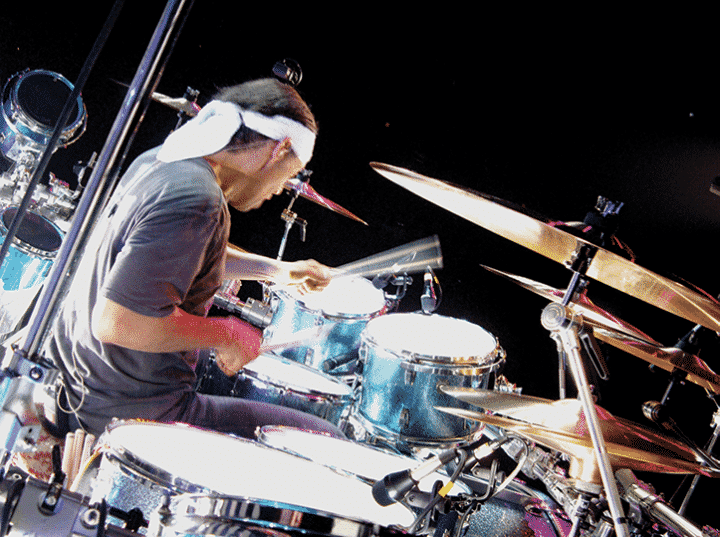

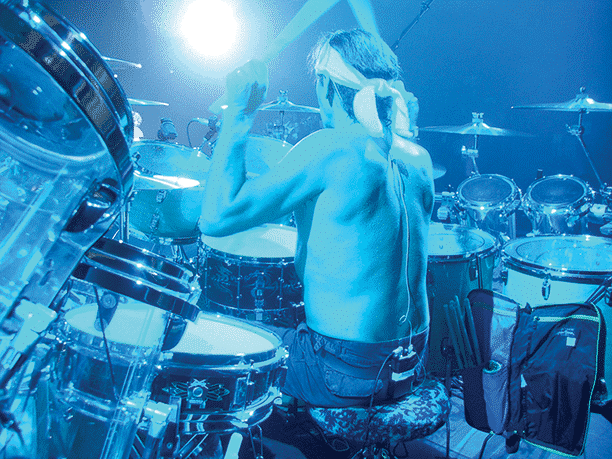

Van Halen’s Alex Van Halen

For over forty-five years, Alex Van Halen’s brilliant, forceful, grooving, and melodic drumming has been the driving force behind one of the truly great rock bands that ever existed. His bash has graced so many classic Van Halen radio staples, like the bruising “Runnin’ with the Devil” or the freight train double bass boogie “Hot for Teacher.”

Those hits spoke loudly to the devil-horn-flashing masses, but it was always through the deeper album cuts where true Alex disciples connected. Tracks like the up-tempo “Light Up the Sky” (from 1979’s Van Halen II) and the funky “Spanked” (from 1991’s For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge) showed the wide range of drumming approaches the drummer had in him.

The band may have had a hard time avoiding the tabloids, but on record and in concert, they were a multifaceted beast able to execute a variety of styles, and Alex Van Halen, along with his perma-smiled, genius brother, was the catalyst from the very beginning. He will forever be linked to a certain go-for-it way of playing, a swinging feel that few brought to hard rock, and an evolving drum tuning that was often imitated but never accurately duplicated. Advertisement

“One thing we won’t do is lie to the audience,” says Van Halen. “We put everything into it.” Looking back on his influences and contemplating the state of modern music, Alex offers an introspective reflection on how he came to develop his one-of-a-kind drumming voice and its role in the band that bears his name. [At press time, Modern Drummer learned of the passing of Edward Van Halen. This interview was done prior to that.]

MD: Your early life has been somewhat documented, but now after a long career, are you able to better appreciate how your musical upbringing informed your drumming in Van Halen?

Alex: I learned music by hanging out. I was there 25/7. My brother and I were everywhere, exchanging ideas. We were watching what we liked, what we didn’t like. Music isn’t something you learn in the classroom and then practice in the closet and then go out and do it. Music is about people. That’s what my father taught me. I played tenor saxophone and Ed played piano for twenty years. But our dad was unbelievable. He didn’t get the recognition or have an opportunity to make records, so it’s a shame. But he was so phenomenal. It was embarrassing to play in front of him because we could never be as good as that.

MD: So, a love for jazz eventually turned into a love for rock.

“Music isn’t something you learn

in the classroom and then practice

in the closet and then go out and do it. Music is about people.”

Alex: We started off with the Dave Clark Five and the Rolling Stones and Herman’s Hermits. But when the Beatles came out with Sgt. Pepper’s, we couldn’t play any of it. It had too many layers. That was a turning point for me and Ed. Advertisement

MD: How would you arrange material in rehearsals or in the studio? Would you contribute as you saw fit?

Alex: All Ed and I did was play, and he would know if I wasn’t enthusiastic about something and wouldn’t play it with full conviction. It’s kind of an unspoken deal. There were some songs that Ed had in his head that he wanted to hear a certain way. And being part of a unit, I owe him that. I’m not out here to compete with anybody or put my name on it; I’m here to work for the song. And if this is what you hear, Ed, then I will do that. But there were other days when I’d say, “I hear it this way.” [laughs] But remember, Ed and I grew up in the same 800-square-foot house, and we listened to the same shit. So, we were exposed to the same stuff, and we thought very similarly.

MD: And back in the day, it sounds like it all came together so quickly, making those classic Van Halen records.

Alex: We’d been in a number of different studios before we made our first record. And it’s like all the engineers went to the same school. And what qualifies as a technically great recording—the signal to noise ratio, and this and that—it’s garbage. Put a fucking microphone up! That’s why grunge was so great. When Nirvana came out, it was just a couple of mics, or at least they made it sound like that. That’s the way it should be. I talk to Taylor [Hawkins] all the time, who lives down the street, and we have a laugh at how stupid the approach to miking drums is. And he’s right. It’s not the way to do it. In the old days, with Led Zeppelin, the room is what gives you the space, the decay. The sound of the drums is not really in the drums, it’s in the decay. You’re looking in the wrong closet, buddy! We don’t dig what you’re doing. It’s not us. So, by the sixth record, we recorded in Ed’s studio. And to us, the process was just as important as the outcome. We would lock ourselves in the studio for a year to see what would come out. That was the attitude.

MD: Let’s discuss your mechanics a bit. Going by different parts of the kit…who was your main influence regarding bass drum?

Alex: The main guiding light was Ginger Baker. He was a fucking poet, and most people don’t have any idea of what the hell he was playing, how complex his playing was, mainly during his solos. During the songs it was a different scenario. Ginger and I were sort of friends. I had time to hang with him a bit. He was incredible. Drugs got in the way here and there, but by and large he was true to his art. But he left an imprint on us. It’s one thing to be inspiring, but a tennis player can inspire a drummer. It has nothing to do with the notes. Miles Davis said any motherfucker can play the notes. It’s the attitude. It’s the delivery. Advertisement

MD: What about ride cymbal?

Alex: When we first started, it was a curse to say you came from a jazz background. Now I think the musical community is a little more open to different ideas. But we started in jazz. Ed and I were making a living playing music when we were barely in our teens. And you watch other people play and you see what you like and what you don’t like. It’s not a complicated process, but it’s a lengthy one.

When something feels right, then you’re drawn to it. Those Eastern, Tibetan bells and things, different tones cause different things in your body, whether people are aware of it or not. Certain frequencies drive me up the wall. But your instrument is something hopefully you have control over, and then you can put in the frequencies that you like. And early on, I was drawn to Paiste because they sounded phenomenal, especially in the context that we play. But my taste was being able to hear the bell, so you had clarity, with some splash afterwards.

MD: Toms?

Alex: Again, Ginger Baker was the guy. There were probably a thousand guys who did the same thing, but Ginger was the one who ended up on the record and the one I ended up listening to. He had a very distinct tone on each drum; it wasn’t a thud from one to the other. And Hal Blaine because his records were on the radio, and from the radio is where you learn. That’s what you grow up on. He had some great sounds. Advertisement

MD: Your snare tone is very distinct as well. The tuning, the taping…

Alex: The snare is your instrument; it should be your identity. Some of it is the choice of drumheads and the microphone and the room you record in, but mainly you play until you get it right, for yourself, to your own taste. And you’ll know that when it resonates with your being, if you will.

There are times when we’re in the studio, and it just doesn’t happen. Ed and I are very aware of the lineage and what influenced you. Andy Johns was producing For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge, and he of course [engineered] the fourth Led Zeppelin record. And we really liked the sounds on that. You don’t try to duplicate or imitate or emulate, but it’s inspirational. And you have the guy who did it, so let’s see what you can come up with. And Ed, Andy, and I were in the studio, twenty-four hours a day, having a laugh and telling stories. It was great. This is what music is about. It goes across generations and cultural lines. And I’m thinking, you’re the guy who recorded “When the Levee Breaks,” so you should know what sounds good. But after four months, we weren’t getting any sound at all. And I was like, “Andy, with all due respect, what the fuck are you doing?” [laughs] And he looks at me and says, “Oh, Alex, I’m so sorry. I just forgot. I don’t remember.” [laughs] But we got stuff down. Andy did the work.

MD: Players of your vintage had a unique, personal character that was linked to them. No one really sounded like you or the band on rock radio. Now technology seems to be homogenizing everything to be perfect and sometimes soulless. What are you hearing today? Advertisement

Alex: Technology is the death of humanity. But once in a while, the humanity of what we do sticks its head out and people say, “Yeah!” because they relate to it. You couldn’t stop Foo Fighters, because they just went out and played, because it was natural, and it was rock ’n’ roll. It was energized, and it was everything you get into this line of work for. And the day you stop feeling it is the day maybe you should do something else. But there’s a natural course of events where you have to taper it a little bit or you’re not going to make it to the end. We did two and half hours in 2007 and two hours fifteen in 2015. So, we still did a lengthy clip. How Paul McCartney does it? I’ll never know.

MD: Sounds like you’re still inspired musically. It still moves you.

Alex: Music is a language, and if you’re speaking Russian, only Russian people will listen to you talk. If you’re playing progressive music, only progressive music people will listen to you talk. I’m more of a Zeppelin, AC/DC, Beatles kind of guy. I love the melodic stuff. I love the energy. I love that you’re actually touching human emotions. When the music became technical, the stuff in 5/4, the emotion came out of it, don’t you think? And Ed and I were big fans of a band like U.K. That’s where the Rototoms came from. It was a very refreshing sound. But for my personal taste, I’d rather hear James Brown. And that’s ultimately what music is about. You take different ingredients, you stir them together, and you see what happens.

Story by Ilya Stemkovsky

Photos by John Douglas