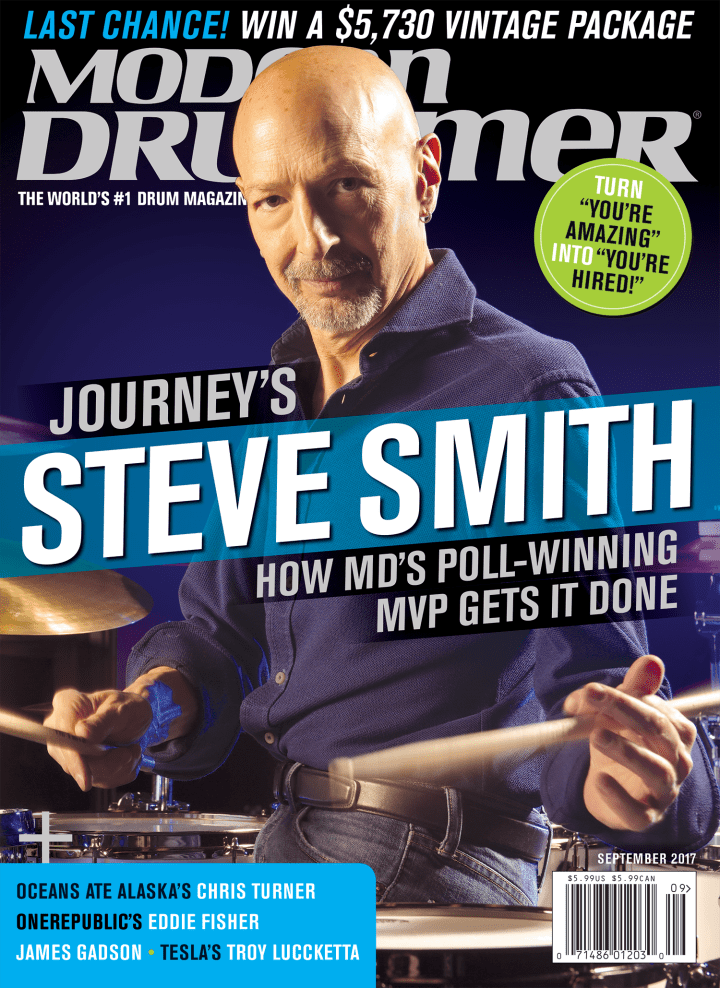

Steve Smith

Last year he rejoined the band with which he wrote and recorded some of the most famous drum parts in history. And like every other musical situation he confronts, Journey’s drummer approached this one not as an excuse to relax into a familiar role but as a golden opportunity to further his artistic growth. This, in a nutshell, is why we still pay such close attention every time the man sits behind a drumset.

Long-overdue induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame might be a big deal to most drummers, but Steve Smith is more excited to win not one but three categories in the 2017 Modern Drummer Readers Poll: MVP, Rock, and Educational Product. “I’m a longtime Modern Drummer reader, from the very first issue in 1977 with Buddy Rich on the cover, which coincides with when I began with Sonor drums—forty years,” Smith says. “And I put a lot of meaning into Modern Drummer’s perspectives and the readers’ perspectives. I’ve always been very excited to be in the Readers Poll, so this year has been way over the top. It’s acknowledgement from my peers in many ways, my fellow drummers. That means a lot to me.”

Well-deserved honors, of course—and then there’s that whole Journey thing. After replacing drummer Aynsley Dunbar in the late 1970s, it was Smith who appeared on the band’s classic albums and golden-era tours through the mid-’80s, and who was part of the lineup that fans remember with the greatest fondness. Those fans were treated to remarkable news in 2016 when it was announced that Smith would rejoin the group for his first live Journey dates in over thirty years. And he’s still going. Advertisement

So now if you get the chance to see Journey on a stage, you’ll hear classic anthems like “Don’t Stop Believin,’” “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart),” and “Open Arms” performed by the man who wrote the original drum parts to those songs, but with a little something different this time around, as Smith elaborates on below. And if relearning intricate patterns from a lifetime ago wasn’t enough, Smith still found time recently to release a new Steps Ahead disc, Steppin’ Out; record and perform with his own jazz fusion group, Vital Information; occasionally fill in for Simon Phillips with the brilliant keyboardist Hiromi; and find new ways to practice and apply Konnakol, the South Indian vocal percussion vocabulary.

And it hardly ends there. Recently Smith released The Fabric of Rhythm, a deluxe package containing a vinyl solo album of drum pieces related to his own lighted-sticks canvas art, photos of those art pieces, his written descriptions of the music and art, and cool historical pictures. And during his downtime, Smith studied different examples of matched grip, which culminated with the informative DVD/book release Pathways of Motion.

Modern Drummer caught up with Smith in a recording studio just a couple days after the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony. The drummer was there with Vital Information guitarist Vinny Valentino, tracking drum parts for Drum Fantasy Camp, a yearly instructional and performance event that in the past has featured world-class players like Dave Weckl, Chris Coleman, and Todd Sucherman. Steve was relaxed and confident when asked to blow over the drum solo section of the Steely Dan classic “Aja.” Though he hadn’t heard the brilliant Steve Gadd–ified album cut in a while, he refrained from listening to it for reference and proceeded with take after take of beautiful phrasing, perfect control, chops galore, and his trademark musicality. Advertisement

When we sat down, we began with (finally!) that little award he’d just received.

MD: How does it feel to be a Rock Hall inductee?

Steve: There’s no intrinsic meaning to anything other than what you give it. And with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, it’s a self-appointed body of people that got together and decided to be tastemakers and induct people or leave people out. So as a musician oriented to playing jazz and rock, I didn’t think about it very much. It wasn’t important to me whether I was in or not.

And I think that’s the same with any person working in any kind of field, whether you’re a writer and some people win a Pulitzer Prize or you’re some kind of activist and you win a Noble Peace Prize: It’s not going to change your work or work ethic. With the hall, it’s a wonderful accolade, but what got me thinking about it was that the Journey fans were so excited and it means a lot to them. There was a long voting process, and in a nice way Journey won the popular vote. Then we knew we were going to get in and there was this stressful buildup. What are you going to wear? And then you have to write a speech. And what are we going to play?

But once I got there, I hung out backstage with Bill Bruford and we had a nice long talk. Once the show started, it was interesting to see the Electric Light Orchestra and Joan Baez, and it was a really wonderful event. I was able to get on stage and in two and a half minutes speak about my story and acknowledge some of my influences and how the path led to me playing rock. One of the things I walked away with was that I could see how helpful it is to bring new fans in. I never really listened to Joan Baez or Tupac Shakur, but after seeing their presentations, I want to check them out. So maybe it’ll help Journey’s popularity even more. I’m happy to be inducted, and I just hope it doesn’t ruin my jazz career. [laughs] Advertisement

The Long Journey Home

MD: What’s it like to revisit the Journey material after so long?

Steve: When I started playing with Journey again in 2016, it had been thirty-two years since I played live with the band. We did the album Trial by Fire [in 1996], but that was a studio project and we didn’t revisit any of the old songs. We didn’t do “Don’t Stop Believin’” or “Who’s Crying Now,” so I didn’t remember any of those songs, because I hadn’t listened to them in a long time. [laughs] And that was okay, because I approached the gig like any other gig that I get called for. I transcribed a big list of songs that the band wanted me to learn, note-for-note what I played on the albums.

MD: Were you surprised while transcribing?

Steve: I was. It was looser than I remembered it being. Looser, as in the parts were not completely etched in stone. I noticed that I had a verse groove but I wasn’t super-strict with it. And then the chorus, it was a groove, but it wasn’t an exact part, for most of the music. As long as it felt right, it was pretty loose. Then there were certain fills that are part of the song. In “Separate Ways” I play the exact same fills every night. “Faithfully,” the same fills from the record, every night, because they’ve become part of the song.

So I made decisions about where to be loose with the fills and where to play verbatim what was on the record. Then I started to update the grooves a little bit, update the orchestration. Some of that came from seeing Andrés Forero with Hamilton, watching him in the pit with five snare drums and all the orchestrational ideas you can come up with. Sometimes you play with no hi-hat and sometimes with the hi-hat. And I started copping some of those R&B grooves from Hamilton and sticking them in the Journey music to make it a little funkier. It became a creative project for me. Advertisement

Then I decided to go back to a double bass drumset, add a third floor tom, and have three snares for fills. You’re hearing a snare fill, but the pitch goes up and down. And now I’m using three snares on the newest Vital Information record. The process became a lot of fun, relearning the songs, and in some ways I left well enough alone.

MD: Sounds like you really applied yourself.

Steve: The process of memorizing all that music did take a while. It was like starting over. Then I had to condition myself to play that big rock sound for a ninety-minute show. There’s a lot of dynamic shifts on the gigs with my own band, where I’ll play brushes and then play some tunes that are real big. But Journey music is essentially a big sound most of the night, with some dynamics.

To get ready I did a lot of yoga, a lot of practicing and blowing through the songs and improvising, just to get my chops up and have some fun. When I’m on the gig, though, I’m real disciplined and I play very clearly for the music. There’s a feeling now that’s different from when I did Journey in the ’70s and ’80s, when I felt like I was trying to prove myself, and maybe filling this up and that up a little too much. Now I don’t need to do that at all. The guys in the band are really happy with that, because I’m not overdoing it and I’m playing just what they need to hear. And what they tell me is that all the parts are falling into place again. Advertisement

MD: And the band is encouraging of these little tweaks you’re making?

Steve: Oh, yes.

MD: They notice?

Steve: No, I don’t think so. [laughs]

MD: So they’re not tied to the album versions either, because you’re also different from Omar Hakim and Deen Castronovo. [Castronovo played drums with Journey between 1998 and 2015; Hakim did the band’s 2015 summer tour.]

Steve: Omar and Deen are fantastic drummers, but they didn’t come up with those parts to begin with. They learned the parts, but there were specific things that I was thinking about when I played particular parts for something Ross [Valory, bass] or Neal [Schon, guitar] or Jonathan [Cain, keyboards] did. In addition, I was trained by Steve Perry to play in a certain way that gave him support and freedom and brought a certain R&B element to the rock. And of course no one else has been trained by him other than me. [laughs] But also, I went back to the well, the records—though not the live versions, because back in those days we played things too fast live.

MD: And you don’t look like you’re breaking a sweat. Letting the mics do the work?

Steve: During one of the lessons I got from Freddie Gruber, I was sitting in his drum room and I hit the drum really hard, and he said, “Why are you playing it like that? What, are you angry at that drum?” [laughs] And I told him I was trying to get some power here. And he said to me, “Power is for dictators. What you want is a big sound.” And that stayed with me. It’s about being able to draw the tone out of the drum or cymbal and then adjusting the touch. One of the first things he worked on with me was not hitting the drum, but rather just allowing the stick to drop and getting used to that sensation. So you can play without any stroke at all. If you start with letting the stick drop, that gives you a very quiet basis for your dynamic range that then can go up from there. Advertisement

So I’ve learned to play quieter and get a good sound on all of the instruments, and then make the correct balance internally. Like, make the bass drum and snare drum balance to themselves, acoustically, before even thinking about what the mic is going to do. That comes from years of playing on stage in acoustic environments where I’m two feet away from a saxophone player or an acoustic bass player and five feet away from an acoustic piano player. So I really have to control my volume. In a lot of those cases, there’s either no miking on the drums or just an overhead and a bass drum mic. So I’ve trained myself. I don’t play any differently from that on the Journey gig. I play the same way, so I don’t hurt myself. And I don’t play any differently in a studio from the way I do on stage. But that’s taken years of study, practicing, and considering all this stuff.

MD: I saw live footage of Journey from this year where you weren’t using a drum riser. By choice?

Steve: I’m just used to not being on a riser, from all the jazz gigs. And it sounds better to the other musicians. They can walk right up to the drums. There’s a vibe that happens when we’re all on the floor. They can feel the vibration. With a riser, they feel less connected to the drums. But we need the riser to slide the drums off the stage when there’s an opening band.

Staying Vital

MD: The new Vital Information record, Heart of the City, is a mix of standards and originals. You’ve been playing some of these standards for many years. How do you keep it fresh with the arrangements? Advertisement

Steve: There are two ways we do the standards. Some are very thought-out arrangements, and then there are tunes where we play the beginning kind of funk and then go to a swing, and then we do some duets. It’s a lot looser. It’s not hard to keep standards fresh, because every time I play with whoever I play them with, those personalities make it new. So it’s a lot of fun for us, and we don’t have a lot of time to get together to rehearse and write original music, so we can fill up the set with standards that really work. People want to see us play our instruments and improvise and create a vibe and energy, and it can be done with all those elements.

MD: You’ve been doing the South Indian percussive vocalizing called Konnakol for a while now too. What’s your relationship with the art?

Steve: I started that in 2002. I’ve learned enough to be fluent with it, to the degree that I am fluent with it. [laughs] First, I had some lessons with a South Indian teacher, and shortly after that I started to play Indian fusion music with the group Summit, with Zakir Hussain and George Brooks. That was on-the-job training, so it wasn’t just studying and being at home practicing. Within one year of investigating Konnakol rhythms, I was working a lot more with Indian musicians, because when they heard there was a Western drummer that could understand their music, I was getting hired a lot. And the more I got hired, the more I had to learn different compositions quickly and perform them.

Then I started to mess around at home with Konnakol and drumming at the same time. Traditionally, Konnakol is unaccompanied. So that was a big decision, in a way. Could I play the drums and do Konnakol at the same time? It took a while to get that coordination, but then I started to bring that into the Vital Information music. Advertisement

MD: Like “Open Dialogue” on the new record, where you lay the Konnakol and drums over a little funk groove?

Steve: Yes. I’ve been doing that kind of thing with a lot of the groups I’ve been touring with. I’ll do it with Mike Stern, and Randy Brecker, and a little bit with Steps Ahead. For “Open Dialogue,” I also doubled the vocal in the studio.

There are two ways I do Konnakol and drumming. One is that I play a groove and do the Konnakol over it. The other is that I do the Konnakol and exactly double it with the drums. So that was an exercise in how to be able to do that, to first learn and memorize the composition and then voice it on the drumset. That was a long time in the making, and I’m pretty comfortable with it now. It feels very natural.

MD: And Zakir is not a bad on-the-job trainer.

Steve: He’s unbelievable. It’s inspiring and humbling to play with Zakir. As much as I consider myself a good Western drumset player, when I play with him, he can go so far with his rhythmic understanding, repertoire, and abilities…it’s really incredible to be in the presence of that. So no matter how far I go, he can always go further. And he loves to challenge me. It’s been a big part of my musical growth over the last fifteen years. Advertisement

MD: “Eight + Five” also has some interesting stuff going on with the Konnakol.

Steve: That was a tune in thirteen that we wrote together. I came up with the entire tune as a rhythmic structure. It was exploring a lot of different ways to play in thirteen, combining eight and five. [Bassist] Baron Browne brought the final pieces to the puzzle in the studio, with a melody and some harmony. I’m happy with that one. I notice the Vital Information fans like it when we do the odd-time tunes. On the album before, we did one in fifteen, and it’s our most-requested tune.

Multimedia Man

MD: What was the idea behind your book and audio package The Fabric of Rhythm?

Steve: The people from SceneFour came up with the idea of doing a book. They had made two books with Carl Palmer and one with Dave Lombardo already. So I thought it was a great idea for a book to feature all thirteen pieces of art [photographs where Smith uses lighted sticks]. But I had the idea of making a solo record to go with it. I’ve had a lot of solos on records and have come up with many ideas for solo pieces for clinics and live gigs, but the idea to record a piece of music for a piece of art made a lot of sense to me. And they wanted to make a vinyl LP out of it.

I took it seriously, like I was going in to make a record. So I booked studio time and organized all my ideas. It was really fun and very creative, and I could draw the connection between the art and the drumming in every piece. Then I went through the process of writing about each piece of art, how it came about and what my thoughts were, and then I wrote about the solo drumming. That was interesting to get into the rhythms and the technical concepts that I’m using. I thought if people are going to check out this book, they’re going to want these details. The way it’s intended to be used is you put on the record, you look at the art, you read about the art, and then you read about the solo and then listen to the solo. Advertisement

MD: “Condor” and “Interdependence” are really creative.

Steve: “Condor” is a slower piece composed for three snare drums to play in unison. Then I just improvised to see what I can do with some metric modulation.

I’ve recorded the idea for “Interdependence” before, playing the left-hand ostinato on my side snare and then playing the melodies with my right hand. I did that on the DVD set Drumset Technique/History of the U.S Beat. So here I’m taking that melody and performing it in a different way. And that ties in to the fact that I learned how to play all the Journey songs open-handed. Right-hand lead, or left-hand lead. One of the reasons I wanted that option is because I didn’t want to play backbeats with my left hand all night. It gives my left hand a break so it could play 8th notes on the ride cymbal or hi-hat. And it gives me more orchestrational ideas.

I started to play more open-handed when I played with Hiromi, out of the necessity of learning Simon Phillips’ drum parts. So on “Interdependence” I play the left-hand jazz beat on the hi-hat and the cymbal and play all the melodies with my right hand and right foot. And one of the ways I developed the open-handed playing was going back to the basics, the Jim Chapin book or Syncopation, and playing the ride cymbal beat and playing the figures with my right hand. I’m not completely ambidextrous at this point for jazz, but for the Journey music I can do it.

Going Through the Motions

MD: Your DVD/book package Pathways of Motion looks at four different matched-grip styles. Was the impetus left-thumb injury or musical curiosity?

Steve: It did start because I was having some problems with the CMC joint, at the base of the thumb on my left hand. So I decided to do a few things to remedy that, including altering my traditional-grip technique, which Jojo Mayer helped me with. He told me to open up my fingers more. I was playing more with the first [pointer] finger over the stick most of the time. He said if you release that finger and grip more with the thumb, then you won’t have that tension. But that takes some reeducating to be open and not afraid you’re going to drop the stick, which I do sometimes. [laughs] Advertisement

But the other thing is just that I wanted to play more matched grip, and I realized how limited my left hand was in the matched-grip position. In front of a mirror, I started to examine the motions of my right hand, because my right hand feels very fluid, and I could start to see that I was using a lot of different grips with the right hand. It was one way on the cymbal, another way on the tom, a different way on the snare drum. So I mirror-imaged that with the left hand. And the easiest way to do that is to play something in unison and really examine the motions and the pathways that the sticks are going through space. I realized I was using essentially four grips. And that led me to spending time with each grip.

MD: Describe each one, please.

Steve: Grip 1 is the basic, German grip, with the palm down and the hand over the stick. Grip 2 is the idea of the resonating chamber, where the stick is down more in the first joint of the fingers. Grip 3 is the French grip with the thumbs up. And Grip 4 is the “Tony Williams” grip, which I’ve been using for a long time. That’s almost like if you played a taiko drum and you’re just holding the stick with the back two fingers, like the way I saw Tony Williams play matched grip. With that, it’s very easy to get a big sound because of the range of motion.

MD: But that one’s hairy in terms of dropping the stick, right?

Steve: It’s more the transition between grips. As much time as I spend with the grips, the key to using all four is the transition from one to the other. I’ll go from 1 to 4, or 2 to 3, and in making that transition is somewhere where I’ll lose the stick. The French grip is the one that’s the least secure for me, not the Tony one. So focusing on those, I was getting more control and more technique with my left hand. It’s still not as good as my left-hand traditional grip, so when I really need to play something that’s challenging, I’ll go back to traditional grip. Advertisement

MD: Well, it’s been fifty years of that one for you.

Steve: Exactly. And when I started to talk to Rob Wallis about doing some demos, he said, “This is great—why don’t we document it?” And the more I thought about it, most of the technique videos are by traditional-grip players, whether it’s Dave Weckl or Jojo Mayer or Tommy Igoe. So there are a lot of matched-grip players, but no one is addressing the details of what matched grip is. And my observations felt like they could be helpful. We got into it and made it into a DVD and a book. A lot of drummers make these changes naturally but are not conscious of it. They’ll have what I call the “nonsymmetrical” grip. They’re playing French on the ride cymbal and German on the snare.

MD: What about someone like, say, Jon Fishman from Phish? I see him playing French on the outside to the right of the bell on his ride, but he’ll play German when bringing his right hand to the hi-hat. Isn’t that weird?

Steve: No, not weird at all. Playing traditional grip is playing a nonsymmetrical grip. And that’s a very natural grip to do. If you want a lighter sound on the cymbal, you can use the French grip. German grip for a heavier sound. Advertisement

Leading, and Following

MD: Dave Weckl told MD how difficult it is to keep a working group on the road, and how he had to take on more sideman work. Is there a bright future for leading jazz groups like Vital Information?

Steve: I’m in a similar position that Dave’s in, where it is hard to keep a band working. And one reason is because we’re drummers, and drummer-bandleaders have a smaller piece of the market. One of the classic examples is that of Buddy Rich and Frank Sinatra. They were roommates when they played with Tommy Dorsey. One of them ended up playing gigs and probably dying broke, and the other became a superstar. One was a singer and one was a drummer. They were equally talented. That’s the life of a drummer.

I do the touring when I can and as much as I can, but it’s not enough to make a living from. And it is expensive, so sometimes I break even or even lose money. The goal is that we all get paid decently enough to do the gig, and have fun and bring the music to people. So I’ll continue to do it. But I’ll still go out and play with Mike Stern, and Zakir called me for a gig but I’ll be out with Journey. But those calls will keep happening, I hope, especially once I get back full time into my jazz and sideman career.

MD: Speaking of sideman jazz, talk about the Hiromi gig. That’s complicated music.

Steve: Learning her music is intimidating and very difficult and takes a long time. I subbed for Simon Phillips for about three years. I learned her first three Trio Project albums. It’s some of the hardest music I’ve ever played but some of the most fun I’ve ever had on stage. The music is incredibly rewarding and pushed my musicianship to a new level. The drum chair in Hiromi’s trio is a chair of support, but also you’re the second soloist. There was a drum solo in almost every song, and most of them in some odd time. Advertisement

And learning Simon’s parts was a pleasure, because he did a really fantastic job orchestrating her music. She writes her music very clearly by hand. They’re not computer charts. Some of the charts are literally ten pages long. And she and Anthony [Jackson, bass] are great to be on tour with. So it was peak experience for me. And now Simon isn’t with Toto, so he plays all of the gigs.

The Live Experience

MD: Anything you do to keep your chops up while on the road?

Steve: I pulled out the Wilcoxon book that I had when I was a kid. I’ve been going through that, first of all just to read music and to work on some of those versions of how to use the rudiments in swinging ways. And I still practice Konnakol on a daily basis. I also recently brought my brushes out, which I practice backstage. I’d missed it. It felt good. It was therapeutic just to play brushes. I needed it for balance.

MD: Do you have a perspective on the technological advances today and how they’ve shaped the drumming landscape?

Steve: It does seem as though people are using YouTube a lot to get information, inspiration, ideas, drumming concepts. But nothing will substitute being in the room with a drummer. And I see videos that are impressive when the drummers are playing by themselves or playing with a track. Can they play with live musicians? And young drummers are playing very loud, in general. With headphones or to tracks. But if you adjust their playing to a room with a piano player over there and a bass player over here, they can’t do it, because they can’t control their dynamics, and without the click their time is not really there. So the idea of playing for the room is a foreign concept. As much as many young drummers are becoming technically good, without the experience of playing with live musicians, it’s going to be difficult to bridge that gap of becoming musicians who have a lot of options available. Advertisement

MD: Does Journey have a finite end time for you?

Steve: The original agreement was for two years, 2016 and 2017. And we’re talking about me doing a third year.

MD: Well, they’re not going to stop. We know this.

Steve: [laughs] No, looks like they’re going to keep going. So we’re talking about it, and it’s possible that I’ll do the third year. And in some ways I feel like I have a shelf life as a rock drummer. And one of the reasons I decided to play with Journey now is that I’d better do it while I’m physically able to do it. It’s hard work and I have to do a lot of pre-show warm-up and after-show yoga and stretching and warm down.

I’m using good technique and I’m not denting heads or breaking sticks or cymbals, but it’s still hard work to play ninety minutes or even two hours sometimes. And I don’t want to go on so long that I hurt myself. I want to be viable for the rest of my career. Like Roy Haynes and some of my heroes, I want to play up until the end. There are a lot of great players still out there doing it into their sixties, seventies, and eighties.

Drums: Sonor SQ2 in white lacquer finish with black lacquer inside and black chrome hardware

• 5.5×14 Steve Smith Signature metal snare

• 5.75×14 snare (detuned)

• 5×12 snare

• 7×8 tom

• 8×10 tom

• 9×12 tom

• 14×14 floor tom

• 16×16 floor tom

• 16×18 floor tom

• 14×22 bass drum

Advertisement

Notes

• 5.75×14 snare features vintage beech shells and modern hardware

• Bass drums feature vintage beech shells with modern bearing edges

• 5×12 snare and all toms feature medium maple shells

• Custom-made sub-kicks made by Russ Miller using Sonor shells (one in front of each bass drum and one under 18″ floor tom)

Hardware: Sonor 6000 and 4000 series, two DW 5000 Titanium single pedals with nylon straps, Porter & Davies throne

Cymbals: Zildjian

• 18″ Avedis crash (1,302 grams)

• 15″ Avedis hi-hats (1,128-gram top cymbal, 1,424-gram bottom)

• 22″ Avedis ride with three rivets (2,536 grams)

• 10″ Flash splash

• 22″ Avedis ride (2,626 grams)

• 19″ Avedis crash (1,538 grams)

• 19″ Avedis crash (1,576 grams)

• 34″ gong

Heads: Remo. Main snare batter: Fyberskin Diplomat. Auxiliary snare batters: Coated Ambassador. Tom batters: Clear Ambassador. Bass drum batters: Clear Powerstroke 3 with black dots. Bass drum resonants: Clear Powerstroke 3 with no hole. (Felt strip muffling on bass drum batters and resonants, installed about 3″ from the top of the drums.) Advertisement

Sticks: Vic Firth Steve Smith Signature model

Accessories: Cympad Optimizers on all cymbal stands (Ride model on bottom, White on top), Sensaphonics 3D Active Ambient in-ear monitor system, Shure SM91 mics mounted inside each bass drum with Kelly SHU Flatz bass drum mic mounting system.