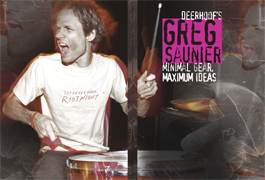

Greg Saunier of Deerhoof

by Mike Parillo

Deerhoof may be flirting more than ever with mainstream success, but its loose-limbed timekeeper isn’t about to start planning things now.

“When I’m playing, I feel like I’m speaking,” says Deerhoof drummer Greg Saunier. “I want to say things intensely and make it very clear, as if I’m trying to get a point across–and of course there is no point. It’s just music.”

Yes, it’s just music, but it’s not just any music. Deerhoof, which Saunier formed in San Francisco in 1994 with now-departed guitarist Rob Fisk, creates a uniquely heady mix of the guttural and the intellectual, the cuddly and the confrontational. More specific description can be tricky, because the band, which once swelled to four pieces but is currently a trio (rounded out by Saunier’s wife, Satomi Matsuzaki, on vocals and guitars and John Dieterich on guitars), transforms its sound on each album.

There are some constants. Drawing from an array of influences–“The three of us couldn’t be more different in terms of our background,” Saunier says–Deerhoof dips liberally into melodic pop, thrashing punk-influenced indie rock, and even syncopated funk. Saunier has listened to lots of classical music and earned college and grad-school degrees in musical composition, and thus the band’s output bears certain hallmarks of avant-garde and orchestral work: whisper-to-roar dynamics, odd meters, turn-on-a-dime feel shifts, and a free-flowing sense of time. Advertisement

Onstage, armed with little more than a kick, snare, and some sort of cymbal–lately it’s been a remote hi-hat, but that could change–Saunier sits low and unleashes a torrent of frenetic energy on the modest setup around him. On record, he’s more of a mad scientist, capturing a flow of ideas in Deerhoof’s digital laboratory and then tinkering with parts, often for months, until the noble gases of imagination have solidified into finished pieces of music.

Onstage, armed with little more than a kick, snare, and some sort of cymbal–lately it’s been a remote hi-hat, but that could change–Saunier sits low and unleashes a torrent of frenetic energy on the modest setup around him. On record, he’s more of a mad scientist, capturing a flow of ideas in Deerhoof’s digital laboratory and then tinkering with parts, often for months, until the noble gases of imagination have solidified into finished pieces of music.

Friend Opportunity, released in January, again finds Deerhoof walking its beloved line between the accessible and the far out, with some tunes covering so much ground that they seem much longer than their compact running length. Matsuzaki’s playful melodies and words–often just syllables–help keep things light and airy on top, while down below Dieterich stabs at rich, dark chords and Saunier whips up dense percussion parts, some animated by cowbell and woodblock sounds, others seeming electronic in timbre.

We spoke to Greg just before he left San Francisco for an Australian and European tour. He mused expansively on Deerhoof’s “accidental” aesthetic and the virtues of using a small kit, and he described a way to practice that just might save you a few bucks on a rehearsal space. Advertisement

MD: Did Deerhoof have musical goals in the beginning?

Greg: No. It’s amazing how that’s stayed the same. It’s a bunch of accidents piling up. If we think we’ve gotten a good formula for how to write a song, or how to play, or just how to be in the band, that formula ends up getting destroyed the next day. It can’t be applied twice.

MD: When Satomi joined in 1995, she had zero musical experience. What made you want to play with her?

Greg: Well, how Deerhoof started was Rob [Fisk] and I played bass and drums in a grunge band in the early ’90s. The rest of the band suddenly quit and moved away–no warning whatsoever. We had shows booked, and either we could do free improvisation or play the bass line and drumbeat from our songs. We ended up doing a combination. As you can imagine, our parts were uninteresting on their own. And we decided to take over the singing, but we weren’t sounding too good. [laughs] We were flailing around and sounding wobbly and shaky. We needed a singer.

Satomi had just moved to San Francisco from Tokyo and was staying with a mutual friend. He played her our first single, which we had done as a duo. He said, “Do you want to join this band”? To her it just sounded like noise. And she was like, “Okay!” [laughs] He sent her over, and within seconds I knew it was perfect. She could follow what we were singing to a T. We were playing in this hyper, ridiculously exaggerated style, and she would sing the melodies in the exact opposite way–totally pure, without decoration or expressive signals. There was a tension between her being not expressive enough and us being way too expressive that made the music work well. Advertisement

MD: Are your parts tightly composed?

Greg: No. The composed version of the part is very simple, which makes it that much more possible to go any direction with it. There’s a part for each song, but I never really play it flat out. It’s different every time.

I grew up listening to The Rolling Stones so much that I have a deeply ingrained idea of composition versus improvisation–everybody recognizes the songs, yet it’s ragged and loose. There’s that sense that they’re still finding new ways of playing “Satisfaction” or “Jumping Jack Flash,” and Keith Richards still has this huge smile as if he’s finally found the right way of playing it, after how many thousands of times.

MD: You seem to have been paring down your setup over time.

Greg: Kind of, yeah. In about ’96 Satomi and I went to see The Roots. At the time, ?uestlove was playing a very small drumset. The band completely blew my mind, and he seemed to be the star of the show. It’s not because he has a huge drumset or does anything flashy. It’s the quality with which he plays, the way he tunes the drums, and the precision of his feel.

Advertisement

Greg: Kind of, yeah. In about ’96 Satomi and I went to see The Roots. At the time, ?uestlove was playing a very small drumset. The band completely blew my mind, and he seemed to be the star of the show. It’s not because he has a huge drumset or does anything flashy. It’s the quality with which he plays, the way he tunes the drums, and the precision of his feel.

Advertisement

From that point on I’ve gravitated toward playing just three sounds: bass drum, snare drum, and either hi-hat or cymbal. But I always switch stuff around. It hasn’t been just a subtraction year by year.

Abstractly, I love the idea of having just the low and the high–the bass drum and the snare drum. You hear that concept in percussion from all over the world, like a djembe or a doumbek. It can make a low sound, and it can make a sharp cracking sound. I love that dialog between the two poles. Also, in percussion around the world there’ll often be some sort of metallic or faster sound, something that’s more constant–chattering that happens between the low and the sharp sound.

If you use fewer pieces, you realize that any of them makes an infinite range of sounds, even by itself. I’d get confused if I had more–I’m already overwhelmed just reaching for something interesting to play. If I had a large setup and the music was getting stale, I could spice things up by hitting something else. But as soon as I took those sounds away, it forced me to think of interesting ideas rather than just cool sounds. It forced me to be more creative. Advertisement

For the rest of the interview, pick-up the August issue at a music store, bookstore, or newsstand near you or subscribe now.