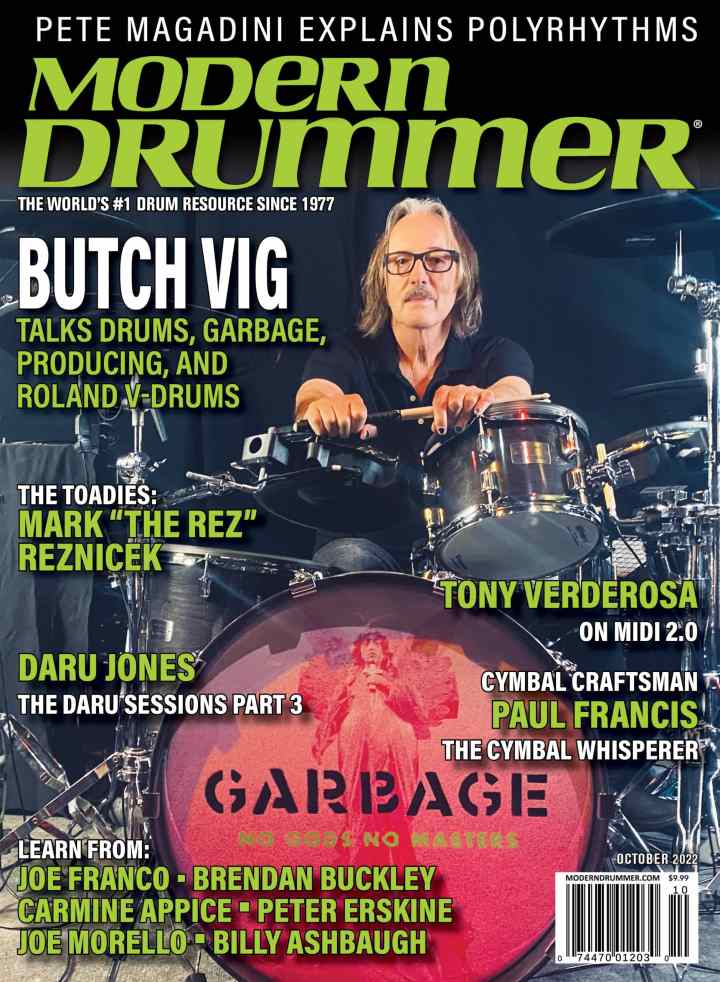

Pioneering Drummer and Producer Butch Vig Talks Drumming, Roland V-Drums, Production, and Garbage.

There are very few musicians that have had the influence that Butch Vig has had on modern rock music. As a drummer for the band Garbage his acoustic-electronic-hybrid approach to drumming is revolutionary. Their new record No Gods No Masters is their best yet. Providing a sonic landscape that supports strong and introspective lyrics, all laying on top of multiple layers of rhythm and groove. His side project bands 5 Billion In Diamonds and The Emperors of Wyoming are about as original as music can get. 5 Billion In Diamonds creates big sweeping soundscapes, combined with quirky and glitchy grooves. The Emperors of Wyoming puts a new twist on country music by combining it with Vig’s electronica influenced drumming.

As a producer, Vig’s credits stand for themselves. Killdozer Twelve Point Buck; Nirvana Nevermind; Smashing Pumpkins Gish and Siamese Dream; Sonic Youth Dirty, Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star; Against Me! White Crosses; Helmet Betty; Soul Asylum Let Your Dim Light Shine; Jimmy Eat World Chase this Light; Green Day 21st Century Breakdown; Foo Fighters Wasting Light and Sonic Highways; Sound City Real to Reel, Silversun Pickups Widows Weeds, and Physical Thrills and many, many, others. He has also worked on remixes and singles for bands such as U2, Alanis Morrisette, Muse, The Cult, Beck, Korn, Limp Bizkit, Nine Inch Nails, and many more!

Modern Drummer was lucky enough to sit down and talk with Butch about his new involvement with Roland V-Drums, his drumming in Garbage, his side projects, drummers, and his amazing career of producing legendary records. For anyone interested in today’s rock music, drumming in an influential band, electronics, working with a producer, and music production, this will be a very exciting read. Advertisement

As an addition, Butch brought along members of Roland’s artist relations and channel strategy teams, Igor Len and James Peterscak, who contributed with Butch and others on the Roland R&D team to the development of the brand-new Roland TD-50X module, the new V-Drums Acoustic Design hi-hat cymbal pads, and other new drum products. Butch was integral in designing the new software and hardware for the series, and since he worked closely with Roland, it felt natural to involve them in our conversation.

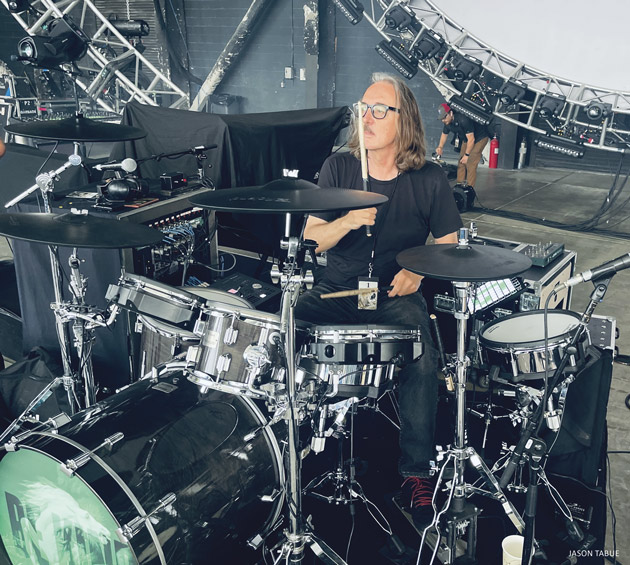

MD: Let’s start with the most recent change in your drumming. Garbage has been touring with Tears for Fears, and I saw a show and was floored to see you playing all electronic drums and cymbals on stage. Why, and how did that happen?

BV: Garbage has always been a “techie” band. There is a lot of layering, processing, and electronica on all of the Garbage albums. When we first toured in ‘95 and ‘96, I played an acoustic kit that was triggering samples and sounds from the records. Triggering was sort of a mess back then; I was using ddrum electronics. As we started to tour extensively, I began to rely more and more on triggering electronic sounds and less on the acoustic kit. Eventually, maybe 2017 or ‘18, I went all electronic and dove into the Roland TD-50. Today, there is no looking back with the TD-50X and V-Drums Acoustic Design series. Advertisement

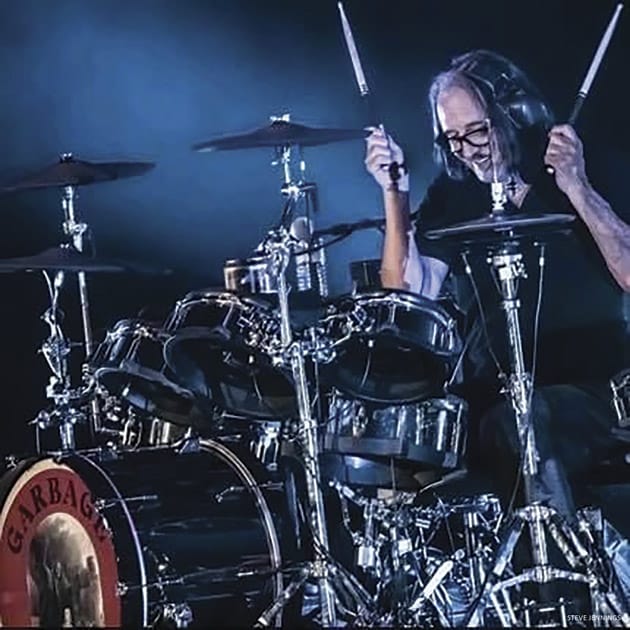

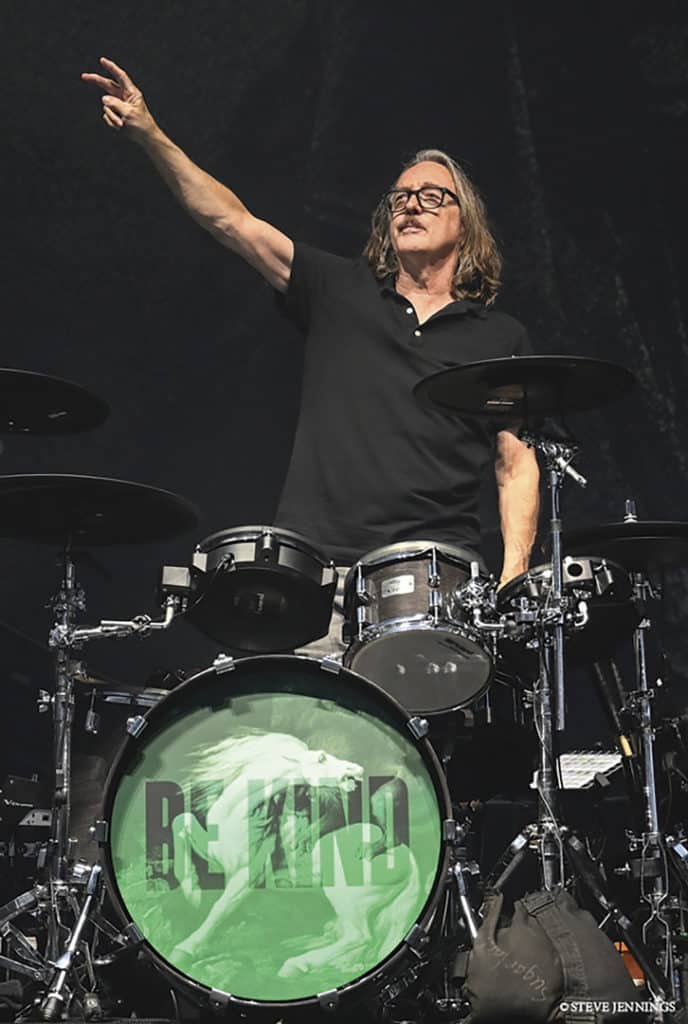

Sonically, I love what I can do with V-Drums, and the band loves them too. Shirley Manson (the singer for Garbage) can walk right next to my drums and not be assaulted by the crashing and banging of drums and cymbals in mid-flight. That aspect gives the band members on stage more freedom to move around without having to worry about ambient sound. If you stand side stage at a Garbage show, it’s dead quiet. Everything is going direct to the front of house, we are all using in-ears, and there are no amps on stage. Our front of house engineer David Guame feels like he’s mixing in a studio because there is no ambience from the venue that he has to worry about.

MD: That can be a blessing and a curse sound-wise. Why the switch from ddrum to Roland?

BV: I will admit there was a bit of a learning curve when I made the switch. I didn’t know the software, so when I started layering samples, doing editing, using internal compression and EQ, I was a little slow. But playing them was pretty easy, I really like the Roland pad’s feel.

Truthfully, I did have issues with the first versions of the hi-hat, and Igor can tell you all about that. I really complained to him a lot. (Ha!) But now I feel that the V-Drums are really dialed in and an integral part of the Garbage sound live. Advertisement

MD: How did the hi-hat pads change?

BV: They track much better now. Initially, for a rock drummer (like me) who keeps eighth or sixteenth notes on the hats and ride cymbal, they just didn’t have the sensitivity. When I was playing dynamically, they just didn’t track my dynamics well. But they have finally nailed that. I was very self-conscious about the hi-hats on the first tour, making sure that tracked correctly. With the new hi-hats, I can play very expressively now, and I don’t even think about them as an instrument. I just play.

MD: So Igor, what actually changed to make the hi-hat and ride pads better?

Igor Len: The new hi-hat followed the design of the new ride cymbal and how it works. When Roland upgraded the design of the ride cymbal pad, we were aware that as you play different sections of the ride cymbal, the timbre according to placement is different as well. When you go from the edge to the middle, and up to the bell, the sound of the cymbal changes significantly. So, the first thing we addressed was the ride cymbal. We used a continuous sensor that is not sectional. Truthfully, that is why the cabling had to change from tip ring sleeve to USB. There is so much information flowing out of the trigger to the brain that there is no way to use a tip ring sleeve cable anymore.

There were a few drummers who were instrumental in having the hi-hat change thanks to their feedback, and Butch was one of the guys who commented in detail about it initially. So now the cymbal pads have been taken to a different level. Advertisement

MD: What are you using as a brain with your V-Drums?

BV: I have the latest software upgrade in my original TD-50 (the TD-50X module upgrade), I have my 4-piece set, the VAD706, with kick, snare, rack, floor, and cymbals. Then I have a TD-50 mesh pad on the left that provides me alternate snare sounds for verses or bridges. The other two pads are triggering sound effects and loops. I have some weird distorted keyboard drops, sub bass drops, and distorted drum fills and loops that I trigger for different songs. I have an Ableton Launch pad on stage, so when we start a song, I trigger the changes for all of the sounds and MIDI information for each song from that pad. When I glance at my TD-50, and I see the name of the song, I know everything is ok.

MD: You are the one making all of those changes on stage? That’s a lot of responsibility.

BV: Yes. The Ableton pad goes to a laptop, that laptop does the MIDI changes for the drums, bass, guitars, and keyboards. About 90% of the Garbage songs have a sequence, a loop, or a click on stage. But many of those are tempo mapped where the tempo changes during the song. In this last tour all of the songs except one had some sort of a sequence, loop, or click. When we do our own tours, we will often do a bunch of stripped-down songs in the middle or at the end where we freestyle without the click. That really keeps us on our toes.

MD: What click sounds do you use?

BV: I don’t like the beeps and ticking of normal click sounds. As a drummer listening to that type of click, even if you are off incrementally, you hear the flam between you and the click, and I hate that. You’d laugh if you heard my headphone mix. I have clap sounds, tambourines, and shaker sounds all mixed together. Those sounds are more forgiving, and you can move the time around the click a little more. It really is OK if the drums move around a little bit. I also use that approach in the studio. I don’t like using regular click sounds as a producer. I actually have an older Roland drum machine that I will use the shaker and tambourine sounds as a click when tracking a song in the studio. I also have a loop of the shaker and tambourine from the song “Stupid Girl” from our first record, and I can speed that up or slow it down. I like playing to that loop, I find it to be easier to play with, and (like I said) more forgiving. Advertisement

MD: How long did it take you to get used to using V-Drums live?

BV: When I used them on the first tour, I was hitting them too hard for the first month. I like to play dynamically, and I hadn’t set the dynamic range on the snare, so I was pounding away. But once I adjusted the dynamics it was pretty natural. It probably took about a month to get into that mindset. I like the pads, they have always felt really good. It was really the hi-hat that I bitched and moaned about, but that’s all in the past now.

MD: Do you, or have you, altered your playing for the pads?

BV: I have found that when I’m not playing as hard, I can play more “technically” and be more precise.

MD: What did you dial in to use them on this tour?

BV: I started by taking the Roland preset kits that I liked, and I went inside and fine-tuned each one of them. I dialed in each sound separately, piece by piece. Then I loaded my own sounds and custom samples. I have a bunch of sub-kicks that I like. I have some custom snare samples that I use on different songs. Then I layered the Roland sounds and my custom samples for each kit and each song. I spent some time dialing in the percentage of my own samples vs. Roland sounds for each kit. Then I added some effects, bass drops, and alt. snares for my auxiliary pads.

MD: When you are blending your samples and the Roland sounds live, what is the ratio between the sounds that we hear out front when we hear Garbage live?

BV: It’s always a blend. On the mellower songs, and the harder rock tunes, I’m probably using about 70% Roland sounds, and on the more electronica and techno sounding tunes I am using about 70% of my own sample sounds. It all depends on the song, whether I want it to sound more organic, or more electronic. Sometimes I’ll blend the two sounds 50/50, it all depends on the song. Advertisement

There was an initial learning curve because I didn’t know the software, but not everything (in life) can be “drag and drop.” After a little while I got really fast at the Roland TD-50X software. I keep a set here at home, so I can work on the sounds, or just bash away and it doesn’t drive my wife nuts. For the 2022 tour, by the time we went into rehearsal and pre-production with our production manager, Billy Bush, and our front of house guy, David Guame, everything was preset and ready to go.

MD: Do you remember what of the Roland sounds that you are using?

BV: There are an overwhelming amount of sounds in the TD-50X, which is great for me because I love to have options. Roland has really upped their game in terms of sonics. The sounds are gorgeous, and they are very expressive and dynamic. There are also a lot of different velocity layers so you can really play dynamically, and it sounds very natural.

That’s probably an important point for drummers who aren’t as “techie” as me. Drummers rely on sounds that are expressive and as real as possible, and that’s really what these sounds are.

MD: Let me ask the Roland guys James and Igor, where the new sounds came from?

IL: I know Butch suffered through getting all of the new sounds and having to reprogram all of his kits, and he wasn’t very happy about that. (laughing)

BV: But it was worth it! I’m a gearhead, so I just poured a big cup of coffee and powered through.

MD: Caffeinated gearhead tunnel vision.

BV: You bet. But by 5pm I had probably progressed to a nice glass of vino! (laughing)

James Peterscak: The TD-50X module is an important upgrade because it came out with the new Roland VH-14D hi-hats that Butch was speaking about, which come standard in Roland’s new VAD706 kit and can also be purchased separately. With those new hi-hat pads came a host of new capabilities that needed new sounds. Because of the new technology in the hi-hat pads, we had to develop a new way that we captured hi-hat samples. The way that we captured those sounds opened the door to new possibilities and new levels of expression. Once we did that with the hi-hat sounds, we went ahead and did the same thing with all of the cymbal sounds. Advertisement

The TD-50 has been out for about six years, so we took the opportunity to do an entire sound upgrade. With all of that work, we were able to create a new kind of ambience feature that allows users to dial in the ambience of each sound. This is similar to our V-Editing feature. The room that a drum is in becomes as much a part of the sound as the drum itself. The room is such an important part of a drum sound. Therefore we developed a way to dial in the room sound through what we call Pure/Acoustic Ambience technology. Now people can dial in the room sound along with the drum sound. That opens a whole new door creatively. It becomes a whole new environment in which to create drum sounds.

IL: That is why we call the TD-50X an upgrade not an update. There is a big difference between those two words. The core of the sounds is new, the source of the sounds is new. Unfortunately, you can’t take your old sounds and sets and transfer them to the new module. That is what Butch was dealing with, and truthfully what may disappoint some people. But, believe me, the change is worth it, and as a proof to that we have gotten so much positive response from the drummers that we have been working with, that we know the upgrade is worthwhile. All TD-50 owners and players can upgrade their module to the TD-50X through our Roland Cloud platform.

In the end, it’s obvious that everything has improved, and the bar has been raised. That’s why it’s all about the TD-50X going forward.

JP: We try to have the Roland modules talk drums. When a drummer wants to customize sounds, we have made that process work in the way that drummers are used to. Most drummers don’t talk in technical language of sound synthesis. Drummers think in terms of larger cymbals and smaller cymbals, deeper snares, and larger or smaller toms. That’s how drummers think about drum sounds. So that’s how we designed the new sounds and samples. Therefore, Butch’s new kit is a truly hybrid kit with the VAD706 at its core, along with the TD-50X and the new cymbal pads.

BV: As a record producer, the sound of the drums in a room defines the vibe of the song. If you are in a ‘70s sounding dead studio, that room and studio will define the vibe of the music. If you are in a big room that is creating that “big room” sound, your brain interprets that, and it influences the music. When you are recording drums, the decisions of how the room is going to help create the vibe of the track are important. The new V-Drums software allows you to tailor make, and really create a specific drum sound. For example, you can dial in the overheads on the cymbals, but keep the toms dry, all while making the snare sound really wet. There is an incredible amount of flexibility and control in creating the drum kit sound that you want. Advertisement

I especially like V-Drums for live venues. Because there are no drum mics on stage, I am really creating the room sound that I want within the TD-50X. Obviously, my drum sounds are going through the PA and the front of house engineer is going to treat my drum sound as well. But now I can create a much more complete drum sound from the stage.

MD: When you use them live, what are you sending the front of house from stage?

BV: We send the kick, snare, and the toms to individual outputs, the hats and cymbals also get a separate send to the front of house, and the three aux tracks are mixed together in a stereo output. I create a submix from stage and that is what he gets out front. We were initially going to create a single stereo mix to send out front, but in big amphitheaters the low end was creating some problems, and he was having a hard time getting a grasp of the low end from the super subs in the drum sounds, especially on the kick sound. We decided it would be helpful to create separate outputs, so David (FOH) has a lot of control.

MD: How about blending the acoustic sounds and the TD-50X sounds live?

BV: I default to the Roland sounds, and then I slowly bring in my own custom samples. A lot of my samples are really processed. They are often heavily compressed, run through distortion boxes, and heavily EQ’ed. I have samples that are 8-bit crunchers and are created to dirty the sounds up and make them more glitchy. I have a bunch of snare sounds that are like intense gunshots, so you don’t have to mix in too much of those sounds to make a big difference. Live, I don’t use many of the reverbs or delays that are in the TD-50X, because front of house can add that as necessary. When I am recording the TD-50X, I use all of the onboard reverb, compression, and delays. Live, I leave that up to front of house. However, I do use the EQ and compression from the TD-50X live. Advertisement

The kits that I have created are for specific songs, but I have a bunch of other kits that are just crazy sounding. During sound checks I load up one of those kits and Eric Avery and I start playing this bizarre dub jam. I’m sure everyone who’s listening wonders what the hell is going on. Then when Shirley walks on stage, I can change to one of the Garbage kits and we can get down to business.

IL: In today’s live music it is about bringing the studio sound to the stage. I work with a lot of bands and music directors of pop acts like Justin Bieber and Doja Cat, for example. And everyone is determined to bring their studio tracks with layers and layers of samples and sophisticated processing to play live. The TD-50X is a very liberating instrument, as it enables artists to do exactly that, bring the final studio drum sound production familiar to all fans of the album onto the stage and stay true to original version of the song.

It’s been a long road. Looking back, I remember the Simmons drums, then the arrival of the ddrums, and then electronic drums became something that you could use to practice on backstage or at home without disturbing anyone. That is all good. But V-Drums and especially the new V-Drums Acoustic Design series are a whole new ballgame. They are an instrument unto themselves and designed to be a live-ready solution for touring drummers, no matter the musical genre or level of the player. Advertisement

MD: Butch, how have you viewed the transformation and evolution of electronic drums?

BV: I cut my teeth playing rock drums when I was 16-years-old in my high school band Eclipse, I was in a band called Spooner, then a band called Firetown that got signed to Atlantic. I had a Yamaha and Ludwig kit that I used to play live with a bunch of different snare drums. Initially that’s how I was approaching the records that I played on and the records that I produced. I’m a drummer, when I was recording, I would get obsessed with acoustic snare drum and kick drum sounds and spend hours tweaking them to get that perfect drum sound like everyone else.

When we made the first Garbage record, I approached it differently. We started using samples and loops and really processing everything that we recorded in the studio. At first, I had no intention of touring with Garbage. But when we toured for the first time, we wanted to take the studio on the road, like Igor said. Back then it was a daunting task and kind of a big mess. We were using ADAT players to play loops, but that meant we had to fast forward or rewind between songs.

Then, I got the ddrum 2 because they were resilient (road-worthy), and the trigger was pretty fast. I actually went into my studio in Wisconsin and tried to measure the response of the trigger time. You could load your own custom 8 or 12 bit mono samples into the ddrum, it was crude but it worked. For that tour we mic’ed the entire kit, and had the ddrum triggers that we blended with the acoustic sound. It was a complicated process, we had a lot of front of house guys that didn’t like it, and they bitched and moaned about it. There were phasing issues with the samples and the acoustic sounds, and there were issues because we didn’t have in-ears and we had wedges on stage. I can’t blame our FOH engineers for complaining! Advertisement

Eventually we went to in-ears on stage, and that helped a lot. We didn’t have as many mics on stage for the second tour. We mic’ed the kick and snare and had two overheads, the toms were just triggered sounds from the ddrum 2, that simplicity in mic-ing, and the simplicity of my smaller kit helped a lot.

On that tour we also started putting the plexiglass shield around the drums to deal with some of the cymbal wash. It helped with leakage, but it also reflected and pointed all of the cymbal sound right back at me. It was so loud that I couldn’t take it. I had to turn my in-ears up so loud just to deal with the reflected sound of the cymbals that I started getting worried about my ears. We stayed with that set-up for the Beautiful Garbage and Bleed Like Me tours, and then we took a long hiatus.

We came back with Not Your Kind of People in 2012, and so much had happened in music technology in the eight years that we took off. We did an entire rethink of everything. When the Roland TD-50 came out, I had been waiting for it for a long time, and I dove right in. Like I said, there was a bit of a learning curve, but the band loved it right away. And now there is no going back! Advertisement

JP: The modern drummer has a new job, we are no longer “just” the drummer. So much of our job has to do with triggering loops and backing tracks. That is what is expected of us today. Butch has been a pioneer in this, and that is such a big part of what he does in Garbage. However, not all younger drummers are coming at this “new world” from the realm of a producer (like Butch.) What would you tell young drummers to help them deal with this new “job description” Butch?

BV: That’s a great question. It’s a totally new and brave new musical world. Artists approach drums and rhythm tracks in a completely different way from how they used to. For young drummers it has to start with the technical skills. How to PLAY the drums. You have to learn the craft of drumming for whatever style or approach that you are playing. That might be rock, hip hop, jazz, or whatever. But so many young drummers have to understand that a majority of modern drum sounds these days are not only the sound of the acoustic drums. There is A LOT of manipulation going on: loops, production, EFX processing, etc.

When Garbage plays a festival, I do a quick check on my kit, then I like to walk around backstage and see all of the different drum sets. I’m a gearhead, I like to see what kits drummers are playing, I find it fascinating. And what I have seen is that “drum sets” today are all over the place and totally unique. Some have only acoustic drums, some have triggers, some have triggers and pads… But the bigger the shows get, the more the drummer is supplementing their acoustic drums with modern technology! The sound of modern music has evolved so much in the last 20 years. Unfortunately, I don’t know of any place that young drummers can learn about that stuff. I’m sure there are some basic tutorials online, but it takes more than that. Advertisement

MD: That is why Modern Drummer started our Creative Percussion Controllers (electronic and hybrid drumming) column with Tony Verderosa, to address exactly that very issue.

BV: Today the approach to being a studio or a touring drummer are one in the same. That is because whether you are recording or touring, drummers have to deal with all of these different aspects of technology and drumming that James just described.

IL: In the time that we (Roland) have been working on the new triggers and pads, I have talked to Jim Keltner, and no one has a better studio drummer perspective than Jim. He posed a good observation when he said, “Why is everyone looking at electronic drums as an attempt at replacing the acoustic drums. Electronic drums are their own instrument. Drummers play on stage for the whole gig on the same kit while the guitar player is changing guitars and stomping on pedals constantly. Keyboard players also change sounds many times during every song! Gimme something so I can have some variety on my kit too! If something creates good sounds, I want to use it!” We wanted to create an instrument that is going to inspire musicians and to enable them to do more, not replace the existing acoustic drums.

Here is a great example. Kevin Haskins from Bauhaus came to Roland in 2019 with a request. Bauhaus was preparing to do a few reunion shows at the Hollywood Palladium in Los Angeles after a long time of silence. This was big pressure. And Kevin told me that he couldn’t play songs from five different records on the same kit, it just wouldn’t work, it wouldn’t sound true to the original recordings. He was worried because he played on those records quite a long time ago, and he had no exact recollection of how they created those different drum sounds and effects. But he knew that he couldn’t use the same kit on every song, and that if he did, sonically it just wouldn’t work. So he looked at the V-Drums kit as a solution. In the end, his drums sounded powerful and amazingly consistent, and exactly how they were on the records, and Kevin was receiving so many great comments from fans and fellow drummers! Advertisement

Later when the TD-50X came out, Kevin spent a lot of time programming and creating his drum sounds again, and like Butch, he wasn’t happy about the time it would take to start from scratch. But then he called me and said, “I can hear the difference, and the hi-hat is a big improvement, too.” Now he is using the TD-50X and the TD-50KVX V-Drums kit live exclusively. The rest is history. So if Kevin Haskins is using the TD-50X and V-Drums with Bauhaus on stage, I think anyone can. Creating the solution to the problem of transitioning from the recording to the live performance was the impetus for these instruments. We are giving drummers an instrument to play, use it as they want, and let the instrument help them to expand their mind and creativity.

MD: Unfortunately, it’s a fundamentalist world that we live in. Everything is black or white, good or bad, Mac or PC, acoustic or electronic. And today that is just not how anything works. Life is lived in the grey area, and that’s what Hybrid Drumming is. That is why Tony Verderosa calls his column “Creative Percussion Controllers,” because that’s what we are now.

IL: I call it the “vs” world. Mac vs. PC, analog vs. digital, it’s just not applicable anymore.

MD: In all aspects of life, it’s a blended world, we all just have to accept that. Why are drums and drummers the last thing on earth that we are refusing to “blend?” Igor who else is using the new TD-50X and the new V-Drums pads? Advertisement

IL: Aside from Butch Vig and Kevin Haskins from Bauhaus, Charlie Benante in Anthrax is using them, along with monster drummers like Brian Frasier Moore and Aaron Draper. Journey is touring with two VAD706 kits. And like I said, many of the leading pop acts like Devon “Stixx” Taylor with Justin Bieber, Josh Dunn with Twenty One Pilots, Zak Starkey with The Who, Will Hunt from Evanescence, and Doja Cat are using them, too. And the list goes on.

JP: And a lot of houses of worship are using them, too, because (like what Butch said) those sound shields are really not the “magic answer” that they seem to be. We are also starting to hear from many small venues in Nashville that are using the V-Drums as well. Some venues are just acoustic nightmares and the V-Drums solve that.

MD: Butch what type of adjustments did you have to make to use the TD-50 and V-Drums live?

BV: When you are starting to use the V-Drums live, you have to take the time to create a really good headphone or in-ear mix. When a drummer plays an acoustic kit, we automatically get a natural acoustic mix of our drums, what they sound like in a room. When you play V-Drums, the sound is not right in your face, there is no natural room sound. You have to be patient enough to create a good monitor mix for yourself, but once you get your own mix dialed in, you’ll love it. Advertisement

MD: What a good point. But let’s take that further, what did you do to really dial in your monitor mix?

BV: I have my loops down the center, and then I created a nice stereo mix of the drums, so everything is panned as it would be on an acoustic set. Then I have the rest of the band panned exactly as they are on stage. If Duke (Garbage guitarist) is stage left, I pan him slightly left. Eric Avery is usually center stage, so his bass is in the center of my headphone mix. We usually rehearse for a tour for about two weeks. That time is spent getting the muscle memory back to tighten up the songs. But a lot of that time is spent dialing in my (and everyone else’s) headphone mix. It’s that important!

MD: Are you wearing headphones on stage, or are you using in ears?

BV: I used to wear in-ears. But now I have the gun muff style headphones that have Sony drivers mounted inside of them, and I have used them on the last few tours. The reason I went to those is because in a lot of the larger venues there is still a lot of low frequencies rolling around, and that was leaking into my in-ear mix. The gun muff phones cut out a lot of that low end rumble and tightens up my mix considerably. It doesn’t look as cool, but I am more concerned with making my monitor mix sound great.

MD: Do you use the GK Ultraphones, those are the gun muff phones that have the Sony drivers mounted in them, made by drummer Gordy Knudsen. I use them and swear by them.

BV: I think those are the ones that I use. I have been playing music for 40 years, and I have always been very cautious about my ears. I always have -15 dB filters in my pocket that I can pop in if I am in an overly loud environment. Therefore, I try to keep my mix on stage relatively quiet. Now with those headphones I can play a two-hour show and have absolutely no ear fatigue. Advertisement

MD: How are your ears in general?

BV: Pretty good, occasionally I get a bit of ear fatigue after long days in a studio. I resist the temptation to crank up a mix in the studio. When the band or the record company wants to crank up a new song because they are excited to hear it, I usually leave the room and get a cup of coffee. If I get really tired, I might have a little ring in my left ear, but it dissipates if I lay off of the coffee, get some rest, don’t drink too much wine, and lay off of the loud music.

MD: Have you used the TD-50X on a lot of records yet?

BV: The new Silversun Pickups record Physical Thrills just came out last week, and we recorded some of the drums here at my house on the TD-50X. We spent time tracking the entire record, and then we brought the tracks here and added drums. Amazingly, once we finished each drum track it was almost like we had a completed master because the drum sound was already treated with compression and ambience within the TD-50X. There are three or four songs on that new record that had the new TD-50X.

BV: There were six songs from the last Garbage record No Gods No Masters that were all TD-50X. I still have a DW kit set up in a room here at home, but to be honest, my home recording studio room is a rectangle room with drywall, and no sound treatment, it’s pretty trashy sounding. It’s the room where I watch Packer’s football games, it is NOT (!!!) a “sonic temple.” When I play an acoustic kit in there, I think ‘this room sounds like shit!’ But when I play my TD-50 kit, I think, ‘wow this room sound amazing.’ Advertisement

IL: I am so happy that Butch agreed to do this interview, without musicians like him, we don’t exist. Artists like him propel us at Roland forward.

MD: And drummers like him push drumming forward.

IL: When he comes back to us and say that an instrument sounds and works great, it makes us better. He has been an amazing inspiration in creating the new Roland TD-50X and especially, the new digital hi-hat.

BV: I gotta say thanks to Roland because they are making my life much easier!

MD: We are going to move on and talk to Butch Vig “the producer.” I‘m not even sure where to start this conversation, because you have produced so many legendary recordings, and great drummers. But let’s start with some conceptual stuff first. In my past I have worked with and interviewed several talented music producers. In this time, I have heard the sentiment that rock and roll is a “producer’s medium” many times. Do you agree with this?

BV: Rock and roll is the combination of an attitude that is mixed with a song that (hopefully) has great lyrics. Those lyrics can be powerful, they can get you excited or motivated, they can challenge you as a listener, or they can push your buttons emotionally in a way you can connect with. It seems simple in theory to record a rock band, mic up the guitar, bass, and drums, with maybe some keyboards, and a hit record. But sonically what can be done in a studio is incredible. The way that sounds and sonic space can be manipulated, and how the listener perceives all of that is extremely powerful. That is why I like to walk into a recording studio every day. The studio is not a mystery, it’s an adventure. Every time I go into the studio to record something, and I think it is going to go in a certain direction, something happens. That means that something goes in a completely unexpected direction, and hopefully that will be for the better. Some of that is the unpredictability that comes from artists. Sometimes they have no idea where they are going to go on any given day, but that unpredictability is the excitement for me. Advertisement

I grew up listening to classic rock in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. My mom was a music teacher, and she loved the Beatles. But she also loved Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Nat “King” Cole, Barbara Streisand, and Frank Sinatra. When I started falling in love with rock and roll, I was listening to The Who, and I couldn’t figure out what was going on, it was this crazy chaos. But the production on those Who records was unbelievable. The first time that I heard “Pinball Wizard” I couldn’t figure out what was going on. Townshend was strumming the acoustic panned hard right, a distorted guitar was panned hard left with tons of reverb. Then Keith Moon and John Entwistle put down this pulsing groove. The production always fascinated me. The Beatles and George Martin (of course) pushed the bar so high that we are all still emulating (to some extent) what they did in the ‘60s.

In college, I cut my teeth listening to glam and new wave bands. I was a huge Roxy Music fan. I loved Chris Thomas, he was the producer who produced the Sex Pistols, XTC, and The Pretenders first album, which is genius. I loved the fact that you could put on 10 records from the late ‘70s or early ‘80s and they would all sound completely different. The production was amazing, there was an endless palette that could be explored and tapped into in the studio. That’s when I decided I wanted to be a producer. Walking into a recording studio is such a thrill for me, and that’s why I keep doing it after all of these years, it’s always an adventure.

MD: What do you consider to be your style of production, or do you even think that you have a style?

BV: I don’t know if I am the best person to answer that. I try to capture the essence of the artist that I am working with. There are some drum sounds and guitar tones that I gravitate towards. The mixing sensibilities that I gravitate towards are probably not all that obvious to me, because it’s just the way that I hear music, and how music makes sense to me. That might be a good thing or a bad thing, who knows… Sometimes I do have to deconstruct my own thinking to force myself to go into a new territory. Advertisement

Being a drummer, I was always obsessed with the sounds of drums. I didn’t have any formal drum training, I never went to a recording school, and I never apprenticed at a studio. I did everything by trial and error. Duke Erikson (from Garbage) and I were in a band called Spooner, and we worked with another local band called Shoes. They were a luscious power pop band. We recorded the first Spooner album with guitarist Gary Klebe (from Shoes) producing, and he sort of mentored me. While we were recording, I asked a ton of questions. I probably annoyed him, but he was patient, and he answered my questions, and that’s how I learned.

Steve Marker and I started Smart Studios in 1984 in a warehouse with an eight-track recorder and some really cheap recording gear. We had a big room that we deadened with a thousand egg carton flats to deaden up the drywall. It didn’t sound particularly good, but the bands that came in didn’t sound that good either. We recorded a bunch of scruffy punk bands that had never been in a studio and didn’t know what they were doing. But we didn’t know what we were doing either. We all learned together.

Because I was raised on pop music, I always want records to sound focused. I tell that to bands all of the time, whether it’s lyrically, arrangements, performance, whatever… I like things to be focused. Early in my career as a producer I got to work with bands like Killdozer and Tar Babies, and those records are what led directly to me working with Nirvana and Smashing Pumpkins. Billy Corgan and Kurt Cobain reached out to me because there was “something” happening on those records that they were interested in. Advertisement

MD: Did you play drums in Spooner?

BV: I played drums, and Duke Eriksen from Garbage played guitar and was the lead vocalist. We did several DIY recordings with Spooner. I think because I was exposed to so much different music early on, that I never felt that any kind of music had to sound a certain way. I remember wondering, “Why can’t a punk record have a string section? Why can’t a Killdozer record have the vocals mixed up really loud and in your face?” Hearing all of the different styles of music early on informed me that you could do anything that you wanted in the studio as long as it made sense for the artist that you were working with. My job is to help the artist find and achieve their vision.

MD: How much time do you spend trying to find the perfect room for a band to record in?

BV: I don’t know if I try to find the “perfect” room. But I do think it’s really important to find the room that will have the vibe that the record needs to have. A studio creates the psycho-acoustic space that a listener perceives in a track. That space is where the listener is going to place that band and that song. I have been lucky enough to record in some fantastic rooms. I live in L.A., and there are some great rooms to record drums here. East West Studio 2 is a great sounding room, it’s kind of bullet proof. I can put room mics anywhere in that room and my job is done.

I call recording studios “sonic temples.” I tell young bands and engineers that they need to go into as many of those sonic temples as they can and record. There is a reason that so many great records have been made at Capitol, United, Ocean Way, or The Power Station. Part of what makes your favorite albums sound so killer is the sound and the vibe of those rooms. Those rooms created and captured magic. Advertisement

Sure, everyone has computers now, and they have tons of drum samples and loops. You can make incredible music in your bedroom, your song can go viral, and millions of people can hear it in 24 hours. But I feel more young musicians and engineers have to go into one of these kick ass “sonic temples” and create some music. They can actually learn from the room. The first time that I ever walked into The Power Station, I hit a snare drum and thought, “Holy shit, this is the best snare drum sound that I have ever heard.”

I had never been in Sound City before I worked there. But when I walked in for the first time, I heard that room and I saw that vintage Neve console, I knew it was something special. I knew the records that had been done there: Tom Petty, Fleetwood Mac, and scores of others. But Sound City didn’t have a fancy lounge, a bunch of cool outboard gear, or even a great collection of mics. It was just a great sounding room!

MD: I know you are a gear head and a great producer, so what are some of your favorite drum sounds and go-to drums? What are the drum sounds that you hear in your head?

BV: When I heard Keith Moon, I stopped playing piano, and started playing drums. I realized very quickly that I wasn’t Keith Moon (laughs), but I could get close to the style of Ringo and Charlie Watts drumming. Therefore, I would put on Beatles and Stones records and play along. That’s how I learned to play drums. As the Beatles developed, and George Martin and Geoff Emerick started paying more attention to the drum sounds through using different mics, compression, and eq, I started to pay attention to how Ringo’s drums sounded. That is where it started for me, I became obsessed with drum sounds. When I really felt like I was getting an idea of how different rooms sounded was in the ‘80s. The ‘70s had some great drum sounds that were very clean in the mix, but the overall sound was pretty dead. There were some fantastic records made in the ‘70s, and I happen to believe that 1971 was the single greatest year for music ever, but that is a whole different discussion. Advertisement

All of those classic rock bands were gods, we all put them on pedestals. But I felt a kinship to the new punk and new wave bands, I was a part of that. That led me to get really obsessed with Steve Lillywhite’s gated drum sounds, because he was the first one to really crank up the room mics. His drum sounds were so “vibey.” The first thing that I learned was you had to put drums into a big space to get a big sound. You had to manipulate the drums in a big space to get that sound.

MD: What were some of your favorite Lillywhite drum recordings?

BV: I love the work that he did with U2. I saw U2 at a club in Madison called Merlin’s, everybody played there. But when I saw them, Steve Lillywhite was there recording the show, he was recording the whole tour. Steve Marker (from Garbage) was a bouncer at Merlin’s, so he let me in for their soundcheck, and I just started talking to Steve Lillywhite. He taught me about gates and how you can set the release times for the tempo of the song and trigger them from bass and snare drums. The next day I went out and bought a cheap Dynamite Compressor-Noise Gate, and we started using it at Smart Studios. We had already bought a used plate reverb from a studio in Chicago and one of the first digital reverbs; so we ran those sounds through the Dynamite Noise Gate. Drummers loved it and started to ask me what I was doing, my reply was, “I’m ripping off Steve Lillywhite!”

When I did the Killdozer record Twelve Point Buck, the band let me go crazy with drum sounds. I used those reverbs and that gate a lot. I got some great ambience on those drum sounds. But those sounds were perfect for the band and their music because a lot of their tunes were really slow and there was a lot of space between the notes. Advertisement

MD: I know some producers are more arrangers, some are more psychologists, some are more engineers, and some are organizers. What type of producer are you?

BV: When I started out, I was all of that. I was making production decisions, I was getting snare drum sounds, I was making sure the vibe between the band members was cool, I was making the coffee, I was doing everything. As I have developed as a producer, I like to have an engineer now so I can focus on the song and the vibe, and I have worked with a bunch of great engineers. But I mostly work with Billy Bush, our engineer with Garbage, because we don’t even have to speak, he knows intuitively what I am thinking. He fixes problems before I even know they exist. His presence allows me more time to listen to the sounds and the performance and be more of a psychologist with the band. However, I still get in there and tweak drum sounds. I usually have drummers tune their snares down, you won’t find many high-pitched snare sounds on my recordings. I like thick snare sounds. But it all depends on the song. If a song is faster, sometimes the snare does have to have a higher pitch, so the transients and the sustain of the snare tone don’t create a lag in the tempo of the song. Everything really is dictated by the song.

MD: Every engineer, and many producers, have specific snare drums that they love. What are your go-to snare drums, and what are some of your favorite snare drum sounds?

BV: My favorite snare and bass drum sound is “When the Levee Breaks.” I guess Andy Johns did that with three or four mics, and he created that little slap-back delay, man that is just so good. But so much of that sound is John Bonham playing drums, the dynamics of the drummer are so much of the drum sound, people tend to forget that. Throughout the years, drummers have come into a project and asked me to get their drums to sound like John Bonham or Dave Grohl, and my response is always, “Well, you’re not John Bonham or Dave Grohl.” But on the other hand, it’s cool when drummers say that because it gives me a reference point from which to start. In those cases, I listen to how that particular drummer plays, and what the song sounds like. Then we can make adjustments to create a great drum track that everyone is happy with and that sounds like that particular band or drummer.

MD: How about specific snares?

BV: I have an older “nothing fancy” Yamaha steel 6.5×14 snare that came with my Yamaha Recording drums back in the ‘80s. Jimmy Chamberlain used that on part of Gish, and we call it the Gish snare. There are some specific overtones in that drum that sound wonderful. He also used a fantastic Gretsch snare on Gish. I take that Yamaha drum to all of my sessions, it has 42 strand snare wires, and even if I deaden it down, it has a great transient pop to it. Advertisement

I have a Dunnett Titanium snare that Tre Cool gave to me that sounds fantastic. I have a wood Gretsch drum that I like, I have a few DW snares that I use a lot. Of course, I have a 6.5 Ludwig Supraphonic that I like a lot. I have a ‘70s Black Beauty, but I have found that the Black Beauty can be temperamental. When I go into a session, I like to have six to ten snare drums that I can choose from. My drum tech Mike Fasano has a drum that we call “Big Red” that was used on Guns and Roses “November Rain,” and it just sounds huge. That’s a great drum. Mike also has a Gretsch kit that I use the kick and toms.

MD: Wolfgang Van Halen mentioned that kit to me because he used it on the Mammoth record.

BV: Mike usually brings ten snare drums to a session for me, and then I’ll bring four and that will provide me with enough choices. He knows what snares I like. Sometimes he’ll provide me with a choice of toms too. He has some that are more dialed back, and some that are more lively. He does the same with cymbals. Sometimes you want cymbals that will cut, and sometimes you need cymbals that will blend and sound a bit softer. I’ll often tell Billy to use ribbons instead of condenser microphones as overheads because I want a softer cymbal sound. But it all depends on the track. Your microphone choice will always dictate how the drum kit sounds.

MD: How about favorite mics?

BV: My favorite kick drum mics are D12s, Fet 47s, and RE20s. Back in the Smart Sound days my go to snare drum mics were (of course) Shure 57s. I like to use AKG 451s as long as the drummer isn’t pounding the hi-hats too much. If he is, I’ll pop up a Beyer 160 Ribbon that is very forgiving with the hi-hat. Billy and I like to use a Telefunken MD 80 because it’s a little more hyper-cardioid with a tighter pattern and is more “hi-fi” sounding than a 57. That has become my default snare drum mic. I used to always default to Sennheiser 421s on toms, but Steve Albini gave me a tip on Josephson E 22s Condensers, and I really like them. Advertisement

MD: Without giving away any of your secrets, what other things do you rely on in the studio to get great drum sounds?

BV: I like to make bass drum tunnels. That is when I’ll take another bass drum shell and put packing blankets over it so I can mic the bass drum close, and I can also put another mic (usually a Fet 47) out away from the drum as the low end develops for more thump. But the tunnel will prevent a lot of cymbal bleed, especially if you are in a really loud room. We used that on Dave Grohl’s bass drum on Nevermind. It’s a great trick if you want to bring the kick drum up and not have the cymbals come up, too.

Years ago, I was recording young drummers that didn’t have a whole lot of dynamics on the hi-hat so I built a “hi-hat baffler.” Believe it or not, I would take two pizza boxes, and put one under the bottom hi-hat cymbal, and one above the top hi-hat cymbal. I would Velcro the edges together, so they didn’t touch the cymbals, then I’d make a cutout for the drummer to play in. It was really weird and super ugly, and all the drummers freaked out and didn’t like it, but it cut about 80% of the hi-hat bleed out. I used that for two years at Smart Sound, and amazingly one of the bands stole it.

MD: I know everyone always asks you about Nevermind, but you made another all-time classic record more recently that I want to ask you about. I have watched the documentary about making the Foo Fighters Wasting Light, but what else can you tell me about making that record? Because when I first heard it, I knew it was an all-time classic. Advertisement

BV: We had a lot of fun making that record! Dave first approached me and said he wanted to make a record in his garage studio, and I thought that was a cool idea. Then he told me that he wanted to make it on tape, and my heart sank a little bit, as I had moved into the digital world using Pro Tools. But I have made thousands of records on tape so that was fine, but what tape means is this. It’s all about performance! You can’t fix things on tape like you can in Pro Tools, but the band was totally up for it. They knew that they would have to do takes and takes and takes until we got it right, and that’s what we did.

To me, Wasting Light is the record that sounds the most like the Foo Fighters. That record really sounds like what the Foo’s are live in terms of tones, vibe and feel. It’s a little rougher sounding than some of their other records, but I love it!

It breaks my heart that Taylor is gone. Besides being an incredible drummer and just going for it 100% on every single take, he was so much fun to work with, and such a sweet guy. Taylor and Dave were joined at the hip. In some ways Taylor was the heart and soul of the Foos. Taylor was really excited when he heard how we were going to do Wasting Light to tape because he hated when we would Pro Tool his drum parts. He took real pride in the fact that he didn’t have to be edited. He would play a part and although it might not have been perfect, he didn’t want it to be edited. He would rather do the entire take again, he always wanted to nail it! Advertisement

At least once a year Taylor would text me and tell me that he was listening to Gish and ask me all of these geeky drum sound and drum questions about it. He loved that record. I really miss him and I can’t even believe he’s gone.

MD: I gotta admit, I was obsessed with Wasting Light for about four years, and then I just had to stop. Then when Taylor died, I went back to it again. It might sound like sacrilege, but I think that is this generation’s Led Zeppelin IV.

BV: I’m sure he’d be happy to hear you say that.

MD: Talk to me about recording Smashing Pumpkins and Jimmy Chamberlin and Gish.

BV: I was blown away by how the band looked the first time I met them. They looked like freaks, and I loved that. Billy and I clicked right away. We have a great relationship, we really pushed and complimented each other in a lot of ways. Then I heard Jimmy play, and I was floored, he is a monster. We cut Gish at Smart Studios when Studio A was in its first incarnation. The room was pretty live with irregularly shaped drywall with some pretty loud and intense diffusion going on. When we cut the songs for Gish, Jimmy and Billy tracked together with Billy playing rhythm guitar and Jimmy playing drums. They had a very specific thing when they played. It was very push and pull. The front of the bar pushed, and the back of the bar pulled back a little. Advertisement

Jimmy has a great sense of dynamics, and he’s not a super hard hitter. I didn’t have to baffle the hi-hat, and he really played dynamically and very consistently. He made my job easy. I think I used my standard mic setup with a D12 on the kick, a 57 or a 451 on the snare, 421s on toms, and AKG 414s as overheads. Then after Jimmy and Billy tracked, we went back and overdubbed everything. That record took a lot of people by surprise because the Pumpkins got lumped into the alternative rock scene, and Gish was sort of prog-rocky. There were down tempo tunes, lush slow songs, and some were like crazy metal. There are some great grooves on that record. The pattern on “I Am One” was the first thing we tracked, and that is a signature type of groove. That was an incredible record to make. Gish came out about six months before Nirvana’s Nevermind did. I started to get a lot of calls from artists and labels because they heard Gish.

MD: You also did the Pumpkins Siamese Dream too, how did things evolve from Gish to Siamese Dream?

BV: We did Siamese Dream in Atlanta at Triclops. They had a big tracking room and a vintage Neve board. We went there to try and get the band away from any bad influences. Therefore, we didn’t want to go to NY, Chicago, or L.A. We thought Atlanta would be a safe haven, but it wasn’t, Jimmy Chamberlin was getting into trouble from day one. We really pushed the envelope sonically on that record, and we worked really hard. We tracked for five months, and for the last three months we tracked seven days a week. We did that record before Pro Tools, so I did a good deal of tape editing on it.

MD: I was just going to ask you if you were good at chopping tape?

BV: Yes! I was an excellent tape chopper. I could really slice and dice to get the best performances. On the rehearsals for the song “Mayonnaise,” I tapped out the BPM, but when we recorded it, Billy wanted to play it 4 BPMs slower, so it would sound a little dreamier. But every time they played it, it would be faster by the end of the first verse. I set up a click on a Roland drum machine, but every bar got a little faster, and then Jimmy would pull it back, and it wouldn’t sound very good. So I went through and chopped out all the sections where Jimmy would slow it down. There were about 200 micro snare edits on the track, but Billy liked the way it felt. However, because there were so many edits, I had to transfer the drum tracks to another tape for safety concerns, and when we mixed it, I had to sync up the tape with the drum track and a slave reel with the rest of the track. It was a pretty lengthy process, but when you listen the song, it had a fantastic groove. Advertisement

MD: What was it like working on Green Day’s 21st Century Breakdown?

BV: Tre Cool has the fastest hi-hat hand that I have ever worked with! He can play those fast eighth notes consistently, and tight as hell at 200 BPM. I can’t maintain that tempo for very long. And his feel on those tempos is killer. But so much of their groove is driven by Billie Joe’s rhythm guitar playing. Tre is a real drum nerd. They have a complex up in Oakland, and he keeps 60 or 70 sets, and tons of snares, and thousands of cymbals there. But he knows every piece of gear that he has. That meant that we had a lot of sound options when we went in to record. We did a lot of pre-production at their complex, and then at a studio in Newport Beach. So by the time we were tracking at Ocean Way, it went really fast. We tracked for about seven weeks, it was a really old-school way of doing things. I think that album is epic sounding, Billie Joe is such a great songwriter.

MD: You have mentioned tempo a few times, how involved to you get in establishing the “perfect” tempo for a tune?

BV: When I go into pre-production with a band, I don’t use a click. I mark the tempo of the different sections of the tunes, and then more often than not, I will use a tempo map. I did this with the Foos on Wasting Light. I don’t care if different sections of a tune are at slightly different tempos, as long as it feels good. And personally, I think drum fills sound best when they rush a little bit. I like to make the grid fit the band. That drives my engineer Billy crazy because he has to deal with that when he is editing.

What I did with the Foos and Taylor is I would have the click coming from a drum machine, and I’ll program the different tempos in the machine next to each other, and when the tempo change happens for a chorus or a verse, I change the tempo on the drum machine by manually changing the pattern. That puts some pressure on me because I have to make the change at the right time, a split second before the downbeat of the next section, and Taylor never knew I was doing it. But, again, in the end the songs felt great and that’s what counts. Advertisement

There is a tempo where a song flows effortlessly. Sometimes one BPM either way can make a big difference. It affects the way the drummer, the rhythm guitarist, or the vocalist will play their parts. Sometimes a song might work at one tempo instrumentally, but when the vocals are added, it doesn’t work. A tempo has to work with the whole band. So to answer your question, YES I do get pretty obsessive with tempos!

When I did Let Your Dim Light Shine with Soul Asylum, Sterling Campbell played drums, he is a super powerful drummer. On the last day that we were in the studio we listened back to a track that we had done weeks before called “Misery.” I asked the band to go back in and recut the tune. They were shocked, they thought they were done recording, but that tune just didn’t feel right to me. They re-did it, and it wound up being the lead track on the record. I cracked the whip at the eleventh-hour and it worked.

MD: On the Foo Fighters Sonic Highways, in which every tune was done at a different studio, how did you manage to create a sonic continuity from track to track?

BV: That has to do with James Brown who was the engineer and how he made the room ambience match from track to track. That record was an adventure, because (as you said) the environments were all different, some of them weren’t even studios. Advertisement

The first track that we cut for Sonic Highways was done at Steve Albini’s Electrical Audio in Chicago. Steve built an incredible drum room using imported bricks from New Mexico (or someplace?) Like the Power Station, it is an idiot-proof drum room. When we were tracking “Something from Nothing” there were some really tricky parts and some hard transitions. It’s a complicated song. It starts with Dave playing a guitar thing, then it goes into a swing thing, the second part is a funk thing, and then at the end it explodes into this big floor tom groove. I was prepared to cut the song in sections so I could cut up the tape and create a take. But that was a call to arms for Taylor. He did not want me to have to edit his drum part together! They went for the first take, and Taylor completely nailed it. I was on the edge of my seat for the whole take, the hair was standing up on the back of my neck, and they got through it, and I said, “Taylor I think you nailed it.” They came into the booth to listen to it, and Taylor had this big shit eating grin on his face. It is the first track on the record, and he was so proud of the fact that he nailed that really hard song in one take, and I am so happy to tell that story.

MD: What can you tell me about your band 5 Billion In Diamonds.

BV: We have two albums out. That band’s music is really informed by ‘60s and ‘70s film soundtracks. The two DJ’s in the band James Grillo and Andy Spaceland love that time period of music. All three of us are huge fans of film music. I probably listen to film music scores as much as I listen to pop and rock music. There is so much wonderful “non-traditional” soundtrack music being created these days. In the beginning, film soundtracks were orchestral, then that began to change in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Today you can create a soundtrack with Sound Design. It’s like pop music is today, it’s a hybrid, you can take elements from anywhere and as long as it creates a mood or an emotion it’s going to work.

MD: What is some of your favorite soundtrack music?

BV: I’m a huge fan of John Barry, I love Giorgio Moroder, I love the music of John Carpenter films, he actually did a lot of his own scoring. He’s really minimalist. He did the score for The Thing, and I love it. One of my favorite scores is Quincy Jones’ score for In Cold Blood. Advertisement

MD: You have another band called The Emperors of Wyoming, what’s that about?

BV: That is a project that came through file sharing with some of my old friends. We were sending files between all of the guys because we are all in different places.

MD: How do you sequence (arrange the order of the tunes) on a record? I think that is a bit of a lost art.

BV: That’s a very important thing to me as well. I still listen to records all of the way through, and I still believe that is how records should be listened to because that is how artists make them. I realize that people like you and I are anomalies, because many people don’t even listen to entire tracks anymore. When I make a record, I want it to be a listening experience. I still like the vinyl experience, but I wish more people would listen to the music as it was intended to be heard.

MD: You have an interesting “position” in Garbage because here you are this influential producer, and you are also a member of a successful band.

BV: When I am producing the Foos or the Pumpkins it is their music, and it’s my job to help them find their vision and motivate them to get great performances. I approach Garbage completely differently. When I am in Garbage, I can be a drummer, I can be songwriter, I can play guitar or keyboards, I can engineer, I can order lunch or open a bottle of wine. However, everyone in the band can do any of those things. We swap the roles in the band on any given day, it keeps things really fresh.

When we write a tune, it usually starts with a beat. Whether that beat comes from me playing a live kit, or me programming a loop, or bringing in a sample that we’ll play over. The exciting thing about Garbage is there are no rules, and every song starts from a different place. Since we came back from our hiatus in 2012, I feel like our songs are more lyric driven. We are trying to taper the song to match the vibe of Shirley’s vocals. On No Gods No Masters although there are different drum sounds and different textures on every song, the thread of continuity that we were talking about before, comes from Shirley’s vocals. Advertisement

MD: How does your producer hat influence your band member hat?

BV: Sometimes the band does look to me to have an opinion or guide a song, especially if we have hit a creative wall. I probably step in more when we disagree on a part or a vibe.

MD: Which brings me to this question. As a producer, as a bandmember, and as a drummer, how do you know when something is done?

BV: When the budget runs out! Ha! No, that is a great question. As a producer I am very conscious of staying within a bands budget and timeframe. With Garbage I am guilty of a lot of tweaking. I am a tweaker. I like to go in and sonically manipulate things. Whether it’s with plug-ins, or routing stuff out to stomp box pedals. Duke, Steve, and I like to do what we call “lab rat days.” That’s when we just go in and mess around in the studio all day. More often than not, Shirley is the one in Garbage that says when the song is finished. Duke, Steve, and I have a tendency to keep adding more and more, but sometimes we have to tell ourselves to strip things back a bit and let the track breathe.

MD: When you aren’t using your TD-50X, and you are recording real acoustic drums, what drums do you use?

BV: I have a DW kit here, I have my “Gish” and the Dunnett snares here as well. I usually add the real drums last on Garbage tunes. We’ll often record to a loop, and get everyone else’s parts done, and then I’ll go in and put the live drums down at the end. I did that on the new Silversun Pickups album Physical Thrills too. By doing it that way, I can tell how the drums are supposed to sound. I think when you have a track that is pretty fully formed, it is easier to get the drum sound. I think the same is true of bass sounds too. When the track is fully formed you can tell how much top end or grit you want from the bass. I know that sounds completely backwards, but that is what I have been doing lately.

MD: Do you have any cymbal preferences?

BV: The hi-hat is the most important cymbal to me. That (and the ride) is where I keep time. I’m not too fussy with crashes. Sometimes I like crashes to cut through, but usually I like them to sit back in the mix and not stick out too much. Especially in Garbage, there is already so much information going on sonically that I don’t need cymbals to take up that much space. I do like using ribbon mics on crashes because I feel like they have a softer top end, and you can put them louder in the mix without them ripping your head off. Advertisement

Mike Fasano found a great pair of hi-hats for me a while back. They are Ludwig cymbals. One is from the ‘50s, and one is from the ‘60s, and they sound great because there is no high end overtones in them. They are so old and dull that that there are no overtones left, and they sit perfectly in a mix.

MD: What drummer haven’t you worked with that you would like to work with in the future?

BV: I’m so lucky to have worked with so many great drummers: Dave Grohl, Jimmy Chamberlin, Taylor Hawkins, Steve Shelley from Sonic Youth, Dom from Muse is phenomenal, Adam from AFI, Tre Cool, Sterling Campbell is total bad-ass, Keltner is the bomb, Omar Hakim is fantastic and has such a great vibe behind the kit.

I’ll tell you this, when you work with a great drummer, it makes a producer’s job much easier. I’m the luckiest guy in the world to have worked with all of those great drummers.

MD: No, we are the luckiest people in the world to hear you talk about the art of making and recording music. Thanks!!!!