Louie Bellson

Louie Bellson

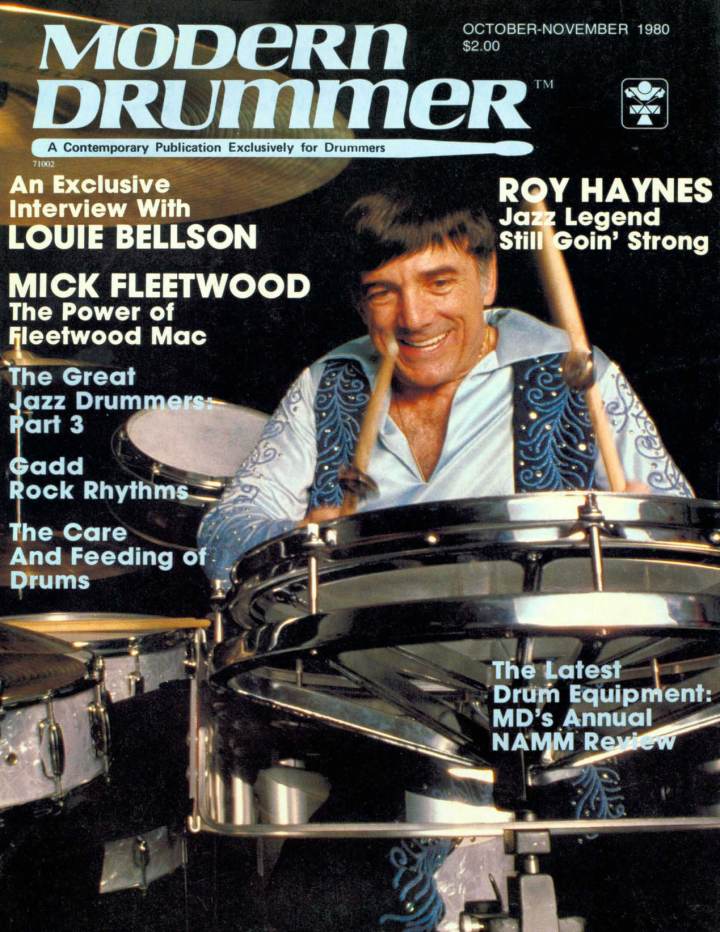

At the root of Louie Bellson’s talent lies a wealth of knowledge, perseverance and the hunger for constant improvement. His consistent quest to remain abreast of the times and changes is rewarding to him and his audiences all over the world. He was genuinely thrilled about the 1980 Modern Drummer Reader’s Poll in which he was voted #3 Best All Around Drummer and #2 Best Big Band Drummer.

“I’ve never won a downbeat poll in my life, or any kind of poll, except the last two years I won the International Musician which is an English Poll. Years ago. when it was Gene, Buddy, Jo Jones and I , I always placed fourth, a couple of times third, fifth and sixth, and I thought it was great that Modern Drummer readers put me among all those great players. What really flipped me out about this contest was the fact, that with my longevity so far, the young people felt that I was important enough to be in a category with Steve Gadd. That’s what made me feel good. It made me feel like my efforts to stay with the times have paid off,” he said.

Seated in the kitchen of his spacious country style home in Northridge, California, Bellson had a copy of the February/ March, 1980 issue of Modern Drummer opened before him. Before beginning the interview. Bellson wished to clarify certain points made in a column written by New York City drum instructor Stanley Spector. Advertisement

“Stanley Spector, who I know very well and who is a very competent teacher, talks about challenging the rudimental system and also makes mention of a drum workshop presented at the Newport Jazz Festival a few years ago. I remember that night very well. I was involved, as was Jo Jones, Elvin Jones, Roy Haynes and Mel Lewis. Stanley is a little bewildered as to the demonstration I did on jazz drumming. Well, it wasn’t a demonstration on jazz drumming. I was asked to, beside playing on the set, go out and give the kids a little something that I do at clinics where I demonstrate some basic fundamentals of drumming— not jazz drumming, but fundamentals of drumming. So, I’d like to clarify that point first of all. I didn’t demonstrate the long roll to pertain to jazz drumming, but as one of the rudiments.

“I would also like to bring to Stanley Spector’s attention that there’s nothing wrong with the scales of drumming. If anybody wants to put that down, then they might as well put down Charlie Parker for learning the scales and chords which he knew so very well that made him such an outstanding musician, and Dizzy Gillespie. too. There’s nothing wrong with the 26 basic rudiments. I feel you can obviously add more to that. I think there are some Steve Gadd rhythms now that have been played by this young man during the last few years where we could add 27. 28. and 29 to the rudiments. I don’t like to differentiate between rock, jazz and whatever else. I like to think like Ellington said — music. It’s all music, but in all of it, as I am sure Stanley knows, when a drummer plays a single roll and a long roll and a flam, there’s nothing else he can play. Everything else is a composite of those three, but you should learn those fundamentals and take it from there.”

Knowledge and the advancement therefrom, has been a major point throughout Bellson’s career. Training and practice began at age 3 and has not become any less important to him today. “I come from a very musical family,” he stated. “My father had a music store in Moline, Illinois for many, many years, so with four boys and four girls working in that music store, we had nothing but E flats and B flats coming out of our ears 24 hours a day. Advertisement

“At about 3ó my father took me to a parade and the minute I heard the drum section, that sound just enveloped me and I pointed to the drums and said, ‘That’s what I want to play,’ and he said, “Well, we’ll see.’ But when I got home from the parade. I just kept saying that I wanted to play the drums and he said that I was so definite about it. that he knew I was ready for my first lesson.

“I had wonderful training from my father. When this all started happening, I thought that maybe my father was taking me a little too far, but I realize now what he was doing. He was giving me a basic foundation. He said if I really wanted to learn how to play and make it my career, then I’d have to dig in and try to learn all there is to know and keep learning. He wasn’t talking just about the drums. He taught us a little bit about every instrument. In fact, we gave lessons in the music store when the regular classes

were filled up. He knew that we were all teacher-minded and could communicate with the youngsters, and two of my brothers are excellent teachers today. By the time we were thirteen years old, all of us knew every aria from every opera and he taught us how to listen to all music—symphonic music, jazz, chamber groups, string quartets, so I really have him to thank, first of all, for all the great training. It really helps today when Eddie Shaughnessy is gone and Doc Severinsen calls me to do the ‘Tonight Show.’ We don’t have much time to rehearse and they have to put things in front of me and I have to sight read. Now, if I didn’t read, I’d be stuck, or if I didn’t know how to play the various contemporary rhythms they have today, besides the jazz things, I’d be out of luck again.

“It’s up to the individual to keep up with the times. If you say to yourself that you are in the drumming field and constantly listen to records and go out and listen to players, you keep abreast with the times. If you want to just sit back and be lazy, then you’re copping out. If the drummers from my era are just going to play what we did years ago, that’s fine, but I think they’re closing themselves out, because some of the young kids are playing so many beautiful things, like Garibaldi, Gadd, Cobham, all these tremendous players. They’re doing things today we didn’t even dream about doing. Advertisement

“I also do at least 40 clinics a year, and I would not go a year without doing that because the kids keep me up. I get a chance to listen to them and while I’m able to pass something off to them, they in turn give me something, so it keeps me on my toes and my eyes and ears open to new things.”

After taking lessons from his father for about two years, his father suggested that he study with another teacher to get away from the father-son relationship. Bellson began with Bert Winans, one of the people to originate the first thirtee rudiments, and stayed with him for about six years.

“He was definitely a rudimental player,” Bellson recalled. “He knew I was going to dig into the set and play, but he wasn’t interested in that. He was purely a guy who would get your hands into shape for playing. In those days I had a parade drum with a gut snare and that’s the most difficult. You can’t make any mistakes and if you do, they come out loud and clear.” Advertisement

Completely ambidextrous, Bellson maintained, “One thing in the drummer’s favor I guess is to be able to manipulate the right hand or the left hand equally as well, and vice versa with the legs. I never had a chance to go out for sports because they kept me so busy in bands while I was in school, but the one thing I did really go out for was track. I was an exceptionally fast runner and my track coach, who was also the football coach, said I would be a great half-back, but I just couldn’t leave band to do that, so that took care of that. But I found out that when I did fool around with a football, I could kick with either foot, so I guess that is really a plus for a drummer. Today especially, we’re called upon to do some crazy things.”

After the six years with Bert Winans, Bellson learned of Roy Knapp in Chicago, with whom Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich had studied.

“He was sort of the papa of percussion in Chicago and my father asked if I would like to go up to study with him. At that time, I was 14 years old and they allowed me to join the union, which was unheard of because you couldn’t really join until you were 18. So, on the weekends, when I wasn’t playing, I would make a trip to Chicago, which was about 150 miles from Moline, and study with Roy Knapp and go see Tommy Thomas, or maybe Krupa would be at the Chicago Theatre or somebody was at the Hotel Sherman in the Panther Room, or maybe Charlie Barnett or Tommy Dorsey with Buddy. So, it was really exciting for me to spend the weekend up there. I did that for a few years, and not only did I study drums with Roy, but he extended the education my father had started on harmony and theory and got into mallets, playing xylophone, vibes and timpani, which I don’t have the chance to do much anymore.

“Without all that training, I’d really be out of luck today,” Bellson reiterated. “I think it’s wonderful for the young players today. They have some of the best books out, some of the greatest teachers and they have time and accessibility, not only on T.V., but in live performances, watching all these great per formers. So, any young guy today who wants to play, has no excuse. It’s up to him to say he wants to play and go ahead and do it and spend the time, be patient and really work hard. I can remember about 20 years ago, I was doing clinics around Steve Gadd’s area, Rochester, New York, and John Beck was his teacher at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester. In those days, when I did a clinic, I used to finish it off by inviting a drummer up from the audience to the other set of drums and we’d have a little battle. One day, John Beck asked me if I were still doing that, and when I said yes, he said he had just the guy for me. He told me about this young kid who could play anything Buddy or I could play, who played all the mallet instruments, had a keen ear for harmony, theory and writing, and I said, ‘I don’t want to know him,’ ” Bellson joked. “And it was Steve Gadd, and when Steve got up, I think he was about 18 at the time, I told him to start the tempo and he did, and I’ll tell you, he really made me sweat. I don’t know if he remembers this, but I told him later that if he really had eyes to make this his vocation, that he was going to be a tremendous player because he had everything going for him. Then a long period lapsed until all of a sudden, people were saying, ‘Hey, there’s a young guy in New York who came from Rochester and his name is Steve Gadd, and boy can he play!’ There again, you can see all the time this young man put in, and not only did he learn about drumming, but he learned the other percussion instruments and understands all phases of it and he can play every bag. He’s a wonderful barometer for the young player to use.” Advertisement

Throughout high school, Bellson continued with the school band, while taking lessons, and won the rudimental competition three years in a row and in 1941, he was finally convinced to enter the Gene Krupa contest.

“I was not contest minded in those days, and in fact, was very much against them. I felt that a contest was inaccurate in that maybe one guy was better than someone on a particular day, when the other guy wasn’t playing his best, and the fact that all the guys are good players and one had to be picked, I just didn’t like the idea. So, I declined the contest many times until I was talked into doing it. The local was very easy for me because there just weren’t a lot of drummers in Moline, but I started to get into it in the regionals. There were about 700 drummers in the Chicago area and many of them were really good. In fact, I was really surprised when they chose me as the winner. I had heard two or three guys who played there that played as good as I had, if not better. Winning that contest and getting to know Gene was really beautiful because he was a tremendous man and it was really an experience.”

All during high school, Bellson was the youngest member of a large horn band with five trumpets, four trombones, and five reeds, while he continuously listened to the records that came into his father’s store. Advertisement

“I was aware of all the bands that were coming into the picture like Benny Goodman, the Dorsey Brothers, Harry James, Duke Ellington and Count Basie, and they were definitely my influences. I was very fortunate to sit in with those guys when they came to town because I guess they heard about me because my friends would yell and scream, ‘Hey get my friend up there to play,’ ” Bellson smiled.

One such incident proved to be the turning point in Bellson’s career. When Ted Fio Rito’s band came into town, 17 year old Bellson sat in with the band and was offered a job right on the spot, since Fio Rito’s drummer was going to be leaving.

“I told him that I had three more months of high school to go, but when I graduated in June, if he still wanted me, I’d join him then, and he said fine, that he would be in California and I had the job. Sometimes people say things and they don’t live up to their promises, but he certainly did. When I graduated, I called him and he said he was ready for me, so I flew out to California with all my drums and everything.” Advertisement

The ensuing series of events were of great consequence to Bellson and are now an important part of musical history.

“My first job with them was at the Florentine Gardens on Hollywood Boulevard, in 1942. The big act on the bill was the Mills Brothers and they sort of took me on as their son. I had worked there for about three months, when during the last two weeks we were there, I got a little note saying, ‘Louie Bellson, please come and join us at our table,’ signed Freddie Goodman. So I went over to the table and he told me his brother was Benny Goodman and I started to stutter. He said, ‘I like the way you play and I would like to have you come down to the studio. Benny is doing a movie at Paramount Studios and would you like to come down and audition?’ I was so stunned that he had to tell me to sit down and take it easy. Well, I went down the next day and sat in with the Benny Goodman Sextet, played one number and Benny said I had the job.

“Now, I didn’t know what to do because here was Ted Fio Rito, who had taken me from my home and said to come out and made me aware of the Mills Brothers and had given me this wonderful job and was like a father to me. Now what was I going to say to him? Benny was leaving the next day and I had to just get up and go. So I took this up with the guys in the band and they said to go, that everybody doesn’t get the chance to play with Benny Goodman. In those days he was the King of Swing. Gene Krupa had just left, and for me to play in Gene’s spot in that great band at 17 years old was incredible! So the guys in the band said that I should go and they would explain it to Ted, and although I wanted to, I waited for Ted to cool down a little bit and then I called him and he was beautiful and just said that naturally he had been mad because he didn’t want to lose me, but he was happy for me.

“Of course, working with Benny at 17 years old, I can’t tell you what kind of feeling that was. I actually had to pinch myself every night, because there we were playing things like ‘Sing, Sing, Sing,’ and all the famous Benny Goodman tunes. He’s a rarity—a very unique human being and I must say that some of the greatest things I learned were with the Benny Goodman Band. For instance, at rehearsals, the rhythm section wouldn’t do anything. He would rehearse the five saxes alone and then the brass section alone, because he wanted those guys to be able to play any tempo and time without a rhythm section. He felt that you could have the greatest rhythm section in the world, but if you don’t have the instruments playing in time, then forget it, the band isn’t going to swing. He taught me how to really work in a rhythm section, be aware of the rhythm section and be aware of the band and play for the band. When it’s time to play a solo, then it’s your time to shine, but up until that point, you’re an accompaniment. The most important thing is to make that band swing. Solos are secondary. If you’re a great soloist and can’t swing the band, forget it! Now you’re good for five minutes a night and they have to hire another drummer to swing the band.” Advertisement

After about a year, Bellson’s stint with the Goodman Band was interrupted by Uncle Sam, and because of his past work experience, he was sent to Washington, D.C. to the Walter Reed Hospital Annex which had a large orchestra, a concert band and a jazz band. Their function was to play for all the amputees that came back from the war.

“It took me about two months to get adjusted to it,” Bellson recalled, solemnly, “It really flipped me out because all of a sudden I was seeing all these young guys coming in with two arms off, two legs and an arm off or two legs off. Then I started to worry that these guys, having been off at war and hearing those bombs, might be reminded of the bombs by my drums. But that’s all they wanted to hear and it was great. They kept me so busy there and they were so into music, symphony, jazz, small group, big band, that we’d play from 9:00 in the morning until 10:00 at night.”

After the war, as is apparent during any recession, people relied heavily on music and dancing as an inexpensive form of entertainment in which they could lose themselves and their problems. Dizzie Gillespie and Charlie Parker had pioneered be-bop and it became the primary music heard throughout the world. Advertisement

“Music was such a major part of people’s lives,” Bellson stated. “The only thing I’m sorry about today is that when I was brought up there wasn’t much T.V. and when you didn’t have that, you had the ballrooms and the theaters at which you could go listen to music or go see vaudeville. It’s a shame there aren’t a lot of theaters around today. It was such an education. Of course one thing the kids have today that we didn’t have, was music in the school systems, which is tremendous. We had a concert band and a marching band and that was it, and the music was limited. Today they have both those, plus a symphony orchestra, the big stage band and of course, they didn’t have jazz in the school system back in those days because they thought it was a dirty word. Now, because of the young people, they have found out that jazz is one of America’s only pure creative forms. But it’s funny how it has worked out, because we didn’t have any of that in school, but with all the theaters open, we were able to go out on the road. Today, even though music is built up in the schools, then they graduate and where do they go? That’s a big problem. There’s all this talent and there just aren’t the positions for it.”

After serving his three years in the Army, Bellson repeated his earlier pattern of three months with Ted Fio Rito before rejoining Benny Goodman for another year.

“When I went back with Ted in 1946 it was the first time I ever utilized the two bass drums. I had had the idea in 1938. I think one of the factors was coming from a musical family. My one sister, Mary, was an excellent tap dancer, so I had a certain amount of agility and the ambidexterity, and I sat down one day and thought, ‘How would it be to have another drum over there and still utilize the left hi-hat, but have another bass drum?’ So I drew this and got my diploma in art by making this design of the double bass drum set. Of course, in those days, when I first took it to various drum companies, they thought I was crazy. They weren’t really saying, ‘Get out of here kid,’ but they were saying, ‘Are you sure you want something like that, because that’s not really what the guys are doing.’ Finally, I had one built by Gretsch and I used it in 1946 when I joined Ted in San Diego.”

While Bellson didn’t use the double bass drums when he rejoined Benny Goodman, he began to once again when he joined Tommy Dorsey in 1947.

“When I joined Tommy, he made a big thing out of it because Tommy liked drummers. He had had Krupa, Buddy Rich and all these great drummers and he wanted a guy who could swing with the band and yet be a soloist. When he saw my two bass drum idea, he flipped out. He and I together came up with the idea of the revolving platform because most people would look and hear me play and say, ‘How can he do that with one foot? Where’s all that sound coming from?’ The minute Tommy would press the button and the platform would go around in the middle of the solo, people could understand. That was a wonderful musical gimmick, which we used later on in theaters and even one-nighters. Advertisement

“I always say that the three years with Tommy gave me some of the greatest training I had because he taught me how to use a lot of strength. Buddy worked with him too, and when I say strength, they’re always talking about Buddy and me today because of the tremendous facility to not only play solos with the band, but the ability to play one-nighters and play all night without getting tired. Buddy and I learned that from Tommy, because when you worked with Tommy Dorsey, you played from 9 to 12 without stopping, and then you ended up playing a half hour of overtime. You learned how to pace yourself, and either you learned it or went to the hospital and had to quit. In those days, we used to do 7, 8 or 9 shows during the days in the theaters. I remember one time we did six months of one-nighters straight without a day off and we averaged 500 miles a day. That meant you got on the bus after you played the gig, which ended at 1:30 and travelled with maybe a rest stop and a food stop. You got into the next town about noon and had some breakfast and then layed down for about four hours, got up, ate dinner, checked out and went to the gig. We did that for six months, and that’s what you call a tough gig.”

Bellson’s schedule today is not much less hectic, but between Tommy Dorsey and his father, Bellson now thrives on being constantly active.

“My dad taught me the psychology before I joined Tommy. He asked, ‘When you get up on the bandstand, what is one of the first things you think about?’ And I said, ‘Well, one of the first things I think about is what I have to do with the band.’ And he said, ‘No, when you get up on the bandstand, you should think about yourself first of all. If you watch athletes, you notice they first take a deep breath before starting their activities. They do that so they can concentrate and relax themselves, because unless you relax yourself, how can you do well on the job after that?’ It took a while for that to sink in, but he was right. Every time I had gone on the bandstand before my dad said that, I was nervous and I would off balance myself, but the minute that sunk in, it made sense so that I would have a foundation from which to work. My dad used to say, ‘If you’ve got 15 minutes and you think you want to write something, go ahead and do it, because that 8 bar thing may not happen again later on.’ So I learned the timing and pacing, so today, if I were to show you an itinerary, you would say it’s impossible.

“Aside from all the other things, I’ve always been sort of a health nut. I’m no angel, and I’ve had my share of eating the wrong foods and all of that, but I’ve never been a drinker, I don’t smoke and I’ve always felt that my body was important to keep in shape because of my work, and in order to function and do all these things, I had to keep myself straight. No matter how many times I decide to, say, do six months worth of gigs and that’s all, something always comes up. It’s hard enough just worrying about my band, but then Pearl will call me and ask me to jump in and help her out. Having done it for years, I’ve built up a lot of strength and I can actually go two days without any sleep and still play hard. Advertisement

“Another bit of information I always pass on at my clinics is that, say you have to play a club and you have two or three sets to play. It’s been common practice for years for the drummer to say, ‘Gee, I know I’ll be alright the first two sets, but I hope I don’t run out of gas on the third set.’ The third set is really the one where you really should have developed the strength and that should be the best one, actually. So psychologically, I make that one as good as my first two. I disregard the word hard—I take it out of my vocabulary.”

After three years with Tommy Dorsey, Bellson turned in his notice. As he explained to Dorsey, he was not unhappy, but wanted to return to California to further his studies with Buddy Baker, who is still his teacher today. He also had the opportunity to join Harry James, who was just working weekends on the west coast, which would perfectly afford him the time to study.

Bellson had been with Harry James for about a year, when one day, trombonist, Juan Tizol, with whom Bellson had been staying, approached him with the news that he had just spoken to Duke Ellington, who had asked if Bellson, Willie Smith (lead alto sax) and Tizol, himself, would like to join the Ellington band. Advertisement

“I thought, ‘My God, what will Harry James say about losing three of his players?’ But Harry was beautiful and felt that everybody doesn’t get the chance to play with Duke, so the three of us joined Duke in 1951.

“Of course, I needn’t tell you want an experience that was! With Ellington, it was all the other things that happened in the other bands, but you had to go a little further with that band because they did things like play with symphony orchestras, which other bands didn’t do. We played with Toscanini’s NBC orchestra with Duke’s band right in the middle, and I was in on the first of the sacred concerts with Duke. The first one was at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, and I remember Duke came to me and said, ‘Okay, you’re going to play a drum solo in church tomorrow. I know you’re bewildered, but just think about it.’ So the next day, he came up to me and explained further, ‘You know, the music is based on “In the beginning —God,” which is from the Bible, of course, and as you know, in the beginning, there was lightning and thunder, and that’s you.’ Then I knew what to do. That’s how Ellington was. He hit me with the drum solo first, then the next day he was saying, ‘Here, let me teach you.’ Then I knew what to do once I knew the role I had to play.

“Many years before I joined Ellington, he and Strayhorn (Billy) were admired by all the great composers and arrangers like Dave Rose and Quincy Jones, and they couldn’t figure out how Duke and Strayhorn voiced the saxophones, how they voiced the brass, because they had their own key ways of doing it and they wouldn’t let anybody in on this. When I first joined the band, I roomed with Strayhorn for a while and one day I finally asked him to teach me and tell me how he did that. As soon as I had asked, I realized that I shouldn’t have by the way Strayhorn looked at me. I apologized and said that I realized I shouldn’t have asked; that it was a private thing between him and Duke. I used to get to the gigs early, though, and one day, after I had been with the band for about six months, Duke was there early as well, and he motioned for me to come and sit by him at the piano. I did, and he hit a chord and said, ‘See this? That is what I used on “Caravan.” And he explained who each note went to and he spelled the whole thing out to me. He showed me things for about a half an hour and he said he had never shown anybody else. I just sat there and cried. Here I was, little me in the band, and he was showing me all this stuff that he and Strayhorn did, which you can’t see in books and only comes from them. I never forgot that.” Advertisement

Ellington also gave Bellson his first writing opportunity.

“When I had first joined the band, he said that he understood that I was an arranger and I said, ‘Well, not really.’ And he said he wanted me to bring in a couple of my scores and I said, ‘You want me to bring in my scores? No, I couldn’t.’ After all the things he and Strayhorn had written, I couldn’t bring him mine. It took him about two weeks of coaxing to get me to bring in two charts. The first thing I brought in was a thing called “The Hawk Talks,” which he recorded and became a big jazz hit. A lot of people think that was written to commemorate Coleman Hawkins, because he was known as the Hawk, but Harry James was also known as the Hawk and I wrote it for Harry. Then “Skin Deep” was the drum solo which I also wrote and gave Duke, which he also recorded. For that band to record two of my things was just incredible!”

Bellson’s writing was initially prompted by his father at a very early age.

“Dad felt that by the time I was 10 years old, I should have all the training possible. He said, ‘Look—you’re doing great musically as a drummer, but now let’s get into some melodic instruments and let me start you on a little piano and some harmony and theory.’ I told him I didn’t want the piano, but he insisted and I went ahead with it, and the minute after my sixth lesson, I was after my father like a vacuum. I couldn’t get enough of it. Then he got me into writing two part harmony and three part harmony, writing for a string quartet, big groups, small groups.

“In 1947, when I joined Tommy’s band, Marty Berman and I were driving out to the gig one night and a song came on the radio by Herb Jeffries, a singer in Duke Ellington’s band at one time, and this album was with a beautiful string orchestra and the radio announced that Buddy Baker wrote all the arrangements. I told Marty that I sure would like to study with this Buddy Baker person, and Marty said, ‘I know him.’ So I was introduced to Buddy and he’s been my teacher ever since.” Advertisement

Bellson and Baker also collaborate quite a bit, in addition to Bellson’s most often collaborator, Jack Hayes.

“He may start a tune and get halfway through it and then give it to me to finish,” explained Bellson. “Or vice versa. Sometimes we’ll do the whole thing together, composing and arranging, and other times, I’ve completed the whole composition and then give it to Jack to do the arranging, or vice versa.”

Juan Tizol was not only instrumental in getting Bellson together with Ellington, but also in getting Bellson together with his wife of 28 years, Pearl Bailey.

“Pearl would stay at the Tizol’s house when she was in California and I’d be back east, and when I was in California, I stayed in that room and she’d be away. They used to always ask me if I had met Pearl Bailey and I’d say that I heard about her, but never met her, and they used to ask her if she had ever met Louie Bellson, and so they’re the ones that really got us together in a sense. We didn’t meet at their house, but we finally met in Washington, D.C. at the Howard Theatre. I was with Ellington and four days later, we got married. We were married in London because she was working there and I had two weeks off, so I just flew over to where she was.

“Like Pearl says, we did it when it wasn’t fashionable,” Bellson laughed. “When we first got married we got a few letters from some people who came up with some nice names,” he confided of their marriage which took place at quite a racially prejudiced time. “But for the amount of letters we got like that, there were 9 million in favor. I would say that the fact that Pearl was Pearl, more so than me because she had a bigger name, and still does, helped as far as being able to go to different places, because I felt that if we were not celebrities, we would have had a little difficulty going into certain places at the time. Thank God it isn’t as much of a problem today, but it’s because of the young people who have learned to grow up and respect one another no matter who or what you are.” Advertisement

The press clamored for interviews, but Bellson and Bailey became very selective about those to whom they would speak. More than willing to discuss their musical projects and careers, they granted some, but even that backfired more than once.

“I gave one guy an interview and he twisted everything around and the article which finally came out was ‘What I Know About The Negros, by Louie Bellson.’ We hadn’t even discussed that at all,” Bellson recalled, explaining that a lawsuit ensued, for which they were monetarily compensated.

Two children are the products of their marriage, and Bellson admitted that while Tony, age 26, and Dee Dee, 20, have certainly had to battle the children of celebrity parents syndrome, they are both extremely well-adjusted. Advertisement

“I’m sure it must have been difficult growing up around celebrities. I’m sure there is a pressure on them because they have to try to live up to something, and maybe while Tony wants to play drums, he feels he has to live up to something. Just like Frank Sinatra, Jr. I feel he has a lot of talent, but he’s constantly compared to Pop and Pop is Pop,” Bellson said, adding that he is perfectly comfortable with the fact that both his children may end up in show business.

Shortly after his marriage, Bellson left Ellington, with whom he had been for about two years, and began his own band, which performed both with his wife and separately.

“I think one of the main factors that kept Pearl and me together was that we realized that each one of us had his own career and yet we were able to work together quite a bit too. Otherwise, she would be going off in one direction and I would be going in another and it never works if you don’t see one another for three or four months at a time.”

Bellson has had his own band ever since, and is very excited about his current group.

“I feel like our band is so hot now. We just finished a European tour and it was the first time I had been over to Europe with my own group. It looks like we’re going to be going over once a year now, for at least a month, and it also looks like we may be going over to Japan also. We’re going to keep it going over here in the States too, and I’ll be confining three quarters of my time to the big band.” Advertisement

Bellson’s association with Slingerland began around 1936, but because of a series of events, he has only been back with them exclusively for the past three years.

“I had a Slingerland set when I joined Benny, and the reason I switched over to Gretsch was that Benny had a contract with them. I didn’t realize at the time that I could have walked up to Benny and said that I use Slingerland and he wouldn’t have minded, but they supplied him with drums and I felt that in order to keep my job, I had to use Gretsch. From Gretsch I went to Rogers, from there I went with the Pearl Company, and now Slingerland again. I must say this, all those companies were very wonderful and I had a good standing with all of those people.”

To Bellson, a good drum set is one made of good wood. While he used to use the fiberglass shells, now he feels that the wood is the most natural sounding.

His commonly used set-up for when he plays with his big band, consists of two 24″ bass drums, one 9″ x 13″ tom in the middle of the two bass drums, the Spitfire snare drum, which he designed for Slingerland, two floor toms, 16″ x 16″, with the one in the back tuned slightly lower, a 14″ pedal Roto tom by his hi hat, and on his right, next to his two floor toms, he uses 14″ and 16″ regular Roto toms, which he turns manually.

“The very first set that I got had a bass drum, a snare drum, a small tom tom and a big tom tom with two cymbals and a hihat. Buddy said in his interview with Modern Drummer that he challenges the fact that some guys have too many drums and I agree with him. If you join a group like Chick Corea, however, where he wants to hear three or four concert toms because of the sophistication of the music, then you have to add that. Of course I’ve added quite a bit, but what I’m against is guys having maybe 25 drums which they don’t play and are just for show.” Advertisement

While the above mentioned set-up is his most common, Bellson conforms his needs for a particular event, sometimes finding himself utilizing only one bass drum, while occasionally, he uses his triple drum concept.

“The concept stemmed from the use of the two bass drums, and I went further because I felt that I wanted to utilize more sounds with the tom toms and Roto toms and more snare drum sounds ranging from the piccolo to the bigger snare drum and I wanted that same idea with the bass drums. In order to get those various sounds, I had to go with different size drums. I use that set only when I’m doing a thing I wrote called “Bittersweet” with a symphony orchestra. I use two mallets in each hand as well as five pedals and three bass drums. I can oper ate all three bass drums with three pedals alongside of the middle bass drum, but I would only use it for that particular piece. I would never use all of that with my big band—I don’t need it.”

He even has an entire Roto set which he has used occasionally.

“When I went to Remo when he first started the Roto tom idea and asked him to make me a. Roto set, he thought I was crazy. I had him make me two bass drums that are set up like Roto toms so I can actually play the bass drum with the pedal, which stays stationary, and I can turn that drum and it will rotate and I can get various degrees of an octave range with each bass drum. Then I have all the Roto toms he made—6″, 8″, 10″, 12″, 14″, 16″ and 18″ and he also made me a Roto snare drum, which means I can turn it to the right and get a piccolo sound or turn it to the left for a deeper sound. You can actually get tonality with that set because those Roto toms have been the closest drums to getting a perfect pitch.” Advertisement

Bellson uses the Remo Fiberskyn 2, which he says looks exactly like the old calfskin heads and have a mellow, round sound.

He uses a Slingerland stick, which he designed and says is comparable to a 5A. “A lot of people feel that they need a heavier stick to get a bigger sound, but that’s not necessary. The work comes from the player and if you get a good middle weight stick, then the rest has got to come from you.”

His cymbals are all Zildjian and typically, he uses a 20″ pang cymbal on the right of the right bass drum, an 18″ or 19″ on the left of the left bass drum, with four rivets. Underneath one of the crash cymbals on the right, he has a 22″ swish cymbal. On stands on either side, he uses an 18″ medium crash and then 14″ hi-hats. More recently, he has been using the Quick Beats, because, as he explains, “The bottom cymbal has four holes about 1/2 inch around the perimeter so that when you utilize the foot cymbal with your foot, you always hear a chic sound and you don’t get that airlock initially.”

Bellson is far from a traditionalist, in that he is open to and willing to experiment with anything.

“I think the electronic equipment is marvellous, but I think we’re still in the infancy stage as far as drums are concerned. Syndrum is a marvellous invention, but I think with the electric drum set, so far, we haven’t really come to it yet. I think Syndrum has come the closest, but I feel that in the coming years, we’re going to see a lot of interesting things happen, and when they do get it together, it’s bound to be very good. Advertisement

“I always change. I don’t like to keep doing the same thing. I do that with my playing. I like to forge ahead. Sure, there are some things that are going to stay constant and good all the time like Count Basie. He could be 9,000 years old, he’s always going to be a great musician and a loveable character. With me, as a drummer, I just feel that there are so many new things that are always happening and that’s the way my life is structured. I’ll keep on doing some of the things, but all the newness is the idea of excitement to me.”

Last year’s big excitement was the reenactment of Slingerland’s National Drum Contest.

“From the experience of the Krupa contest, I sat down with Larry Linkin, the president of Slingerland, and told him some of the pluses and minuses of the contest. In the Krupa contest, we had to play along with his record of “Drum Boogie” and of course, all

through that record, you could really hear the power of Gene. For another drummer to sit down at a set of drums and play with Gene playing on the record was difficult. The idea was to play along with that record without missing a beat. So, I decided to make a record with my band without me and then have the player supply the rhythm. That way, he wouldn’t have to listen to me and he could put on a headset and play like he was playing in my band. One of the other things we felt that we needed to do was to make sure the four finalists would be able to play with my band, because they would have been playing with the record up to that point. We also wanted to make sure that at the local, regional and semifinals, we had competent drum teachers and players as judges, which unfortunately, we didn’t have with Gene.

“We tried to look at each player and what they did with the band and how they played the number and backed up a solo, what they did in ensemble, how they blended in with the rhythm section and then their solo and the continuity and what kind of story it told. Years ago, we said you had to start the solo, then have a quiet part and then wind up bombastic like. Today it is a lot more open. I’ve seen guys end a solo really quiet and it’s tremendous. As long as they’re able to communicate that story over to the audience, it’s a good solo. Advertisement

“All the guys were great players. Each one of the 13 semi-finalists could have been the first place winner. I’ve been very pleased, though, because I found out that not only has the winner benefitted from the contest, but many of the 13 semi-finalists have already been getting gigs. I was really happy to give some young guy a shot like I had,” he smiled.

With his busy schedule, it would be very easy for Bellson to not stay actively concerned about young drummers, but that is far from the case.

“People have been nice to me throughout the years, and I can’t forget that. To me, the young kids, like our next door neighbor who is a drummer, Dave Black, are the future, and you’ve got to pass along some things that will help them out so they can, in turn, help somebody else out. I enjoy doing it.

“I think every drummer should do what this young man, Dave, has done and is doing, and that is not just being content with getting a set of drums. If you make up your mind that you really want to get into it, then I think it’s important to take advantage of the high schools and the colleges, because these guys are getting so much knowledge. I know Dave has access to playing with an exceptional band at the California State University at Northridge, and not only that, but getting into percussion and he’s writing and composing. Then when you do get on your own, you’ve got something to work with. Advertisement

“I’m doing some thing I love doing, so therefore, it doesn’t become a job,” he concluded. “It’s a lot of work, but it’s pleasant work.”