Marky Ramone: Punk Legend

by Michael Dawson

photo by Paul La Raia

Although he’s not the only drummer to have adopted the Ramone surname—Tommy was the group’s original drummer and Richie took over for a period in the mid-’80s—Marky Ramone held the longest tenure with the legendary punk pioneers, appearing on eight studio albums and several live discs, while also globetrotting with the band up until their final show on August 7, 1997.

In recent years, Marky’s been a catalyst behind various Ramones compilation CDs as well as the documentary DVD Raw, which was created from the drummer’s personal camcorder footage. Marky has also appeared on several records as a sideman and as a leader, and he’s traveled around the world speaking about his experience as a member of one of America’s greatest rock bands.

Before he became known as the relentless rhythmic force behind the Ramones, Marky (born Marc Bell) was a prominent figure on New York City’s underground rock scene. His first gig, the power-rock trio Dust, raised some eyebrows in the early ’70s with their Brit-inspired heavy metal sound. Then the young drummer teamed up with punk icon Richard Hell (of Television fame) to form the Voidoids in 1977. Marky stayed with Hell for a year before beginning a fifteen-year run with the Ramones. Advertisement

We sat with Marky on a rainy New York afternoon in 2007—immediately after he completed a two-hour taping of his weekly Sirius Satellite radio show, Punk Rock Blitzkrieg—to take a look back at some of the highlights of his discography.

Dust, Dust (1971)

The drumming on the Dust stuff is totally opposite from what the Ramones was all about. It’s busier, there were more fills, and there aren’t any 8th notes on the hi-hat, floor tom, or ride cymbal. It was basically quarter-note playing.

Dust was my first album, and I was about sixteen years old. I think the album’s great because it has a lot of energy. I used a Rogers drumset, and it took me about four days to do the basic tracks.

The beat on the opening tune, “Stone Woman,” has a groove/soul kind of feel. I’ve always liked soul drummers, so I applied their feel to that song.

Dust, Hard Attack (1972)

This album has a really good drum sound. From our advance, I was able to buy an over-sized Ludwig set. So that’s why the drumming is a lot heavier. I’m doing a lot of crossover triplets, double-stroke rolls, and a lot of different accents. Advertisement

There’s also a lot of Keith Moon influence on Hard Attack. He was great because he had his own style, and not because he was a technician. When you get too technical, you sound like everybody else. I eventually got into all of the other guys, like Mitch Mitchell, Ginger Baker, Clive Bunker from Jethro Tull, Hal Blaine from the Wrecking Crew—all of these great players. I took their influences and mixed it up.

Richard Hell & the Voidoids, Blank Generation (1977)

After Dust, I did a blues record with Johnny Shines. He was good friends with Muddy Waters and B.B. King, a genuine blues guy. That record was all 6/8 beats.

The next thing I did was Blank Generation. I knew Richard from hanging out at CBGBs. There’s a lot of jazz influence on this record. For instance, “Blank Generation” has a swing 4/4 beat. This type of playing comes from guys like Joe Morello with Dave Brubeck, and Mitch Mitchell, who was really a jazz drummer.

“Liars Beware” is close to the same speed as some Ramones songs, but I wasn’t playing 8th notes yet. I was still into heavy-handed quarter-note arm playing. And I used a Ludwig Vistalite set for that album. Advertisement

The Ramones, Road to Ruin (1978)

I got into the Ramones because I was hanging out at CBGBs in New York. Tommy Ramone wanted to produce after being in the band for three and a half years, and I wanted to move on from Richard Hell. Dee Dee Ramone was a friend of mine, and he asked me if I wanted to join the Ramones. We arranged an audition, but I knew that I was going to get it. I was in the New York scene, and they knew me. They would come see Dust before the Ramones even existed.

After I joined, the guys gave me twenty-eight songs to learn in two and a half weeks for a show. Then I had to learn and record fifteen or sixteen studio tracks for Road to Ruin. I just studied day and night.

The Ramones were all about straight 8th-note playing. Johnny and Dee Dee played constant down-stroke 8th notes. So that’s what was required of the drumming. I had to learn how to play 8th notes on the hi-hat, ride cymbal, and floor tom, and keep it going for an hour and twenty minutes. And believe me, it isn’t easy. To conserve energy, I don’t use any part of my body that I don’t have to. I just find a groove and keep focused. I’m not one of those players that has to use big arm motions. I use mainly fingers and wrists. Advertisement

The first song I recorded with the Ramones was “I Want To Be Sedated.” I used a white over-sized Rogers drumset with a 6½” Slingerland chrome-over-wood snare. I had the bottom heads off of the toms, and the mics were inside the drums. I used Remo black dots on the toms and bass drum, and I put tape with tissue underneath it to deaden the sound a little. On the circumference of the bass drum, I put 2″ foam against the batter side, which defined the sound really well. The snare had a Remo Emperor with no muffling, and I always played rimshots.

This was also when I started to use Paiste cymbals. You can hear the difference between the cymbals on the first cut, “I Just Want To Have Something To Do.” On the hi-hat side I used a Zildjian, and on the ride-cymbal side I used a Paiste. The Paiste is the one that sounds like broken glass.

It took me two days to do the drum tracks. We all played together, just in case we got a perfect track. That didn’t happen, but if we got a good drum track, the other guys could overdub their parts. At the most, we did three takes of each song. Advertisement

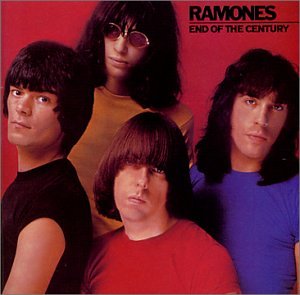

The Ramones, End of the Century (1980)

Phil Spector liked the Ramones. He thought we had the ingredients of bands like the Beach Boys, the Ronettes, Jan & Dean—stuff that he produced in the ’60s—but with Marshall amps and heavy drumming. He wanted to produce us, and we were all happy to work with him.

It took me about a week to do all of the tracks. But it took four or five months to make the album because of the overdubs, the mixing, and the additional strings, horns, and percussion parts. It ended up being our best-selling individual album.

On some of the softer songs, like “I Can’t Make it On Time” and “I’m Affected,” I used a towel on the snare drum, which is an old recording trick. I also brought in some RotoToms, which I used to get a certain sound off of the echo chambers in the studio. They’re on “I’m Affected” and “This Ain’t Havana.” Advertisement

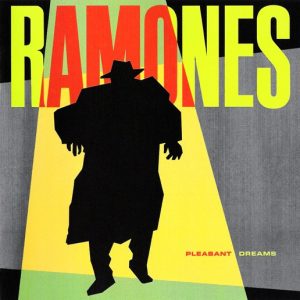

The Ramones, Pleasant Dreams (1981)

Graham Gouldman was brought in to produce this one. He was responsible for a lot of the English Invasion songs of the ’60s. I liked his production. And I love this album.

At this point, I had a sponsorship with Tama. So I used a set on this album, with a Rogers Dynasonic snare. I also used some kettle drums on “This Business Is Killing Me.” It took me two or three days to do the basic tracks.

“It’s Not My Place” has an early rock ’n’ roll Bo Diddley–type of groove during the verse. It was different from what the Ramones would usually do, but it matched the ’50s feel of the song.

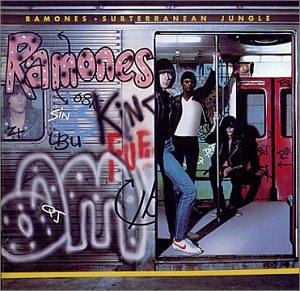

The Ramones, Subterranean Jungle (1982)

The songs on this album are good, but I hated the production. Richie Cordell got this ridiculous drum sound, almost like a drum machine. And the snare drum was tuned really low, which gave it a papery sound. That sound was popular because new wave and dance music was coming in. A lot of bands were going electronic and experimenting. But I didn’t want to experiment. I like natural acoustic-sounding drums with no bullshit to them. Advertisement

To this day, I make sure that I get the sound that I want. The producer is the producer, but you’ve got to watch out for yourself, too. You have to have some kind of consistent sound so that people know it’s you. It’s your sound. You might not always achieve it, but always try.

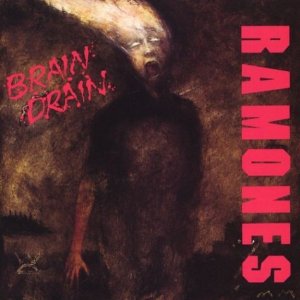

The Ramones, Brain Drain (1989)

After we made Subterranean Jungle, I was asked to leave the band. I wasn’t into drugs, but I was a periodic drinker. And when I drank, a lot of strange things happened. And that was affecting the attitude of the band. So I had to go away for a while to learn that it’s more important to continue my musical career than it is to drink. I did various odd jobs, like putting up wrought iron gates on crack houses. But at the same time, I was still making money from Ramones merchandise and record sales because I was still a part of the corporation. I did that for three years to get back in touch with reality.

My replacement, Richie, eventually quit the band because he wasn’t collecting money on merchandise—while I was. And I don’t blame him. But they had eighteen shows booked that they couldn’t get out of. They tried to use Clem Burke from Blondie, but he only lasted for two shows. So Johnny, the guitarist, was thinking about retiring. Then Joey told him that he saw me at a club in New York and that I’d been sober for four years. And he thought that they should get me back. But when I came back, everything was the same. They were still crazy people. But if they weren’t crazy, they might not have made that kind of music. Advertisement

The first song that I did when I rejoined was “Pet Sematary,” for the Stephen King movie. We did the album with Bill Laswell producing. He had worked with Iggy Pop and many other bands, like Motörhead. He had me play facing a brick wall. I had no contact with him or the band except through the headphones. The drums sounded good, but they’re way too far upfront.

But this was a good comeback album. And there are elements of hardcore punk in there. A lot of punk bands wanted to play faster than us, so they dropped the 8th notes in the ride. But it’s much easier to play quarter notes with that polka-punk beat than it is to play like we did. We did songs like “Ignorance Is Bliss” to prove to all the young bands that we could do hardcore, too.

The Ramones, Loco Live (1991)

This album was recorded live in Spain to about 12,000 people. It’s the fastest we ever played. We were playing so much that it was getting easier and easier to play, so we didn’t think about the tempos getting faster. But I do feel that the speed interfered with the original intent of the groove; it was too fast. But a lot of kids love it because of the energy. Advertisement

The Ramones, Mondo Bizarro (1992)

That was one of the best Ramones albums. I was sponsored by Pearl at that time, so I used one of their blue birch sets with my Rogers snare drum. I used Remo Emperor heads with the bottom heads still on the toms.

I was able to do a lot of good drum fills on this one. Ed Stasium, the engineer from Road to Ruin, was producing. I was very happy about that because I knew he was going to get a great drum sound. I told Ed to listen to the song “(I’m In With The) In Crowd” by Dobie Gray. That song had a great tom sound that I wanted to get. I told Ed to try to get as close to that as he could.

For the kick drum, I wasn’t using the foam muffling anymore. I just leaned a towel against the batter side with a square piece of duct tape on the front head, so it wouldn’t ring too much.

The Ramones, Acid Eaters (1993)

This was our acknowledgement to some of our favorite ’60s bands. I picked nine of the songs, and we had Pete Townshend [of the Who] sing vocals with Joey on “Substitute.”

This was around the time that Green Day, the Offspring, and Rancid came out. They paid homage to the Ramones and were very open about their influences. We were grateful for that. Bands like them kept this genre of music alive. Plus, the grunge movement was big at that time, and Nirvana were huge Ramones fans, as was Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam and the guys in Soundgarden. They gave us enthusiasm to continue for another three or four years. Advertisement

The Ramones, ¡Adios Amigos! (1995)

Daniel Rey’s production on this one is great. I used a silver sparkle Pearl maple set and a Ludwig Black Beauty snare drum. Between Ludwig and Rogers, you can’t go wrong. Older snares have a certain charm that I like. Maybe it’s because I grew up with them and I’m used to their sound. I’ve tried a lot of newer drums from different companies, but there are things that I’m looking for that they don’t have.

The Ramones, We’re Outta Here (1997)

This was our last show. After twenty-two years, it was time to end. You want to go out sounding good. You want fans’ memories of you to be intact. So that was the end of the Ramones.

The Misfits, Project 1950 (2003)

I got involved with the Misfits because I felt bad for their front man, Jerry Only. He had bought the rights to the band name and formed the third incarnation of the Misfits, but his band walked off on him. So I said I’d play for a while to help him out. It ended up lasting three and a half years. We only did this one album, which was ten ’50s songs. I picked about six of them. It was recorded at Schoolhouse Studios in Manhattan.

Marky Ramone, Start of the Century (2006)

I had a lot of songs written after the Ramones retired. The topics were different from what the Ramones would usually write about. But I wanted to do some records with my band the Intruders and put them in the Ramones bin. Unfortunately, the record companies that put out those two albums weren’t set up properly to promote them. Now I own the rights to both records, so I re-released them along with an eighteen-song set of Ramones songs that I did with some friends. Advertisement

Osaka Popstar

And the American Legends of Punk (2006)

The drum tracks for this album were also recorded at Schoolhouse Studios. I like my playing on it, and the songs are good. The record came out last year, and it’s been doing very well. The videos for “Wicked World” and “Insects” were picked up for the in-house programming at Hard Rock Café.