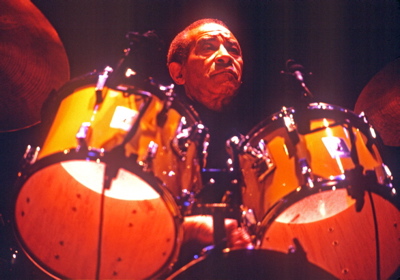

Max Roach

by Ken Micallef

Simply put, Max Roach brought jazz drumming into the modern age. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bud Powell revolutionized jazz with new melodies and concepts; Max matched these musical geniuses with startling rhythms and reactive, action-packed drumming that still influences drummers on a profound level today.

Parker and Gillespie played incredibly fast and complicated patterns on their horns, and Max followed suit by adapting their lines to the drumset, playing them across the bar line and deconstructing the rhythms among his four limbs. He brought a new sense of melody to drum solos that went far beyond the showy displays drummers before him inevitably relied upon. He, along with Kenny Clarke, moved the jazz drummer’s pulse, which had traditionally been on the bass drum, to the ride cymbal and the hi-hat, propelling the music with an unbridled and airy flow.

Max played with incredible speed, and he liberated the drumset from its purely timekeeping role, dropping explosive percussive “bombs” and exploring four-way coordination as no one did before him. He tuned his drums higher (than anyone previously), so as not to clash with the already turbulent front line of Parker and Gillespie. And he was an articulate speaker, socially driven artist, learned professor, and natty dresser to boot. Advertisement

To a greater degree than any drummer before him, Roach was an incessantly logical thinker whose drum solos and time-keeping had a decidedly intellectual edge. His sense of pace and timing was perfect, and his compositions, though grounded in hard bop, are forward-thinking vehicles that captured the imaginations of drummers as disparate as Bill Bruford and Jack DeJohnette.

In the 1960s Max would be on the front line of the fight against social and racial injustice. In the ’70s he founded one of the world’s first globally oriented percussion ensembles, M’Boom. Around this time he also frequently collaborated with avant-garde players like Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, and Archie Shepp. Max would continue to push the envelope in the ’80s and ’90s, with his highly regarded piano-less quartet and classical ensembles, not to mention appearances with hip-hop artists.

The December issue of Modern Drummer magazine features a significant number of drummers–young and old, jazzers and rockers–sharing their feelings about Max and his contributions to the art of drumming. So many drummers wanted to publicly thank and honor Max, in fact, that we just didn’t have room to include everyone. With a master player as multi-faceted as Max Roach, though, any insight into his work is welcome. In that spirit, we present half a dozen more drumming giants and their comments on history’s most modern drummer, Max Roach. Advertisement

Gregg Bissonette

Maynard Ferguson, David Lee Roth, Spinal Tap

Max was one of my biggest influences. My guitar player friend Carl Verheyen toured with Max years ago. He told me that one night Max said, “Carl, you start this tune off by yourself, and then I’ll come in on the second chorus…but make it fast!” After Carl played the first chorus by himself at what he thought was a really fast bebop tempo, Max came in boppin’ at a tempo way faster than the one Carl picked. After the set he said to Carl, “Man, you call that tempo fast?!” Carl said that Max’s idea of a fast bebop tempo was blistering.

I had the great honor and privilege to take lessons from and become good friends with Tony Williams, who once told me a great Max Roach story. I was asking Tony about the K Zildjian that he used on Miles Davis’s Four And More album. Tony took me out to his garage and showed me the legendary cymbal. “Max Roach gave me this cymbal,” Tony explained, “and he said, ‘If you’re gonna hit this cymbal, HIT THIS CYMBAL!’” That cymbal had been played so much by Tony that it looked like a Slinky or a big spring that had sprung.

David Garibaldi

Tower Of Power

Max was before my time, but I was certainly aware of him, and have listened to, as well as own, some of his recordings. For me, the thing about him that stands out the most, and is so very inspiring, is his individuality. Isn’t this what we all strive for? Thank you, Mr. Roach.

Advertisement

Richie Morales

Spyro Gyra, Dave Samuels, Gato Barbieri

Innovation: The act of innovating or effecting a change in the established order; introduction of something new.

Max Roach’s passing has caused the music world in general and the jazz world in particular to take pause and reconsider the magnitude and depth of his musical contribution. His style was considered radical at first, as is all artistic innovation. His highly refined technique honed in long, after-hours jam sessions enabled him to play at blistering tempos, which elevated the drumset to front-line status in terms of jazz instrumentation, making him a pioneer in the creation of the musical styles that came to be known as bebop and hard bop.

As a bandleader, Max Roach used polyrhythms and odd time signatures in his arrangements of jazz standards and original compositions predating the 1959 commercial and innovative success of great jazz composer Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five,” featuring another drum titan, Joe Morello. Check out the recordings Clifford Brown And Max Roach, from 1955, and Jazz In 3/4 Time, from 1957.

As a social activist in the early 1960s, Max Roach was at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement. composing the “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite” on commission from the NAACP, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. This piece was banned by the then-apartheid state of South Africa. During the violent decade of the ’60s, such social activism was courageous in view of the inherent danger present both commercially and physically for a black jazz artist or any public figure advocating social change. Advertisement

Max Roach’s soloing was highly organized and compositional. He was a master of theme and variation, using motific and sequential ideas and dynamics, never displaying technique for its own sake. He was a master in the use of brushes. Max was always a “melodic” drummer. Later in his career, as his set grew larger, he used his toms to even more melodic effect. going so far as to incorporate a tympani pedal on his floor tom to create more tonal motifs in his soloing.

For those readers that might feel, “Well, jazz isn’t really my thing…” consider that many of the first-generation heavy rock drummers of the ’60s as well as some later-generation progressive rock players are indebted to Max Roach. Some of my favorites:

Ginger Baker: “Toad” a solo full of Max quotes, African polyrhythmic and bebop ideas, and of course ’60s excess.

Mitch Mitchell: Probably coming a little more out of Philly Joe Jones and Buddy Rich stylistically, but Max is in there.

John Bonham: Yes, Max was playing Bonzo’s kick drum and tom ideas back in the ’40s, albeit in a different context.

Advertisement

Cora C. Dunham

Prince

Max Roach’s life is definitely a reflection of the science of drumming–that is, the concept of several elements proficiently being engaged at one time.

Max has been an inspiration not solely because of the We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, his honorary degrees, or even the park in London named after him, but because of the risks he took in the musical movements throughout his life and the waves he made in the political, racial, and social arena in the ’50s, ’60s, and beyond. He was far more than a drummer. His writing and experience graced the world of jazz, theater, hip-hop, ballet, and film, and was notably revolutionary.

Initially the role of drumming in the swing era and big band era was tucked into the ensemble sound as support. Max brought drumming to a creative dimension as a solo instrument. His approach as a drummer respected the other players and the arrangements because of his sense of tonality, time, and rhythm.

I had the pleasure of witnessing an intimate solo performance at the Armour J. Blackburn University Center during my senior year at Howard, and thanks to my private teacher, Grady Tate, I spoke with him and sort of marveled at the friendship of these two incredible people at a time when I was evolving and cultivating my path as a musician. So I honor Max Roach for his sensitivity to the world, his standards of creativity, and the impact he made on so many musicians. I hope that other drummers will strive to use their influence in the music community as a light and a voice

for making a difference, just like Max did.

Advertisement

Ulysses Owens Jr.

Mulgrew Miller

Upon graduating from Juilliard’s jazz program, my instructor Billy Drummond suggested that for my senior recital I transcribe a Max Roach solo drum piece from the Drums Unlimited album. Step by step, I orally transcribed “The Drums Also Waltzes,” and then studied the written transcription I acquired from John Riley. I learned so much about rhythm, melody, composition, and, most importantly, phrasing.

Studying something that came from the blueprint of Max’s mind and ability was an honor. I felt he indirectly passed on something precious to my generation, and that is the gift of who he was and will always be to music, and to the drum community at large.

I moved to NYC in 2001, and I was unable to see Max play. But I felt that, through studying his records and watching footage of him, I still have ample opportunity to understand what it took to be one of the greatest drummers that ever graced this planet. Advertisement

John Blackwell

Prince, Justin Timberlake

There is so much that can be said about the man who I had the honor of meeting one day at Berklee College Of Music. Max helped me in so many ways–learning how to swing , learning how to improve, learning the hi-hat sweep…. I will miss him dearly, and so will every drummer in the world. He paved the way for us all. God bless you, Max, rest peacefully in God’s precious arms, and give my daughter Jia some drum lessons up there in heaven, okay? [smile] God bless.

See the December 2007 issue of Modern Drummer for the complete article on Max Roach.

Top photo courtesy Gretsch Drum Company, bottom photo by Paul La Raia.