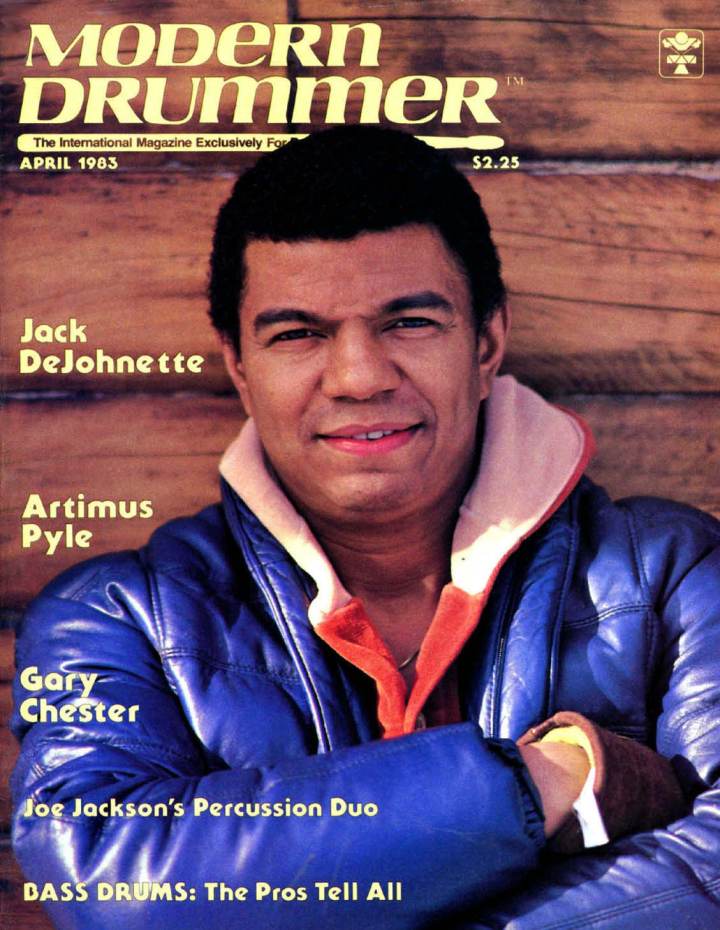

Gary Chester: Taking A Stand

Writing The History of Rock Drumming opened a Pandora’s Box. I knew it would. Researching the existing volumes of rock history made it clear that there was a shameful lack of recognition for the drummers’ contributions to this music. I had to begin writing with a clean slate that sometimes seemed like a freshly dug grave. The MD reader response was mostly favorable, but a few wrote in to correct some omissions and errors. I appreciate that. But, there were two oversights, in particular, that haunted me on one account and excited me on the other. That I left out Roger Hawkins haunted me. I don’t even have an excuse. Roger’s been an incredible genius of rock ’n’ roll drumming and continues to be. Anyway, I’ve phoned Roger and apologized and he was gracious enough to let me off the hook!

In early September I received a letter from Gary Chester, chastising me for “slighting” him and “the entire East Coast recording scene in the ’60s.” The letter went on to list a few of the hits Gary had played on. They included “Twist & Shout” by The Isley Brothers, “The Locomotion” by Little Eva, “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” by Jim Croce, “Rocky Mountain High” by John Denver, “Town Without Pity” by Gene Pitney, “Mr. Bass Man” by Johnny Cymbal, “Coin” Out of My Head” by Little Anthony & The Imperials, “He’s So Fine” by The Chiffons, “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head” by B. J. Thomas and “Downtown” by Petula Clark. Advertisement

In addition, Gary Chester recorded hits for Burt Bacharach, Jackie Wilson, Neil Sedaka, The Four Seasons, Dionne Warwick, Jay & The Americans, The Lovin’ Spoonful, The Archies, The Monkees, The Coasters, Simon & Garfunkel, Jose Feliciano, Dusty Springfield, Wilson Pickett, Bobby Vinton, Neil Dia mond, Frankie Lymon, Wayne Newton, Jan & Dean, and The Tokens, among others.

Among the writers at that time, Gary worked for Phil Spector, Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Cynthia Weil, Barry Mann, Teddy Randazzo, Howie Greenfield, Jeff Barry, Ellie Greenwich, Van McCoy, Barry Manilow and the team of Bacharach & David. All in all, Gary Chester has done about 14,000 dates. In other words, Gary is real good! That I left his name out of The History of Rock Drumming was because Gary’s always kept a low profile. Every body knows the hits he’s been on, but very few people know his name.

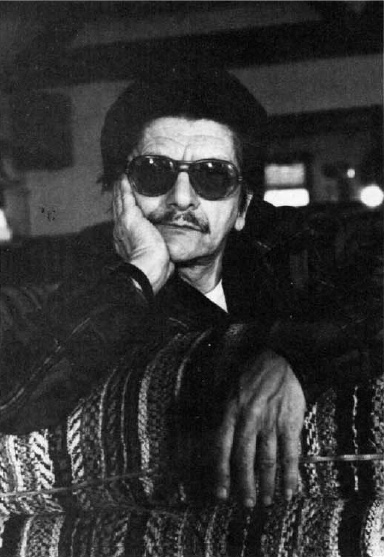

This interview was done at Gary’s home in upstate New York. He lives down a common dirt road in a serene setting. There are dogs running around the yard barking, a horse grazes in a fenced area in the back yard, and nearby are a couple of gardens that Gary loves. Max Weinberg says that Gary reminds him of Charles Bronson. He’s a short man with intense/sensitive eyes, half-hidden behind tinted glasses. What it is, is that Gary has a heart of gold, and to protect it, he’s developed a rough exterior. I learned to respect this man for his contribution to drumming, but more so as a human being. Gary Chester isn’t afraid to lake a stand and I respect that tremendously. Here then is an afternoon with Gary Chester. Advertisement

SF: We’re here to shed some light on your contribution to the New York rock ‘n’ roll scene. How did you get to do 14,000 sessions?

GC: Well, you know how the business is. First you do club dates, weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, opening delicatessans, stores…whatever! A fiddle player named Julie Held asked me if I’d ever done any record dates. I said, “Yeah, a few.” At that time I was doing maybe 50 a year with different jazz players. I had a couple of TV shows and I was working club dates and a couple of steady gigs in New York, but I was strictly a jazz player. Julie asked me, “Would you like to do a record date?” I said “Sure.” He said “Okay. Leiber and Stoller have a date.” And he told me the studio.

At the session, Bobby Rosengarden, Panama Francis and I were playing drums. At that time, Panama Francis was the king of rhythm & blues and probably the king of rock ‘n’ roll. He had to leave at five o’clock for another date. When he left, Mike Leiber and Jerry Stoller, who were the producers, asked me if I’d play drums. I said, “Yes. But, not like Panama. He’s the king.” Up until that point I’d hardly listened to rock. The date was La Verne Baker and the song was “Saved,” a gospel tune that became a hit. Next thing, I was recording with people like the Drifters and Ben E. King. Everybody wants a winner. That’s how I got to be in demand—in one year 165 leaders called me: Gary Sherman, Stan Applebaum, Phil Spector, Carole King, Bedford Hendrickson, Quincy Jones, Hugo Winterhalter, Don Costa, Barry Mann & Cynthia Weil, Donny Kirschner, just to name a few.

I became a recording drummer overnight. It’s scary to change that fast, especially coming out of the club date and jazz field. I was into another thing and I was making it, but I didn’t really know anything about it. Advertisement

I became the first white drummer to work with all the black artists in New York. First at Sceptor Records with Jerry Butler, The Shirelles, Dionne Warwick, Dee Dee Warwick, and Cissy Houston. Then Atlantic Records got hold of me and made me house drummer for them. Whatever black act came in, I’d play the date. Decca was thinking of going black, and I did a couple of dates with Louis Armstrong and Jackie Wilson. It all happened pretty fast, but that’s how I got into the record business.

It was a refreshing change from commercials. I’d been doing a lot of these for a jingle company run by Phil Davis. We worked maybe seven or ten hours a day doing commercials before I got into recording. It kept getting bigger and bigger. While I was getting more work, I was still playing club dates because of the insecurity of the whole thing. It hit me so fast that I was afraid it would evaporate if I stopped to take a breath. It’s tough to handle success; my ego started getting the best of me. I’d never turn down a gig. I started thinking I was the greatest.

I never listened to any other drummer. I had my own style and I didn’t want to mess with it. But I respected them all. The other hot drummers in those days were Buddy Saltzman—we did an awful lot of double dates—Jimmy Johnson, and Herbie Lovelle. Bernard Purdie came a little later. There was Al Rogers who’s now a Wall Street broker. He couldn’t hack it anymore. Then Billy LaVorgna moved in. He’s now contracting for Liza Minelli. The feeling in those days was friendship. If I couldn’t do a date I’d call Buddy. There was no jealousy. It was really a happy situation. Advertisement

SF: You didn’t have to worry that if you turned down a session, you might not get hired by that contractor again?

GC: That never happened. We were all always professional enough to never be late; to always be on the job and do the job the best we could. That’s the whole thing in this business. It’s not enough to play well. You’ve got to go in giving the man more than he’s paying you for. Since I was so busy, people started to ask me to contract the dates—that way they could be sure to get me. But I knew nothing about contracting. All I knew was how to play. But I learned.

SF: What does it mean to contract a record date?

GC: It means getting the players, renting the studio, getting the rentals. Pretty soon, I had my own rhythm section. It was like a family. All the musicians that I worked with in those days were very compatible. Being a contractor’s a funny thing. You start getting presents from people and it’s not even Christmas. Everybody wants to buy you. Then the engineers started to get in on it. They figured, “Gary’s hot. If he’s going to work with a new artist, he’s going to bring them to my studio.” It was like buying me. I resented that tremendously. I wouldn’t hire any contractors in my band—that felt too political to me. I was only interested in good players. Of course, if a guy was a contractor and also a good player, I hired him. But I never just hired a guy because he could turn around and give me a job. That stinks.

It got to the point where other leaders would bring artists from California to New York just to work with me. I got a call one day at home in Rockland County from Laura Nyro. I’d never heard of her then. She’s got a very sexy voice on the phone. She said, “Hello, is this Gary? My name is Laura Nyro. Did you ever hear of me?” I said, “No.” She said, “I’m calling from California. I want to block you out for two months. I want four sessions every day for two months.” I said, “Who’s your conductor?” She said, “Jimmy Haskell.” I told her, “Don’t get me wrong, but I don’t usually block out two months for anyone. I don’t care who the hell you are!” But she was sweet and I really respected Jimmy Haskell, so I told her to have him call me and that’s how we did the New York Tendaberry album. It was probably the biggest production I’ve ever done. It cost Columbia more money to produce this girl than Barbra Streisand. I contracted the whole date. I did it the way she wanted—expensive. I didn’t know what she was going to call for, so I had musicians stashed at Columbia Studios on 52nd Street on each floor, on the payroll, on the contract. I had a full string section on the third floor, horn players on the second floor and I had the rhythm section in recording. We did about a month and a half of that to complete the album. It’s very unusual and wasteful, I think. But Columbia had given her carte blanche. Advertisement

I loved working for Burt Bacharach. He really treated me great. We went to Vegas together and I was the highest-paid drummer, as far as I know, in the country. I went to Vegas without my wife and daughters. I missed them something terrible. When Vegas was over, the band was going to Tahoe. I said, “Burt, I’ve got to have my wife and family in Tahoe or I quit.” Burt said, “Don’t worry, I’ll send you home—pick up your family and I’ll meet you in Tahoe.” He paid for everything. The man was a gentleman.

I did everything Burt’s done. All the records, including B. J. Thomas and Dionne Warwick. Anything that Burt and Hal David touched, I was on. Anytime I did a date with Burt I felt like I’d eaten a fantastic meal. Everything was so perfect, emotionally and chord structurally. He rushed like a son-of-a-gun. When we were in Ta hoe and Vegas I used to conduct the band for him a little bit when he was talking to the audience. I’d give the whole band the tempo for the tune. He’d turn around and rush the time and the whole band would come in on my tempo. Burt would sit down and say, “Thanks, man.”

SF: I’ve heard that one reason why Burt wrote so many odd measures in his songs was because he couldn’t keep time.

GC: That’s not so at all. He wrote those odd times because it allows the lyrics to breathe. Take those times out of context and sing the lyrics. You’ll notice how Hal David’s lyrics just roll. There’s space for breath; space for consideration. Those are written in music. There’s a reason for everything he does. Burt used to call me at four o’clock in the morning. He’d say, “Gary, I wrote a tune. Tell me what you think.” I’d put the phone to my ear and he’d play the tune and say, “What do you hear?” Then we’d talk about it long dis tance for half the night. He’d bounce ideas off me and sometimes he’d incorporate my suggestions into his work. He was a great guy. I worked with him for 14 years. Then it was time to move on. When I decided I didn’t want to work for Burt anymore, I was crying when I told him. I said, “I can’t make you anymore. I can’t do this music.” He said, “Okay. I understand.” Advertisement

I was in the hospital one time with a slipped disc. I contracted about 25 dates from the bed! The nuns were contracting my dates for me. This was 1969. I had given up. I already had my wheelchair picked and the size pencils I was going to sell. I was finished. I hired a nurse, a masseuse and I just prayed. All of a sudden I get a call from Artie Butler. He said, “Gary, I got a date for you at RCA.” I said, “Hey Artie, I can’t play.” I’d lost every muscle in my right leg. When they put me in traction it just pulled the muscles out. You know those fat old ladies with the fat under their arms? That’s what my leg looked like. I was crying like a baby. Artie said, “Don’t worry about it. You can play percussion.” My wife drove me down and I walked into the studio on crutches. Another drummer was there. I sat in front of him playing tambourine, conga, bongos and shaker. When I play percussion on a date, I don’t consider myself a true percussionist—to me a percussion player is a highly trained musician who plays mallets, timpani, bells and even some sound effects, plus all Latin instruments and also reads treble and bass clef and can play some piano. So the word “percussion” really isn’t used the right way a lot of times. I couldn’t stand the drummer’s time; it was driving me up a wall. This was a date for The Archies, which was not really a group, just some studio musicians. The idea was conceived by Don Kirschner and produced by Jeff Barry. These same people also did The Monkees. Anyway, I finally said to the drummer, “Let me play the next one. If I can’t play—you cover me. I’ve got to find out if I can play anymore.” The first tune was “Sugar, Sugar.” Afterwards, I knew that I hadn’t lost that much, and that after 35 to 40 years, it was okay to take a 32-day break. But I still had to build all my muscles back up again. I enjoy playing because I make it creative and innovative—for instance, I started putting the tambourine on the sock cymbal, without a head, after LaVerne Baker broke it when she was using it on a date. That gave me a jinglely sound when I closed the hi-hat. I even played ashtray on a lot of tunes—one of the ashtrays with sand in the bottom of it. I found mine in a doctor’s office. If I wanted a light sound and the lows were rolled off it by an engineer, the ashtray would sound like a very controlled marraca. I wouldn’t use it if it sounded like an ashtray. The beads always roll in a marraca. In an ashtray, the beads only move when you hit it. But the ashtray needed balance—I said, “I’ve got the feminine part, now where’s the masculine?”

I went out and bought metal thimbles. I’d put them on my index fingers and I’d play on the center of the ashtray where all the pebbles were. Rather than let the peb bles roll, I made a direct contact between that little metal piece and the pebbles. I’d sit the ashtray on either a timpani or a snare drum and I’d get down into the sound chambers. It’s a great sound. I’ve even played cardboard box. Because of this, I’m probably classified as a “character” in the business. I feel drumming is great, but you’re not going to get anywhere if you’re going to try to show everybody how you can play. You’ve got to do something extra for each new project.

We were doing a date called “Heartbreak” for Burt Bacharach. We had this big orchestra, about 65 guys, with strings and everything. Burt said, “Gary, I want you to play the bass drum and simulate a heartbeat.” I played the drum and Phil Ramone, the engineer, asked, “What do you think, Gary?” I said, “I’ve got an idea.” I went out and bought $10 worth of big balloons. Everybody was blowing them up. I finally found one that was blown up big enough. Now picture this: Columbia Studios, 52nd St., Burt Bacharach. All the heaviest musicians, and here’s Gary Chester with a balloon and a timpani mallet. I said, “Okay. Record this.” Pounding on those ballons made the heartbeat sound they were looking for. Later on I overdubbed a light drum beat. But, can you imagine how crazy it looked? Advertisement

I was in the control rooms more than I was in the studio. If I didn’t like anything, I would mention it. A lot of times it was as if I was producing the date. Every date I did, I felt like part of. I did it because I took pride in what I did. Some of the guys resented me for being a perfectionist. I would kill a lot of time. I’d pinpoint the mistakes in the band. When you’re conducting a band, especially when you’ve written for it, you haven’t got time to hear a cello player make a mistake. You don’t hear everything.

I was the first drummer to use “cans,” or earphones, in the studio. The reason I did was because as a kid we had nobody to play with so we had to play with the radio. They had a jazz show and I used to sit in back of my father’s barber shop and play for eight or nine hours a day with these bands. When it was loud enough I felt like part of the band. The studios scared the hell out of me. In order to feel comfortable, to feel enclosed by the music, I insisted on wearing “cans.”

SF: No previous drummer ever wore headphones?

GC: Right. You didn’t have to worry about it because you only had one or two mic’s and nothing was that loud. When everybody had their own mic’—I got lost in the shuffle. I wanted to hear everything. I’d ask the engineer, “Can I have the whole mix, please?” I didn’t get only drums. I had to find out where I belonged in the arrangement. When I put “cans” on, I could hear what I was doing to the band. I could feel if I was pushing the band or hanging the band up or whatever. Advertisement

SF: When I was writing The History of Rock Drumming, it was a real challenge finding out certain songs that a specific studio drummer played on. In many instances two drummers would claim that they were the only drummer on a song. Is there often more than one drummer?

GC: What happens is that sometimes we’d record four or five rhythm instruments and everything would be fine. Then the artist would put overdubs on. It might change what’s needed in rhythm and they might call in somebody else. Let’s use Paul Simon as an example. Say we finish a track in New York—Simon would then take the track out to California to overdub himself, or maybe he heard something else that he wanted put on. When he listens to the track he thinks, “If only Gary would’ve cut that.” Something that wasn’t there at the time. So he says, “Well, let’s call Hal Blaine to cut it for us.” Hal Blaine would either do my track over, or he would overdub in just a certain spot on the record. I’ve done that a million times.

SF: Who gets credit on the record?

GC: There are no rules about who gets the credit. It’s up to the artist, the producer. It never bothered me if I got credit or not. I did my job and got paid for it and that was that. I remember producers coming over from Italy with a recording of the Milan Symphony. They took the singer off and put an American singer on it. Then they wanted to take the drummer off too. They told me, “I want you to be put on the track.” Now, the recording had no rhythm section; just strings and voice. It took me six hours because the time wasn’t there. Time is the whole essence of playing. If you’ve got the feeling, you can keep time on anything. I once got a call from Quincy Jones. He had a lawnmower in the studio and I had to keep time with the lawnmower while we were playing this date! I was known as the Human Metronome in the business. I studied time. Davey Tough, Nick Fatool and Morey Feld—these guys are not soloists, but their time is so gorgeous. I love time. Advertisement

SF: I know you lived with Dave Tough. Did you ever talk about time?

GC: We used to sit and play brushes all night.

SF: With a metronome?

GC: No. Just between ourselves on a cardboard box. What grooves we used to get! That’s the trouble with the younger geneation. They don’t know time as well as they should.

SF: Did you ever practice with a metronome?

GC: No. I work with a click track with all my students. I never had to play with a metronome because God gave me something inside. I have a born-in quarter note. When I went into records there was no click track. It was just the pulse of the room. I don’t think you can show me a record that’s acceptable, where it starts and ends in the same tempo. Just for fun, though, I can groove my butt off on a click track by playing around i t . I look at it as a great bass player. The trick is, don’t let it confine you. It’s no good for records. For commercials and movies it’s fantastic because you’ve got to worry about frames. Everything’s got to be right on the button.

If we finish a take and the guy says it timed out perfect, I don’t fool with it. But if he says, “We ran over,” I say, “Don’t touch it. Let me take care of it.” Say it’s a 60-second spot and we run 63 seconds. There are three ways of doing this. Either you play behind the beat, on the beat—which is what the arranger is counting on—or on top of the beat. I always play on top or behind the beat. I’ll play 1/32 above everything. If everybody plays that way for enough bars, we’re in.

SF: How did you develop the ability to play ahead of, on top of or behind the beat?

GC: First you’ve got to know where the beat is.

SF: Can that be learned?

GC: I think you could understand it. I don’t think anybody can really do anything unless they really understand it and make it part of their life and lifestyle. To me, everything is rhythm. I have my students playing four-way coordination that’s really scary. On top of that, they have to sing their quarter notes while playing all this. It’s very, very difficult. I’ve got them singing the top line, which is what they’re playing on the sock cymbal. Then they sing the bass drum line. Then they sing the line that they’re playing. The trouble with most drummers today—not the good ones, but the kids who are coming up—is that they look at drums as separate objects. They haven’t thrown themselves into the instrument. They don’t sing what they play, like Al Jarreau. I’m very much into Al Jarreau, George Benson and Erroll Garner. Advertisement

For some unknown reason, only the drummers who understand what they’re doing can sing a solo. Most drummers aren’t even brought to their solo by the band. They can’t wait for the drum solo. They’re so egotistical that they put their mother, the kitchen sink and the toilet in a one-bar solo! That’s not what music is all about. Once you really appreciate what time is and what a quarter note means to you, the whole thing takes on a different coloring. The band has to be more important to you than your solo. Even so, the drummer’s got to be inspired. After all, you’re all by yourself back there. A drummer gets in a room and that’s it, man. He’s stranded! The only way he can hear what’s going on is with “cans.” That’s the only communication he’s got with the leader and the engineer. So in order to be inspired you’ve got to learn how to listen.

SF: Have you spent a lot of time studying melodies?

GC: I sing. Scat singing. I enjoy playing an instrument and knowing where it’s going musically.

SF: It seems that one of the secrets of having good time and being a good listener is having a thorough knowledge of melody and lyrics.

GC: Yeah. Lyrics are awfully important. I remember when we backed Aretha Franklin. She was in the isolation booth and I was on the bandstand. The rhythm section was right in front of me. We were recording “Rockabye Your Baby (With a Dixie Melody)” and for some unknown reason, Aretha started to scat sing. I started playing along with her. It was crazy! She was such an inspiration that I was able to play the exact same scat she was singing. Then we both stopped. It was dead silent for a moment. It was the most sensational feeling in my life. I never knew her before that, but musically, we were married at that point.

Back in those days we’d usually play a fill to bring the singer in after she’d gotten through singing. There was a way of playing a fill. You don’t jump on a lyric. But, this one time Aretha sang off meter, and I went right along with her. It was a great feeling. Advertisement

If I work for you, you’re the king. My job is to make you look good. Today, a lot of musicians are playing for themselves. There’s no unity.

The good players, for some unknown reason, stay by themselves because they’re tired of the bullshit players. A lot of the kids today are party kids. Party, party, party. It’s not a party! It’s a business. The successful ones consider themselves very fortunate—and they should—because they’re earning money doing what they’, want to do. It’s a creative business but it’s also a disciplined business. Most drummers nowadays can do what they want, but can they do what you want? Many of them aren’t schooled and have no desire to learn. A lot of my students have trouble learning because they think they’re artists. Great artists. They’ll say, “I want you to teach me how to do your coordination, but I don’t want you to screw up my style.” I have to break the news to them: “Buster, you ain’t got a style! In fact, if you do, you don’t belong in the record business.” It takes a while before a drummer realizes he’s a drummer. Up until that point, he’s just kicking the hell out of the instrument. It takes years before he takes that set of drums and makes them a part of him. If you talk to a kid in high school, all you can talk to him about is the high school level. Talk to a kid in elementary school, and all you can do is talk to him on the elementary level. The trouble with a lot of musicians today is that they’re working out there and you’ve got to talk to them on the elementary level. Whatever happened to the high school, college and professional levels? Many have no idea of professionalism.

SF: How did you learn professionalism?

GC: You just learn it over years of experience. You start at the bottom of the business—club dates, weddings, Bar Mitzvahs. You have to have these to pay your dues. You also have to have demos to make records. You learn that nobody really gives a damn about you. You learn that nobody really gives a damn about how fast you play. It’s, “What can you do for me?” Once you start realizing that you’re just a cog in a wheel, then you’re learning professionalism.

SF: You spoke about having to learn to deal with success. I find that that’s as important to learn as is four-way coordination, for example.

GC: I do too. I want my students to feel inside like they’re the greatest drummer in the world. But I teach them to be humble on the outside. I do a lot of lecturing in my studio. Sometimes the kids don’t even play drums. I tell them what’s right and wrong in the business. I teach them attitudes. I spend time talking about publishing and management. I tell them about organizing a band and financing a band. How to deal with tough situations, like if the bass player gets pregnant and can’t do a date—that blows the whole band. But if you write charts or tunes, then you’ve got a book, you can get another bass player and you’ve still got a band. A lot of people don’t do that. It’s that party attitude. “Look Ma! I’m in a band.” It’s the same reason why some kids go to college—to get away from home and to have fun. But that’s ignoring the future. When he gets out of college, he’s a clone! Advertisement

SF: Like the multitude of Steve Gadd clones?

GC: Well, if you’re going to model yourself on somebody, Steve Gadd is a damn good choice. Steve is a mature innovator and he puts himself into whatever he’s playing. Steve is a very quiet guy. He’s very much withdrawn within himself; a heavy thinker. When you see him play, you know that this guy knows what’s good or bad. I saw a TV show where the interviewer was speaking to some of the greatest actors in the world. He asked one great actor, “Do you know how great you are?” The actor said, “I’m not great. I’m an actor!” The interviewer responded, “No. You’re great. Everybody worships you.” The actor said, “If I ever thought I was great, I would shoot myself. That would be the end of it.” In other words, you’ve got to believe that you can improve. To yourself, you’re not great. You’re only great to somebody who can use you to be greater for themselves. That’s the name of the game. Once you decide that you’re the greatest, you’re in trouble.

Steve Gadd got to be busy and it’s true, everybody started to try to sound like him. But they can’t sound like him because they’re not him. There are no two drummers in the world who play the same way. Everybody thinks differently. Everybody sees colors differently. Everybody sees problems differently. You’ve got to respect Steve for what he’s done and for the maturity in his playing. There’s only one other guy who thrills me as much when I hear him: Harvey Mason. That guy can really play. The business needs more people like Steve.

The next generation is going to have a lot of trouble because they don’t want another Steve Gadd. They’ll want somebody better than Steve Gadd. It was like that when I stopped recording. It’s typical for the business. First you’re hot, then you’re not! Like: “Get Gary Chester for every date” then: “Get Gary if he’s available. If not, get someone who plays like Gary,” and then finally, “Who’s Gary Chester?” If you’re lucky, this span can cover maybe twenty or so years, but your time is always eventually over. If you’re the greatest innovator, people will still copy from you and that’s just a fact of life. But it’s the truth—you’re only as good as what somebody can get out of you. “You make me money, man, you’re a giant.” That’s not how you judge yourself, but how the music business judges you. And believe me, it is a gigantic business. Advertisement

SF: Your wife touched on the difference between drummers who are “personalities” and studio drummers. Can you explain that?

GC: Here’s a perfect example: Buddy Rich, Billy Cobham, Alphonse Mouzon, Joe Morello, Jimmy Chapin, Roy Burns and Joe Cusatis are all fast they’re all tremendous—but none of them are studio players. Studio players are making a living in the studios and it’s a whole different world. You’ve got to be able to read flyshit, but reading isn’t enough. Sometimes you walk into a studio and all they hand you is a lead sheet. The word is not reading. It’s sensitivity. The drummers I just named are terrific performers, but they’re a different breed. They’re great soloists, very independent and are celebrities by choice. They are in the public’s eye and they enjoy it. I’ve always liked to be very low key. In the studios, I got my satisfaction from playing whatever was needed, making the producer happy and creating within the limitations of the requirements for the specific dates. I had a student I’d been teaching for seven years, gearing him for the studio. I teach studio technique and all the disadvantages of being in the studio. I have a four-track studio. I teach them what sounds they’re playing in the room and how it relates to mic’ placement. I overdub them on their own drum track to make sure they know if their time is screwed up. I found that this particular student didn’t want to bend. He wanted to play fast. He wanted to play speed. He cooked—but only fast. Slow? He couldn’t play. The hardest thing in the world is to play soft and slow. The easiest thing is to play fast and loud. Finally I said to him, “I’m going to have to drop you because you’re not doing me any good.” I’ve got to have someone out there representing me. That’s why I’m a serious teacher. I have no room for lemons. I won’t take kids who aren’t flexible enough to learn what I’ve got to teach. That doesn’t mean I’m only turning out session drummers. I just level with my students about where they’re headed.

I said to this kid, “You’re never going to be a studio player. You’re never going to make good money. But, you’re going to be happy. That’s all I’m concerned with.” I love the kid. I said, “You’re going to be a very happy drummer. But you’re not going to be able to read well. You’re not going to be able to play any kind of music. You’re a fusion player and that’s what’s going to happen.” So I started teaching him speed and related things. He’s the fastest drummer locally, and he’s building a reputation as a fusion player.

Every year I have a party for my students. The party we had the year before this we called an “emotional experience.” I had my students group into five drummers per group. There were four groups. They tell me an emotional feeling they have—it could almost be any kind of feeling, like hatred, love, the world sucks, whatever. Then, they have to write a piece on it for five drummers. I did that to try to get the drummers to realize that it’s not just a set of drums. I want to hear you cry on the instrument. I want to hear you resent. You should’ve heard what I got! Absolutely fantastic. It was really scary because out of 40 students I think I got to 20 of them. I want to be the greatest teacher in the world, and you don’t teach by playing for the students. You teach by talking and listening to the students. Advertisement

SF: How long have you been teaching?

GC: About six years. I couldn’t teach when I was busy all day and night in the studios, but the studio has taught me what not to do. Sometimes you get producers who actually come up and ask you, “Can you play this?” You look at him and say, “No, I can’t play that.” He says, “Well, you’re supposed to be able to play that, schmuck! You’re a drummer! I’m not even a drummer!” I say, “That’s why you can play that.” Then they’d want the impossible on the date. So I’d have to write it out first and say, “Alright, give me 10 minutes so I can practice it so we can cook. I can’t play anything that I don’t understand.” I’d get it, write it down and put it in my safe. I gathered a lot of this crap, man. You just can’t play it because it’s drumistically impossible. That’s what my system’s all about. I make you do things that you would never be able to do before. Playing the impossible.

Then there are other problems in the studio. I just finished doing ten spots for Miller beer. Years ago, we never had to raise our foot to play. I never played heel up. I always played with my foot flat because the engineers had ears! You’re not going to fight 50,000 watts of power. I never had to play loud. I played loud enough that the engineer could get a clear shot at me, but not to the point where I was distorting my sound. These kids in the studio now don’t know what distortion is. They come in with these Mack trucks full of amps. When they play a note the whole place shakes. You can’t fight that.

The engineer that I did the Miller commercials for put my drums through a limiter immediately. That cuts my sound way down. I had five minutes of this and got off the drums thinking, “I don’t have to take this.” I called the engineer over and said, “What are you trying to do to me? This is all against musical theory. It’s an easy piece. Why do I have to bang so loud?” He said, “Well, I want to get a good kick back.” I said, “You can get that later in a mix, Buster. You’re not going to break my legs.” That made me realize that times have really changed. Advertisement

SF: It seems like all the engineers and producers want all of the drummers to sound identical. It wasn’t like that in the ’50s and ’60s. Do you remember when that started to change?

GC: I was the only drummer who stayed with calfskin heads because I’m a brush player. My whole set was calfskin. As soon as I started to record I used plastic. I had three sets of drums. When I was hot, two of them were stolen. I had one set for rock, one set for “white” music—which is Robert Goulet, Perry Como or the Jack Armstrong All-American trying to be rock ‘n’ roll. All the sets were Ludwig. I wouldn’t use anything else. They gave me a $ 1500 set in 1963 and I never bothered them for another set. I don’t need a new set. I love what I’ve got. The old vintage drums are the greatest. The change you’re talking about was in ’74, ’75, ’76. Around in there the snare drum was lost. There were no highs on the snare anymore. Some guys muffled it down so bad or took the snares off it so it sounded like a tom-tom. That originated in Philadelphia with the “fatback”; “2” and “4” played really “fat.” But, there was no texture. No coloring. No emphasis. No highs on any of the playing. That’s what I miss. The drums now sound like a set of five tom-toms. That started with a couple of screwball engineers.

Years ago it was completely different. The engineer’s job was to hear the music, record the music and shut up. Those guys never got involved in production. Then you got these young guys who are really frustrated musicians. They start producing. That started about 1971 where half the engineers were producing side groups of their own on studio time, trying to make a hit, which is fine. But then it got to where an influx of producers came in who didn’t know what they were doing. Then the engineer would be a great help to them. It just got out of hand. They went on a supreme ego trip where they wanted to take part in the record, and some acts let them. Sometimes they got a hit. Sometimes they didn’t. As a producer, I would be resentful. There are a lot of good engineers out there. You’ve got to have good ears and it does help to read music. But, it doesn’t help to read music when you’ve got groups that don’t read!

One thing I try to impress on my students is that wherever you first make your mark, that’s probably where you’ll stay. If you’re with a group and you’re doing an original, and you go into the studio and you’re lucky enough to get a hit—stick with the band. You’re not going to move from that group to studio work. That group goes in as a whole; they die as a whole. You’re not going to step out of that group. Look at Santana. Look at Graham Lear. Great drummer. He’s stuck with groups. Mark Craney with Gino Vanelli. He’s stuck with that. If you want to be a session player, don’t get tied to a group. Advertisement

Another trick is: Don’t worry about money too much. If you worry about money it interferes with your playing. I made more money by mistake than I did trying to make money. I didn’t even know how much money I made and I didn’t give a damn as long as my family was okay. Sometimes you’ve got to find yourself. Play with a group. Realize you made a mistake and try to break into studio work where you can really make it.

Then your problems just start because then there’s the attitude of studio playing. There’s consistency. There’s one takers, two takers and half-hour takers. If they’re going to do a three-hour session and two sides, you’ve got time to experiment. But when you get into commercials, it’s Chart—Read—Out. That’s it! You get hooked on that because of the money. The most boring years of my life were doing commercials. I hated playing a 60-second spot and having to go in and wail. Then you listen back and as you’re wailing your butt off an announcer says, “Prudential Life Insurance. I’ve got a piece of the rock.”

SF: We were speaking earlier about a time in your career when you were very successful and you started drinking heavily. Why did you get into that and how did you get out of it?

GC: It was a question of feeling sorry for myself. I’m not a sociable drinker. I’m not a sociable guy. Let’s face it. I don’t like everybody.

I used to hang out at bars to eat. I never drank between sessions and I hardly ate between sessions. When I came home I’d sit in the kitchen by myself with a fifth of Scotch, trying to relax. I was the type of studio musician who’d do a date and never know what I did. Out. Next. My wife wasn’t allowed to call me on a date. My registry wasn’t allowed to call me. I gave my soul when I worked. Advertisement

I’d come home every night at maybe three or four o’clock in the morning and I’d have to get up at nine in the morning. I couldn’t sleep because I was so worked up from playing all day. My first drink would knock me on my ass and I’d be drunk. Then I’d drink the whole fifth. I never had a hangover. I’d get up the next morning and go to work. I considered that being a pro; to kick the hell out of myself and then go back to work.

Then I started getting very, very salty and very insulting to my family. I wasn’t a good father and I was a lousy husband. I was a lousy human being. That was the greatest hurt I ever had—realizing that I could be that bad. Six years ago, on July 13, I said, “That’s it. I’m not going to do that anymore. I don’t want to drink anymore. Why put everybody that I love so much through all this, when it’s only showing me how inefficient I am?” So I quit.

SF: Did you substitute anything for the drinking?

GC: I think I substituted my teaching. I love my teaching. A lot of people say, “How can you do that?” I became a completely different human being. I like people now who are listeners. I like to be able to share my experiences. I don’t just teach. It’s a whole philosophy. It’s a way of life for me. I want to be the greatest teacher in the world, and the only way I can do that is by getting the greatest pupils in the world. Advertisement

SF: Are you finding that your students have challenges that you didn’t have?

GC: Yeah. We were innovators. We had drummers to follow and we were smart enough to not only jam the blues. We’d jam on different tunes, like “How High The Moon,” “Cherokee” and all that stuff. And everybody played differently. A lot of these kids are locked into cover versions. I went over to one cat’s house and they were jamming to the Pepsi Cola or Dr. Pepper commercial. Now, that’s a shallow way of life. When you play exactly what’s on the record, that doesn’t require any creativity. It’s like doing nothing. Al though that’s a way of life for some kids, I’m hoping that someday they’ll realize that they’re only spinning their wheels. They’re not getting anywhere. I’m positive that everybody in the world has something to donate; something to say. I blame it on the educational system in America. And I blame it on parents. The kids go out and get high because they’ve got no strong fathers and mothers.

I’ll give you an example of the deficiency in the schools. There was a little town in the Midwest, giving tests to the school kids. The PTA noticed that the teachers were misspelling a lot of words on the tests. One PTA member said, “Why don’t you retest your teachers?” They did and found that a good percentage of them were functional illiterates. They could barely read or write English.

I see the results of the school system in my teaching studio. A lot of my pupils come to me thinking they can just get by without working. But I’ll be a son-of-a-bitch—when I give a lesson, you’re going to play it! And I’m going to keep your ass on it until you play it right! There’s no last minute cramming. But they’re not used to that. One college kid said to me, “Gary, you’re giving me a hard time, man. I’m not used to the concentration you’re asking of me. I’m not used to the discipline you’re demanding of me. I’m not used to listening to somebody as much as I have to listen to you.” I said, “Well, man…that’s your problem! What are you? A clone?” It’s sad. That’s what you’ve got out there. It’s all over the world.

Advertisement

I see the results of the school system in my teaching studio. A lot of my pupils come to me thinking they can just get by without working. But I’ll be a son-of-a-bitch—when I give a lesson, you’re going to play it! And I’m going to keep your ass on it until you play it right! There’s no last minute cramming. But they’re not used to that. One college kid said to me, “Gary, you’re giving me a hard time, man. I’m not used to the concentration you’re asking of me. I’m not used to the discipline you’re demanding of me. I’m not used to listening to somebody as much as I have to listen to you.” I said, “Well, man…that’s your problem! What are you? A clone?” It’s sad. That’s what you’ve got out there. It’s all over the world.

Advertisement

I’m trying to tell my students that unless you’re a listener, unless you’re sensitive. I don’t care how good you play—unless you’re aware of somebody else’s presence and want to give to somebody else, then you aren’t going to make it. Maybe you’ll make money, but you’ll never be happy.

SF: I’ve been told that “spirituality” has nothing to do with drumming.

GC: It has everything to do with drumming. I’d be as big a clone as anybody else if I hadn’t taken God in as a partner in my life. He’s sitting right here. I tried to kill myself a lot of times from depression until I found God and myself. Now I’m not afraid of anybody. I’m very, very religious. I don’t cheat. I don’t lie. That’s why I can be as honest as I am, because I’m really not afraid. I’ve got Him right there. I thank God constantly that he gave me such a damn good musical career. A little love of God will give you the security of not being afraid to express yourself. It’ll also give you the discipline to try new things and to practice what you’re learning. It’s a much more relaxed understanding of yourself and other people. I don’t care if you’re a Buddhist or anything. But, to live without religion, to live without belief—that’s living without hope. And to play without some sort of security within yourself is hopeless.

SF: Do you discuss spiritual topics with your students?

GC: Yes I do. I know when a kid is confused. If I can’t help him I get him professional help. I send some kids to psychiatrists. When I was young I used to talk a lot with two very dear friends: Pee Wee Erwin and George Wettling. I was always trying to learn something. Not only about music. Music was my first love, but, I figured I can’t play unless I’ve got something to say. And I ain’t going to have nothing to say if I’m ignorant! Advertisement

I had no education. I ran away from home when I was young and spent 10 to 12 years on the road. I lived by myself. I’m a self-made guy. I won the Gene Krupa contest when I was 14 and traveled with Gene for a little while. I couldn’t stand the way he played but he was a nice guy. Then I did most of my work in the Midwest. I spent half my life on the road. In a way, I was the same as these kids today. Party, party, party. But, to me, a party was playing. Not getting high. Not picking up chicks. I had all the chicks I wanted. Any drummer can have a chick.

People are so celebrity conscious. They kneel to you because they think you’re somebody and they’re not. That can get to you. You feel like King Kong; like you’re really something. But, meantime…you ain’t nobody.

There are all types of people who thrive on knowing you because you write for a magazine. Or knowing me because I was with Burt Bacharach. I feel sorry for them. You’re doing your job and I’m doing mine. They don’t realize that. I visited a guy one time and he asked me, “Did you bring your drums?” I said, “No. You’re a garbage collector. Did you bring any garbage?” Why don’t people realize that the only way this world will work is that you’ve got to have bridge builders, people who build big buildings, plumbers… you’ve got to have everything in the world. Everybody who’s doing what they’re doing is helping. Advertisement

SF: It’s scary when people identify themselves as “drummers” instead of human beings who play drums.

GC: That’s the whole word. I’ve had hundreds of offers to be interviewed. But, at a very young age I realized that drums is what I do best. That’s a very private thing, that’s for me. Leave me alone and let me live my life. That’s another reason why I never allowed myself to be put in front. You have to have enough within yourself. Drumming is a way of expressing how you feel. If you’re ignorant, it’s going to show in the way you play. If you’re smart, that will show too. Being a good drummer is not just banging. Being a good drummer takes everything you’ve got, including attributes like sensitivity and the desire to please. That’s a drummer.