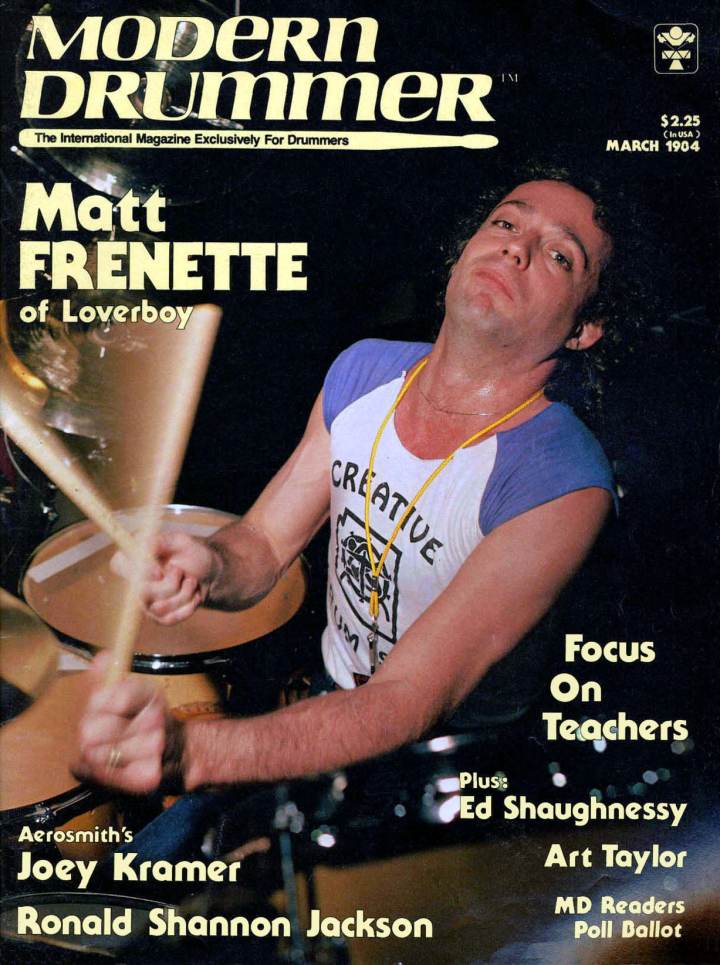

Joey Kramer — Finding A Place In The ’80s

Talk about the best American hard rock bands of the ’70s and Aerosmith has to be mentioned in the first breath. Driven by a sound that was as intense as it was relentless, Aerosmith initially caught the attention of the rock press not because of their music, but because of the remarkable look-alike qualities of lead vocalist Steven Tyler with Rolling Stone Mick Jogger. The critics pressed a bit further and came up with another Rolling Stones comparison—guitarist Joe Perry with Keith Richards.

For some time afterwards it was all uphill for Aerosmith, as the band desperately tried to shake off the Rolling Stone albatross that journalists strung around their necks. Few denied Aerosmith’s rock ‘n’ roll capabilities, but the band’s image problem stifled their progress. The early LPs were solid enough—Aerosmith and Get Your Wings helped define the direction ’70s hard rock would take. But still Aerosmith floundered.

It was the seemingly incessant touring that finally broke the band. Aerosmith became a road band in the purest sense of the term. And it was in the clubs and concert halls across America that the band perfected its rock ‘n’ roll power and energetic delivery. By the time albums like Toys In The Attic, Rocks, and Draw The Line hit the record shelves, Aerosmith had effectively silenced the cries of “Rolling Stone rip-offs. “Aerosmith had created a niche in the rock hierarchy the only way it could: the HARD way. Advertisement

Nailing down the beat for the band is Joey Kramer. Not as verbal or provocative as Steven Tyler or other members of the band, Kramer nevertheless steadily built a reputation as one of hard rock’s most efficient—and physical—drummers. On stage his powerful drumming sets the pace for Aerosmith; in the studio he is responsible for the full bottom sound the band always seems to have.

RS: It seems as if Aerosmith has kept a particularly low profile in the ’80s thus far. Ever since Steven Tyler got hurt while riding his motorcycle in 1979, the band hasn’t been as active as it once was.

JK: Yeah, that’s very true. But believe me, it’s not like we didn’t welcome the rest. I mean, we had been on the road for a long, long time; years and years of tours, and running from one show to the next. It was very hectic and trying. We all had vacation homes and families, but we were always on the road. So it got to be that any little thing that gave us some time off was pretty much welcomed. That’s not to say, of course, that Steven’s accident was welcomed. But when it did happen, it gave the band an excuse to take time off. Besides, musically we were in a rather dormant state where nothing much was happening. Advertisement

RS: What did you do with your time off?

JK: Well, I had built a house up in the woods in New Hampshire and I just wanted to go there and stay there. I didn’t want to know about looking at my drums. I didn’t want to know about being in the city or dealing with people. I’d had it with the music business for a while. I just wanted to spend some time with my wife and kids. I also had other interests besides music that I wanted to pursue.

RS: Like what?

JK: Well, I’m pretty heavy into sports cars. And, of course, my family; I have a son and that was the first time I’d had a chance to spend time with him since he was born. Now he knows he’s got a dad. I’ll tell you, I’ve come to realize how important that family thing can be. It contributes to my playing and my confidence. It’s great to know that there’s someone behind me all the time. I’m really grateful for what I have.

RS: For a long time in the 1970s, Aerosmith set the pace for American hard rock bands. Now that we’re in the ’80s and the music has shifted to a more techno-rock direction, how does the band intend to fit into the scheme of things? Advertisement

JK: Well, I think rock ‘n’ roll, the way it used to be played, is starting to come back a little. It may not come back to what Aerosmith was doing in the mid-’70s, but the feeling of that type of rock is coming back. We realize that the music has changed and we’re trying to change with the times. Sometimes it’s difficult listening to the music on the radio today; there’s a lot of good stuff, but there’s also a lot of trash. The one group I have to admire is the Stones because they’ve transcended all the fads and changes in rock. That’s what puts them in a class by themselves. But in terms of Aerosmith, we realize we’re coming from an entirely different thing. There aren’t many bands like Aerosmith that are really happening now. But I have confidence we’ll be able to find a place in ’80s rock ‘n’ roll. Good basic music that moves people is always in demand.

RS: As the band’s one and only drummer, what have you done, drum-wise, to contribute to the Aerosmith sound?

JK: Well, our music is basically simple, so I try to keep things as simple as they need to be. Today a lot of drummers forget what a drummer’s role in a band actually is. For instance, what Charlie Watts does and what Ringo did and what John Bonham did was great. Bonham was one of my very favorite drummers; he played in such a way that he had outstanding style, yet he managed to keep things simple when it was necessary to keep things simple. A lot of what was involved in his playing—and my playing, so I like to think—is more feeling and emotion, as opposed to technical genius.

RS: I take it that you didn’t take many drum lessons as a kid.

JK: No, I really didn’t. I’m completely self-taught. I guess I started playing when I was 14 years old. And I don’t read music; I play strictly by feeling.

RS: Most drummers who don’t read music bring up the concept of “feeling” when they’re talking drums.

JK: When we first started the band, I was enrolled at Berklee in Boston and had attended classes for about three weeks, I guess, until it got to the point where I realized it was hurting me rather than helping. Getting into that angle of drum playing was suddenly turning into a negative source as far as the direction I wanted to go in. I was playing matched grip because I was self-taught, and at the school they wanted me to play conventional grip. Also, I wanted to take lessons on the vibes because I had always wanted to play the vibes. Well, they wouldn’t let me do i t . Nothing really worked out for me at Berklee, so I left. It was probably the best move I ever made. Advertisement

RS: So you base your entire drum style on feeling.

JK: That’s right. There are a lot of drummers out there doing studio work who can fit into any situation and sound just the way the producer or whoever wants them to sound. But at the same time, they don’t sit behind their kits and make one particular band happen. However, with drummers like Bonzo or Charlie Watts, you can sit back, listen and just soak up the feeling. That’s what made Led Zeppelin happen, and after 20 years, it still makes the Stones happen.

RS: What kinds of bands did you play with before Aerosmith?

JK: I played with a lot of black bands. Those cats taught me a lot about playing with feeling. I remember playing in a ten-piece group that included four singers out in front. I used to go to rehearsals with just the singers, so I had to learn to accent all their choreography. That was real interesting and real helpful to me as a rock drummer later on.

RS: Did you return home to Yonkers, New York, after you quit Berklee, or did you move right into Aerosmith?

JK: Well, I had been in Boston in 1970 to go to college, but that didn’t work out either. I had gotten real sick with hepatitis and mono in the winter of 1970, so I had to go home. I was sick in bed until the end of that following summer. That September I decided I wanted to go to Berklee, so I went back to Boston, stayed at Berklee for about three weeks, and then bumped into Joe Perry and Tom Hamilton. They were trying to start a band with Steven. The funny thing is, I had already known Steven—we went to high school together—but Joe and Tom didn’t know that. Advertisement

RS: It sounds like Aerosmith was initially a big coincidence.

JK: Yeah. You see, there was a friend of mine from back home in Yonkers who was also a friend of Steven’s. He was going to start the band with Steven, Joe and Tom. But when I spoke with him in Boston, he told me he didn’t have the time anymore to do it. So he said he would turn me on to the guys, since I was a drummer and they’d be looking for one. I was looking for a gig at the time so it was perfect. That’s how the whole thing started.

RS: Were your intentions always to be a drummer?

JK: Yeah. I think it came from my rebelling as a kid growing up in the 1960s.

RS: In what ways were you rebellious?

JK: When I was in junior high school and playing in bands, my parents were always holding everything over my head. They thought music—particularly drums—was nice as a hobby and perhaps a way to earn some money on weekends, but that was it. Until the time I left home, my parents wouldn’t let me grow my hair long. I guess that’s part of the reason why I’m 33 years old and my hair is still long. But when you’re 14 or 15 nobody is interested in listening to you. When everyone at my high school—which, by the way, was a college preparatory high school—was explaining at graduation what universities they’d be attending and what courses they were going to take, I only wanted to talk about joining a rock ‘n’ roll band. All I knew was that playing music and playing the drums made me feel a special way, so why should I give it up? Everybody was against my playing the drums, but the more they told me that, the more I wanted to get behind my kit. Whenever I played I was happy. That’s all I knew or cared about.

RS: How would you compare the difficulties of being a young drummer today to what you went through in the late ’60s?

JK: Young drummers today send me tapes of their bands and ask for advice, but they have no interest in what was involved in making it or what it took to get there. They just see what they see and that’s what they want—right now. They say, “Wow, what a life!” Well, what they don’t know, and don’t care to know, is that sometimes it sucks. When we first put the band together, we spent two-and-a-half years all living in a four-room apartment eating brown rice and carrots. Nobody’s interested in that, so I never mention it. But young drummers have to realize that whatever you put into your drumming and your band is what you’re going to get out of them. Impatience seems to be the end result of the music scene today. Advertisement

RS: As a kid, did you hang out much in New York City?

JK: Oh yeah. I used to go to the Fillmore a lot. I’d catch Procol Harum with B.J. Wilson, and all the other great bands and drummers. That’s where I became inspired to be a drummer. Guys like John Bonham had a big influence on me. I had a great admiration for him.

RS: Was he your biggest influence?

JK: Yeah. Steven actually turned me on to him. He was into Zeppelin when I first joined the band. At the time, I was into Clive Bunker and Mitch Mitchell and that sort of style. Then Steven turned me on to Bonham and I just zeroed in on him so heavily because of the way he made the whole band feel. His role was big enough that, when he died, Led Zeppelin wasn’t able to carry on. Now people realize how big a part he played in Zeppelin’s success.

RS: I heard that Bonham’s former roadie became your roadie. Is that true?

JK: Yeah. Henry Smith was Bonzo’s roadie for two-and-a-half years before he began working with me. He was my roadie for about three years. Henry turned me on to a lot of the tricks Bonham used to do, as well as a lot of his playing technique. I learned so much from him and Steven. There are so very few drummers around like Bonham today. Today you hear very little from drummers like Ginger Baker or Aynsley Dunbar. Advertisement

RS: I heard some of Ginger Baker’s music while I was in England a couple of months ago. He’s back playing with a trio.

JK: Trios are great for drummers because you have so much more room to breathe. For instance, when you’re going around the kit to play a fill or something, in a trio, that’s the only thing happening. There’s no keyboards or rhythm guitar; there’s nothing filling in. So everything you play is outstanding. A lot of times I’d like to be able to do that, but what being a drummer is really all about is being able to adapt to the type of band you’re playing with and making that band happen. Nobody is interested in how busy you can be or how good your chops are. It’s how the band feels and comes across that’s important. There are a lot of drummers who can play circles and rings around me as far as solos go. But I’m right for Aerosmith, and that’s all that really matters to me.

RS: What would you say is the one Aerosmith song that best typifies your style of drumming?

JK: It’s a song off the Rocks album called “Nobody’s Fault,” which was never a popular Aerosmith song. We never even did the song live. But we had a whole lot of fun recording it, because we did it at a warehouse that we used to have up in Boston. We brought the mobile truck in and just set everything up. It represents some of my best drumming with Aerosmith, because not only was the playing real good, but the drum sounds were probably the best I ever got. It’s hard, though, to pick one song or one instance, because I’m never really satisfied with the way I play. I’m to the point now where, as I grow older and mature a little bit more, I might allow myself to be a little more satisfied with what I do behind the kit. But it’s only on a temporary basis.

RS: I think that when drummers, or for that matter any musicians, say they are completely satisfied with their performance, that’s the first indication of a lack of growth. More times than not, what you’ll hear from those artists will be stagnant. Advertisement

JK: I agree. That’s when they should hang it up and put down the sticks. Recording with Aerosmith, though, has been one challenge after another. There would be times when we’d go into preproduction, and we’d rehearse a song for maybe three or four weeks. I’d be playing a certain figure for that particular song, and after doing it over and over again, it would feel good. But then the guys in the band would come up to me and say, “Well, it doesn’t wash anymore. Now we want to try this.” So I’d sit and listen to the figure, and I’d say, “No man, what I’m playing now is much better.” But they’d insist I try something else to go along with the new arrangement. I’d usually be open-minded enough to try something else. So I’d go off in some room with a tape, and try to come up with a new figure, apply it to the song and try to make it sound as comfortable as the figure I had been playing.

RS: It must be quite frustrating at times.

JK: It is, but it makes me a more flexible musician. I’ll tell you though, nine out of ten times it goes full circle and I wind up recording the thing I originally played. And everyone else usually agrees on it. But, in the process, there’s a whole lot of stuff I’ve learned and filed in my mental catalog that maybe I can use later on. A lot of drummers acquire an attitude when other people in the band say, “I think you should play this.” They get defensive, like, “Hey, wait a minute! I’m the drummer. Don’t tell me what to play.” That’s not what it’s all about, because a lot of times somebody from the band can hear something that you can’t. It really helps. You’re the drummer and you’ll ultimately be playing the part. But whatever it is that makes the song and the band work is what should be recorded. It doesn’t matter who comes up with i t .

RS: It’s great to know that you’re open to outside comments and advice. A lot of musicians aren’t.

JK: I’m open to comments, and I’ll try what other members in the band have to say about a particular song, or part of a song. The only way to judge it is to play these suggestions, and then listen to it back. I’m not afraid to admit it if what I’m playing is wrong and what someone else has suggested is better. But when somebody criticizes what I’m playing, I’ll say, “Okay, that’s fine. Do you know a way to play it better? If you don’t, keep your words to yourself.” Advertisement

RS: Steven Tyler is an ex-drummer. Do you have a special relation ship with him because of that?

JK: Yeah. I have to give Steven a lot of credit because he had a lot to do with the style that I picked up when we started as a band. He turned me on to a lot of things. At the time we began I wasn’t interested in playing all that simple, because I never knew what it was like to fall into a pocket and make the band cook. Steven made me realize that I was the one who was responsible for making the band feel right. I’d go to rehearsals and practice just with my feet one day, and just my hands the next. Steven turned me on to his style until I picked up on it and advanced it, and ultimately took it over myself. Steven and I have a pretty good relationship because of this.

RS: Do you work off each other in the studio?

JK: Steven is very astute and tuned in to the drums. So when we go into the studio to work, I depend on his ear a lot. I depend on it when we play live as well. For instance, during soundcheck I’ll rely on him to go out and work with the soundman to get the sound that he knows I want out of my drums. And when we’re in the studio, he’ll do the same with the engineer. Steven is simply tuned into the same things I like in a drum sound. On the song that we were just talking about, “Nobody’s Fault,” the bass drum pattern is so simple. It’s just a one-shot note and it’s real wide open. Steven took the bass drum and made it sound like a house, so every time I hit it, it was like, BOOM! And the figure on top was real busy. The strange thing is that I wasn’t even there when he did that. But he knew that, since it was so wide open, he had the space to make it sound the way it did. And when I heard it, I thought it was just great. Today I use those same ideas on stage to make my bass drum sound pretty much the same way.

RS: How do you get your bass drum sound on stage?

JK: It’s something nobody else really uses because you need to do a lot of work with your foot. But on stage I have a big monitor system behind me which a lot of people think is for vocals. The only thing that comes through those monitors is my kick drum. They mike the bass drum for the P.A. right off the drum itself. But these monitors allow the rest of the guys in the band to hear it. Many times, guitarists, keyboard players and vocalists hear their drummer’s kick drum, but it’s flat and sounds like cardboard. With the monitors I get a real deep “thud” that you can feel in your gut. On stage it really fills things out and rounds out the bottom of the band. It’s been great. Drummers come up to me all the time and ask how I get my bass drum to sound like that. It took a long time to get the details right. Advertisement

RS: Did Steven Tyler ever play drums on any Aerosmith records?

JK: Yeah, as a matter of fact he did.

RS: What songs did he play on?

JK: All I can say is that he did, because you asked. To tell you the truth, he didn’t even take credit for it on the record. I don’t really want to get into this, but it was a song I was very much opposed to. So I said, “Look, if you want to do it, do it yourself.” And that’s exactly what he did. It really sounds like it. I don’t even have to mention the song. People who know my playing will be able to pick it out right away.

RS: You and the other members of the band like to consider Aerosmith a touring band. Judging by the number of shows the band did in the ’70s, I’d say that was a pretty accurate description. How do you make your drumming sound fresh and exciting night after night?

JK: So much of our show is the spontaneous excitement that’s coming off the stage, and a lot of that I bounce off the audience. There’s a point in the show where I do a ten- or twelve-minute spot by myself. My drum riser is motorized and on wheels. It puts me out in the front of the stage where a huge circle of lights comes over me while I do my drum solo. The way you can make your drums sound fresh and exciting is really surprisingly easy. As long as the band is playing well, that’s pretty much all it takes. Halfway through the first song I can tell pretty much how the show is going to go. If it’s right, my drum playing is right; if something is weak, then I take it upon myself to change it and make it right. I kind of play the mother hen role in the band, because as soon as anything goes wrong, everybody looks to me to fix it. Somebody once told me that the drummer in the band is the heartbeat, the bass player is the blood, and everyone else, the extremities. Advertisement

RS: That’s an interesting way of looking at it. And of course if the blood doesn’t pump through the heart the right way, it’s just not happening.

JK: That’s right.

RS: Do the drums still mean the same thing to you as they did when you were a rebellious young kid?

JK: I still enjoy the drums very much, and I enjoy playing the way I play because I love the physical aspect of it. I like to perform as well as play. Most drummers either go one way or another—they perform or they just play. I like to incorporate both, which, by the way, took me a long time to do. It’s not an easy thing to do. But eventually you find that you perfect the combination enough so that you have a good time doing it. And as long as you have a good time doing it, everyone else in the band and in the audience gets off on it too. It’s not the kind of thing where you say to yourself, “Gee, I hope everybody is picking up on it.” You don’t have to cram it down their throats.

RS: Few drummers do extended solos in concert anymore. Do you consider a solo an important element?

JK: As far as soloing goes, I don’t consider myself an outstanding soloist, but what I do is take the best of what I can do and take advantage of it. And yeah, I think it’s important because of the reaction I get from the people listening. I may be sitting behind my kit doing something fairly simple, but I have the ability to put it across to the audience in such a way that they really get off on it. It’s the audience that we’re playing for. Those are the people who really count. They buy the albums and the concert tickets. They’re the ones who support the band. I do a little thing at the end of the solo where I play with just my hands. The people love it; they go nuts. That’s the highlight of the solo.

RS: Where did you get the idea to include that in the solo?

JK: In truth, it’s one of the things Bonzo used to do. He always amazed me whenever I saw him do it because he’d get his hands going so fast. I could never understand how it was humanly possible. Then I would listen back to my version after I had done it in a show, and I’d hear the same thing I heard with Bonzo. That’s a great feeling. Advertisement

RS: How have your drum sound and style of playing matured over the years?

JK: Well, when I first came into Aerosmith I was a very busy drummer, but what was called for within the context of the music was a more simple approach. When we did Aerosmith, our first album way back in 1972, it was the first time I’d ever been in a recording studio. We set up all our gear in this studio where they used to do television commercials. Then we played the songs once or twice live, with microphones set up in front of the amplifiers and the drums, and that was it. That’s how we did the first LP—live in the studio.

RS: Did being in the studio for the very first time intimidate you or overwhelm you?

JK: Yeah, it did—it really did. For the first album and partially through Get Your Wings, our second, I really didn’t have a handle on getting things just right. I definitely found it a lot more difficult than playing live. For one thing, I didn’t like being in such a confined area. That took a lot of getting used to. On stage I felt free. There’s a lot more space around me.

RS: What other problems did you encounter in the studio?

JK: I had problems with my timekeeping, because I was so conscious and aware that everything had to be picture perfect. Finally, it got to the point where we all realized that it can’t be like that. We used to go for tracks and do them over and over and over again until everything was perfect. But it took a long time. Advertisement

RS: Do you think that when you do tracks like you described it—”over and over and over again”—you make records instead of music?

JK: Yeah, that’s a good way of putting it. But back then everybody else in the band was in the same situation I was in; no one had any studio experience except for Steven, and even he didn’t have much. But yeah, that was pretty much the case. We didn’t know any better. We figured that you had to do it again and again, because that’s the way you got the song to sound better and better. Now I’ll go in the studio and do a song with Steven, Tom and Jimmy [Crespo] and do two, or maybe three takes’ of a song. If it doesn’t happen the way it should, we’ll go on to something else. After the second or third take, it starts to go downhill. I like to go in, do the song and get as much spontaneity out of it as I can. A lot of times you can get a song picture perfect, but the feeling isn’t there. Then what good is it?

RS: What do you do to keep in shape when you’re off the road?

JK: I run and I work out at the gym. One of our security guys is a real close friend of mine. He takes me to the gym and tortures me three or four times a week.

RS: Do you practice when you’re not touring or recording?

JK: No. When Aerosmith isn’t touring or recording I rarely look at my drums, unless it gets to the point where the band is off for some ridiculous amount of time. Usually after I get done with a tour, I don’t do anything for two or three weeks. Then after that, the band usually starts to rehearse again. Sometimes we’ll rehearse two days a week just to keep in touch. I find that such a large part of my drum playing is physical that I just have to keep on top of my endurance and keep myself in shape. As far as the chops go, after we do three or four shows, it all pretty much comes back.

RS: Do you do much session work?

JK: I haven’t done much recently, but I just moved back to New York and I’m ready to do more session work since I’m closer to the recording scene now. I want to play with different people and get my name around more than it presently is. Advertisement

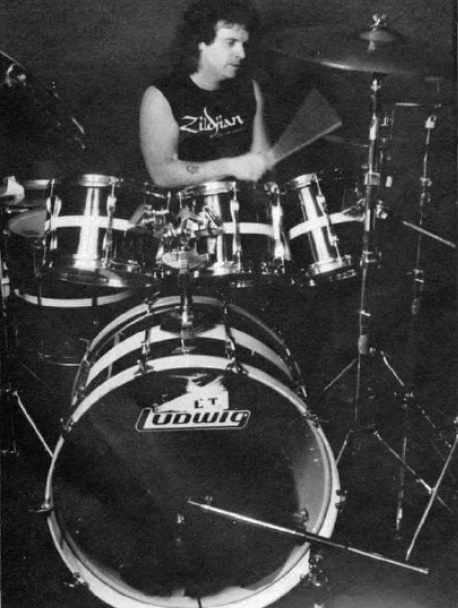

RS: What kind of kit are you playing these days?

JK: I’m still using Ludwig drums, which I’ve endorsed now for the last seven or eight years. I’ve used basically the same set for a long, long time. I use three rack toms and two floor toms. The rack toms are 8″, 10″ and 12″ across the top—power toms. I use all Zildjian cymbals. The rest of the kit is pretty standard.

RS: Drummers hate to be told that they’re overplaying their instruments and getting in the way of the music. How do you make certain you don’t overplay your drums?

JK: When the band isn’t happening, it could very well be because the drummer is playing too much. I’m very conscious of not overplaying because that’s the kind of thing that can kill the sound of my band. It’s not what’s called for in Aerosmith. Aerosmith is definitely a guitar-oriented band. So what I need to do is keep good, solid time for the most part. When I do put in a little more, I try to make sure I put it in the right places. You can be a busy drummer and not overplay, as long as what you play needs to be played and you play it in the right spot.

RS: So many of the new bands today are using drum machines. Does that bother you?

JK: Yeah, but only because much of what they’re getting out of the machine is very sterile sounding.

RS: Have you ever used one?

JK: Yeah. I use it occasionally to practice with. I’ll stick it through an amp and headphones, and use it as a click track. I’ll play along with it or around it as if another drummer is there with me keeping time. But I never use it when we record. Advertisement

RS: You mentioned before that you’d like to begin playing with other musicians in addition to those who make up Aerosmith. Does that come from a need to broaden your musical horizons, so to speak?

JK: My first and foremost allegiance will always be to Aerosmith. The band has always been my first love. However, as a drummer and musician, I’m ready to spread myself out a little bit more and work with different musicians whenever I have the time. I just want to be recognized by my peers as a drummer who does his job. I ‘m not really interested in being a rock star. I just like to be known as a real good, solid drummer. I truly enjoy what I do. I work hard and get a lot of gratification out of it.

RS: How would you feel if your son turned out to be a drummer in a rock ‘n’ roll band?

JK: He already is a drummer! He’s two years old and that’s all he can think about. He’s got this thing for Animal, the drummer in the Muppets. The funny thing is, I never encouraged him at all, although I have to say that I had a little kit made for him after he showed interest in the drums. He’s just banging things all the time. I guess he’s on his way to becoming a drumming fool, just like his old man. Advertisement