Bill Ward: Metal Drumming Godfather

“Oh no, I could never have imagined it,” says Bill Ward with a long pause of disbelief. The drummer is recalling last year, standing alongside his Black Sabbath bandmates, Tony Iommi and Geezer Butler, to receive the revered Lifetime Achievement Grammy. And he is remembering a half-century before now, when the legendary heavy-metal band recorded their first album. “I never really had any thought about the future,” he explains. “I only cared about making a good record.

The band’s premiere 1970 LP, Black Sabbath, followed by Paranoid a mere seven months later, delivered a one-two punch now considered to be the formative pillars of heavy metal. The debut opens with the sound of a drenching thunderstorm punctuated by a tolling church bell. Suddenly, the eerie tableau is shred by the demonic three-note theme of Iommi’s gargantuan guitar assault, bottomed by Butler’s throbbing bass and Ward’s thunderous kit flourishes. When vocalist Ozzy Osbourne finally enters, spinning a yarn of a face-to-face encounter with Satan, it’s clear heavy metal has arrived. If the hippy bands of that era were saying, “Spread love, it’s the Age of Aquarius,” Sabbath was warning, “Run for your lives; the apocalypse is nigh!”

Although sporadic building blocks of metal had hit record racks before 1970—including contributions by Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, and even the 1964 distorted power-chording of the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me”—no other band so clearly defined the ethos of heavy metal, both sonically and thematically, as Black Sabbath. Advertisement

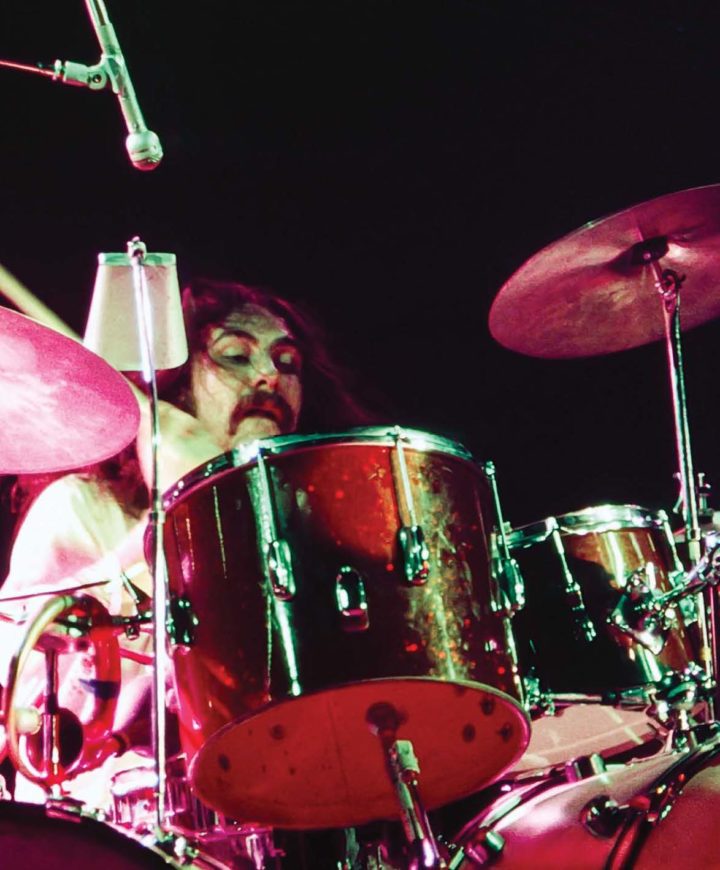

Ward ferociously drove the dark, occult-themed quartet, digging deep on the two-fisted grooves while embellishing around the massive monster riffs and drawing from his influences in blues, rock, R&B, and—though surprising to some—his love of early jazz heroes.

In that decade alone, Ward fueled the band through six additional highly successful LPs and tireless world touring, establishing them as one of the globe’s top acts. And in the following decades, their successful reign continued. Ward eventually departed the band in 1980. He subsequently manned the throne for shorter stints in 1983, 1984, and 1985, then for longer stays from 1997 to 2006 and 2011 to 2012. In addition, Ward released a string of solo albums, starting with 1990’s Ward One: Along the Way. Although Black Sabbath later folded in 2017, Osbourne has publicly expressed interest in future one-off concerts with the original lineup.

Today, at seventy-one years old (he turns seventy-two on May 5), Ward is as avid about drumming as ever, while actively engaged in composing and leading his two bands, Day of Errors and the Bill Ward Band. Summing up his long journey in the big time, the powerhouse drummer says, “Whatever I did on the first album, I was learning to become a better drummer beyond that. I strive for that. I’m still doing that: striving to be better than wherever I was a few weeks ago.” Advertisement

MD: In 2017, Rolling Stone placed Paranoid at #1 on their 100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time list. That speaks to its long-lasting influence.

Bill: I’m truly honored. Honestly, I give a lot of credit to our peers, other bands after us, who credited us. That really helped to bring Black Sabbath into a fortified place, as far as travelling through the ’90s and the 2000s.

MD: The band had become more focused on Paranoid—and with a stronger groove. A lot of the credit for that goes to you.

Bill: We were quickly getting better. After the first album, we were playing better venues and becoming more confident. We were becoming more outrageous: allowing ourselves to let go of previous influences and be more ourselves. I think that’s what happens with bands when they have a hit first record…I feel great about everything we achieved. One of the things I had to learn about myself is that I’m not a drummer.

MD: How’s that?

Bill: I play orchestration; I play back to what comes at me. I build structures around things. And I make allowances for the bass to sweep over me and for Tony to break through; they allow so much to happen. I never thought about “keeping a beat” in Black Sabbath. Some things needed a groove. But groove accompaniment seemed to work and then as soon as that stopped, I would move on to where else I needed to support things. Advertisement

“Just the other day, while playing with a friend, I would deliberately slow down where I could. I like to do those kinds of treatments, because it really brings out the balls in a song.”

MD: You’ve cited many classic jazz drummers as your main influences, including Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, and Louie Bellson. There is jazz influence in what you played with Sabbath, even though people see heavy metal as a polar opposite to jazz. Your bandmates were laying down solid monster riffs while you were responding, playing around it—syncopating, filling, providing fluidity—somewhat like Mitch Mitchell, but in a different context.

Bill: It’s totally like Mitch. And it’s like John Densmore—the way that he played between the Doors. He’s a remarkable drummer. I see him and Mitch Mitchell as orchestrational drummers also—and with amazing power. But it’s more than just the playing: it’s the emotion of the chord. If there was something that was so dynamic—with so much anger behind it—then I learned to produce anger from the drumkit.

Just the other day, while playing with a friend, I would deliberately slow down where I could. I would play half-time or just a really simple right-hand pattern—just so it would give the feeling that the track was slower than the tempo would actually be. I like to do those kinds of treatments, because it really brings out the balls in a song—playing “slow” behind something that also has huge chords. It’s different; it’s very menacing. And to create that, you also need the right partners. Advertisement

MD: Those slower chugging tempos, with huge gravity, were a Sabbath signature. It surely was never an on-top feel.

Bill: No! If it had been on top, it would have completely ruined everything. It has to be behind.

MD: The initial ’70s albums were recorded with the band playing together “live” in the studio and interacting. A lot of current metal recordings use excessive overdubs, sometimes with players laying down each track individually.

Bill: A lot of the musicians in the 1960s, including the members Black Sabbath, grew up learning how to play dynamically. We could play loudly or quietly. We didn’t have machines that did that for us; we had to produce that. Dynamics were everything. Even in playing at the high volumes of bands like Black Sabbath.

MD: There were also some more specific references to jazz on the debut, certainly on your intro to “Wicked World.”

“I love Day of Errors because I can play loud. I can be aggressive and be all the things that I was able to be in Black Sabbath.”

Bill: I stole that from Krupa.

MD: Talk about those jazz-drummer influences.

Bill: When I was a child, between four and five years old, I heard a lot of big band music. I was drawn to drummers, and particularly to Krupa. There was something about him that was “reckless.” Buddy, however, always seemed tight and professional. That didn’t put me off too much—I love Buddy’s playing. But there was something about Gene that was so…almost sloppy. And I was drawn to how he went about being so in-control, yet sounding out of control. Maybe not out of control really, but very listenable. Very attractive as a drummer. Where he put his kicks—some of them reminded me of Earl Palmer on Little Richard tracks like “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally.” I said, “Hey, I think I’ve heard this before!” Maybe he’d been listening to Gene as well. [laughs] Advertisement

MD: Also, you would often get away from the cymbals and snare and switch into sections using just throbbing toms, with an emphasis on the floor.

Bill: Oh yeah, I totally go there all the time. If Tony’s got a low note, I’m there, man. That’s a Krupa thing. I still listen to him today. When I talk to my drummer friends today, we’ll sit down and talk about Krupa. We don’t talk about us; we talk about the masters and swing music.

MD: You also slipped in some funky elements that gave the metal grooves a lift, suggesting that you listened to R&B and soul as well.

Bill: Well, I did. And I started listening to New Orleans funeral music when I was about six years old. I was drawn into the darkness of that music.

MD: The slow to-the-grave processionals?

Bill: I was drawn into both the slow and fast. And I started playing that. It’s such an infectious groove.

MD: You’ve cited one of your favorite Sabbath tracks as “Into the Void” [from 1971’s Master of Reality]. You were playing double bass then. What do you like about that track?

Bill: It’s that I have to hold everything on the ground. That thing can fly away, fly away like a tortured bird. I really have to hold it. What I do is—I’m going to let you in on a trade secret—I look at Tony’s left foot. I just work with his left foot and that’s how I keep my end of it on the ground. I have to keep it tight, because when we go into that busier, bigger part, in order to be impactful, I have to come from an almost sullen place; I’m not being “constructive” at all by adding anything in, because the band needs to make an impact when we do come in. I have to be very strict with my time and solid in the groove. And I can’t do little tom things; I have to stay away from the temptations of showing my skills, blah blah. Because that song is about the band, not me.

MD: Drummers naturally take in physical cues. That’s why an isolated studio booth with limited visuals can be restrictive.

Bill: I know that one well. Because I have to have contact. I was brought up playing with contact. The first time I went into the booth, when we made Black Sabbath, I felt as if I was drowning. I need to have my cues. I needed to see Tony’s fingers, I’ve got to see everything—the way he moves, the way he goes back and forth. It’s very important. Advertisement

MD: In the early tours, the drum miking, sound support, and monitors were primitive by today’s standards. In that ultra-volume setting, how the heck did you do it?

Bill: I had to play really hard. Especially when we started using the amplification we had in 1970. Fortunately they did have a sound system when we came to the United States, and that was the first time I felt like I could be heard. Other than that, I had to beat the crap out of the drumkit. We all had to kick the crap out of it. Mitch Mitchell had to do it. Some of my friends back then, like Ric Lee with Ten Years After—he pounded the drumkit. Corky Laing pounded the drumkit.

MD: With limited monitoring, it must have been difficult to keep the band together.

Bill: We were used to playing with each other right from the beginning. So going onstage, you could pretty much put any sound system up around us and we could play, because we had all the body cues, a lot of stage cues. In 1970, we did get some extra mics on my drumkit. And it wasn’t too much later that I had a speaker behind my ass—my own bass drum. I had to get used to that. But it didn’t stop my aggression; I’ve always played aggressively with Black Sabbath. You have to; the songs make you play aggressively.

I really didn’t pay much attention to the monitors. The only thing I really needed to hear was the very top of Tony’s high notes. Because in between introductions, he’d play very high and I couldn’t hear them. Sometimes I’d lose them, either from the wind blowing across the stage or different technical reasons. So again, I would have to watch because I had to come in and the whole thing was hanging on me. Advertisement

MD: As a godfather of metal drumming, how do you see the state of the art today, and for the future?

Bill: I like what a lot of the guys have done, including some of my buddies like Dave Lombardo, Gene Hoglan, and—back in the old guard—Johnny Kelly. I know a lot of guys and I admire every single one of them. I go and watch them up close and personal. I love what they’re presenting and moving forward to. I can feel the difference in what we were doing back in the ’70s and what they’re doing now—moving forward. Metal has its own brand. I hope this doesn’t sound cynical or dividing. But, real metal tends to not be about girl/boy; it tends to be about issues and about tragedy. And that’s where the rubber meets the road. There are a lot of bands that play loud but that I was never really turned on by; they were singing about a girl or something. I like bands that get down there, f***’n get in there!

Ward’s Current Setup

Drums: Gretsch Brooklyn Series (except snare) in Gray Oyster finish

• 8×14 Sonor Horst Link cast bronze snare

• 9×13 tom

• 10×14 tom

• 16×18 floor tom

• 18×18 floor tom

• 18×24 bass drums

Hardware: Gibraltar, including telescoping cymbal boom stands with counterweights

Heads: Remo Coated Ambassadors

Cymbals: Sabian

• Hi-hats: various choices in 15″ and 16″ sizes: AAX X-Plosion Hats; AAX X-Celerator Hats, sometimes with two or three rivets on under side edge; AAX Stage Hats; 17″ hand-hammered prototypes

• Crashes: Two crashes in various combinations from among: 18″, 19″, or 20″ AAX Metal crashes; 20″ Rock ride; 21″ AA Rock ride; 21″ Raw Bell Dry ride; 20″ or 22″ medium-heavy AAX crash

• Ride: 24″ HH Power Bell (sometimes prototype 26″ or 28″)

• China: 26″ sand-blasted finish prototype (on rare occasion)

Advertisement

Early-’70s Black Sabbath Setup

Drums: Ludwig in Black Oyster finish, 3-ply mahogany/poplar/mahogany, with maple rings: 9×13 tom, 16×18 floor tom, 14×22 bass drum; 5×14 400 snare with chrome finish.

Cymbals: Super Zyn, including 14″ hi-hats, 16″ and 18″ crashes or two 18″ crashes, 20″ or 22″ ride

MD: Over the course of many years with Sabbath, how do you see the evolution of your drumming?

Bill: Whether I’m writing a song or playing, I look for the best possible thing I can do as a drummer that will support the music. My drumming’s changed a lot. I think I became quite good. I hope that doesn’t sound egotistical. I became more confident. Going back to the late 1990s, early 2000s, when we were on tour, I was kicking ass. I was kicking absolute ass. I’d been practicing and playing a lot. And so, going through the Black Sabbath songs again was absolutely incredible. I was actually adding in new things because I’d forgotten how they were originally. So I started to rebuild them.

MD: Keeping it fresh is a skill in itself.

Bill: I can’t go onstage and play the same thing twice.

MD: Maybe that’s another jazz influence?

Bill: It could be. But I just can’t do it; I don’t have that kind of ability. I mean, I’m close to it: I know we take a break and play four beats. Yeah, I know that kind of stuff, but I’m always trying something different. Advertisement

We were trying to step out a little bit. When we did “Supertzar” [instrumental piece with wordless vocal choir from 1975’s Sabotage], I was very happy about that track even though it was very controversial. I’m glad that we went there just to go there. When I played drums and glockenspiel and added everything else to it, I felt really good with my parts. It made me work—think outside of the box.

I like that. I’m not very good at basic standard chops. I can’t play them anyway, truth be known: hit-hit-hit, that kind of stuff. I can’t play stuff I’ve heard before. Especially when I’ve heard other drummers playing it before.

MD: What’s happening with your two current bands?

Bill: Day of Errors was created in 2013 out of self-preservation. I had to; there was nowhere for me to go as a drummer. So I created my own band. We’ve got two records completed and a third one in the works. We just have to formally put them out and market them. Currently we have [vocalist] Dewey Bragg and Joey Amodea playing lead guitar. Advertisement

I love Day of Errors because I can play loud. I can be aggressive and be all the things that I was able to be in Black Sabbath. It won’t be the same as Black Sabbath, but it will be Day of Errors, and Day of Errors is unique.

And BWB [Bill Ward Band] is very healthy musically. We’ve been releasing singles on our own site. We’ve got at least another three albums right now to tour with. BWB is wide open. We basically have me and [guitarist] Keith Finch now, and we pull in a lot of guest artists that we like: bass players, drummers. We did that last year. We did a single as a dedication to the Las Vegas shooting massacre victims called “Arrows.” Brian Tichy came in and played drums. I knew that he would sound so good on that. I love doing that; I don’t have to be the guy in the middle of everything. I like being involved with other things as well, including writing or production.

When I did the final setup for Brian’s bass drum sound, I told him a story about the way that John Bonham and I used to get our bass drum sounds back in 1965. Back then, it was not unusual to be on the same gig with John. He would be in his band, and we were in our band. But we needed to listen to each other’s bass drum. So he would kick his bass drum and I would stand in front of it, about eight to ten feet slightly left, where it pinpointed. What we were looking for is a “sick feeling in the stomach.” He would say, “Are you sick yet?” I’d say, “Yeah, I’ve got it.” Then I would play my bass drum and he’d go, “No, I don’t have it yet…yup, you’re good.” We were sixteen-year-old kids—waiting for the punch in the gut. That’s how we measured the bass drum back then; we didn’t have f***’n microphones! Brian was laughing his ass off when I told him the story. But we used the same technique to get his bass drum sound. When you play loud, there’s a spot where that bass just pops right in. Advertisement

MD: So you go way back with Bonham, well before Sabbath?

Bill: In Birmingham, we always bumped into each other in the clubs. That was not unusual because there was such an unbelievable boom after the Beatles came out with “Love Me Do.” Everybody wanted to be in a band. Everybody was playing.

MD: Drummers were hanging out together and sharing?

Bill: There was a drummer named Mickey Evans who played with the BBC Light Jazz Orchestra. He also had a drum shop in Birmingham [Yardley’s]. We would all go there in the afternoon, and there was a plethora of people. Bev Bevan would be there, Bonham was there, Bob Lamb, Charlie Grima, Pete York would pop in. I think [Jim] Capaldi came in from time to time. We’d watch Mick play and he’d say, “I’ve got a new Purdie record!” He’d play it and try to play what Purdie was playing. He did a pretty good job, too. It’s just a beautiful memory: being in the shop, sharing, none of us had a nick of money or anything. And everybody was bright and sharp.

One of the drummers I was hanging with was named Brian Rubin. He was a jazz drummer for the Birmingham BBC Jazz Quartet. When I was a kid, thirteen or fourteen years old, I would walk into his drum shop and he would watch me. Then he’d sit down behind his snare drum and just roll out all this shit! I felt totally intimidated. And he’d say [gruffly], “Now listen to me. Don’t forget that! And I’ll tell you something else: give all of this away, share it. Don’t keep it to your f***’n self.” Talk about someone railing on you! But I didn’t know then that that kindred spirit between drummers existed. I feel blessed to have been a part of that Birmingham scene. Advertisement

Even today, that same thing exists. Tomorrow, I’m going to pop over to the NAMM show, and I’m sure I’m going to bump into drummers that I know. It’s the same scene: we share. I try to do that. I hope I’ve never been selfish with my chops or anything that I’ve learned—that I’ve passed it on. Especially with the students.

And I’d like to say something to students: the most important thing is to allow yourself to make mistakes. And try not to beat yourself up. If you’re going to beat yourself up over making a mistake or not being good enough, then don’t do it too long; because everything that you do as a percussionist is important. It’s not only important to you, but to other people. I encourage students to embrace who they are. I made all my mistakes. And I still make mistakes now. But my early mistakes were trying to be like somebody else, and being disappointed when I wasn’t like them: I had to be me. So I have to embrace me, and I have to see what “me” is capable of. And as long as I get out of the way of myself—then it all happens with the drums.