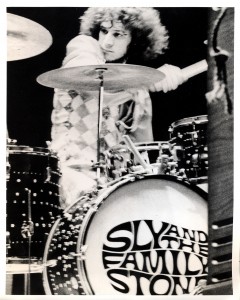

Greg Errico on Sly and the Family Stone’s Fantastic, Forgotten Concert Document <em>Live at the Fillmore East</em>

by Robin Tolleson

Listening to the recently released Sly and the Family Stone set, Live at the Fillmore East (Epic/Legacy), the band’s original drummer, Greg Errico, admits to getting quite excited, “almost like a fan,” partly because he’s long wondered what became of the recordings. “They disappeared for years,” he says. “I had copies in boxes stored away, and then it started showing up on bootlegs. It was 1968 when we did that—for some reason it just never came to be.”

Live at the Fillmore East delivers four joyous, raucous sets, with all the imperfections and spontaneity of a live show—this particular one including previously unheard musical segues and between-song sermons, bizarre a cappella renditions of “Old McDonald” and “Hail to the Chief,” band beat-boxing, tight horns, drum solos, and the dynamic interplay of Errico and bassist Larry Graham. “I know Larry’s vocal mic wasn’t working, and there was feedback,” Errico says. “As a matter of fact, through a lot of the set there were problems. But we always thought back then that the band was at the top of its game. I distinctly remember the show. I can remember everything that happened.

“The moments that everything comes together, when the plane lifts off the ground and just takes flight…you get chills. Those were special nights.”

Recorded after the release of the band’s Life album, these sets contain Sly favorites like “Dance to the Music” and “I Want to Take You Higher,” as well as lesser-known but equally compelling jams like “Love City,” “Color Me True,” and “Chicken.” Advertisement

Says Errico, “We recorded songs, and that was one set of chops. And I can remember we found, how would you call it, mind muscles to the way you approach performing a song. Playing live, some tunes you did verbatim as you recorded it, and some tunes didn’t work like that. You had to pull it apart and put it back together, keeping the integrity of the song on the record, but making it work live. On a lot of those the band goes into overdrive and takes it to another place. And when we went from playing small venues to theaters or big arenas, you’ve got to change it up again. We had the unique ability to do that—that’s why it was an exciting live band.”

Says Errico, “We recorded songs, and that was one set of chops. And I can remember we found, how would you call it, mind muscles to the way you approach performing a song. Playing live, some tunes you did verbatim as you recorded it, and some tunes didn’t work like that. You had to pull it apart and put it back together, keeping the integrity of the song on the record, but making it work live. On a lot of those the band goes into overdrive and takes it to another place. And when we went from playing small venues to theaters or big arenas, you’ve got to change it up again. We had the unique ability to do that—that’s why it was an exciting live band.”

Sly kept the band on its toes, according to Errico. “We would have an arrangement, but we always had to keep an eye on Sly—he would change things up so that arrangement would go out the window. Everybody knew how everything was supposed to be, but anything could happen. That was one thing that attracted people like Miles to the band. Sly was a great arranger. He knew his music. We only had two horns, but sometimes it would sound like a big section because of the unique way he approached voicing them. It had a sound of its own. For Miles, a jazz player, the way we approached performing had a lot of that spirit.”

Errico drives breaks on several tunes with strong double-time beats and outstanding kick work. The drummer jokes that he would lose five pounds every night. “When we started the group I was seventeen and a half, the youngest one. I started playing when I was fourteen, and I’m self-taught. So it was just all energy. I didn’t have a lot of technique to fall back on. It was all by the seat of my pants. Later I started figuring out why I was doing what I was doing, what it was called, and where it came from.” Advertisement

While his drummer friends were studying method books in high school, Errico was playing along with records. “I’d come home and go downstairs in the rumpus room. I had my drums there and a 45 rpm record changer, and I’d put on everything from Xavier Cugat to Buddy Rich. I’d practice to ‘Take Five’ to some Otis Redding and James Brown, and just play. I love all kinds of music. San Francisco was a great place to grow up; it’s an international intersection so you had music from all over the world on the radio and all around you.”

Errico credits his musical bond with legendary bassist Larry Graham to “natural chemistry.” “We used to hang out, go to shows, go places together,” he remembers. “The relationship was developed by playing. We would take the spirit of something that we heard and dug, and project the spirit or the energy of it, the concept, into something. We had an understanding of how important it was for the bass drum and the bass to be together, but also how important it was for them to avoid each other in certain places, playing counterparts. We just have a natural understanding.”

Advertisement