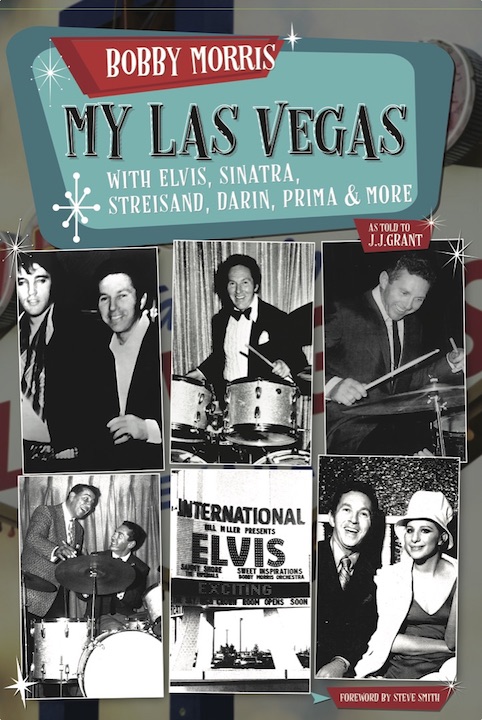

Bobby Morris’s My Las Vegas—With Elvis, Sinatra, Streisand, Darin, Prima & More

From the Bronx to the Borscht Belt to Vegas, he saw it all on his way to the top.

The next time you look back on a gig in anguish because the monitors weren’t great, or your kick drum was creeping, or you clammed a couple of fills, just remember, it could’ve been worse. At least you didn’t have a dead body thrown in your direction.

Bobby Morris actually experienced this extreme job hazard as a young drummer trying to make a name for himself on New York City’s big band circuit in the 1950s. As he writes in his new memoir, My Las Vegas—With Elvis, Sinatra, Streisand, Darin, Prima & More, the incident happened during the second night of a two-night engagement at a rough joint in the Bronx appropriately called the Bucket of Blood. Morris says everything went fi ne the first night. Midway through the second gig, however, a huge brawl broke out. A loud bang followed; Morris assumed it was a gunshot. Then said dead body went flying through the air. So what was the young drummer’s first thought upon seeing a lifeless body headed in his vicinity?

“It was duck,” Morris remembers with a laugh. “As quickly as I could, I got right the hell out of there.

“After the body was thrown at me, I ran out the back door and never looked back. Fortunately the drums belonged to the club. I just took my sticks and it was ‘Bye!’ I didn’t care about getting paid or anything.” Advertisement

Morris says once you’ve been put in that type of predicament on the bandstand, you can pretty much handle any situation, from being tapped to sub with Frank Sinatra at a moment’s notice, to helping Elvis make his live comeback as both drummer and conductor, or starting a booking and management company from the ground up—just a few of the more notable entries in his mindboggling resume.

“It helps you develop an unflappability,” Morris explains. “And you need that in this business. It’s like going through bootcamp.”

As a Polish immigrant who arrived at Ellis Island during the Great Depression at age ten without knowing a word of English, Morris knew about tough gigs. He endured a long, hard slog to the top of his profession. Before he was working his way up from the Catskills to Vegas as a drummer, he shined shoes, mowed lawns, delivered newspapers before dawn, worked in factories, and served sandwiches down at the docks, practicing the rudiments he was learning from the legendary Henry Adler on the countertops.

“As soon as I came over, I realized, you’ve got to work,” Morris says. “So I did whatever I could to help out my family.”

After ditching school to watch Gene Krupa play with Benny Goodman— for twenty-five cents!—drumming became an all-consuming endeavor for the young Boruch Moishe. (Morris legally changed his name once he started playing professionally.) When he wasn’t stringing side hustles together to bring home money for his family, he worked tirelessly on his drumming, a pursuit his father viewed as frivolous. Advertisement

“Right before I started working in the Catskills, my father said, ‘What are you practicing so hard for, five or six hours a day on that drum pad?,’ Morris recalls. “He said, ‘Nothing is going to happen. You’re not going to amount to anything.’ Well, I did amount to something.”

Morris hilariously recounts in the book how his father got to experience that his son did amount to something. After a show with Eddie Fisher at the Waldorf Astoria in the ’60s, his father not only got to see Morris play to a packed house behind one of the most popular entertainers of the day, he also witnessed him getting paid for the week.

“It was $1,500 in cash—very good money for those days,” Morris recalls. “My father thought I robbed a bank! I said, ‘This is what I get paid, dad.’ He said, in his broken English, ‘Wow, that’s vonderful!’” Advertisement

Morris isn’t hustling so much these days. He splits his time between Las Vegas, Utah, and Florida, booking acts here and there and doing the occasional drum clinic, imparting the lessons he’s learned from so many years in the business. “I’ve been trying to help out young musicians and young drummers,” Morris says. “I try to give them instructions on behavior and how to network and how to practice hard and work hard. I tell them you can’t give up. I didn’t, and look what happened for me.”