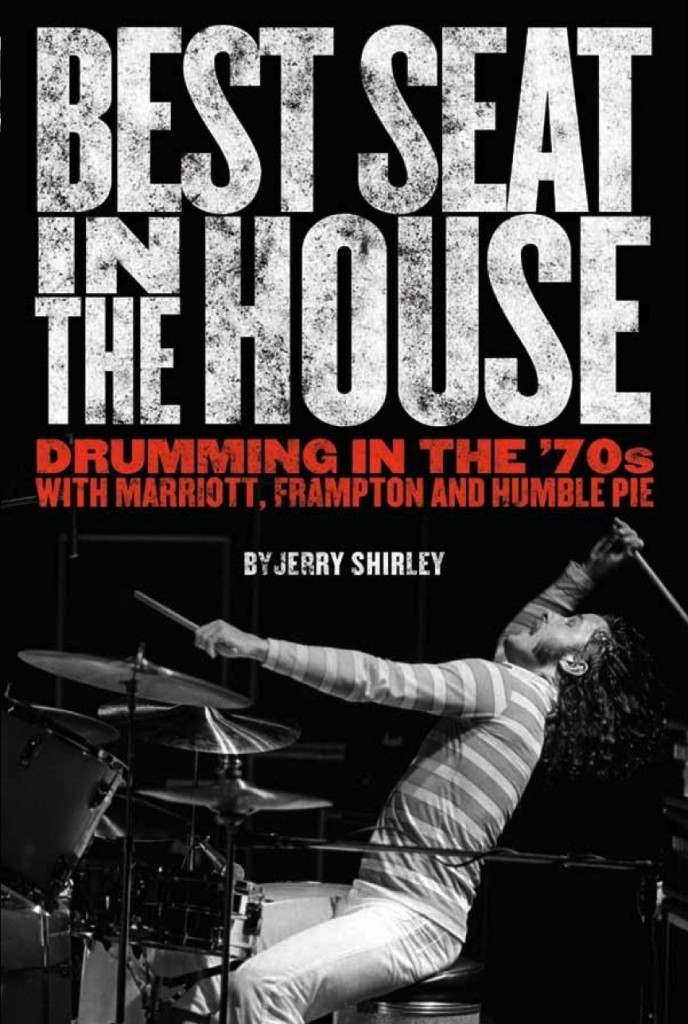

Jerry Shirley

The September issue of MD features an Update with the great Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley, who’s just released his book Best Seat in the House: Drumming in the ’70s With Marriott, Frampton and Humble Pie. In chapter two, “Ready Steady Go! November 1961 to December 1966,” Shirley describes his foray into playing pubs at eleven years old, discovering rock ’n’ roll, and dodging jelly babies at a very “fab” Christmas show.

My “Bitzar” drum kit (bitsa this, bitsa that) consisted of a Gigstar bass drum, a Broadway snare drum (which may also have been made by Gigstar), an Olympic hanging tom, a strange pair of bongos that attached to the bass drum, a pair of hi-hat cymbals, and a ride cymbal. The Olympic hanging tom was an add-on that I got about a year after the original kit, and a floor tom came later, too. We set the kit up in the public bar so that Dad could recruit various musicians, who would have anything-goes music nights every Friday. The “band” would usually consist of a pianist and a drummer, who would make use of my kit. On the really happening nights, Dad would hire an actual entire band, which would bring their equipment. These were the nights I loved the most because it meant I could watch a drummer who invariably had a kit far superior to mine.

I would practice when I got home from school, and sometimes get to play along with one of the pianists, before the pub opened its doors. It was at about this time that I discovered rock ’n’ roll music. My brother Angus and I had become huge fans of Buddy Holly just before he died, which was not long before I got my drum kit. Also around this time, a certain local boy came to everybody’s attention. His real name was Harry Webb, and his band was originally called the Drifters, but he had changed his name to Cliff Richard, and his band had become the Shadows because they had to: There was already an American vocal group called the Drifters. The Shadows is a much cooler name anyway, as is Cliff Richard. Advertisement

The first duo [I took notice of] was Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Rock ’n’ roll it wasn’t, but swing it did. I soon became a walking encyclopedia of all things Fred and Ginger. The fact that Fred played drums like a pro came as no surprise; after all, tap dancing and drumming are cut from the same cloth, rhythmically speaking. But as natural as it was for Fred Astaire to be a good drummer, that doesn’t mean that a drummer—yours truly, for instance—will be a natural dancer. Far from it, I’m afraid: I couldn’t dance my way out of a paper bag. Still, I certainly became a huge fan of anything to do with the Swing era of my father’s youth, right the way through to Count Basie and Ray Charles. To this day, my personal musical ethos is, “If it don’t swing, it don’t mean a thing,” simply because swing can be applied to just about any rhythm pattern; it’s the human element in a rhythm section.

Speaking of swing, the other duo I saw on television back then were the two greatest American drummers ever: Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. One night, some show on the telly featured one of the now-famous drum battles between the two masters. It came on out of the blue, and when my father yelled at the top of his voice, “Come here quick!” I ran to see what all the fuss was about. I was mesmerized. I have to say that I’m not a fan of big, flashy, drum-solo-type drummers, but this was different. First of all, Krupa and Rich swung like a big pair of tits, plus they used syncopation as if they had invented it—and for me, at this early stage in my musical education, they may as well have.

The year spent living in the pub had both pros and cons to it. On the plus side, there was my discovery of drums, Fred and Ginger, Krupa and Rich, rock ’n’ roll, dancing girls, blues, and big band swing. As if that lot wasn’t enough to keep me occupied, there was my introduction to the musical genius of Ray Charles and Peggy Lee, both of whom came to me by way of my mother. Back then, for your parents to steer you in the right direction, musically speaking, was a real bonus, and I consider myself incredibly lucky in that regard. It was a fantastic kick-start in the right direction, which was summed up years later by none other than (this is where the name dropping officially starts, folks) Sir Paul McCartney, while I nervously interviewed him for a radio station I was working for (98.5 WNCX, “Cleveland’s Classic Rock”). He was talking about his discovery of Ray Charles through the records being brought into Liverpool from the USA by merchant seamen. As he told me this, I said, in a matter-of-fact way, “Yeah, my Mum turned me on to him when I was about nine years old,” to which he replied, with wide-eyed surprise, “Boy, you were really lucky!” Not that I needed reminding how lucky I was to have a mother with such impeccable taste, but to be reminded of it by a fellow musician who embarked on his voyage of musical discovery a few years before I did, and whose name was Sir Paul McCartney, was fan-f***in-tastic! Mum also had a tremendous outlook about music in general, and was typically non-judgmental. When asked what type of music she liked, she would reply, “I like any type of music, so long as it’s good” or “All types of music, so long as it’s well played.” Advertisement

In school, I dedicated the next two years to studying for the dreaded 13+, with improving my drumming skills a close second. Practicing drum rudiments was never my strong suit, but I was able to keep my hand in by doing gigs locally with the band Angus and I had put together. Our band was a legend in our own lunch break, rehearsing in our living room, dressed in our band uniform of sleeveless black suedette V-neck pullover vest, white shirt, blue tie, and black trousers. This snappily dressed little outfit comprised Peter Smith (a.k.a. Wag) on lead vocals, Angus on guitar, Martin something-or-other on bass, and me on drums. We went through several names, none of which stuck for more than a couple of weeks. In fact, I don’t remember ever doing a gig as a member of the Cementones (for solid rock, get it? Hey, it was Dad’s idea!); the Other Name Band, featuring Sue Denim (my idea); or Dick Hampton and the Weapons (Angus’s gem). The old man, through his chain of old friends in the local business community, had secured a gig for us—a charity show for a local disabled children’s home—which was announced in a feature article in the big local newspaper. Dad was tailor made for the role of manager/agent/publicist, as he was a natural salesman. He also had a range of friends and associates from having been a Freemason all his adult life and a Grand Master of at least two Masonic lodges.

During the spring and summer of 1965, two bands appeared on Ready Steady Go!—the best show ever broadcast on British television—that forever changed my life. The first were the Who, performing “I Can’t Explain,” pound for pound the greatest debut single ever by a British rock band. Then, not to be outdone, Small Faces performed “Whatcha Gonna Do About It” that summer. (Although, it has to be said, it was the Kinks, with “You Really Got Me” in 1964, who really got it all going on, and apparently inspired Pete Townshend to write “I Can’t Explain.”)

There have been a number of books and various album liner notes that tell the story about how my brother and I were complete Small Faces freaks, and that our band did nothing but try to copy Small Faces. Whilst it was true that we did that to a certain extent, we were also a Who copy band—and in that period between the early spring of 1965 and the end of 1966, just about every band in England was doing the same. That’s how much influence those two bands had on everybody. Advertisement

A lot has been made of the fact that our band’s name was Little People, which seemed a pretty blatant rip of Small Faces—but we had changed our name to Little People a full two months before we first saw Small Faces on RSG. The thing that struck us, and me in particular, was the incredible likeness among Kenney Jones, Keith Moon, and I. With Kenney and I, it was like looking in the mirror; it was freaky. Bearing in mind that we were all still kids, you can just imagine how it bowled us over to see Small Faces, a band of really cool-looking midgets who played great, sounded huge, and were on TV. They showed us that almost anything’s possible and that we did have a chance, so long as we played our cards right.

There were other similarities as well, although if you tried to guess who influenced whom, you might be surprised when you learned the truth. For example, I had just bought a new Ludwig Silver Sparkle Super Classic drum kit, so when I first saw Kenney on RSG shortly thereafter and noticed he was using the exact same kit, all I could say was, “Far out, man,” in the vernacular of the time. It had actually been Keith Moon who influenced me to get the silver kit, as he had one when I saw the Who on RSG. That’s probably why Kenney had one, too. Kenney loved Keith’s playing at the time, which is understandable: Keith was on fire back then. You could go to see the Who and not take your eyes off Keith the whole night—he was that good. Townshend was the same; you couldn’t take your eyes off him either. Thank God that, in those days, bands played two, sometimes three or four, sets in one night, so you got a chance to focus on Keith and Pete, one set at a time.

By now we were living in Broxbourne, in a house near the river. The house was perfectly situated for a couple of young rock musicians, largely due to its close proximity to several great local venues. We were literally surrounded by great live rock ’n’ roll: The list of performers we saw or supported at one or more of these venues, mostly in 1965 and ’66, and often multiple times, reads like a Who’s Who of British popular music of the time: the Who, Small Faces, Spencer Davis Group, Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, Animals, Them (featuring Van Morrison), Moody Blues, Merseybeats, Fruit Eating Bears, Nashville Teens, Pretty Things, Creation, Mirage, Birds, Kinks, Action, John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, Cream, Geno Washington & the Ram Jam Band, Screaming Lord Sutch, Steampacket (whose ranks included Long John Baldry, Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll, and Brian Auger), Shotgun Express (Beryl Marsden, Rod Stewart, Peter Green, and Mick Fleetwood, among others), Undertakers (featuring Jackie Lomax), Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, Gary Farr and the T-Bones, and several others lost to the vagaries of my memory. Advertisement

On top of that little lot, Angus and I also saw, just before and during this period, many other acts elsewhere in England, including the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Yardbirds (with Eric Clapton), Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, and Brian Poole & the Tremeloes. (Later, in ’67, we supported Pink Floyd, then still led by Syd Barrett, whose two classic, fractured solo albums I would eventually play on.) All this before my fifteenth birthday! Looking back, it’s enough to make your head spin, but you have to remember that going to see live bands was then the only form of affordable entertainment that existed for teenagers other than the cinema or football.

In December 1964, Angus and I were lucky enough to get our hands on two tickets for one of the famous Christmas shows that the Beatles put on each year at the Hammersmith Odeon. The bill was outstanding: You saw not only the Fabs, but also the Yardbirds with Eric Clapton, Elkie Brooks backed by Sounds Incorporated, Freddie and the Dreamers, and more. But Angus came to see and hear one thing only: Eric Clapton—and Clapton was sensational. I also had reasons other than the Fabs to want to see the show. Tony Newman, the drummer with Sounds Incorporated, was out of this world; he too was a show all by himself. Plus, the band was as tight as a duck’s bum, and Elkie Brooks sang her ass off.

The show just kept getting better and better, and the Beatles hadn’t even played yet. But they had appeared in short theatrical comedic skits a la Morecambe and Wise, which I thought was incredibly inventive for the time, but it sent the peeing jelly babies into distraction. Even Freddie and the Dreamers were entertaining, if you like that sort of thing. And then the Beatles played. By that stage, they could have gone on and whistled “Dixie,” and it wouldn’t have mattered; they were that big. And the audiences were, in general, too busy peeing themselves and chucking jelly babies every which way to mind what was coming off the stage at them. Advertisement

The atmosphere was electric. It’s often been said that you couldn’t hear the Beatles when they played live and, equally, that they could not hear themselves. Well, I don’t know about other gigs, but that night at Hammersmith they were steaming. John and George’s combined guitar sound was a great example of how rhythm guitars should be played. The bass sound was huge; Paul was playing lovely pedal bass through a lot of the tunes, which suited them perfectly. Ringo swung from the hip. And the vocals were outstanding. Not bad for a bunch of lads who couldn’t hear themselves! It was a wonderful time to be a young man in pursuit of his dreams.

For more with Jerry Shirley, read the September issue of Modern Drummer magazine. To order his book, go here. And to join his Facebook book fan page, go here.