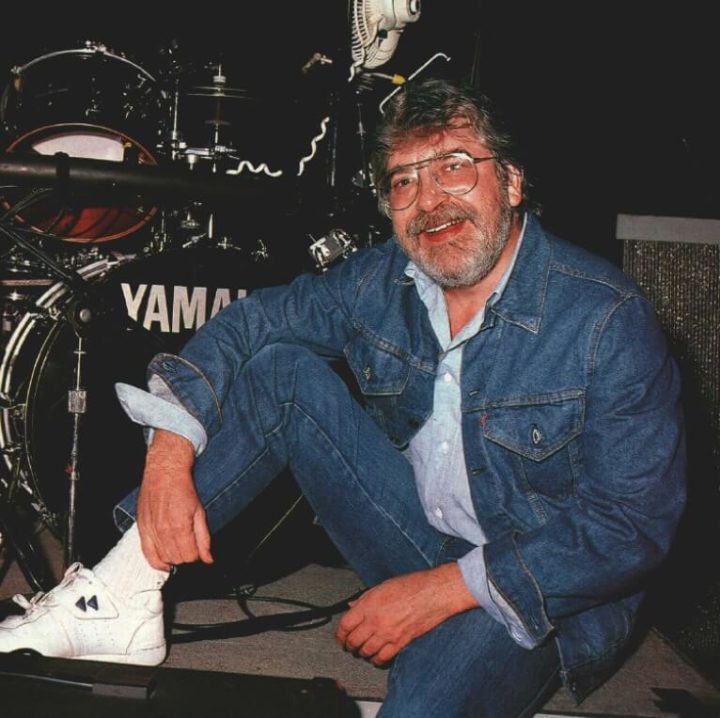

The Moody Blue’s Graem Edge

So much of Graeme Edge is tied up in having been a member of the Moody Blues for the past 22 years. I knew that, if I played a game I call album association with Graeme, I would end up with an outline of him. The game is like word association, but with albums instead of words. I asked him to share what came to mind at the mention of each of the Moody Blues albums.

Days Of Future Passed: “That was dear old [producer] Peter Knight, back in the studio.”

In Search Of The Lost Chord: “Very exciting—first time we were allowed into a studio completely on our own. It was exciting and a little bit scary.”

On The Threshold Of A Dream: “Proud—one of my favorite albums. It’s where we really started to come of age, gain confidence, and really take some risks recording”

To Our Children’s Children’s Children: “Landing on the moon. That was in that period of time, which was very exciting. It was a feeling of being in history. We used to think of it—God, the conceit of it—as the record to put under the foundation stone of some building, because that’s what it says on the top: ‘to our children’s children’s children.'”

A Question Of Balance: “That was the start of where we were almost treated as semi-deities, and we very much wanted to reflect what the title says: that maintaining yourself is a question of balance. It’s very hard to maintain your equilibrium under those pressures.” Advertisement

Every Good Boy Deserves Favour: “I’m proud of it, but it wasn’t a milestone.”

Seventh Sojourn: “That was when we had come to realize that we were running out of inspiration. The cover looks like a desert. When you open it up, everything is completely brown except for one tiny green leaf. There was still life and hope; the band was still alive, but that’s how we felt.”

Octave: “That’s just full of pain. Poor [producer] Tony Clarke was going through such agonies, and losing Mike Pinder was hard. He was a very talented man before he believed his own press. A great, great guy—a great asset.”

Long Distance Voyager: “Relief—total, complete relief. It was working. I was happy; the thing I wanted to do more than anything else in my life was back on track. It was happy—joy.”

The Present: “It was a bad time for me personally, because I was going through a breakup. All of us were in a funny state. If you listen to that record, each song individually is fine, but every one of them is a downer.” Advertisement

The current album, The Other Side Of Life: “Pleased as punch. We used a new producer, Tony Visconti, who is great to work with, and we developed a whole new set of morals in the recording studio. We used to own our own studio and have free studio time, and because of that, we got really sloppy. If we said we’d get to the studio at 11:00, people would file in between 11:00 and 12:15, and then we’d sit down and have a cup of coffee. Tony Visconti is a producer, and we start at 11:00—no breaks. We work through until 7:00. We get more done in those eight hours than we used to in 15, because the adrenaline runs and the excitement is there. Now there are so many ideas sparking. It keeps us up; it keeps us driving.”

Driving indeed—for nearly a quarter of a century with some of the most unique and courageous music during the most exciting times of rock ‘n’ roll history. The Moodies were (and still are) technologically advanced for the times—any times—and because of that, in those early days, their music was sometimes construed as pretentious. Mostly it was because they cared so much about it—the unadulterated courage and an uncompromising integrity. And it was that integrity that accounted for the creative output, the refusal to conform, and even the band separation in 1974. Because of their unwillingness to release anything that was not Moody Blues standard, they chose to disband instead. Creatively, they knew they had to re-energize, to gather other musical experiences, and to learn more about themselves as individuals if they were ever to come back and create as a group.

The press calls them “dinosaurs,” the dictionary definition of which is “extinct.” If the Moody Blues were no longer together, that description would be appropriate. If they were still together but playing only music they had composed ten years ago, I would deem the terminology acceptable. If they were still producing music but hadn’t advanced with the times, I could stretch the definition to be accurate. But this band has never stopped its development. Not only does their early material seem to be timeless, and not only have they continued to create, but they have matured and developed. In fact, their current album, The Other Side Of Life, contains material that ranks with the best the band has ever conceived. Dinosaurs! Ha! Advertisement

Of course, Graeme Edge does joke that he’s always been too old for rock ‘n’ roll. But that’s Graeme poking fun at himself in his delightfully charming humor. If, at 45, his life’s motivation is live playing, one doubts that he’II ever be too old for rock ‘n’ roll. How then could he have possibly been too old for it when he began playing snare drum in the Boys Brigade (similar to the Boy Scouts) at age eight in his hometown of Birmingham, England? He was enticed not only by the snare drum, but also by the fact that he could wear long trousers! “You couldn’t wear long trousers in England until you were 12. It’s not so much like that now, but it was back when I was a boy—back in 1814,” he teases once again.

Graeme’s dad, who had been a music-hall singer, and his mom, who was a pianist, had the biggest house in a neighborhood where some boys who were older than Graeme had a group together. They stored their gear at the Edge house, and when they weren’t around, Graeme found himself gravitating toward the drumset.

His parents then set him up with a few months of drum lessons, but mostly Graeme taught himself by listening to records and inventing his own style. “There was no one around in England to teach us rock ‘n’ roll drumming, because we were the first. We had to make it up as we went along,” he explains, adding that he enjoyed listening to Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Joe Morello, and John Bonham, but worshiped Ginger Baker. Advertisement

“Ginger Baker was the first drummer I had ever seen who had a real technique—who had sat at home and worked on his technique properly instead of just listening to records and trying to copy them. He was the first person I saw who played things like paradiddles, flamadiddles, and more complicated things with the right technique. I didn’t know what they were called, but I knew the sound of them. When I saw him playing them, I suddenly realized why I was always getting caught on the wrong hand, and how drummers like him always had plenty of time to get to the cymbal. I was always diving for it, which tended to make me speed up a little. The biggest thing I learned from him was to read music, get some of the books, and practice. Reading was valuable; it taught me that by just copying the sound you can get into trouble. You can play something that sounds similar, but because you’re not putting in a double beat on one hand sometimes or starting with the correct hand, you can end up messed up. You can get the fill to sound exactly right, but to get back to a standard pattern, you have to sort of uncross your arms, which makes you speed up. Then you’re not in control of the situation,” Graeme explains, conceding that, although Baker was an important influence, Edge’s playing style is much more sparse. “A lot of my style has been formed by the music I’m playing.”

His first professional job was with the Blue Rhythms, the band who had stored their equipment at his parents’ house. When that band fell apart, Graeme continued to play, but his parents convinced him to go to college, where he studied and practiced design estimating for bridges and such. He joined the Silhouettes while undergoing his required trade training, and simply lived two very exhausting years working and gigging. He obtained his degree at the same time that the band changed its name to Jerry Levine & The Avengers, which played the usual hit-parade pop material. (“Locally, they called us Jerry Latrine & The Four Flushes, “he laughs.) When American rhythm & blues turned the young musicians upside down, they changed their name yet again to the R&B Preachers. That lasted about 18 months, when all of a sudden . . . .

GE: Ray Thomas turned up at my house. We had met because he was in a rival band called El Riot & The Rebels. He was with Mike Pinder, and they had John Lodge in their pocket. I was playing in the R&B Preachers with Denny Laine, amongst others. They wanted to get me and Denny to join up with those three to form a band, because some of the other players were into rhythm & blues and some weren’t. They were quite correct in assessing that it was Denny and I in our band who really wanted to play it. So we joined up and formed a band called the M&B Five, named after a brewery in Birmingham called Michells & Butlers. The idea behind the name was that English pubs are quite large buildings and M&B owned a lot in the area. On the top floor, they had a big room where the local people could assemble for various functions. We had this idea that, if we named ourselves after the brewery, they might let us play in the assembly room and even give us a bit of sponsorship. The M&B Five worked for about three or four months, and Michells & Butlers answered the letter. They didn’t want to know about sponsorship, so we didn’t want to call ourselves M&B Five anymore, but we had gone down so well in such a short time that we didn’t want to change our initials. Blues was easy for the “B,” but we needed to come up with something for the “M,” so we came up with Moody and the band turned into the Moody Blues. Advertisement

RF: What music were you playing?

GE: We were doing the usual blues stuff at the time, sort of “Smokestack Lightning,” “Twist And Shout,” and “P.S. I Love You,” which was before The Beatles. Everybody was playing those, but those geezers were the first to get them onto record. But thank God they did, because they had the talent to throw open the doors of America to all of us. We decided we were just going to play for fun and not try to make it anymore.

RF: Why did you decide you weren’t going to try for success?

GE: We were too old for rock ‘n’ roll. We were just screwing around, and we got to play at nightclubs that trios usually played. We were playing in a place called the Old Moat, when a friend of some guys who worked for Seltaeb—which is Beatles spelled backwards—The Beatles’ marketing company, brought the Seltaeb guys around. They asked us what we wanted, and we told them all the equipment we wanted, tongue well in cheek. They came back a week later with a van full of all this stuff. So we signed this piece of paper, and they robbed us blind, of course. But they set things up for us, I suppose, and they got us our first recording contract.

RF: What was it like recording for the first time?

GE: It was very strange and unnerving, because it was the first time I got stuck in a box to play. We’re talking two-track days. I had to use cans [headphones] for the first time, and I found that weird, especially in those days because they weren’t very good. I was really quite overwhelmed by it all. Advertisement

RF: Were there any songs we know today in those first sessions?

GE: No. The first time we went in was just to demo up some stuff, so we just played some of the stuff we had been playing on stage. The first serious time we went into the studio, they got a whole bunch of American demo records for us to listen to, and we found “Go Now.” We recorded it, and it was pure animal luck. After the stroke of luck with “Go Now,” we couldn’t find a decent follow-up. The next song we recorded was, in fact, “Time Is On My Side,” which the Rolling Stones promptly stole and made their own. That sort of flattened us. The next one we recorded was a very good song called “From The Bottom Of My Heart,” but at the time, if your immediate follow-up wasn’t a hit, you were elbowed. That one did enough to get us work and sell some records, but that was it.

Denny Laine went into a sort of panic, or a career-survival thing, and he decided he wanted to go out on his own. At the time, Eric Burdon was reforming his new Animals, Manfred Mann was looking for a new bass player, and we were looking for a lead guitarist, so we took a huge ad out in the New Musical Express, “Three top 20 bands . . . .” Manfred Mann got Klaus Voorman, Eric Burdon reformed the Animals, and we got Justin Hayward—probably the finest songwriter in all England, from an ad in the newspapers.

RF: Justin’s influence was entirely different. How did your playing have to change?

GE: Denny Laine leaned towards a more jazzy drumming. He liked me to be much busier with lots of short, busy little phrases. If you listen to a record called Moody Blues No. 1, there are three or four tracks that are far from mainstream pop. There are some strange time signatures and constant changes in rhythm patterns, which are the kinds of things Denny Laine liked to write. Drummers who are any good play the correct drums for the material, not the correct drums for their egos. I liked the technical aspect of playing that material, but it did lack feeling. What I enjoy about Jus’ work is the depth of emotion, the soul, and the obvious effort that has been put into writing the song. With regard to the drums, his songs really don’t want hitting every-drum-in-sight Keith Moon fills. The word delicate comes to mind. There’s great satisfaction in holding a simple beat right to the edge of monotony and then giving the song a release in the right place, kicking it on. Justin likes big tempo changes in a song, but once he gets set into a groove, he likes to stay with it for a lot of bars, and Jus likes his fills in what you would call the standard places. There’s nothing unusual about where he calls for a fill. In fact, his songwriting is very correct in musical terms, more so than John’s, which is why he’s such a good songwriter. John’s an excellent songwriter, too, but John does tend to have the odd two-beat bar and some unusual sort of positions musically. Advertisement

But regarding your question, Justin’s influence grew slowly. He just started in, and the poor chap had to get up and sing “Go Now” for a while. I’m sure that was not a happy experience for him. We had to leave the country, too. We went to Belgium, because we owed too much tax to live in England—the standard story. Management pissed off with all the money. They left us in Belgium, and John Lodge had to sell his amplifier to buy us ferry tickets. From there, we moved to Paris, and we were taking Paris a bit by storm, actually. We got an invitation to play at Olympia, with Tom Jones, early in his career when he was considered a rocker as opposed to a lounge act. His agent, a very dear man named Colin Berlin, got us work in England that consisted of doing these bloody nightclubs, which were a rock ‘n’ roll groups’ graveyard. It was cabaret, and what a lot of bands did was learn to imitate other acts and virtually stick on a red nose and a straw hat. The first time we did it, we died. It was awful. We thought, “What can we do with two half-hour spots?” So we thought we’d write something.

RF: That’s why, on stage, Justin introduces Days Of Future Passed as having started as a stage play.

GE: Right. The first time Justin played it for us we knew it was something special. We worked it up so we could start playing when we were supposed to and play right through to the end without having to stop or tell any funny stories.

The record company had just developed this new sound system, which was just stereo, really, but it was their own line called Deram Super Sound, DSS. To show the versatility of their equipment, they were doing a lot of ying-and-yang records, like a brass band with some juicy violins on the same record. We were the rock ‘n’ roll band with the orchestra. We had the Mellotron. We were using strings and violins, but we were supposed to record Dvorak’s New World Symphony with producer Peter Knight, who was brilliant and very well established. They gave us three days in the studio, and we took ten to make Days Of Future Passed. When it was played at their Monday meeting where all the new products were played, they had a guy there from America named Walt McGuire. He was there as an observer. They expected Dvorak’s New World Symphony, and when they heard what we had done, they went bananas. They were ready to crucify us, but Walt McGuire said, “I can sell that.” He brought it over to America, the album went to about 30ish, and “Nights In White Satin” got to about 18, which was enough for them to let us carry on. [Three years later, “Nights” was inadvertently rereleased by a D.J. who liked the song. It hit number one, bringing Days Of Future Passed to the number-one position as well.] Advertisement

RF: What was it like to work with an orchestra?

GE: We never did. If you listen carefully to that record, the orchestra is never playing when the Moodies are playing. They play the links between the songs, but when the Moodies start playing, it’s just us and the Mellotron. On the album version of “Nights,” they come in about halfway through the last verse, and it is the orchestra in back of the poem, but outside of that, it was never at the same time. In fact, we’d record the songs, shoot them over to Peter Knight as fast as we could, and he was writing the links and recording them.

RF: It almost surprises me that you didn’t work with an orchestra, because so much of your music sounds orchestral. There are songs where it sounds like you’re playing timpani and big cymbal crashes. What was all that?

GE: Timpani and big cymbals. Oh, did we have some bloody nerve! I’ve seen John Lodge, Mike Pinder, and Justin Hayward sit in the studio for two days trying to get a bloody cello part.

RF: Why?

GE: For some reason, we developed this set of morals that we weren’t going to have anybody but ourselves on the records. I think one of the reasons was that we were so upset by the fact that everybody thought Days Of Future Passed was a rock band with a bloody orchestra over everything. So it sort of became an issue. On the next album, we put: “All instruments played by the Moody Blues.” We listed everything everybody did. Advertisement

RF: Of course, a lot of people thought you were quite pretentious because of this sound.

GE: Being called pretentious used to hurt us. I didn’t quite understand what it meant. I looked it up, and it means pretending. I knew we weren’t doing that.

RF: How much input did each individual have when it came to recording this music?

GE: We used to sit around a coffee table, and the songwriter would play the song. Everybody dove in, argued about ideas, put things backwards and forwards, and the songwriter just sat there and put his piece in as well. We’d play a bit and try it out, and when all the ideas were put forward, the songwriter picked which ideas he wanted and which he didn’t want. The final authority, even above the producer, is the songwriter. Sometimes when you have a great idea and that songwriter can’t see it, you have to bite your knuckle. But you need to, because you know that, when it’s your song and your turn, you’re going to get the same treatment. Then you spend bloody hours getting it right and usually discover that the third take was the right one.

RF: What were some of your favorite drum tracks?

GE: I was very proud of what I did on “Stop” with Denny Laine. I like “Legend Of A Mind,” especially where we change into the Indian stanza. I think the tempo change is done in such a way that you don’t suddenly notice that we’ve moved from 4/4 into what it became. I can’t remember the time signature, because Indian music is like a giant riff. Of course, it can be measured out, but you end up doing something daft like 17/8, and it’s best not to think of it in those terms. It’s best to picture it as the Indians do—as a riff. I was very pleased with the way I crossed over there. I like playing “I’m Just A Singer In A Rock And Roll Band,” because of what it meant at the time, although the drum track itself is not particularly involved.

RF: Something like “Isn’t Life Strange”—which is so creative with all the different sections, laying out and coming back in—is almost your standard.

GE: That one and “Question,” which follows a similar pattern.

RF: How was stuff like that born?

GE: It’s down to that coffee table. I can’t remember who said, “Let’s not have the drums in here.” It wouldn’t bother me at all to be in for part of the song and then not in for part of it. I wouldn’t start to worry that I wasn’t all over everything. The only thing that concerns me is if it works for the song. Advertisement

RF: You more or less indicated that the coffee table creating was past tense.

GE: We don’t do it so much now, because with modern electronics, there’s so much more pre-work done in the home. The equivalent of that now might be that Jus will ask me to help him with a program on his drum machine for a song he’s working on. With these drum machines, we can get a bit of a program down, although obviously, we don’t put the finished one down because things have a way of developing in the studio. We get a bit of a drum program down, we use that to run a couple of keyboards, and then Jus will put a couple of guitars down. We ram all that onto tape with some very good home equipment. It often can be used almost as the first take of the song.

RF: The electronics have had quite an effect.

GE: It’s totally changed recording. Groups don’t really play together anymore in the studio.

RF: How do you feel now being in the booth all by yourself, whereas before you got to play with other musicians?

GE: I love it. Before, I used to play with the other members, but it was a very, very basic track. They were in there just to give me some music to play with, because they knew that they were going to replace themselves at a later date. And if not that, they were going to have so many things on top of it that it was going to become virtually meaningless. That meant that I was playing with some very, very bland music and trying to play orchestral Moodies drums over the top of it. That required quite a lot of imagination. Now, I don’t put the drums on until there’s a whole bunch of music down. I’m playing with more than I’ve ever played with, so I love it this way. I used to have to play sort of safe fills that wouldn’t get in the way of anything anyone else played. If I played anything more elaborate, it would screw up perhaps an interesting triplet run someone might have come up with.

RF: There must be some more current drum tracks you’ve done that you like.

GE: I like ”The Other Side Of Life,” but I love the song. The drumming is good on it, too, though. “Running Out Of Love” [from the LP The Other Side Of Life] is great. I love the backing track for that. When the vocal went on it, it changed the style. The track was very much swamp music, like Creedence Clearwater, before the sweet English vocal went on the top. I still have just the backing track. I also like what I played on “Veteran Cosmic Rocker” [from Long Distance Voyager]. It’s so outrageous, and it has a touch of Ginger Baker about it. Advertisement

RF: One of the interesting things was that little marching drum thing in “The Hole In The World” on The Present.

GE: The drum intro to “Under My Feet.” Another name for that is “Hole In My Shoe,” and actually, in my opinion, where it should have been recorded was the hole in the record. I hated it.

RF: Yet, you were out front for a change.

GE: I just don’t think it worked. I should have done at least 20 snare overdubs and had it as mass snares with that lonely, powerful guitar over the top. But because people were thinking about performing it live, it came out to be one snare, and I thought it sounded too small and too real.

RF: Wasn’t it impossible to reproduce on stage half of what you did in the early days?

GE: There’s never been a song that we’ve wanted to perform on stage that we haven’t managed to do.

RF: Even back then when technology was so limited?

GE: Even back then. That’s not to say that there weren’t a couple that would have been impossible if we had wanted to do them. One of John’s that I’ve always wanted to do, and one that we could have developed in the same way we developed “Isn’t Life Strange,” is “The House Of Four Doors.” I always thought that was a smashing piece. That would probably be very difficult, because as he goes through the various doors, we play the different styles of music, but that’s why I fancy it.

RF: There is a little instrumental piece on On The Threshold Of A Dream called “The Voyage.” Was that fun to do?

GE: That was great. There was this idea and that idea and the other idea. Sometimes we’ve got so much going that it amazes me. They just said, “Alright, put a bass drum in there for 32 bars, and we’ll figure out what we’re going to play there afterwards.” I’m sure you’ve heard this before, but a lot of performers work better with a deadline—calling your own bluff, and pushing yourself into a corner. There’s nothing like a bit of fear to get the creative juices flowing. Advertisement

RF: What kinds of effects were you guys fooling with in the studio in the early days?

GE: We always have been, and still are, open to any new technology. We used the first dbx. In those days, they were not these simple little things we use now. We switched it all through to high treble and then brought it back down. It cut down on the bloody hiss you get with generation. I’m glad we did worry about sound quality in those days, because now the whole back catalog is on compact disc, and it really matters. We had one of the first Moogs in England. We used to do crazy things. At Decca, they had an echo room that was actually inside the roof, and there was a speaker at one end and a mic’ at the other end. For the echo, they actually put the guys at the speaker, and the length of echo was adjusted by how near and far you moved the mic’. There were two huge steel plates to keep it bright. I sat up there with a cricket bat for an effect. I’d have everything all set up, the music coming through in my headphones, and I’d hit it, bang, on the steel plates. I had the job because I was the drummer.

RF: Did it actually make it onto vinyl?

GE: No, it was a terrible failure. But we didn’t know it wouldn’t work until we tried it.

RF: Are there any off-the-wall things that you can actually remember making it onto the record?

GE: In the Lost Chord poem, everybody loves the way I break and scream and laugh at the end. If you listen carefully, I do a spoonerism—where you mess words up, like instead of saying sweet potatoes, you say peet sowatoes just about two words before I break out into laughter. I stepped to one side and delivered it again. I maybe did it a couple of more times right, and then I listened to it. They all were looking at me, because they didn’t know how to say, “Don’t you want to hear the one where you crack up?” I was thinking about this as a piece of art. They played it for me, and I had to own up. It worked.

Most of the effects that we got we actually set out for, though. There is one of the poems with a big intro like a spaceship kind of noise. That was Mike and I on two great big Moog synthesizers. If you listen to “Thinking Is The Best Way To Travel,” with ‘phones, God, it took us ages to get that to move around your head. Advertisement

RF: Today, we have such advanced technology, which should be making things easier, but it seems it takes longer to make albums.

GE: Because there are more things to experiment with now. You’ve got to be very, very careful. Do you remember the Syndrums when they first came out? It was, “Wow, great!” And I was just like every other idiot. It was all over one song on Long Distance Voyager. I listened to it for about three days, and I thought, “I’ve got to get back into the studio and take that thing off, because I’m going to be ashamed of that in two years’ time.”

RF: You had a great deal of foresight, because people didn’t realize it was a fad.

GE: It just seemed obvious to me after a couple of days that it was very faddish. It has no musical quality, actually. It was just an interesting new piece of technology. On this last album, we used a lot of sequenced material, but there were stacks more of it recorded, digested, and elbowed. We’re damn proud of our music, and we want it to be listenable in ten years. So although we want to be there at the front of technology, we are very careful of being faddish. We listen to it and ask, ” Is this musical?”

RF: When you guys decided to call it quits for a bit, was it with the intention of being for just a while, or was it an actual breakup?

GE: None of us ever had any doubts that we would perform and record together again. I think it grew from that attitude of playing all the instruments ourselves. Also, we had become very, very popular, and we had become totally isolated from the world and totally incestuously lumped all together. We went in to make an album, we had about four tracks, and it was junk. You could hear that one song we previously recorded was the father of those four songs. So we wiped that lot, and we realized we couldn’t work together and make stuff that came up to the standard that we wanted. So we went out to get other experiences working with other people and also to let that major stardom thing die down. Advertisement

Those were strange times. Now the rock stars are people. Admittedly, they’re sex objects and all that, but they’re people. But in ’72, people thought of us almost as semi-deities. People used to ask us to bless them. They thought we were in touch with some cosmic thing, and that’s horrifying. Mike Finder never recovered from that.

RF: If you don’t have your feet on the ground, something like that could blow you away. Is that what “I’m Just A Singer In A Rock And Roll Band” was all about?

GE: Yes. We were just asking the same questions as everybody else. There’s a great line in that song: “If you want this world of yours to turn about you, and you can see exactly what to do, please tell me, I’m just a singer in a rock and roll band.”

RF: So you decided to back off for a while.

GE: I made two solo albums, and I lived on a yacht for 15 months.

RF: Tell me about your solo albums.

GE: I like the second one more than the first one. I did them with a guy named Adrian Gurvitz, because I don’t have the musical

expertise to work on my own, and I sound like a bullfrog with somebody stepping on its toe when I sing, so you can’t really call it a solo album. It was really a collaboration with Adrian. We co-wrote the material, but for marketing purposes, it was called the Graeme Edge Band. It was great working with Adrian, because even though I love Moody Blues music, like any drummer, sometimes I want to really give it some stick. It was also very much removed from Moody Blues music. I wanted to get completely away, which is why the name of the first album is Kick Off Your Muddy Boots – muddy boots being Moody Blues. Advertisement

RF: After working with the same people for so many years, working without them must have been a shock to your system.

GE: I was very nervous about it at first. It was a whole new bunch of people who didn’t owe me anything. I had no history with them, they didn’t need to be considerate of my feelings, and it was, “Come on asshole, get it together.”

RF: That must have been an awful time, in a way, but exciting.

GE: It was exciting. I had some weird dreams at night, which is part of the reason I went off in the boat. After that experience, I had to go for my sanity and get myself back together.

RF: What about your second solo album, Paradise Ballroom?

GE: I felt I had to prove myself. The band was sort of hovering on coming back together, and I felt I needed something to say, “This is what I’ve been doing, this is where I’ve been, and this is where I am now.” A year on the boat really built my confidence in myself, and I went back and really took charge of the second album, so much so that Adrian and I never worked together afterwards because he’s a very powerful ego of a man, and I asserted myself a couple of times and said, “That’s my way. Stuff it.” It was a little bit unfair to him, because he put a lot of work into the album, but I never had the slightest intention of going on the road with it because I always knew the Moodies would be back. I suppose in a way I used him, but I suppose in a way he used me, too.

RF: You both got something out of it.

GE: If you look at the release dates, all the solo albums – mine, Ray’s second one, Hopes, Wishes & Dreams, Jus’ Night Life, and John’s Natural Avenue – came out in the space of three months. It was all of us turning to each other and saying, “There you are. Can you respect me now? Can we work together?” From there, we got back together and came over to America, because Mike Finder was living in America at the time. All of us moved to him, rather than his coming to us, because we really wanted to have completely the same setup. I don’t want to say too much about Mike because I don’t want to put anybody down, but he got religion bad. One week Advertisement

he was a Hopi and the next week he was worshipping the sun. He hardly worked at all on the album. Most of the keyboard parts were done by John or Justin, who, given enough takes, are very competent keyboardists. Poor Tony Clarke was just going through a divorce, and it took Justin half an hour to talk him off the edge of a cliff. That was the last album he made with us. That’s just what you need when you’re making your comeback album. It was a bit of a mess, but the four of us came out of it solid. We tried to get Mike Finder to come out on the road with us, but he wouldn’t. He had totally lost his music – totally lost his nerve. We don’t even know his address. We have to send his royalties to a lawyer. From there, we got Patrick Moraz in, originally as a pickup musician, hoping that Mike would come in on the next album.

RF: With regard to the solo experiences, certainly there are advantages and disadvantages to working with the same core group of people for so long. I would assume that, in one sense, it could be musically unhealthy, though.

GE: It depends on what your attitude is as a performer. I’m quite happy to be recognized as part of the Moody Blues. I’m not really that bothered about being recognized as a brilliant percussionist. The band being recognized as brilliant is great for me because I’m part of that. But it has stylized me. I did become a little bit conscious of this about three years ago, and I started playing in a little jazz band called Loud, Confident & Rung. I don’t think the same lineup has been on stage twice, and it’s great. Advertisement

RF: As you said, you’re not a soloist, but an ensemble player. You all went off to do your solo projects, and they weren’t massive successes. But you all came back together, and the total was greater than the sum of its parts.

GE: Absolutely. It was a great relief, which was felt much more on Long Distance Voyager than on Octave. On Long Distance Voyager, it was great because it was very comfortable. We knew what someone was going to do and where he was coming from. At the same time, after that period apart, there were new, interesting, and exciting facets of each person’s per forming abilities that weren’t there before. So it was the best of the old and some great new stuff as well.

RF: You have written songs. What other instruments do you play?

GE: I use the piano, but there’s no way you could say I play it. When I walk up to the boys with the chords, they sort of give me a sweet, condescending smile and make it work. I get close enough to let them know what I’m trying to do. Advertisement

For us, publishing is quite simple. The geezer who gets the publishing is the bloke who, if he hadn’t done what he did, the song wouldn’t exist. I know drummers who think they ought to get part of the publishing for coming up with their parts.

RF: When did you start writing poetry?

GE: I always have. When I was eight, I had a composition to do in school, which I wrote in rhyme.

RF: How did the poetry enter into the musical concept?

GE: We were recording Days Of Future Passed, and we were gigging as well at the time. I was driving with the roadie on the way to a gig, and I wrote “Cold Hearted Orb” and all of that, on a pack of cigarettes. Next time we were in the studio, I just said, “What about this?” They all said,” Great ” That’s what made the overtures happen.

RF: This current album has some interesting material. Watching you flailing away on one of the new songs, “Rock ‘n’ Roll Over You,” made me think that it wasn’t much different from heavy metal. Advertisement

GE: That song scared the pants off of me. It was such a style departure in the backing- track phase. John had a very fixed idea of what he wanted, and I went on quite early, so I didn’t hear the rest of the stuff that was going to go down. He wouldn’t let me move around the drums, which I thought, at the time, would be much more interesting. It’s all on one drum, which seemed a bit monotonal. But it turned out to be right. He could hear the rest of it in his head. And I’ve got a feeling that it will be one of those songs that’s really going to develop and change, and we’re really going to mess with it. It’s like “Legend Of A Mind,” which bears no resemblance to the recorded version. I have a feeling that “Rock ‘n’ Roll Over You” is going to go that way. And conversely, a song I really like on the album, “It May Be A Fire,” doesn’t work on stage. It’s not a disaster, but I know that it’s going to be one of the songs that, when we do the next album, will be dropped. And yet, if you had asked me before we started playing live, I would have said the opposite. But you don’t know these things until you start playing them. I’d love to go in and record “The Other Side Of Life,” having played it so many times live, now.

RF: What a creative drum chair! Why do you think that is?

GE: First off, it’s the abilities of the people I’m backing. A good drummer can’t make a bad group good, but a bad drummer can sure make a good group bad. When we’re on stage, we do play together. Some groups thrive on a certain clash between two instrumentalists trying to outdo each other, which gives it a certain abrasive quality but creates excitement, which is good. Our band isn’t like that. When it’s somebody’s turn on lead, everyone lines up behind him. If anybody makes a mistake, this band regroups and gets behind the geezer who has made the mistake. Nobody makes a mistake on purpose. He’s the person who is lost, so the rest are really hanging onto what they know is right.

I did something recently, and there was no way they could cover for me. On the song “Gemini Dream,” there’s a guitar solo in the middle. The first lick of that solo is played at the end again, which comes up to a sort of staccato-style end. I went steaming straight into playing the end in the middle of what should have been the guitar solo. But it worked out okay. Justin carried on with the guitar solo, and the rest of the boys played the end with me and what would have been the finish. Then we dropped back to finish the guitar solo. People must have thought it was a weird arrangement, but we got away with it. Advertisement

RF: What are some of your favorites to play live?

GE: I still love “Nights.” As soon as we start that song, a wave of electricity belts from the audience across the stage. We get the feeling that the song means so much to so many that we give it everything we can. Although I think the development is finished, I love playing “Isn’t Life Strange” because of the arrangement, with the way we built it up and developed it. We’ve taken that to its full extent, but John Lodge is proud of it and I love playing it as well. There are some parts where I don’t play at all, which gives Ray a great opportunity to let the flute really speak into the hall without my cymbals. Also, I have three solo fills in it, which I really enjoy. I play the first one very simple, I build it up and put some triplets in the second time, and the third time, it’s just triplets all the way around the kit to kick in the chorus. I get to go across the song like a herd of elephants, which I enjoy doing. Justin has written some lovely songs that I like, like “Sitting Comfortably.” “Melancholy Man” by Mike, I thought, was a great song.

RF: You really use the audience to charge you. At Radio City Music Hall, you made the comment that you felt too far away from the audience.

GE: I look around the audience to find as many who are into it as possible. I can only see about five or six rows back, so I’ll look for the demonstrative people who are chair dancing or playing air guitar or air drums. I use them to leech energy from.

RF: You said before that you love to play live. You’ve been doing it for so many years. Do you still love it?

GE: Oh yes!

RF: The road and hotels?

GE: Oh no. I said I love playing live. But you’ve got to put up with one to get the other.

RF: Are you ever too old for this?

GE: No.

RF: But you were too old when you started.

GE: You’re damn right. I’ve always been too old for rock ‘n’ roll. Nobody ever says that jazzers are too old.

RF: But let’s get serious. Everyone says your body changes when you get older, and it’s harder to do certain things. How do you counter that? Have you felt any of that at all?

GE: Oh yes. I’ve got a knee problem. I suffer with tendinitis, but I’ve got an ultra sonic machine. I’ve altered some techniques and I’ll probably have to alter a few more, but I’m reasonably fit, and I’m only 45 for God’s sake. Advertisement

RF: But when you’re talking about your body, 45 years old is very different from 20 years old.

GE: You’re damn right. You don’t see any 20-year-old marathon runners do you? They’re all 45, because you get a different kind of strength as you get older more tenacity and more mental strength. I have to treat my body very differently now, of course. I used to drink scotch on stage, but now I have to point myself toward the gig all day, keep my act clean, get sleep, and all that. I love to take a nap at 4:00 in the afternoon, which keeps me calm because I still suffer from bad nerves.

RF: Why?

GE: I think it’s anticipation, excitement, and the adrenaline. It’s not fear.

RF: I can’t believe you’ve put yourself through this all these years.

GE: But when I hit that first note, I just want to explode with joy inside. Sometimes I just burst out laughing while I’m playing, because I’m having such a good time. I almost feel guilty about feeling so happy.

RF: You have all sorts of gear. How much do you care for yourself, and what does your roadie do?

GE: He has to change the programs for me. It’s only a question of pressing a button, and then I’m back. I could handle it, but that would mean I would have to have all that gear up there with me. What I have on stage is a start switch, a program change switch, a tempo control knob, and all the controls to the acoustic drums that I use as triggers. Advertisement

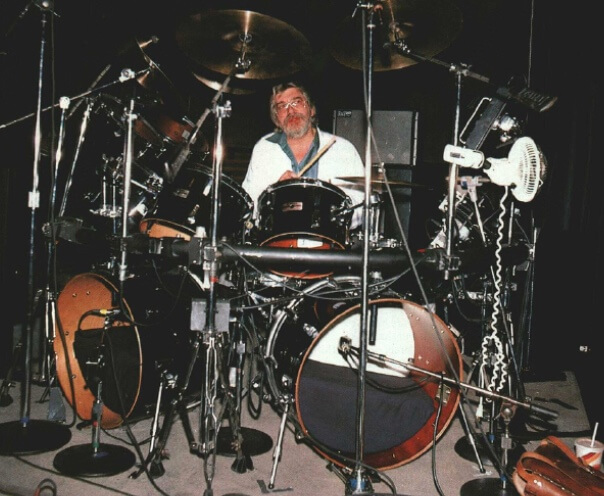

RF: Can you detail your very state-of-the-art equipment?

GE: Just the old-fashioned acoustic way, I have two overhead mic’s, which are there to pick up the cymbals. I don’t think anyone has yet successfully synthesized cymbals. You can get one great cymbal sound, but it’s just the one sound. Any drummers worth their salt can get at least seven or eight sounds out of a cymbal, depending on whether they hit with the flat of the stick, or on the edge, or on the bell, etc. I have an emergency backup should everything die, so I have an acoustic mic’ on the bass drum and two acoustic mic’s on the snare. The acoustic snare mic’s are actually used as well. The bass drum mic’ never is. The guy out front mixes that in and out at will. Then I have C-ducer mic’s, which are contact mic’s, all going through a C-TAudio electronic trigger unit that has been beefed up by my electrician. It’s really made for fiddles, cellos, and things like that, and it was a bit delicate for the explosive impact of the drum. We had to brutalize the inside a bit more so it could handle the immense power.

RF: Why do you use that?

GE: Because I don’t like the look of standard electronic pads. I don’t like the feel of them either, and the rest of the boys really want the acoustic sound of drums on stage. It sounded like there was a great big hole in the music when I did try to use the electronics just coming out of the side speakers They said they couldn’t seem to rock or drive without the actual air being pushed behind them. Everyone agreed that the acoustic kit should be there, but at the same time, I wanted to have the availability of electronics. The acoustic trigger unit then goes into a Percutor drum machine. It’s a German machine that plays electronic chips. It’s not a sequencer; it’s just what makes the noise from the acoustic trigger. That has several sounds that you can interchange. I have three triggers in the snare and four tom-tom sounds. I just get a real good sounding tom-tom, and I don’t have to worry about changing the tom-tom sound. If I want it to sound slightly differ ent, I just bang the kit up and down a little. I’ll get the drums mildly in tune with the track. You don’t want to get them perfectly in tune with the track, because part of the feel of the drum is that it is standing just a little bit away from being perfectly in tune.

All that goes through a Yamaha mixer. Also going through the mixer are two Linns that have been severely modified. I can run them both at the same time. I have the tempo control next to me on stage so I don’t have to fiddle with the button on the actual Linn, and the choice of the song pattern is up there for me. It gives me the availability to put in claves or timp, or to use the snare on that machine for extra emphasis on certain parts of a song. I have control of the tempo and switching it on, and we use that to run through an SDX-80 MIDI box. I use that to send MIDIed signals to Patrick’s Kurzweil and [auxiliary keyboardist] Tobias Bishell’s DX-7. I can then trigger sequences in their equipment. I can be sitting up there and trigger cello lines from Patrick’s stuff or those spacy effects that might come along once or twice in a song, like some of the noises in “Rock ‘n’ Roll Over You” and noises in the beginning of “Wildest Dreams.” It would be a waste of time tying up a key board just to make that one sound, or you’d have to go back to the bad old days when keyboard players had 15 keyboards just so they could have one sound halfway through the song, once. Now I can run it from my equipment, leaving the keyboard player to concentrate on playing the song with as much of the human touch and feel as he has the talent to do. I also have a Simmons SDS5 system with four pads stuck up on the kit. They’re mostly used for effects, like in “Rock ‘n’ Roll Over You.” I love all the electronic stuff today and the challenge of making it work. It really has kept me interested. Advertisement

RF: What kind of acoustic set do you use?

GE: Yamaha drums and Zildjian cymbals.

RF: When did you get into the double bass?

GE: I got into it, and I’m back out of it now. I must admit that it’s really there just to balance off the kit, because I have so much electronics on the side.

RF: What was your equipment like back in the early days?

GE: I always played Zildjian cymbals. I used to have one hi-hat and one enormous 22″ crash ride that you could never dream of using nowadays. You hit that once, and it was over in about ten minutes. In those days, they didn’t used to close-mike you either. I had an Olympic 2 1/2″ wafer snare it took me years to believe in deep snares and the rest was a Premier kit. I had 9″, 12″, and 14″ tom-toms and a bloody great-big 24″ bass drum. We had to stuff it with toilet paper.

RF: What was required of a drummer in the ’60s as opposed to what is required of a drummer in the ’80s?

GE: In the ’60s, speeding up was perfectly acceptable – controlled acceleration. The disco boom really got people metronomic in the way they listen to music. You really have to keep strict tempo now. It’s gone full circle, because between the two periods, there was a period where you had to be very jazzy in your playing, but it’s come past that again. It’s back to a good, strong backbeat. You have to make the fills effective by their sparseness and their statement when they do come in.

RF: Justin made a comment in an interview that, in your more current albums, there is a lot more space in the music than there was in the ’60s when there was so much going on.

GE: We used to pile it on.

RF: He also said that on the current albums there is a lot more emphasis on the drums and bass.

GE: Which means that you have to be much more strict and more disciplined, because you’re carrying so much more of the sound and the responsibility.

RF: On the old recordings, you can barely hear the drums.

GE: That’s the price you pay when you’re doing multilayering on a four-track machine. By the fifth or sixth generation, it’s bye-bye drums. Nobody on earth could have had the drums high enough on the original mix to compensate for that, or if you did have it high enough in the original mix, nobody could play with it because it would be so offensive musically. Advertisement

RF: Is there anything else you can think of that the drummers of the ’60s and ’80s would find different?

GE: Well, the obvious electronic applications that are available now. In the old days, your drums were your drums and your sound, and that was it. Maybe you could use a couple of cigarette packs to dampen it down so it didn’t ring so much in the studio, but that was about it. Now, you can get these great tom-tom sounds with the Roland and the Simmons stuff. Even though it’s touch-sensitive, you get different noises from whacking it in the middle and whacking it two inches from the middle. You get more attack and a shorter decay if you move off the middle. Also, you’ve got to be much more prepared to operate with sequencers to operate with the tempo being supplied by a machine or something else. At the same time as you’re doing that, you’ve got to be able to drop the offbeat down so it still feels human. It’s much more technical now, and you’ve got to think a lot more about what you’re doing. And of course, in the ’60s, there were no rock traditions, so you were very much on your own in what parts you played. Now, of course, there’s a lot to listen to and learn from, so the rock drummers now can get all their rock grounding together in four or five years, whereas we had to make it up as we went along. All John Bonham really did was reverse the bass drum pattern, so instead of going boom, cha, boom, boom, he went boom boom, cha, boom. But what a revelation that was! All of a sudden, virtually with the same part we had all been playing for bloody years, he just reversed the bass drum pattern, and suddenly, there was this powerhouse. It had been right there for all of us, and none of us had figured it out.

RF: So now that we’re nearly out of the ’80s, what is the goal?

GE: Musically, I want to make another excellent album. Hopefully, a lot of people will like it and buy it. I’m not hoping this just so the album will go up the charts. If it goes up the charts, it will mean that a lot of people enjoyed it. That will enable me to carry on playing live, which is the thing I like doing most of all in all the world.

I personally would like to write a song good enough for the band to choose as a single one day. And I’d like to get another poem out soon. I’ve written several recently, but I’m not really satisfied with what I’ve written lately. Advertisement

RF: After 22 years, does it still hold the magic for you?

GE: Even more so. It’s more frightening now, but it’s more satisfying when you make it yet again. When you’re starting out, you know you’ll do it; you have to have that kind of confidence and belief in yourself. But when you’ve done it and done it and done it, then you start to think, “How much longer can I maintain?” That is a different feeling. So when you do actually continue to make it, it’s even more satisfying.