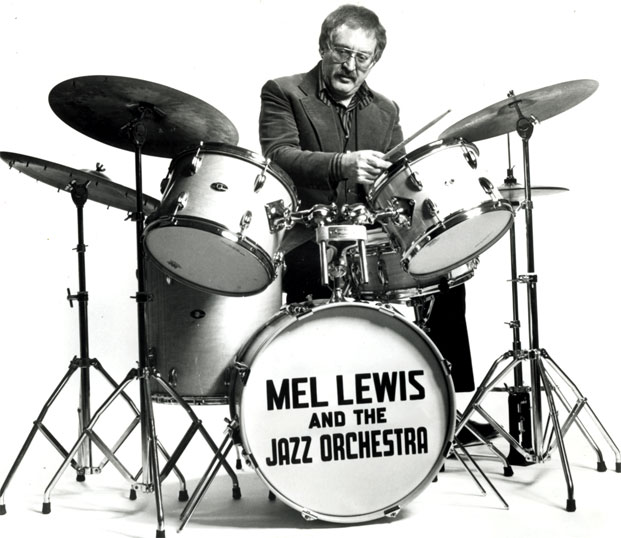

Mel Lewis: A Quiet Fire

This is an adaptation of the Mel Lewis In Memoriam article that ran in the June 1990 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.

Often, when Mel Lewis was playing with his Jazz Orchestra, he would break into this little smile. It wasn’t a “showbiz” smile like the one Jo Jones had, and it wasn’t like Louie Bellson’s enthusiastic grin, which seems to be there whether he’s playing or not. Mel’s was more subtle. You had to be very close to see it, and a lot of it was in his eyes. It was a look of total peace and contentment—the kind of look you might see on someone sitting in an overstuffed chair in front of a fireplace. For Mel, the drums were his easy chair and the band his hearth. He was the fire.

But it wasn’t a fire of bright, dancing flames. Mel’s fire consisted more of glowing embers that provided a permeating warmth—a cozy fire, but one with enough flickers of flame and pops and crackles to give you a start now and then if you started getting too comfortable. You never really worried about this fire getting out of control, but still, you wanted to keep your eye on it. It could surprise you.

Mel Lewis was known as a person who wasn’t afraid to speak his mind. He could come across as abrasive, especially in print, but when you got to know him you realized that there was nothing malicious in anything he said. He was just calling it the way he saw it, and there was often a twinkle in his eye that suggested he was being feisty on purpose. He loved music so much that he couldn’t let certain things go by without saying something that might cause others to give a little more thought to what they were doing. “Mel could be cantankerous,” Danny Gottlieb said on the night of Mel’s death, “but he had a good heart.” Advertisement

That came through in his playing. Lewis had a completely original approach to big band drumming, and the only reason he got away with it was because he played with such a sense of conviction. He knew he was right, and he made you believe it too. He wasn’t necessarily saying that other approaches were wrong, but because his was based more on supporting the band than on spotlighting himself, he was sometimes forced to prove that he was playing his way out of choice, not because he lacked ability. Granted, he would be the first to admit that a lot of drummers could wipe him out in a technique contest. But he often won on a more subtle level; next to him, many drummers came off looking obnoxious for playing too much.

Lewis often complained that to most people, “chops” meant “speed.” Mel could handle fast tempos just fine. But he was never one for blazing fills around the drums. For him, chops had to do with control of the instrument, a sense of color, and, above all, the ability to swing. “I learned that the power of the drums was in this smooth glide of rhythm,” he once told Stanley Crouch. “It wasn’t the volume.” Mel could play loud when the situation called for it, but he could also play very softly. A frequent comment about his band, and one that he was very proud of, was that they played with a wider range of dynamics than most big bands.

Lewis had a knack for choosing just the right cymbal to play behind each soloist, and he could get an amazing variety of sound from each cymbal as well. “I got my love of cymbals from Mel,” says Gottlieb, who was highly influenced by Lewis in his formative years. Mel, for his part, had the highest regard for Danny. I was once in a room with Mel and Buddy Rich, and Rich was saying that most of the rock drummers he knew of wouldn’t be able to sit in with a band like his or Mel’s and know what to do. “I know a couple of guys,” Mel responded. “Danny Gottlieb, for one. He can play that rock stuff, but I sometimes hire him to sub for me, and the guys in the band love him. He can play all the styles.” Buddy nodded. “That’s what you’re supposed to be able to do if you want to call yourself a drummer.” Advertisement

Mel could certainly play all of the styles, and as consummate a jazz musician as he was, he didn’t have an attitude about dance music. He was perfectly happy to play a wedding—ethnic dances, hokey-pokeys, and all. “Playing for dancers is great training for a drummer,” he told me. “It really teaches you to be consistent.”

Jazz, of course, was his greatest love, and he always had a standard question for me when we spoke: “You got any jazz drummers coming up in your magazine so I’ll have something to read”? But it was obvious that he read all of the articles, because he would often comment on something that a non-jazz drummer had said in an interview. And he had a more open mind than most people gave him credit for. A few years ago, in a DownBeat interview, while speaking of the importance of swing, Lewis said that he heard a lot of swing in James Brown’s drummers. This past October, Max Weinberg arranged for Mel, Joe Morello, and Danny Gottlieb to attend the Rolling Stones concert at Shea Stadium and pay a backstage visit to Charlie Watts, whom Mel had first met when the Charlie Watts Orchestra played in New York. And Mel himself did some rock dates in the ’50s and ’60s when he was doing studio work. I was amazed to discover that he was the drummer on “Alley Oop.”

But as open-minded as Lewis was about some things, on other matters he could be extremely inflexible. He absolutely refused to believe that anyone could swing using matched grip. He thought that electronic drums and drum machines were the worst things that had ever been invented, not because he was against technology, but simply because they put real musicians out of work. In fact, in an MD cover story in 1985, he went so far as to suggest that the company that made LinnDrum machines should be blown up. I couldn’t resist calling Mel when I heard that Linn had gone bankrupt. He took the news in stride. “That’s because they were making something that should never have been made,” he said. Advertisement

Mel’s own taste in equipment tended toward the traditional. He stayed with calfskin heads till the very end, going to considerable trouble and expense to obtain them. He loved old Ks and would lecture anyone who would listen about what was wrong with modern cymbals. (Briefly, they were too heavy.) His choice of equipment was so linked with his way of playing that it was sometimes difficult to separate the two. I remember speaking with Peter Erskine a few days after he had subbed for Lewis at the Vanguard. “I hadn’t intended to try to sound like Mel,” Erskine said, “but as soon as I sat down behind his drums and cymbals, a certain ‘Melness’ started coming out of me.”

Mel loved young drummers and did a lot to encourage them. But he never gave lessons as such. “I teach every Monday night at the Vanguard,” he often said. He would, however, invite young drummers over to his apartment to listen to records and discuss the music, or he would go with them to pick out cymbals or do anything else he could to help or advise them with their careers, such as hiring them to fill in for him at the Village Vanguard whenever he went to Europe. And from time to time he would call me at MD to suggest that I keep an ear open for some young drummer who was starting to play around New York. Danny Gottlieb, Joey Baron, Kenny Washington, Adam Nussbaum, Jim Brock, Dennis Mackrel, and Barbara Merjan were just a few of the many drummers that Mel did his part to spread the word about. He was definitely a father figure to many of them.

He treated this journalist the same way. Once, when he had asked me the usual question about upcoming jazz drummers in MD, I replied that I was hoping to interview Buddy Rich soon, but that I was having trouble getting in contact with him. “I think he’s in Europe, but that would be great if you could do an article with him,” Mel responded, and the discussion went elsewhere. A couple of weeks later, Mel called me. “I just spoke to Buddy and told him that you want to interview him. He said that he’ll be in New York at the Bottom Line in about three weeks, and he’ll talk to you then. Is that soon enough”? “Uh…of course,” I replied, my mouth hanging open. Advertisement

Not only did Mel arrange the time and place for the interview, but he even accompanied me when I went to do it. Although I had been interviewing drummers for several years by that time, I was intimidated by the thought of confronting Buddy Rich. But having Mel there put me at ease. The interview went great, and I’m sure that it was in no small part due to Mel having paved the way for me.

Buddy obviously had great respect for Mel. “Mel doesn’t sound like anyone else,” Buddy said, “and that’s the best thing you can say about any musician.”

Mel Lewis, whose real name was Melvin Sokoloff, was born in Buffalo, New York. He began playing professionally at age fifteen and worked with the bands of Lenny Lewis, Boyd Raeburn, Alvino Rey, Tex Beneke, and Ray Anthony. He joined Stan Kenton’s band in 1954, which brought him national attention, with several reviewers crediting him as being the first drummer to make the Kenton band swing. It also gave him a setting in which to develop his “small-group approach to big band.” Mel wanted to play more like the bebop drummers of the day, using ride cymbal more than hi-hat, breaking up the time, and dropping occasional “bombs.” That didn’t fit in with a lot of the swing/dance bands that Lewis first played with, but it was perfect for Kenton, with whom Mel worked for three years.

Lewis moved to Los Angeles in 1957 and worked with the big bands of Terry Gibbs and Gerald Wilson, and with pianist Hampton Hawes and trombonist Frank Rosolino. He also co-led a combo with Bill Holman. In 1962 he made a trip to Russia with Benny Goodman. Advertisement

He returned to New York in 1963 and worked with Ben Webster and Gerry Mulligan. In 1965, Lewis and trumpeter Thad Jones (Elvin’s brother) formed the Thad Jones–Mel Lewis Big Band, which began a steady Monday-night gig at the Village Vanguard in New York City in February ’66. They also did a lot of recordings and tours, including a trip to the Soviet Union in 1972. In 1978, Jones left the band to move to Europe, but Mel kept the group going, calling it the Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra.

One of the most distinctive features of the band was its emphasis on soloists, who were always given plenty of room to stretch. Hearing the group live was often like hearing two bands in one. “It’s only a big band when everybody is playing together,” Mel told me once. “When someone is soloing, then it’s a quartet.”

A couple of years ago, Mel was diagnosed as having melanoma, a form of cancer that tends to turn up in various parts of the body. It started on his arm, then hit his lungs, and eventually went to his brain. But whenever I spoke to Mel over the past two years, he was always optimistic. On several occasions he declared that the worst was over and that he was on the road to full recovery. He joked about looking like Kojak when chemotherapy treatments caused his hair to fall out, but whenever the treatments ended, he would boast that his hair was starting to come back, and that doctors told him it would be thicker than before. Advertisement

Mostly, he was determined to keep playing, and he did. He made several trips to Europe during the past two years and did a number of recordings. At the first Buddy Rich Memorial Scholarship Concert, held on Long Island in April of 1989, Lewis received the first Buddy Rich Lifetime Achievement Award. The following October, Mel was honored at a concert by the American Jazz Orchestra. This past January, he did a clinic and performed with his band at the NAJE convention in New Orleans—against his doctor’s advice. “I have to show those people what a real band sounds like,” he told Adam Nussbaum. It was his final performance.

Lewis’s gig at the Village Vanguard on Monday nights was the most important thing in the world to him. The last time I spoke with him, in December, he had just come out of the hospital after a relapse, but, as usual, he predicted that the worst was behind him. “I’ll be at the Vanguard Monday night,” he told me. “I’m not sure if I’ll feel like playing, so there will be a sub on hand. But I’ll be there.” He died on February 2, just a few days before the band was scheduled to mark its twenty-fourth anniversary at the club.

When Village Vanguard owner Max Gordon died last year, many declared that it was the end of an era. In many ways it was, but as long as Mel Lewis was there on Monday nights, it wasn’t completely over. Now it is. Advertisement

Rick Mattingly