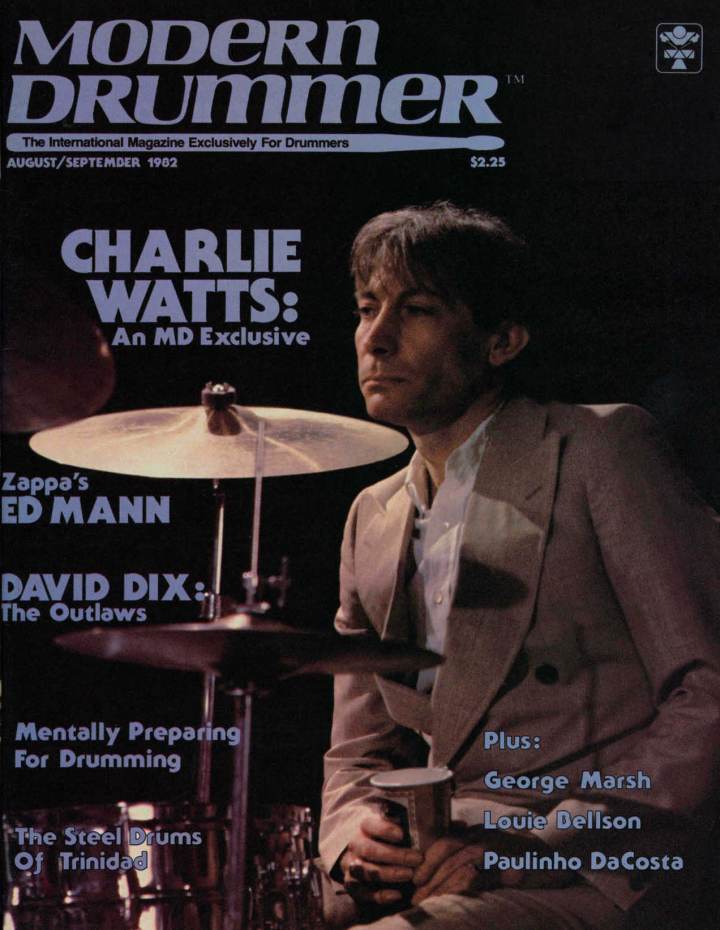

Charlie Watts

Editor’s note: The following articles on Charlie Watts are the result of over two year’s worth of effort on the part of MD. There were numerous phone calls to record companies and management offices, where the answer was always the same: “Charlie Watts does not do interviews.”

Last fall, while the Rolling Stones were on tour in America, Charlie met up with his friend (and MD Advisory Board member) Jim Keltner, who persuaded Charlie to talk to us. (Thanks, Jim) He agreed to speak with MD’s Robyn Flans in L. A., but it was only after Robyn followed him to San Francisco that he finally sat down in front of a tape recorder.

A month later, MD Managing Editor Scott K. Fish set up a meeting with Charlie and E Street Band drummer Max Weinberg. Again, Charlie agreed to let a tape roll. So here then is Charlie Watts who, although he actually spoke to us twice, began each session by saying, “I don’t do interviews. But we can talk if you want to…” Advertisement

After spending six hours with Charlie Watts, it was clear that he just doesn’t relish speaking about himself. I quickly realized that it would be necessary for me to turn to history books and others’ accounts to fill in the blanks that Charlie takes little pleasure in recalling.

Everyone who has written about the Rolling Stones, from journalists to the Stones’ own personal aids and cooks, has very little to say about him. This is not because Charlie is nondescript, but rather because he lives a very quiet life while off tour, keeps to himself and his family (his wife Shirley of seventeen years and their daughter) and does not partake in the much publicized activities of a “rock star.”

“I probably was a typical musician, but I wasn’t, and am still not, a Rolling Stone. I mean, I am because that’s what I do, but the other stuff is bullshit. I don’t know what the Rolling Stones are. For that you should talk to someone else other than me. I don’t know what they are. To me, they’re friends of mine. They are whatever you’ve read and they’re worse and they’re better. I never read the bullshit in the papers and I don’t have to hide in hotel rooms. I used to do that and I hated it. The worst time in my life was about the time the Rolling Stones became like the Beatles, I suppose. There were girls screaming and carrying on and I couldn’t stand it because I thought it was silly. I loved it for what it meant and what the band was doing, but I couldn’t stand not being able to do anything. I hated that. That doesn’t mean anything and I never wanted that. I’m just not interested in that. The only time I love attention is when I walk on stage, but when I walk off, I don’t want it. For the band, I want everyone to love us and go crazy, but when I walk off, I don’t want it. I guess I want both worlds. I never could deal with it and I still can’t. I don’t know how Mick does it. He’s an incredible man. So is Keith—an amazing guy. I don’t know how they do it, I’m serious. Like doing so many interviews. This is the only time I’ve so much as spoken to a journalist this whole tour and the reason I’m doing this is because drumming is something that I love.” Advertisement

He refuses to acknowledge his own musical contributions, continually downplaying his abilities. In an interview with Rolling Stone (11/12/81) Keith Richards says, “I’m continually thankful—and more so as we go along—that we have Charlie Watts sittin’ there, you know? He’s the guy who doesn’t believe it, because he’s like that. There’s nothing forced about Charlie, least of all his modesty. It’s totally real. He cannot understand what people see in his drumming.”

Whether Charlie understands it or not, the fact remains that he is often considered the model of what a rock drummer should be. Pick up a copy of The Village Voice, for instance, and look in the back where bands advertise for musicians. Invariably there will be a couple of ads that say something like: “Charlie Watts-style drummer wanted for rock group.” Journey drummer Steve Smith had this to offer about Charlie’s drumming: “When I first listened to Charlie Watts as a kid, I didn’t hear a whole lot there. It was because I was really unaware of what he was really great at, which is just an incredible feel. Now, I love the way he plays, especially after seeing him and doing those gigs with them. His time is really steady and really solid and his feel is the nastiest rock and roll feel I’ve ever heard. As a kid, I was totally into chops and I didn’t appreciate just a simple feel. I was impressed by the flash, and I wasn’t listening deeply enough. Now I have a totally different attitude. The bottom line is how it feels and what you can get across, emotionally.”

Charlie disputes that he has his own style or that there is anything special about what he does. “They (the Stones) developed it for me,” he told me. “I play as well as I can with this band and they happen to be very popular. But anyone can play like I do, yet that’s what I love about it in a way. Anyone can do it, really. Maybe they can’t do it the way I do it and it is no big deal to do it, but not anyone can play like Max Roach. You can’t play like Joe Morello. Not many people can play like that guy and there aren’t many people who can play like Jake Hanna. There are very few people in the world who can play that good. There are very few people in this world who can play like Louis Bellson. But there are a million kids who can play like me. They’re not me doing it, but they can play like it. I can play like Al Jackson, but I’m not him doing it. But to play like Joe Morello is something else. There aren’t many people who can play 5/8 time and 16/4 and all that, and I mean, play it. There are a lot of people who can play like Al Jackson, but they’re not Al Jackson and never, ever will be. They’ll never be as good as he is, but they can actually play those things. I think Al Jackson is as great as all those people I’ve mentioned, but what I’m saying is that he taught people how to play those things. I’ve heard girls play exactly like me and they can play everything. They’re not me, but they can play everything. There are very few people in this world who can do what I’m talking about. You see, the audience doesn’t really want to hear me play ‘Honky Tonk Woman.’ They want to hear the song, primarily, with me doing it, because the song is more important than me.” Advertisement

Jeff Porcaro responded: “No. Wrong. Not anybody can do what he does. I know if I sat down and played with the Stones, I would be trying to play like Charlie Watts. I know myself as a professional drummer and I would sit down and say, ‘Okay, now play simple here, be sparse and don’t do that fancy fill because Charlie wouldn’t do that.’ But my snare drum wouldn’t sound like Charlie’s because that’s a whole other unique sound.

“I think Charlie Watts is a great drummer for pretty basic reasons. I like his time, I like his groove and I love what he plays with the Stones. When you look at Charlie and what he plays, it seems like some of those technical facilities that he doesn’t have, makes for the sparseness that he creates when he plays and that you hear. There are no rules or anything and nobody plays like him but him.”

So how did Charlie become involved with drums to begin with? “Blame it on Chico Hamilton, I suppose. When I was twelve, I heard Chico Hamilton with Gerry Mulligan playing ‘Walking Shoes’ and I played it on a skin of a banjo. I used to play brushes like Chico Hamilton. Well, not like him, but that was the inspiration anyway. After that, I heard Charlie Parker and that was it. It was all over. It was the music really, that got me going, because I’m not a drummer. I’m not a drummer because I never learned to play the drums. I’m not like the people I admire. They learned and I never did. I just sat and played drums like they played them. Max Roach can play anything and I sat and copied it. When I heard Charlie Parker play, I would play like Max Roach or Roy Haynes.” Advertisement

Charlie was so enamored of Charlie Parker that in 1962 he wrote a book called Ode to a High Flying Bird, which was in the vein of a children’s book and illustrated by Watts. It featured Parker as an actual bird hunched over a saxophone so that the body blended into the head. Unfortunately, the book was never issued in the U.S..

“When I had the honor to go to New York, that was it! All I wanted to do was go to Birdland and I was lucky enough to get there before it closed and that was it for me. I still walk down 52nd Street. I know it’s not the same anymore, but I do it. It’s just something that really meant something to me as a kid, listening to Charlie Parker, and to think that he lived there and walked down that street and played there. I walk there, even now, at forty years of age. I can imagine being Sid Catlett, walking down that street with the drums on my arm, but it’s just a dream world. But it’s a dream world that I love, and if I ever lose it, I’ll stop playing drums.

“Among my favorite drummers is Dave Tough. Nobody knows how great he was. There’s a lot of people I admire and they are what I try to be, but I’ll never be that good. In my life, I’ll never be that good because I’m not that good. Tony Williams is one of my favorite drummers. That’s how someone should look when he plays the drums. He is a fine looking man and a fine looking drummer. He is one of the innovators as far as I’m concerned. To do what he did at the age of nineteen, he must be somewhere else. To me, some of the finest drumming came from Jerry Allison [one of Buddy Holly’s Crickets]. He is one of the finest drummers and very underrated. He plays songs; he doesn’t play the drums, and that’s what I’d love to do. I can’t do that, though, because I’ve got Max Roach, who is a drummer, inside of me. Yet I’ll never be Max Roach and I’ll never be Jerry Allison. Jim Keltner, for instance, can play the drums. Jim can read and he’s a fine musician. I’m not a fine musician. I play the way I do and I happen to be lucky enough to be in a band that is very popular, and that’s all. If I wasn’t with a popular band, I’d be one of a million kids out there.” Advertisement

Jim Keltner disputes this: “Most drummers, including Charlie, feel guilty when they don’t read music, and they feel that they’re not real musicians. Charlie is one of my favorite drummers because of his simplicity, his sound and his time feel. The thing is, that Charlie is playing with virtual brothers, and it becomes second nature. He doesn’t know what he does. But he doesn’t have to know what he does.

“If you listen to the old records, particularly, you hear rushing and dragging and you hear him play a fill and it just barely makes it. When you talk about a drummer and you say those two things about him, right away you think, ‘Wait a minute— that’s wrong.’ A drummer is about time and about playing with taste and fills and all that, and that’s what the civilized musical world expects from you. With Charlie, he’s always broken those rules, but he’s done it innocently and also with a magic band, and it works. He’s had a chance to refine that up to the point where the last couple of records, it’s just pure, out and out, great rock and roll drumming.”

“Drumming, to me, has always been fun,” Charlie explains. “That’s why I couldn’t play with Doc Severinsen and the Tonight Show Band. I couldn’t do that gig. I couldn’t cover that gig and not read. It was always fun to me, sort of a hobby. It wasn’t really a hobby, but something I loved and it still is a lot of fun. It’s become something I love, more than when I was a kid, really. I was sort of dragged into it because it was fun and I was able to play for a living.” Advertisement

In The Rolling Stones—The First Twenty Years, his mother recalled, “Charlie always wanted a drum set, and he used to rap out tunes on the table with pieces of wood or a knife and fork. We bought him his first drum set for Christmas when he was fourteen. He took to it straight away, and often he used to play jazz records and join in on his drums.”

“I was just a teenager when I first got interested in drums,” Charlie said in the same book by David Dalton. “My first kit was made up of bits and pieces. Dad bought it for me and I suppose it cost about twelve pounds. Can’t remember anything that gave me greater pleasure and I must say the neighbors were great about the noise I kicked up. They had a sort of tolerant understanding… ‘Boys will be boys’ kind of thing! I don’t think I ever wanted to play any other instrument instead of the drums. I marvel sometimes even now at the way guitarists can get such tricky little phrases by just quietly using their fingers, but drums are for me.”

Seated with me, he recalled, “I practiced a lot but I never had lessons. I hated play ing to records. I used to try, but I could never really play to records. I can’t over dub drums either. I hate doing that. Sometimes you have to, but I can’t do it very well. I taught myself by listening to other people and watching. I’d go and see every American who came to England. To me, how an American plays the drums is how you should play the drums. That’s how I play. I mean, I play regular snare drum, I don’t play tympani style, although I know guys who play fantastically like that. I play march-drum style. Most rock drummers play like Ringo; a bastard version of tympani style. In reality, that’s what it is because tympani style is fingers and most rock drummers play like that because it’s heavy offbeat.” Advertisement

In Dalton’s book, Charlie reminisced: “Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies were the start of rhythm and blues in this country (England). If things were as they should be, Alexis would be right at the top. I met Alexis in a club somewhere and he asked me if I’d play drums for him. A friend of mine, Andy Webb, said I should join the band, but I had to go to Denmark to work in design, so I sort of lost touch with things. While I was away, Alexis formed his band, and came back to England with Andy. I joined the band with Cyril Davies and Andy used to sing with us. We had some great guys in the band, like Jack Bruce. These guys knew what they were doing. We were playing at a club in Ealing and they (Brian, Keith and Mick) used to come along and sometimes sit in. It was a lot different then. People used to come up on the stand and have a go, and the whole thing was great.”

How did he become a member of the Rolling Stones in 1963, I asked. “Pure accident,” he replied. “There were many bands in London and I happened to be free at the time I joined them. That’s my opinion. Other people have another. I played with Mick and Keith when I played with Alexis and everybody knew each other. Alexis wanted a sort of Charlie Mingus r&b band and he’s still the same. I love him. He never stops moving. Marvelous man. But I had played with Alexis for about a year or nine months and then gave up my chair to Ginger [Baker] because I thought he was a better drummer than I was. I played with three other bands and I was asked to join Mick and them. I’ve lived with them ever since, for twenty years. I was between jobs as a designer and I used to leave their apartment and go for interviews while I played with them. I did that for about six months. Then, all of a sudden, I made more money doing that than I could make being a designer and suddenly I became a profesional musician, whatever that is. I’m still not, in my opinion, but I had to join the Union suddenly.”

In Our Own Story by the Rolling Stones, a book published in 1965, Watts had elaborated on the subject: “The scene was growing bigger week by week for Alexis. I loved the work, but it got to be too much of a strain after a while. So I sort of backed out and worked with one or two other groups, meeting up with Brian and Mick and Keith from time to time. Advertisement

“So they asked me about kicking in with them. Honestly, I thought they were mad. I mean they were working a lot of dates without getting paid or even worrying about it. And there was me, earning a pretty comfortable living, which obviously was going to nosedive if I got involved with the Stones. It made me laugh to think of them trying to get me in with them too. “But I got to thinking about it. I liked their spirit and I was getting very involved with rhythm ‘n’ blues. I figured it would be a bit of an experiment for me and a bit of a challenge, too. So I said okay, yes, I’d join. Lots of my friends thought I had gone stark raving mad.

“See, the thing with me is that I’m not really much of a worrier. I do get involved on stage, of course, especially when I think something is going wrong, but that’s all. I reckon tomorrow can look after itself.

“Only thing that had me wondering, once I’d made up my mind, was the fact that the Stones were so disliked inside the jazz world. I’d heard people talking about them—and it’s true to say nobody had a good word for them. They were complete outsiders. Nobody wanted to know about the great sound they were making— because everybody was too busy looking on them as just a gang of long-haired freaks. And I certainly wasn’t keen on letting my own hair grow at that time just for the sake of being a member of the group. Advertisement

“But this bunch of outsiders, what people called ‘lay-abouts,’ struck me as having a pretty good future. I thought the atmosphere they got going simply had to make it big one day …”

Of course, Mick and Keith go back to childhood. The story is that they met on a train on the way to school in 1960 after not having seen one another since they were kids. Under Mick’s arm was an album by Chuck Berry, which sparked a stimulating conversation. Finding they possessed similar musical tastes, they began to experiment together. It was 1962 when they began to frequent the club in Ealing where they came across Brian and Charlie. Brian, more into jazz-blues than the Chicago blues that Mick and Keith favored, joined forces with them.

In an interview with Bob Greenfield in 1971, Keith said, “I’ll tell you how we picked Charlie up. The R&B thing started to blossom and we found Charlie playing on the bill with us in a club. There were two bands on; Charlie was in the other band. We did our set and Charlie was knocked out by it. ‘You’re great, man,’ he says… We said, ‘Charlie, we can’t afford you, man.’ Because Charlie had a job and just wanted to do weekend gigs. Charlie used to play anything then—he’d play pubs, anything, just to play, cause he loves to play with good people. But he always had to do it for economic reasons. Advertisement

By this time we’re getting three, four gigs a week. ‘Well, we can’t pay you as much as that band but…” We said. So he said okay and told the other band: ‘I’m gonna play with these guys.’ That was it. When we got Charlie, that really made it for us.”

In those days, the Stones were basically a rhythm and blues group, and their material was made up mostly of songs by such artists as Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley. Their first English single was Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” and their first single to do well on the American charts was Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away.” The Stones’ first album was made up of a lot of the standard r&b favorites of the day, with only a few original compositions.

“The Last Time” was the first original Stones song to be released as the A side of a single. This was followed by “Satisfaction” and “Get Off Of My Cloud,” also written by Jagger and Richards. These songs established the pattern for the Stones’ style—they were written around a basic, simple riff. Advertisement

One of the secrets to being a successful member of a group is to concentrate not on yourself, but on the requirements of the music. An often-heard comment about Charlie Watts is that: “He is the perfect drummer for the Rolling Stones.” After observing the characteristic structure of Stones’ songs, it became obvious how Charlie’s drumming complements the music. If a song is based on a simple, repeating riff, the drum part must be equally simple and repetitive. Busy patterns, fills, and subtle colorings are not appropriate. Indeed, there is nothing subtle about the Stones. Their power comes from their directness—basic chord progressions, basic rhythms, and even basic lyrics. Charlie provides basic drumming.

As the Sixties progressed, the Stones’ music gradually shifted from the r&b influence towards a more pop sound, with tunes such as “Lady Jane” and “As Tears Go By” finding their way onto albums. The group even experimented with “psychedelic” music, producing a rather unmemorable album called Their Satanic Majesties Request.

Beggars Banquet, in late 1968, marked the return of the r&b influenced Stones. Since that time, the band has stayed pretty close to its roots, although there have been other influences. One important change occurred in 1969 when Mick Taylor replaced Brian Jones as guitarist. Taylor had a clean, jazz-influenced style which contrasted well with Richards’ raunchy rock sound. The difference is very obvious on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” from the Sticky Fingers album. The tune starts off with Keith Richards ripping off a few raw rock licks, before settling into the tune’s main riff. Charlie plays basic, driving rock. The second half of the song turns into a jazz jam with a saxophone solo, followed by a Taylor guitar solo. Charlie accordingly turns into a cross between Tony Williams and Mel Lewis—maintaining a quarter pulse on hi-hat, while pulling a variety of colors from his cymbals. As always, Charlie produced exactly what the music called for. Advertisement

In ’75, Ron Wood replaced Taylor, and because Wood plays so much like Richards, the group has leaned more heavily on basic rock. One notable influence of the last few years has been reggae, and again, Charlie has successfully mastered the style.

When asked what bass player Bill Wyman thinks gives the Stones their characteristic sound, he answered in Guitar Player (Dec., 1978): We have a very tight sound for a band that swings, but in amongst that tight sound, it’s very ragged as well. Every rock and roll band follows the drummer, right? If the drummer slows down, the band slows down with him or speeds up when he does. That’s just the way it works—except for our band. Our band does not follow the drummer; our drummer follows the rhythm guitarist, who is Keith Richards. Immediately you’ve got something like a 1/100th of a second delay between the guitar and Charlie’s lovely drumming. Now, I’m not putting Charlie down in any way for doing this, but on stage, you have to follow Keith… So with Charlie following Keith, you have that very minute delay. Add to that the fact that I tend to anticipate a bit because I kind of know what Keith’s going to do. So that puts me that split second ahead of Keith. When you actually hear that, it seems to just pulse. You know it’s tight because we’re making stops and starts and it is in time—but it isn’t as well. Sometimes the whole thing can reverse. Charlie will begin to anticipate and I’ll fall behind, but the net result is that loose type of pulse that goes between Keith, Charlie and me.

“(It began) probably as a matter of personality. Keith is a very confident and stubborn player, so he usually thinks someone else has made a mistake. Maybe you’ll play halfway through a solo and find that Keith has turned the time around. He’ll drop a half- or quarter-bar somewhere, and suddenly Charlie’s playing on the beat, instead of on the backbeat—and Keith will not change back. He will doggedly continue until the band changes to adapt to him. He knows in general that we’re following him, so he doesn’t care if he changes the beat around or isn’t really aware of it. He’s quite amusing like that. Sometimes Keith will be playing along, and suddenly he becomes aware that Charlie’s playing on the beat, and he’ll turn around and point like, ‘Aha, gotcha!’ and Charlie will be so surprised and suddenly realize he’s on the beat for some reason, and he hasn’t changed at all. And then he’ll be very uptight to get back in, because it’s very hard for a drummer to swap the beat. So it’s a mite funny sometimes, but it does happen, especially on the intros. Some of the intros are quite samey sounding. I mean, if you’re doing a riff on one chord with the inflections that Keith uses, and you’re not hearing too well with the screaming crowds, you cannot tell if you are coming in on or off the beat. ‘Street Fighting Man’ is a tune that tends to happen on. He’s got monitors, but in those circumstances it’s very difficult to hear accents—the difference between the soft and hard strokes. The problem is that Charlie is often totally unaware that he’s on the wrong beat, and he shuts his eyes and pulls his mouth up, you know, and he’s gone. You can’t even catch his eyes because they’re closed. Someone has to go up and kick the cymbal. I don’t think that happens too often with other bands. But I think that’s a little of the charm of the Stones. They’re not infallible, and we know that. Everybody else might as well know it, too.” Advertisement

In Guitar Player (11/77), Keith Richards said he plays off of Charlie’s accents. “We tend to play very much together. I have to hear Charlie and I think he has to hear me. I love playing with Charlie; he knocks me out every time. Sometimes I don’t see him for six months or so, and we get together and he’s better every time. He must practice so much.”

“I do practice every day if I’m not playing,” Charlie told me. “I sit and watch television and practice. I never did that when I was a kid, so I have to do it now. I’ve learned more about what I’m doing now than I did then.”

As far as the recording end of it, Charlie explains, “We don’t lay tracks. We always play as a band. We very rarely overdub drums and bass and such. I have all and nothing, as far as creative choice, which means, I just sit there and play the song. Mick or Keith will say, ‘No, that’s horrible,’ and I think, ‘Yeah, it is horrible and all I should do is nothing; just play.’ You can’t play like Max Roach over ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash,’ so you just sit and say, ‘You’re right.’ And then I’ll do something and they’ll say, ‘That’s great, keep doing that.’ So it’s all or nothing. I have as much say as anyone in what I do. Advertisement

“A lot of the recording end for me is the engineer and mixer, which is often Mick. It’s the engineer who makes my drum sound amazing. I don’t do anything other than I do on a bad night and he makes them sound great while I just do the same thing. I never tune drums. It’s one of the blind spots I have. I just hit them.

“I’m fortunate that I don’t really have to stake a claim on anything because the claim has already been made just by everyone being there. It is what it is, with or without me, but it happens to be with me. I don’t really have to make a point of making my impression. I don’t ever think of it that way. I’ll say the drums should be louder or that sort of thing, but if someone says, ‘No, they’re too loud,’ I don’t really care. I don’t really have that sort of mind to carry the songs through either. I can’t stand mixing. I stay around for it, but I can’t stand it. It’s boring and bloody hard work as well. I guess I don’t understand it either.”

When I mention how much more predominant the drums have been on recent recordings, he laughs, “The drums are awfully loud, aren’t they? They make it sound like more than I am, but I’ve always been loud.” Advertisement

Charlie has always preferred Gretsch drums, although the first set his dad bought him was a Ludwig, which he used on the album he did with Rocket ’88. He keeps his Gretsch set to the bare essentials, however, with just four drums, about which he says, “I don’t use the tom-toms much. I’m not a virtuoso, you see. I just try to play the rhythm. I can’t take fills and I can’t play four-bar breaks and all that, but what I do I try to make as fine as I can make it. Oh yeah, I get it on occasion,” he adds modestly, “But to play like Frank Butler . . . I don’t have that finesse and I never will ever have it in my life. That’s something else, and that, to me, is a drummer.”

After twenty years, Charlie maintains a simple attitude about performing live and playing with the same people. “Every gig is neither bad or good. I always want it to be better than the last one. It’s never the same any night. Even if you play a cocktail lounge or a Bar Mitzvah every night. It’s never the same, really. You play ‘Hava Nagila,’ and I’ve done that, and it’s never the same. If you do that four times a week, you get a good ‘Hava Nagila’ or a bad one, whatever band you’re in. Sure, I’m sure if you’ve done eighteen Bar Mitzvahs in a row, it can get the same. I’ve done about four of them. But the songs we do now are never the same. Of course, in some ways it is, it’s all three chords and all I play is two and four, but really, it’s never the same to play them. I just want to get to the end of it and make it as good as it can be. If people have trouble keeping it fresh every night, then they can’t like the people they’re with or the music they’re playing. It’s probably both.

“I hate touring and I hate going on the road and my first reaction to this last tour was, ‘How the hell can I go out there at forty years of age and do that?’ I didn’t think people would turn up to see it, but they did. I don’t think they really see me, though. They see the whole thing and I’m lucky enough to be part of it. I’d love to play in a lounge with a trio, but this band, I think, is one of the best and it can’t be beat at what it is and I’m lucky enough to be involved in that. But I’m only as good as the next gig I do. That’s how I’ve always seen it and I think the band is only as good as the next gig it does. With the accolades and everything, it’s very easy to sort of get comfortable. It’s a lovely thing to have, but it doesn’t really mean anything. It’s your next stop that is important and then the next one. And you just try to enjoy yourself while you’re doing it. But you don’t get the accolades if you’re crap, so that’s what I mean about this band—they’re damn good and I don’t care if people say they’re noisy. They are noisy. They make my ears hurt,” he laughs. “But they’re bloody good at being noisy and they’re bloody good at whatever they do. What I try to do is make it better and I try and help out the best that I can. Advertisement

“Musicians are the most selfish people in the world, actually,” he states. “The world revolves around them and all you live for is that two hours on stage and that’s all they have. A painter or a draftsman can work any time. It can be for five minutes or for a year. With musicians, it’s also a closed shop. They’re the most unwelcoming people, really. I’m not saying that they’re not nice people or intelligent, but it’s what they do. They aren’t the most open of people. I think it’s their attitude and I don’t think it’s ever going to change. So much for philosophy.

“As far as playing with the same people all the time, it’s no different than playing with others. I think Bill Wyman is an incredible bass player. Some people don’t know what he’s doing, really, but it’s right. You don’t really hear him actually half the time, or I don’t, but he’s right and very rarely wrong. He’s very comfortable to play with. I’ve never really sat and listened to the bass, though. We don’t sit and work out rhythm patterns or anything like that like some bands do. He plays to a song that Mick writes and I do the same thing and it just fits. He plays with other drummers too, that are fantastic players, actually, like I play with others. Bill is very comfortable, but Jack Bruce is comfortable to me too. Anyone who plays well is comfortable. Pete Townsend is comfortable to play with. I’m not saying he’s better or worse to play with than Keith, but he’s comfortable also.”

About his projects outside the Stones such as Rocket ’88 and the recording with Nicky Hopkins and Bob Hall, he says, “They’re just fun, aren’t they? The playing is no different, really. It’s another gig, isn’t it? That’s all and you have to do that one as best you can also. You just play. They’re all exciting. Rocket ’88 is great because it has four saxophone players, a trumpet and it’s lovely. It’s a different thing to play and it has a different sort of quality of playing. I don’t mean good or bad, just different. It’s great in its way and it’s fun for me to do, but it will never be that magic that happens. I have a great time with them, though. Advertisement

“I had a wonderful experience not too long ago in London when I played with a band and the saxophone player was Eddie Vinson and it was the most wonderful thing I’ve ever done. It was amazing and that guy is incredible. But you have to be as good as Steve Gadd to really cut it if you’re in that market. Luckily I’ve never been a market player. I’ve always played with a band.”

While that fact has been Watts’ security, he stresses that the public has become too secure with the likes of the Stones and there is a tremendous need for some new music on the scene.

“I thought this band would be together for five years. I don’t want to leave them or anything, but after five years, I thought, “Great, ten years, okay.” But it’s gone on and on and on. For me, it’s wonderful, but I’m just saying that I’d like to hear some more power. I still love Benny Goodman, even though music has changed, so it doesn’t have to take away from what exists, but there needs to be something new. Eighteen-year olds must play something other than Chuck Berry because it’s been done. You’ve got to have something for yourself. It’s got to happen. I don’t see it yet, and I don’t know why, but it’s going on and on like this. We’ve been going for twenty-five years and kids are still copying us and the Beatles after all these years. Honestly, there’s got to be something to it and I hope to God there is. It’s wonderful, but there’s just got to be something else. It won’t take away from what we are because we’ll still be the same.

“I love this band, but it doesn’t mean everything to me. I always think this band is going to fold up all the time—I really do. I never thought it would last five minutes, but I figured I’d live that five minutes to the hilt because I love them. They’re bigger than I am if you really want to know. I admire them, I like them as friends, I argue with them and I love them. They’re part of my life and they’ve been part of my life for a lot of years now. I don’t really care if it stops, though, quite honestly. I don’t care if I retire now, but I don’t know what I’d do if I stopped doing this,” he ponders. “I’d go mad.” Advertisement

Quotes from Guitar Player copyright GPI Publications. Reprinted with permission.