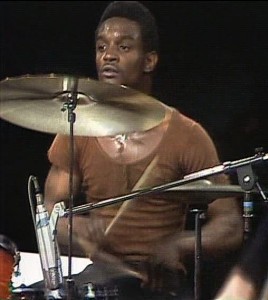

Alvin Taylor

Classic Tracks With George Harrison, Elton John, and Beyond

by Billy Amendola

We continue our conversation with the drummer, who’s featured in the April 2014 issue of Modern Drummer magazine, on sale now.

MD: Do you remember the gear you used on George Harrison’s Thirty-Three & 1/3 album?

Alvin: Coming over from America to [Harrison’s home/recording studio] Friar Park, I used the kit that was there. Jim Keltner had donated a drumset to George’s studio. There were Zildjian cymbals and a Rogers Dynasonic snare drum—which sounded great—along with two suspended toms and a floor tom.

MD: How did you track the drums?

Alvin: The tracks were recorded pretty normally. We never used any click track; everything was human-feeling. I would count off the songs and we would just play together as a rhythm section—me, George, and Billy Preston, David Foster, or Richard Tee on keyboards, with Willie Weeks on the bass. All the basic tracks were recorded together. There were some overdubs done in the end, where George did some slide and rhythm guitars. I never overdubbed drums. What you hear me playing was exactly what I played live to tape, though there were some percussion overdubs by Emil Richards, such as tambourines, woodblocks—all the little goodies that go along with sweetening up a track.

MD: What are some of your memories of playing with Little Richard?

Alvin: Playing with Little Richard was one of the greatest thrills of my life. I’ll never forget being a busboy at the Biltmore Hotel in Palm Springs, California, and the owner allowing me to play with the band called the Soul Patrol. They were playing in the lounge there. The drummer would get totally inebriated and couldn’t perform. The guys in the band found out that I could play drums and gave me an audition on a Saturday. They told me they would like me to sit in and play with them in case their drummer was ever unable to make it. Well, one night the drummer got drunk and he was out, and I was in. Advertisement

So I got on the drums and played, and in walked Frank Sinatra, Little Richard, Sammy Davis Jr., and Billy Preston. I knew who Sammy Davis Jr. and Frank Sinatra were; I had no idea who Billy Preston and Little Richard were. But Little Richard was very excited, and he came in the dining area where I was unloading dishes. He was screaming and yelling, and saying, “Oh, my God, I never heard a drummer like you since I left Macon, Georgia. Honey, when I heard you play, it made me scream like a white lady!” He asked me right on the spot if I would be his drummer. I was kind of dumbfounded. I was only thirteen years old at the time, and had no idea who he was.

I grew up on an Indian reservation in Palm Springs, and there were a lot of Indians there. The Indians are very particular in the way they dress, especially for their rituals. And Little Richard had this bandana on and all of these feathers coming out of his hair, and he reminded me of an Indian chief. I gave him my phone number and he talked to my mom, asking her if I could be in his band. My mom’s reply: “Absolutely not!” Richard, not wanting to be outdone, had his manager, Bumps Blackwell, call my mom and address the issues that concerned her. My mom’s reply was that I wasn’t doing well in school and that I needed the nurturing and the education that was important for me in order to be able to live a good life. So Bumps Blackwell addressed those issues by assuring my mom that I would have a tutor and my own bodyguard, and that I wouldn’t be on the bus with the rest of the band but would rather fly first-class with Richard.

We opened up a show for Elvis Presley in Las Vegas at the International Hotel. Our guitarist was Jimmy James, later known as Jimi Hendrix. Billy Preston played the organ, Richard played piano, and there was an eighteen-piece orchestra. I’ve got to tell you, that was some experience for a fourteen-year-old. Advertisement

Richard took good care of me. He was like a big brother or kind of a father figure to me. He treated me with love and respect at all times. Richard was notorious for firing drummers because they couldn’t keep good time. Let me share a secret with you: The easiest way to make sure that you’re playing in time with Little Richard is to follow his left shoulder. If you listen carefully while you’re on stage with him, you’d hear his assuring words telling you, “Watch my shoulder.”

MD: You also worked with Bob Welch, who had a big hit with “Sentimental Lady,” which he’d recorded while he was the guitarist in Fleetwood Mac in the early ’70s.

Alvin: I was working with the Eric Burdon Band, and John Carter, who was an executive producer and the head of the A&R department for Capitol Records at the time, would come out to whatever city we were playing to see us. Carter would sit behind the drums and watch me, and he would always tell me, “I hope that we have an opportunity to work together someday.”

When the Eric Burdon Band broke up, Carter called me to his office to tell me that he was going to do produce a solo album for Bob Welch, who had just left Fleetwood Mac. He wanted me to be Bob’s music director and put his band together. I asked him to give me some tapes so that I could figure out what type of musicians I should look for. I went home and listened to the tape, thinking, This is pretty good. I don’t understand why he doesn’t want to use the guys on the tape. Advertisement

So a couple of days later I got back with Carter and asked, “Who’s the bass player”? “Oh, that’s Bob.” “What about the guitar player”? “Oh, that’s Bob too.” “The keyboard player”? “Bob.” “What about the background singers”? “Bob too.” I said, “For crying out loud, we already have the band, at least for recording purposes.” “What do you mean”? “It’ll just be me and Bob.”

He looked at me like I was crazy. “How are you and Bob going to do this”? I told Carter that the best way for us to do the project was for me to play drums and Bob play the instrument of his choice for the basic tracks. Then he could overdub the other instruments and vocals. When we got to the point where the tracks were starting to shape up and sound really good, I told Carter that the only other thing we needed were some strings. I gave him the number of my good friend Gene Page, who I had done a lot of work with for Motown and other artists. He was an awesome arranger and extremely good at writing string parts, so Carter hired him, and that’s how we recorded the French Kiss album and the two albums that followed it.

MD: How did you come to work with Elton John?

Alvin: A very good friend of mine, producer extraordinaire Richard Perry, asked me to do him a favor and go out on the road to help promote Leo Sayer’s “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” single. At the time I was one of the first-call drummers in town, and I didn’t want to leave town, because I found out that once other producers find out that you’re on the road and not available for in-town sessions, they start calling other drummers. So I was afraid to go on the road, but Richard offered me plenty of other work, and there wasn’t a drummer in town who didn’t want to work with Richard. He was the busiest producer in town and had his own recording studio, and he was always busy with projects. And he offered an attractive substantial earnings to tour with Leo. So I consented.

Advertisement

Alvin: A very good friend of mine, producer extraordinaire Richard Perry, asked me to do him a favor and go out on the road to help promote Leo Sayer’s “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” single. At the time I was one of the first-call drummers in town, and I didn’t want to leave town, because I found out that once other producers find out that you’re on the road and not available for in-town sessions, they start calling other drummers. So I was afraid to go on the road, but Richard offered me plenty of other work, and there wasn’t a drummer in town who didn’t want to work with Richard. He was the busiest producer in town and had his own recording studio, and he was always busy with projects. And he offered an attractive substantial earnings to tour with Leo. So I consented.

Advertisement

One night the producer of the band that was opening up for us came backstage. I can’t recall the name of the band, but I do remember the producer introducing himself as Clive Franks and saying, “I’m an engineer and a producer, and my next project is Elton John.” He said that he would like to have our bass player, Reggie McBride, and me work with him on that project. So after the tour with Leo, Reggie and I took a flight to France to record Elton’s 21 at 33 album, featuring the hit single “Little Jeannie.” Things went so well with that album, we were called back for a second one, The Fox.

It was wonderful working with Elton. He was very humorous and fun to work with. He was a great boss and very easygoing. Whenever I asked him what he wanted me to play on any given song, his reply was always, “Do whatever you feel.” So I wrote and played all of my own parts for Elton. No charts, no click tracks. Just that good-old toe-tapping, finger-popping music.

MD: You mentioned playing with Eric Burdon before joining Bob Welch. You also worked with Stevie Wonder. What was it like working with each of them?

Alvin: Working with Eric was a bit difficult. It had nothing to do with him; it was his producer and manager that made it difficult for the band to work together. Eric was a very creative gentleman. He pretty much knows exactly what he wants. But since he’s not a trained musician, he has a strange way of getting his ideas across to his musicians. I learned to be sensitive to what he was saying, which enabled me to grasp the bigger idea. Advertisement

Eric reminds me of a very artistic movie director. His biggest thing was that the music would be married to the movie ideas he had in his head. There was always a great story behind his songs. I remember once he said, “There’s no greater marriage than music and videos.” Five years later, MTV came on the scene. Wow, there was a self-fulfilled prophecy glaring right at me—music and videos together! When from the voice of a genius named Eric Burdon, it had already been prophesized. Eric was a great boss to work with—and a very talented artist.

Stevie Wonder is a real genius, to say the least. He has such a keen sense of awareness of what’s going on. It’s always exciting working with him. He is very particular about the way the drums are tuned and the sound of each individual drum. I absolutely loved working with Stevie.

MD: Tell us your experience on playing the very first Saturday Night Live show to air.

Alvin: I was with Billy Preston. George Carlin was the host, and Janis Ian was a guest. We had bassist Bobby Watson and guitarist Tony Maiden from Rufus, along with guitarist Steve Beckmeier and keyboard player Truman Thomas. Paul Shaffer was the bandleader. At the time he was using horn players from Tower of Power. We also had background singer Venetta Fields. It was an awesome group. We had a great time during this historical event. Advertisement

MD: How did that gig come about?

Alvin: Diana Ross’s first husband, Robert Ellis Silberstein [aka Bob Ellis], was Billy Preston’s and Rufus’s manager. He arranged for us to all get together.

MD: How have you seen the music business change since you started?

Alvin: I’ve seen the music business change drastically over the years. Many of the changes are groundbreaking, some are tragic, and some positive and uplifting.

In 1964, the Beatles arrived in America. When their plane touched down at JFK, there was a crowd of about 3,000 people waiting to embrace and welcome them to our country. The volume of records that the Fab Four sold here was unprecedented. This sealed their artistic and financial freedom forever, allowing them the opportunity to go in the studio and craft albums like Revolver and Sgt Pepper. This expanded the parameters of modern music and paved the way for others to do likewise.

Then festivals came on the scene—Monterey Pop Festival, Woodstock, Devonshire Downs, California Jam—not to mention the Haight-Ashbury love-in days in San Francisco, where we had artists like Otis Redding, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Grace Slick and the Jefferson Airplane…. There was also Motown, Stax Records, and the Sounds of Philadelphia, then Donna Summer, the Village People, and the Backstreet Boys. Those were the eras that set the template for large-scale music-business profits.

In 1981, MTV was launched. This revolutionized the way that music was packaged and sold. The perception of television visuals changed the music industry forever. I recall taking my own drumset to the studio and setting it up myself, and dragging the drums from club to club, having to set them up and break them down. It went from that to having my own choice of cartage companies that would maintain my drums and keep them in storage, then bring them to wherever I needed them, set them up, break them down, and take them back to storage, until the next time I needed them. Advertisement

Gear-wise, I started out with just my drums and ended up with triggers on them and programming electronics. I’ve never been the greatest programmer, but there was a time that playing live drums was dead, and the only thing producers wanted were programmed drums. One producer told me that the reason he liked programming parts was, “The drummer is always on time, you can tell him what to do, he’ll never talk back, and you don’t have to pay him.”

Then, in 2001, Apple introduced iTunes. Behind the podium at Macworld in Silicon Valley, Steve Jobs ushered in the digital age of music. This literally changed the way that people interact with music. There has been a seismic shift away from vinyl and CDs to MP3s, and from albums to singles. Quite a bit has changed. There were many, many record labels once, but it’s boiled down to what we call the big four: EMI, Sony/BMG, Warner Music Group, and Universal Music Group. A lot of the record labels have gotten lost in the shuffle, because everything has gone digital. I’m just happy to be alive to see all the transitions.

Click here to see the table of contents and/or to order the April 2014 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.