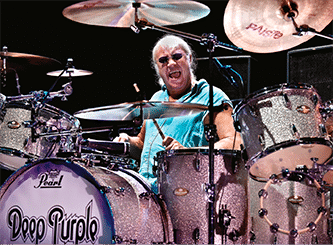

Deep Purple’s Ian Paice

Of all the remarkable rock drummers to have originated in the late 1960s/early 1970s, none was more astonishing than Ian Paice. If John Bonham was the zeppelin, Carl Palmer the tank, and Nick Mason the perpetual clock, Ian Paice was the attack jet, a supercharged amalgam of speed, technique, ingrained funk, and colossal swing. Paice’s blistering rolls could inspire a riot, his slamming 4/4 groove provided a rhythmic bed as wide as a football field, his bass drum playing and musical interpretation a revelation.

Of course, Paice made his name with the powerhouse British hard-rock quintet Deep Purple. Even today, Purple’s classic performances are astounding, built on Paice’s fury.

To go down the rabbit hole of Deep Purple’s classic albums is to glory in the genius of rock itself. Shades of Deep Purple (1968), Deep Purple in Rock (1970), Fireball (1971), Machine Head (1972), Who Do We Think We Are (1973), Burn (1974), Stormbringer (1974), Come Taste the Band (1975), and Perfect Strangers (1984) are a handful of their accomplishments. The albums contained such enduring songs as “Hush,” “Strange Kind of Woman,” “Highway Star,” “Smoke on the Water,” “Space Truckin’,” “Woman from Tokyo,” “You Fool No One,” and “Knocking at Your Back Door,” amid many more.

Deep Purple’s music established the cornerstone of the church of rock, the palace of grandiose excess and virtuosity, the great I AM of rock profundity, never to be repeated. And perhaps as impressive as the band’s past achievements is its enduring role as rock patriarchs still making vibrant recordings, inspiring large audiences young and old, and touring as if their life still depends on it. Advertisement

Now What?! (2013) and Infinite (2017) prefaced the band’s brand-new, twenty-first studio album, Whoosh! Far from grizzled granddads playing limp versions of their classics or writing bland new material, Paice, singer Ian Gillan, bassist Roger Glover, guitarist Steve Morse, and keyboardist Don Airey (who since 2002 have comprised Deep Purple’s “Mark VIII” lineup) continue to write songs of imagination and inspiration.

Simply put, Whoosh! maintains Deep Purple’s standards. Produced by veteran Bob Ezrin and recorded in Nashville, Whoosh! boasts vital, virtuosic, catchy, hardcore rock, without apology. Standout tracks include the deep dive of “No Need to Shout,” the menacing “Step by Step,” the prog-rock beauty of “Man Alive,” the 4/4 splendor of “And the Address” (a remake of the opening track from their debut album), and the cock-rocking “Throw My Bones.” Throughout, Ian Paice is a steamroller of rhythmic intent, an unceasing, unstoppable, nail-hard, deftly controlled pulse machine.

Whoosh! would seem to quell any rumors that Deep Purple has played their last notes as a rock band. Let’s find out what Ian Paice has to say about that….

MD: You have one of the most iconic and recognizable identities in rock music. There’s your incredible snare and bass drum technique, speed, and full-set mastery, as well as your open quarter-note hi-hat and fat 4/4 groove, which floats. It’s two ideas in opposition. How do you make it work? Advertisement

Ian: I’m playing big band music in a rock ’n’ roll context. That inherent swing and feel harkens back to those days. And I’m not saying it’s a good or a bad thing or a better thing, but in terms of rock ’n’ roll, it’s a unique thing. But it’s not intentional. It’s the way I hear things and the way I feel them. You can teach the technique of drumming to anybody, but everybody has their own personal, inherent feel of what a rhythm should be. Mine just happens to be that one. And luckily for me, a lot of people seem to like it.

The Secret to Relaxation

MD: Your drumming has always been very relaxed, which is one of the hardest things for any drummer to achieve.

Ian: I haven’t always been relaxed. I had a period in the late ’70s/early ’80s when I was in trouble. I realized that I was playing too hard. I was trying to be something I really wasn’t built to do, and I’d lost the feel and I was hitting harder than I should. The next time I got on the kit, I went back to playing comfortably again, playing within my physical limits, playing the things I knew would work, and it all came back.

The secret to relaxation is to remember you’re playing drums because it’s fun. The fact that it becomes your business or your life—that’s nothing to do with it. You start out playing because it’s fun. So why wouldn’t you be relaxed? Sitting comfortably is important, but playing to the limits of your body is also important. You are the way nature built you, and certain things you’ll find very easy and they’re the things you can do automatically, and then certain things take more work. So you must play to your strengths and understand what they are, and then you can be relaxed when you’re playing the drums. You’re not trying to go to a place that you’re not meant to be. Advertisement

MD: Regarding your beat placement or emphasis, is it ahead of the beat, dead center, or behind the beat?

Ian: Any great rhythmic feel is a combination of push and pull. My bass drum is on the beat, or maybe even slightly ahead, but my backbeat—the snare drum—is behind it. And it’s that magic combination of something that shouldn’t work that makes it happen. It’s a push-and-pull thing, and there’s an inherent tension in that.

The problem we have today as drummers is that nearly everything we do in the studio, especially in rock and very modern music, is all click-track determined. Now, you can love or hate click tracks, but they’re here to stay. The art is to make the click sound like you’re not playing to a click. You want to recreate that same idea of push and pull with the click track playing in your headphones, which is difficult. But once you find it, treat it as something you must deal with, then you’ll find a way of making it work. The click is all about precision; there’s no swing in it. It’s that absolute precision that gets inside your head and makes it work. But for those great feels, there must be a tension, and that to me is push and pull.

MD: Do you always play rimshots on the snare drum?

Ian: When I’m onstage, it’s mostly rimshots. A rimshot on the snare makes things obvious, especially when you’re on a big stage and it’s a loud outfit. We don’t use in-ear monitors; we have big monitors onstage. They give the impression of power onstage. I need to feel the guts coming from the stage, not just from above my head on the P.A. system. Advertisement

Tools of the Trade

Ian Paice plays Pearl Masters drums. His stage kit includes a 6.5×14 steel

signature snare, 8×10, 8×12, 9×13, 10×14, and 10×15 toms, 16×16 and

16×18 floor toms, and a 14×26 bass drum. In the studio he uses a 14×24

bass drum and removes the 10×14 and 10×15 toms. His Paiste live setup

includes 15″ Sound Edge hi-hats, 22″ and 24″ 2002 crashes, a 22″ 2002

ride, a 22″ 2002 China, and a 10″ 2002 splash; in the studio he takes

his crashes down in size and uses 20″ and 22″ models. His sticks are

Promark TX808LW signature hickory wood-tips, and his Remo heads

include Ambassador Coated snare and tom batters and Ambassador

Clear resonants, and a Powerstroke P3 bass drum batter.

MD: Do you also play rimshots on recordings?

Ian: Certain songs work better when it’s a sharp, hard backbeat. Other songs work better when you play off the middle of the head. One size does not fit all. Sometimes you can play quieter in the middle of the head, which gives a much bigger impression than slamming a rimshot. For each piece of music, you find the right solution.

Recording Whoosh!

MD: Whoosh! was recorded to a click?

Ian: Oh, yes. The speed of recording with the click enables you to do four or five takes, then combine them. What you hear on the album is an amalgamation of different takes because they’re all the same tempo. The click limits the drummer when it comes to playing left-field, crazy fills. That’s a little more difficult when you’ve got this metronomic track going on inside your headphones. Whereas when we had the freedom of tempo, if I played a drum fill that crept up a little bit, which is the nature of drum fills, as long as everybody else in the band felt it, everybody came in on the 1 even if the 1 wasn’t quite where it should have been. Advertisement

MD: How does Deep Purple record? As a band, as a rhythm section? Do you layer tracks?

Ian: We always start as a four-piece section playing together. In the studio we get some wonderful interaction. That feeling of being together is something that probably wouldn’t happen if you were layering it. Then you get another piece of music where the layering process is better for the music you’re trying to create. But generally we play and record altogether, and we separate the wheat from the chaff as we listen to it.

MD: There are great songs on Whoosh!: “Man Alive,” for instance. That Deep Purple is still making great records is unusual among legacy rock bands.

Ian: Most bands of our age and stature are quite happy living off past glories. But we’ve always been blessed with having great musicians in the band who are virtuosos. We couldn’t keep our sanity if we only played our music from between 1969 and 1973. What you hope to do is take enough of your hardcore fans with you, who understand that it can’t be the same—there’s no point in releasing a new record with another “Highway Star” on it. Over the last thirty years we’ve ensured that our fan base is catered to with material that sparks their interest. And when we go onstage it’s still a damn good band. If we blend new songs with more obscure songs surrounded by the well-known songs, everybody’s happy. We’re not just doing a nostalgia trip.

Paice on Pearl

MD: Do you play your Pearl drums in the studio, or a studio set?

Ian: I’ll use my kit if we can, but if not, Pearl provides what I ask for. With modern drums, if they’re good instruments, one kit will sound like another kit. A good drumkit is especially important, but people forget good drumheads are just as important. You get a great drum with a crappy head, it’ll sound like a crappy drum. Put a great head on a great drum, and you’ve got it cracked. Advertisement

MD: Tell me about your 6.5×14 signature snare drum.

Ian: It’s steel. Very rock ’n’ roll, immensely powerful, and has a lot of bass end to it. So I don’t need to detune to get depth. That’s what I use onstage. If there’s a sound I can’t get in the studio, I’m not averse to using another snare drum to get it done. The studio is an artificial situation; you’re not playing for people’s ears, but for recording gear. So sometimes you might need to change something.

MD: You use 22″ and 24″ crash cymbals, which are large.

Ian: They match the bigger drums, and I’m trying to create a big sound. I want the cymbals to ring. I want this lovely natural decay of an acoustic instrument. It’s like a bass drum. I don’t tune my bass drum for impact only. I swing somewhere between that and having a little duration on the notes. After the beater hits the head, you get decay as the head comes back to tension again. I like a blend of the two. I want it to go “bang!” with a note after it. It’s like when you play a snare drum. If you pull off quickly, the drum will sound different from how it does if you hold the stick on the head. It’s about the speed of release, and how you tune it. And the great thing with drums over any other instrument is there’s no guide to tuning. You have wonderful freedom with a drumkit.

The Paice Process

MD: How did “Man Alive” come about in the studio?

Ian: “Man Alive” began as a backing track. It was 90-percent cut live. We knew it back to front. We didn’t know what the song was going to be, because that’s not the way we create music. We present Ian Gillan with a set of musical pieces. He decides if he can make a song from it. We use our imagination when we’re playing these backing tracks of what we think the top line and the melodies and the lyrics will be, and that’s a weird thing when recording a piece. Most bands know what the song is. They know where the verse is going to be. We don’t. Advertisement

MD: You record the rhythm track first before you know the song?

Ian: Yes. We get everything we and Ian think is interesting. We do it back to front; that’s the way we’ve always done it.

MD: What’s making that clock-like tick-tock sound?

Ian: That was a rimshot, just dry-sticking on the rim, and Bob Ezrin fooled around with the EQ so it sounds like a clock.

MD: How did you create your part there?

Ian: We started that song back in 2015, but we never finished it. We knew it had to be spacey and ethereal because of the nature of the main riff. Ian was already writing stuff down. So we just kept on with this blend of ethereal, spacey stuff going into the verse. We had no idea where Ian was going with this, but he was confident. So when we heard the master back, it was as much a revelation and a mystery to us. We could have been anybody else hearing it for the first time.

MD: With that in mind, how do you generally create a drum part?

Ian: I take the mood of the music and imagine where the lyrics and the top line will be. If you’ve got a dirty blues, it won’t be matched to happy lyrics. And if you’ve got a rock ’n’ roll, smashing-your-head track, it’s not going to be a dismal sad lyric. We have a ballpark idea of what’s going to happen. We work off emotion.

MD: On the surface, “Step by Step” sounds like a 3/4 time signature.

Ian: It’s 3/4 but it breaks out of 3/4 occasionally. When these things are being created, they might want to drop a beat or add a beat. It’s up to me to work out the best way of approaching it to keep it rolling without losing the groove. Because the easiest thing to do when you’re mucking around with time signatures is to lose the feel. So, as they create a time signature, I try to lock into the lyrical content of that riff. What will make that riff flow the best, especially if it’s not in 4/4? Sometimes they’ll give you a riff in 3/4 and it’s better to play 4/4 against it. But it depends where the accent of the 3 is placed. If you put it in the wrong place, it makes the song feel jumpy, but if you put it in the right place, people won’t even notice it. They’re still tapping their foot as if it were in 4/4 time. Advertisement

“I had a period in the late ’70s/early ’80s when I was in trouble. I’d lost the feel and I was hitting harder than I should. The next time I got on the kit, I went back to playing within my physical limits, and it all came back.”

MD: It’s great that Deep Purple is essentially a workshop.

Ian: That’s what we do. We still love doing it, and we still see a future. We also understand that the clock is ticking every day you get up. And that the future is not as long as it used to be. We all still have the ability and the desire and the love to keep playing, keep looking forward, and keep trying to do it, because one day very soon we won’t be able to.

MD: The songs “And the Address” and “Dancing in My Sleep” contain what I think of as your classic fills and feel: that slamming, open hi-hat trademark. How did you create drum parts for those songs? Advertisement

Ian: I think every musician has a fallback point. That means you either can’t find anything else to play or it doesn’t need anything else. You don’t need to look for solution B. But when we began the album, it felt like it may be the last time we record a new album. Bob Ezrin suggested since the first Deep Purple album started with “And the Address,” why not include it on Whoosh! It would complete the circle. But I’ve got to be honest: I don’t think anybody’s really thinking that this may be the last record. We have so much fun. I’m not sure there’ll be another record, but never say never. Making a record is easy, man. Coming up with ideas, that’s the hard thing to do. Anybody can sing an Elton John song, but not everybody can write or create an Elton John song.

MD: Is finding success today similar to the way Deep Purple found success? What do you say to young musicians?

Ian: You must approach it the same way we did. You’re doing something with your pals because you’re having fun. That’s the only reason that kids get together and form a band, because they’re having fun. The concept of it becoming something more, you can’t worry about that. We didn’t. But there seems to be a whole generational thing against live music now. People are watching their music, not listening to it. And where are the new virtuosos? The idea of taking a solo is alien, so that’s different today.

If you go chasing success, you’re probably not going to get it. Success is one of those things where you walk along the street and it taps you on the shoulder. It’s crept up behind you and there it is. If you go chasing it, you’ll never be able to run fast enough. Advertisement

Story by Ken Micallef

Top and middle photos by Andrew Clowater, bottom shot by Bob Mussell