right hands over and across. And I showed them Ahmad Jamal’s “Poinciana” rhythm, which is played with mallets.

I used to play with “pressure points” with my fingers, but after I got sick I couldn’t do it anymore—my fingers slide off the sticks. To do it today, I play with gloves to hold onto the sticks. Advertisement

MD: How do you use pressure points?

Ben: Rather than using the old arm-enforced technique, I snap my wrist and hold a brush or a stick a certain way with a certain amount of pressure to get a sound, almost like you would if you pounded down on the drum. I am not a pounder, but I can get a snap out of it that sounds like I am playing heavy.

MD: How did you develop that?

Ben: In the old days, staying in boarding houses and such, I would practice on pillows. I would practice every day on a pillow so no one would complain. That helped me develop my technique.

MD: Your drumming has a real sense of elegance.

Ben: I think of people like Sam Woodyard, drummers I watched when I was young. Or the way Max Roach would sit very elegantly, very correctly, and the way he played. So I emulated that. I took a little bit from each drummer that I heard. But I would never try to play something exactly like another drummer.

MD: How did you develop your determined, clear cymbal sound?

Ben: I worked in rooms on the East Side like Basin Street and the Astor Hotel lounge, where they only booked trios. This is back in the early ’50s. You couldn’t use sticks in those rooms—brushes only. The reason for this was you were set up right next to people having dinner. That’s where I met Ed Shaughnessy, Sonny Igoe, and Ed Thigpen. They were the only drummers allowed to play with sticks in those clubs, because they had such great control. I was determined that I would play sticks in those clubs too. My touch came from that experience, and I developed it by thinking and listening. Advertisement

MD: Did you learn to play very close to the head?

Ben: I found a way to touch the cymbals and the drums without scaring the people or cause them to drop their forks! [laughs] I understood that you didn’t have to bang to get a sound. Everything was very close, so one little short snap of the wrist would do if I wanted to play an accent. I also learned how to play with colors. I use three very different cymbals, and on each chorus I switch cymbals for the soloist, depending on his dynamics.

MD: Some of today’s jazz drummers still feather the bass drum and tip the ride cymbal. What are some of the other things that the drummers did when you were coming up?

Ben: Kenny Clarke would sometimes play four or eight bars and then accent one beat. That would give a little goose to the soloist and make him swing even harder. Shadow Wilson would play time and sometimes play almost nothing with his left hand, and yet the time felt so good you would want to get up and dance. Those things stay with you.

MD: Do you feather the bass drum at those really fast tempos?

Ben: Yes, although I don’t do it for as long as I used to.

MD: What is the key to feathering? It seems more felt than heard.

Ben: You don’t make yourself conscious of it, just like I mentioned earlier about playing fast tempos. Don’t make yourself conscious of the tempo. Make yourself conscious of the melody. And, of course, you have to listen to who you’re playing behind and anticipate what he’s going to do. If his voice rises, you rise with him. Advertisement

MD: It sounds like you’re listening more to the soloist than to yourself.

Ben: That’s it. And I always listen to the rhythm section. Piano is the full orchestra. The greater the accompanist is on the piano, the easier it is for me to play.

Thelonious Monk always said to me, “When you’re playing, you are listening. You might not like every song you play as much as the next guy. Whoever likes a song the most will be the strongest on it and he’ll have the best time, so play with him.” That’s why I always listen on stage to see who likes the song the most. That person will have the best beat and the strongest time.

MD: Let’s switch gears and talk about what it was like to go to Art Blakey’s legendary jam sessions in Harlem.

Ben: I would never ask to sit in at Art’s place. But when he was at 7th Avenue in Harlem, I would go early to watch. The more famous musicians in the neighborhood would play first. I remember when Philly Joe first came to New York and played there. When he finished, the house drummer whose gig it was wanted me to go up. I said, “No, this is your job, you go up. I’m not going up after that!” Philly fired those drums up and there was smoke coming up from them. But eventually, they started letting me play all the time.

MD: Is that how your career began?

Ben: My wife knew I wasn’t happy working at my day job, and she said I should give myself a year to see if I could get a playing career going. In 1954, right after the Korean War, I was working as a film editor. Well, I started getting gigs, and I haven’t looked back since. Advertisement

MD: Were there a lot of jam sessions in the ’50s?

Ben: Yes, all over town. I played in all the little clubs in Harlem, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Every borough in New York City had jazz every night.

MD: Did you practice for hours?

Ben: I would play along with records for hours.

MD: How did the leaders that you had longer tenures with—Ron Carter, Monk, Alice Coltrane, Abdullah Ibrahim—change your drumming?

Ben: Each had definite ideas about what they wanted to do, so I would take what they were doing and incorporate it into what I wanted to do. It was a matter of learning. I was the first drummer in Abdullah’s band. His music had all those African rhythms, and that was beautiful for me. I developed that and incorporated it into my style.

MD: Did you share more of a kinship with Monk and Coltrane?

Ben: Yes, but I learned from everyone I worked with. I learned about how to live. All that comes out in your playing. My mannerisms have developed from all of those life experiences. Working with and being around Thelonious was like attending a major music school. He gave me the opportunity to employ whatever I thought fit. If it fit, he would say, “That’s it.”

MD: When did Monk first see you play?

Ben: He first saw me at the Five Spot, where I was playing with three different trios. Thelonious would come into the club while I was playing, but he would go into the kitchen, so I didn’t know at the time if he was listening to me—but he was. Advertisement

MD: Did Monk say anything to you during your first rehearsal with him?

Ben: We never rehearsed. Monk just came out and started playing. He knew I would listen. He saw me sitting there every night at the Five Spot when his band came on. But he didn’t acknowledge me. He knew I was onto what he was doing, because I was listening. I heard him when he played with Trane, Shadow Wilson, and Wilbur Ware.

MD: So Monk asked you to come down…

Ben: He didn’t ask me nothing. His manager called and asked me to come down to Columbia for a record date. He said that they were waiting for me. After the manager convinced me this was true, I went down there. And Monk didn’t speak to me until after we finished the session. He said, “Do you need any money? I don’t want anybody in my band being broke.” I said, “Excuse me”? He repeated himself and asked, “Do you have a passport? You better go get it because we’re leaving for Europe on Friday.” That’s how I knew I got the gig.

We immediately went to the Royal Festival Hall in London. Everybody of importance was there. Limousines were double-parked outside. Monk began the show with a ballad, and in the middle of it he jumped up from the piano and said, “Drum solo!” It was frightening to see all those people sitting out there on my first show with Monk. But I did it. We went to the dressing room at the intermission and he said to me, “How many people could have done what you just did”? I had passed my first test. Advertisement

MD: Did Monk’s quartet ever rehearse?

Ben: When I asked Monk about rehearsals he said, “Why do you want to do that, so you can learn how to cheat? You already know how to play. Now play wrong and make that right.”

Ben: When I asked Monk about rehearsals he said, “Why do you want to do that, so you can learn how to cheat? You already know how to play. Now play wrong and make that right.”

MD: Did Monk ever give you any direction?

Ben: Once, after I played a drum solo with brushes, he asked me, “How did you know how to do that? You know it’s been done before, but how did you learn to do it”? Then he just walked away.

One day I started playing like Shadow Wilson and Kenny Clarke and he came up to me on the break and said, “Oh, you’re not playing that Roy Haynes shit no more.” I had listened to Roy play with him and had tried to do that, but it didn’t work for me. That’s when I knew that Monk wasn’t crazy like they all said. This man was listening to everything.

MD: How did you grasp his rhythmic concept?

Ben: I had listened to him for weeks before I ever played with him and thought I had it down. But when I got up there and he tapped off those tempos, it was totally different. He played in between tempos. Monk said most musicians could only play slow, medium, or fast. He played in between all of that. You could never predict what he would do. We would always play a song differently.

MD: Did that make it difficult for you?

Ben: No. It made me think more. I had to be open all the time. “Straight No Chaser” was different every night. I had to find something different to play. Because of that I developed patience. It was about learning what to do with space. Advertisement

MD: Do you ever listen to the records you made with Monk?

Ben: Yes, since I am now dealing with that music again in the Monk tribute band. The band is my band. It consists of some of the best players in town.

MD: What did you stress to them to get into the Monk spirit?

Ben: Play wrong. The more you try to play right, the more tension you have, so let it go. You have to make a mistake to be right. Play it as you feel it.

MD: What keeps you inspired?

Ben: I still go out to listen to people, especially young guys coming up. I never try to tell young people anything, unless they ask me. I don’t put myself in that position. Unfortunately, some of them think they know everything. But being around them keeps me inspired. I can still feel the juices.

MD: What do you look for in players coming up today?

Ben: I look for honesty. That’s the key to being unique. Be honest with yourself. Don’t copy. Let me hear you.